The Guardian of Education facts for kids

The Guardian of Education was the first successful magazine in Britain that focused on reviewing children's literature. It was edited by Sarah Trimmer, an important educator, children's author, and supporter of Sunday schools in the 1700s. The magazine was published from June 1802 to September 1806.

The magazine offered advice on raising children and looked at different ideas about education at the time. Sarah Trimmer even shared her own ideas on education after studying the main books of the day.

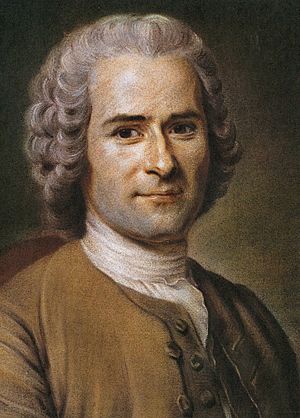

Trimmer was worried about the ideas from the French Revolution, especially those from the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. She strongly supported traditional Anglicanism (the Church of England) and wanted to keep the social and political order as it was. Even though she was quite traditional, she agreed with Rousseau and other modern educators on some things. For example, she thought that rote learning (learning by repeating things without understanding) was harmful and that fairy tales were not logical.

The Guardian of Education was the first magazine to seriously review children's books using clear rules. Trimmer's reviews were very thoughtful. They made publishers and authors change what they put in their books. The magazine also helped define what children's literature was and greatly affected how many children's books were sold. The Guardian also created the first history of children's literature, listing important books that scholars still use today.

Contents

Starting the Magazine

Sarah Trimmer decided to publish The Guardian of Education because many new children's books were appearing in the early 1800s. She was afraid these books might contain ideas from the French Revolution. The 1790s were a very wild time in Europe, with the French Revolution, calls for change in Britain, and wars. After these big changes, many people in Britain wanted to go back to more traditional ways, and The Guardian was part of this movement.

In her magazine, Trimmer spoke out against the Revolution and the thinkers she believed caused it, especially Jean-Jacques Rousseau. She thought there was a big secret plan by French revolutionaries, who did not believe in God and wanted democracy, to overthrow the governments of Europe. She believed these plotters were trying to ruin traditional society by "infecting the minds of the rising generation" through "Books of Education and Children's Books." Trimmer wanted to fight this plan by guiding parents to truly Christian books.

How the Magazine Was Organized

Each issue of Trimmer's Guardian had three main parts:

- 1) Parts from texts that Trimmer thought would teach her adult readers good lessons.

- 2) An essay written by Trimmer about education topics.

- 3) Reviews of children's books.

Trimmer wrote all the essays and reviews herself. The magazine did not always have the exact same sections. For example, starting in 1804, Trimmer began including an "Essay on Christian Education." In 1805, she sometimes reviewed "School books." She also started a tradition that continues today by dividing the books she reviewed by age group: "Examination of Books for Children" (for those under 14) and "Books for Young Persons" (for those between 14 and 21).

An expert on Trimmer, Matthew Grenby, thinks that between 1,500 and 3,500 copies of each Guardian issue were printed. This means its circulation was similar to other political magazines of the time. From June 1802 to January 1804, The Guardian came out every month. After that, it was published every three months until it stopped in September 1806. There were 28 issues in total.

Trimmer took on a big challenge by publishing her magazine. Grenby says she wanted to "assess the current state of educational policy and practice in Britain and to shape its future direction." To do this, she looked at the educational ideas of many thinkers, including Rousseau, John Locke, and Mary Wollstonecraft. In her "Essay on Christian Education," which was later published as a separate booklet, she suggested her own full plan for education.

How Books Were Reviewed

The Guardian of Education was the first magazine to take reviewing children's books seriously. Trimmer wrote over 400 reviews, which showed her clear rules for what made a good children's book. As a strong member of the Anglican Church, she wanted to protect Christianity from ideas that ignored religion or from other Christian groups like Methodism. Her reviews also showed she was a loyal supporter of the king or queen and against the French Revolution.

As Grenby explains, her first questions about any children's book were always: "Was it damaging to religion?" and "Was it damaging to political loyalty and the established social hierarchy?" Religion was Trimmer's top concern. She believed the Bible was completely true, not just in its message but also in its writing style. She wrote some of her harshest reviews against books that changed the Bible's style or content.

Grenby argues that Trimmer was not as strict a thinker as her reputation suggests. He points out that Trimmer, like Rousseau, believed children were naturally good. This idea went against old traditions, especially the Puritan belief in original sin. Even though she criticized Rousseau's works, Grenby says she agreed with his main idea that "children should not be forced to become adults too early." This meant they should not be exposed to political issues too soon.

Trimmer also believed that mothers and fathers should both share the responsibility of caring for the family. Like other modern educators and children's authors such as Maria Edgeworth, Trimmer was against rote learning. She supported flexible, conversational lessons that encouraged children to think for themselves. She also promoted breastfeeding (which was a debated topic at the time) and parents being involved in their children's education.

After studying her reviews, Grenby concluded that "Trimmer was... not nearly so harsh in her reviewing as her reputation suggests." Fewer than 50 of her reviews were mostly negative, and only 18 were truly harsh. These were easily outweighed by her positive reviews. She mainly objected to books that changed the Bible, like William Godwin's Bible Stories (1802). She also criticized books that promoted ideas she linked to the French Revolution or books that might scare children. She usually praised books that encouraged learning, such as Anna Barbauld's Lessons for Children (1778–79).

Fairy Tales

Trimmer is perhaps most known today for criticizing fairy tales, such as the different versions of Charles Perrault's Histoires ou Contes du Temps passé (1697). She disliked fairy tales because she felt they showed an illogical view of the world and suggested that people could succeed without working hard.

Trimmer's view of fairy tales, though often made fun of by modern critics, was common in the late 1700s. This was partly because most educators believed John Locke's idea that the mind was like a "blank slate" when a person was born. This meant the mind was very open to new ideas early in life. Trimmer was against fairy tales that were not based in reality and that would "excite an unregulated sensibility" in the reader. Without a clear moral lesson or a narrator to explain it, fairy tales could lead a reader astray. Most of all, she worried about children having feelings that were not guided or watched by adults.

One reason Trimmer thought fairy tales were dangerous was that they led child readers into a fantasy world where adults could not follow and control what they experienced. She was also shocked by the graphic pictures in some fairy tale collections. She complained that "little children, whose minds are susceptible of every impression... should not be allowed to see such scenes as Blue Beard hacking his wife's head off."

Fairy tales were often found in chapbooks, which were cheap, simple books. These chapbooks contained exciting stories like Jack the Giant Killer. Chapbooks were often read by poorer people, and Trimmer tried to separate children's literature from books she linked with the lower classes. Trimmer criticized the values in fairy tales, saying they promoted illogical thinking, superstition, and bad images of stepparents.

However, children's literature expert Nicholas Tucker argues that Trimmer was not just trying to censor fairy tales. He says that "by considering fairy tales as fair game for criticism rather than unthinking worship, Mrs Trimmer is at one with scholars today who have also written critically about the ideologies found in some individual stories." This means she was thinking critically about the messages in these stories, much like scholars do today.

French Revolution and Religion

Trimmer's ideas about the French philosophes (thinkers) were shaped by Abbé Barruel's book Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (1797–98). She copied large parts of this book into The Guardian itself. Her views were also influenced by her fears of the ongoing wars between France and Britain during the 1790s.

Trimmer stressed the importance of Christianity above all else in her writings. She believed that people should turn to God during difficult times. As children's literature expert M. Nancy Cutt explains, Trimmer and writers like her strongly believed that how happy a person was depended directly on how much they followed God's will. They disagreed with other thinkers who said that learning should focus on human reason and lead to a person's happiness in this life, which was guided by what was best for society. Trimmer and her supporters argued that French teaching ideas led to a country without morals, specifically to ideas that questioned God and led to revolution.

See also

In Spanish: The Guardian of Education para niños

In Spanish: The Guardian of Education para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |