Succession to Elizabeth I facts for kids

When Elizabeth I became Queen in 1558, she had no children. This meant that who would rule England after her was a big question for over 40 years. When she died in 1603, the crown went to James VI of Scotland. Even though James became king easily, the question of who would succeed Elizabeth had been a huge topic for many years. Some historians even think it was a main reason behind many political events during her reign.

Elizabeth I didn't want to name her successor. She was worried that if she did, her own life might be in danger. She also wanted England to have a good relationship with Scotland. Scotland had many Catholics and Presbyterians who didn't like female rulers. Catholic women who would obey the Pope instead of English law were not wanted.

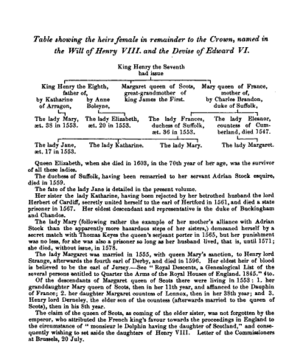

Henry VIII, Elizabeth's father, had made a will about who should inherit the throne. He named one boy and seven girls who were alive when he died in 1547. These were: (1) his son Edward VI, (2) Mary I, (3) Elizabeth I, (4) Jane Grey, (5) Katherine Grey, (6) Mary Grey, and (7) Margaret Clifford. Elizabeth outlived all of them.

The legal rules for who could inherit were complicated. They involved old laws and Henry VIII's will. Different people had different ideas about what these rules meant. Later in Elizabeth's reign, during the war with Spain, political, religious, and military issues became more important in the succession debate.

Contents

Who Could Inherit from Henry VII?

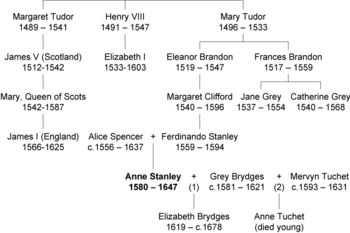

The main question about who would be the next ruler came down to the two daughters of Henry VII who grew up: Margaret Tudor and Mary.

The Lennox Claim

Mary I of England died without getting her chosen successor, her cousin Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, approved by Parliament. Margaret Douglas was a daughter of Margaret Tudor. She lived until 1578 but became less important in the talks about Elizabeth's successor. Elizabeth never made it clear who should inherit from the Tudor family. In 1565, Margaret Douglas's older son, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, married Mary, Queen of Scots. After this, the "Lennox claim" was seen as part of the "Stuart claim."

The Stuart Claimants

James VI was the son of two of Margaret Tudor's grandchildren. Arbella Stuart, another serious person who could become queen in the late 1500s, was the daughter of Margaret Douglas's younger son, Charles Stuart, 1st Earl of Lennox.

James VI's mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, was thought to be a likely successor to the English throne. Early in Elizabeth's reign, Mary sent people to England to try and get Parliament to choose her. Mary was a Roman Catholic. Her closeness to the throne caused many plots, making her a big problem for the English government. She was executed in 1587. In that year, her son James turned 21, while Arbella was only 12.

The Suffolk Claimants

| Hypothetical succession in the female line from Henry VII, through his daughter Mary and her second marriage |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While the Stuart family (James and Arbella) had political support, the descendants of Mary Tudor were also important by 1600. Legally, they could not be ignored. Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, and Eleanor Clifford, Countess of Cumberland, both had children who were in line for the throne. Frances and Eleanor were Mary Tudor's daughters from her second marriage to Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk. Frances married Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk. They had three daughters: Lady Jane Grey (1537–1554), Lady Catherine Grey (1540–1568), and Lady Mary Grey (1545–1578). The two youngest lived during Queen Elizabeth's reign.

Catherine's first marriage was canceled, and she had no children from it. She secretly married Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford in 1560. They were both put in the Tower of London after Catherine became pregnant. They had two sons, but the Church of England said both were illegitimate (not born within a legal marriage). After Catherine died in 1568, Seymour was released. The older boy became Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp. The younger was named Thomas. The "Beauchamp claim" was pushed more by Thomas. He tried to prove his legitimacy, which his older brother could not. He died in 1600. Even after Elizabeth's death, people still remembered the Beauchamp claim.

Lady Mary Grey married Thomas Keyes without the Queen's permission. She had no sons and was not interested in becoming queen.

Eleanor Clifford's family was often discussed for the succession. Her daughter Margaret Stanley, Countess of Derby had two sons, Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby and William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby. When Margaret Stanley was considered a possible queen, she was usually called "Margaret Strange." This was her husband's title. Her Catholic supporters later switched to the Stuart claim. Before he died in 1593, her husband Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby's claim was supported by Sir William Stanley and William Allen.

Ferdinando's place in the succession led to him being approached in the Hesketh plot in September 1593. This was a small plot to take power. His daughter Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven, was also part of the legal talks about who would inherit the throne.

The Yorkist Claim

Early in Queen Elizabeth's reign, some people were interested in a claimant from the House of York. Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, could only claim the throne by saying that Henry VII was not a true king. But he had some supporters, even ahead of the Tudor, Stuart, and Suffolk lines. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, a survivor of the Plantagenet family, was his great-grandmother. Her grandfather was Richard, Duke of York. A Spanish diplomat, Álvaro de la Quadra, thought that Robert Dudley, Hastings's brother-in-law, was trying to get the Queen to name Hastings as her successor in March 1560. There were also some claims from his relatives in the Pole family.

The Lancastrian Claim through John of Gaunt

A big political issue from the time of Richard II of England was brought up again. This was the idea that Richard's uncle, John of Gaunt, might claim the throne. This would go against the rule of primogeniture (where the oldest child inherits). Seven generations later, one of John of Gaunt's descendants was the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. Her claim was seriously put forward by Catholics. One reason given for Essex's Rebellion was that the Infanta's claim was gaining support with Elizabeth and her advisors.

The Succession Act of 1543

The Succession to the Crown Act 1543 was the third such law made by Henry VIII. It supported the rules in Henry's last will about who would inherit the throne after Elizabeth's death. This law meant that Lady Catherine Grey, who was Protestant and born in England, had a stronger claim than Mary, Queen of Scots. It also put the Stuart claimants at a disadvantage compared to the Suffolk claimants, even though James VI was descended from Henry VII's older daughter.

If Henry VIII's will had been ignored, it would have made things harder for James VI. It would have opened up new legal problems. The will specifically preferred descendants of Mary Tudor over Margaret Tudor. Without this Act, the succession could not have been handled under written law. If it was left to common law, the question of how James, a foreigner, could inherit would have been a more serious issue.

Elizabeth did not pass a similar Act of Parliament during her reign. She did not follow her father's example of allowing Parliament to discuss the succession. Instead, she actively tried to stop any debate about it. Paul Wentworth openly challenged her on this in the House of Commons in 1566.

In 1563, William Cecil wrote a bill that would give the Privy Council (the Queen's advisors) a lot of power if the Queen died without an heir. But he never put it forward. Parliament asked the Queen to name her successor, but she refused. A bill was passed by Parliament in 1572, but the Queen did not approve it. In the early 1590s, Peter Wentworth tried to bring up the question again, but the discussion was quickly shut down. The topic mainly appeared in plays.

Succession Writings

Discussion about who would succeed the Queen was strongly discouraged and became dangerous. However, it was not completely stopped. In the last 20 years of the century, the Privy Council worked hard against pamphlets and private writings on the topic. John Stubbs, who wrote about the Queen's marriage, avoided execution in 1579. But his hand was cut off, and he was in the Tower of London until 1581. In that year, Parliament passed a law against "Seditious Words and Rumours" against the Queen. Publishing books that were considered rebellious became a serious crime.

Because of this, much of the writing was anonymous (without a known author). It was passed around in handwritten form or, for Catholic arguments, smuggled into the country. Some was published in Scotland. For example, Leicester's Commonwealth (1584) was an illegal writing that attacked the Queen's favorite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. It spent a lot of its pages arguing for the succession rights of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Many essays, or "succession tracts," were passed around. From a large number of writings on the topic, a 19th-century librarian, Edward Edwards, chose five that were very important. The one by Hales showed a Puritan view. It largely set the terms for later debates. The other four argued for Catholic successors.

The Hales Tract

John Hales wrote a speech for the House of Commons in 1563. He supported the Earl of Hertford, because of Hertford's wife, the former Lady Catherine Grey. This was connected to the efforts of Lord John Grey, Lady Catherine Grey's uncle. He tried to argue that she was the royal heir early in Elizabeth's reign, which made the Queen very angry. This writing used an old law called De natis ultra mare. It was important in the later debate, but how the law was understood became key. It also caused a big uproar and claims of a plot. Hales only admitted that he had shown a draft to John Grey, William Fleetwood, and John Foster. Walter Haddon called Hales's arrest and the trouble that followed the Tempestas Halesiana (Halesian Storm). What Hales was doing was complex. He used legal arguments to rule out Scottish claimants. He also relied on research done abroad by Robert Beale to reopen the issue of the Hertford marriage. Francis Newdigate was involved in the investigation but was not imprisoned. Hales was. He spent a year in the Fleet Prison and the Tower of London. For the rest of his life, he was under house arrest.

The Case for a Catholic Successor

Early Writings

John Lesley wrote on behalf of Mary, Queen of Scots. His book, A defence of the honour of the right high, mightye and noble Princess Marie (1569), was stopped from being printed in London by Lord Burghley. It specifically pointed out the problems between the Succession Act of 1543 and Henry VIII's actual wills. Elizabeth would not accept Parliament having so much control over the succession. Further discussion of the succession was forbidden by law from 1571. A related work, thought to be by Thomas Morgan or Morgan Philipps, also for Mary, Queen of Scots, was another printing of Lesley's work in 1571. Lesley's arguments actually came from Edmund Plowden and had been simplified by Anthony Browne.

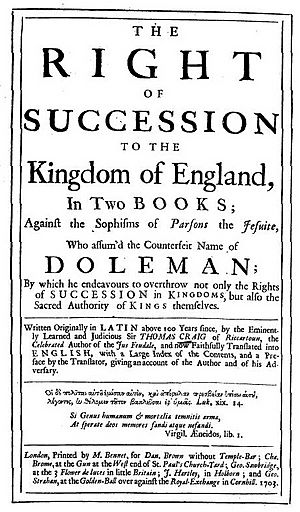

The Doleman Tract

The arguments naturally changed after Queen Mary's execution. It's interesting that Protestant supporters of James VI started using arguments that Mary's supporters had used before. And Catholics started using some arguments that Protestants had used.

A big step was taken in Robert Highington's Treatise on the Succession. This book supported the line through the House of Portugal. Robert Persons wrote a book under the fake name R. Doleman, called Conference about the next Succession to the Crown of England (1595). This book was against James VI's claim. It used Highington's arguments against those of Hales and Sir Nicholas Bacon. This book seemed to try to discuss all candidates fairly, including the Infanta of Spain, Isabella Clara Eugenia. Some people in England thought it meant that Elizabeth's death could lead to civil war. A part of the book suggested that Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex might have a big influence. This made Essex look bad to the Queen. It also tried to make Burghley look bad by suggesting he supported Arbella Stuart. It also cleverly dealt with the Lancaster/York issues.

Other Writings and Plays

The play Gorboduc (1561) has often been seen as a comment on the succession debate. This idea has led to much discussion. The play was performed for the Queen in 1562 and later published. Some argue it's a general "succession text" with themes of bad advice and civil war. From a literary point of view, it's important to know when the succession was a "live" public issue. This continued into the reign of James I. It also shows how plays might have commented on it. For example, Macbeth and King Lear, both about who should rule, were written early in James's reign.

The term "succession play" is now used for plays from that time that are about a royal succession. Plays like Shakespeare's Hamlet, Henry V, A Midsummer Night's Dream (through its hidden meanings), and Richard II are examples. Another later play that might be seen this way is Perkin Warbeck (1634) by John Ford.

The poet Michael Drayton hinted at the succession in his book Englands Heroicall Epistles (1597). This is now seen as a strong political statement. In the book, imaginary letters are exchanged between historical characters. Some see the work as a "family tree" leading up to the succession issue. It has a detailed discussion of the Yorkist claim in the notes for the letters between Margaret of Anjou and William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk.

The Situation at the End of the Century

Ideas about who would succeed the Queen had to be changed constantly from the late 1590s. There were many guesses, and the status of the people involved kept changing.

The Doleman tract from 1594 suggested one solution: the Suffolk claimant William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, should marry the Infanta of Spain and become king. However, Stanley married the next year. Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, who was Philip II of Spain's son-in-law, became a widower in 1597. Catholics suggested he might marry a female claimant, Lady Anne Stanley (the Earl's niece), or Arbella Stuart.

Thomas Wilson wrote in a report called The State of England, Anno Domini 1600 that there were 12 "competitors" for the throne. His count included two Stuarts (James and Arbella), three of the Suffolks (two Beauchamp claimants and the Earl of Derby), and George Hastings, 4th Earl of Huntingdon. The other six were:

- Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland (through John of Gaunt)

- Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland (through Edmund Crouchback)

- António, Prior of Crato, nephew of Henry, King of Portugal (through John of Gaunt)

- Ranuccio I Farnese, Duke of Parma

- Philip III of Spain

- The Infanta of Spain.

These six may have all been considered Catholic candidates. Wilson was working on intelligence for Lord Buckhurst and Sir Robert Cecil around 1601.

Of these supposed claimants, Thomas Seymour and Charles Neville died in 1600. None of the claims from Spain or Portugal came to anything. The Duke of Parma was discussed in the same way as the Duke of Savoy, but he married in 1600. Arbella Stuart was cared for by Bess of Hardwick. Edward Seymour was cared for by Richard Knightley.

See also

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |