Sarah Trimmer facts for kids

Sarah Trimmer (born Kirby; 6 January 1741 – 15 December 1810) was an important writer and critic of children's books in the 1700s. She also worked to improve education. Her magazine, The Guardian of Education, was the first to seriously review children's books. It also created the first history of children's literature, listing the most important early books. Trimmer's most popular children's book, Fabulous Histories, inspired many animal stories for kids and was printed for over 100 years.

Sarah Trimmer was also a very kind person who helped others. She started several Sunday schools and charity schools in her area. To help these schools, she wrote textbooks and guides for women who wanted to start their own schools. Her work encouraged other women, like Hannah More, to create Sunday school programs and write books for children and the poor.

Trimmer's books often supported the way society was organized at the time. As a strong Anglican Christian, she wanted to promote the Church of England. She taught young children and poor people about Christianity. Her writings explained the benefits of social classes, saying that everyone should stay in their God-given place. However, while she supported many traditional ideas, Trimmer also questioned some, especially about gender roles and families.

Contents

Early Life and Meeting Famous People

Sarah Trimmer was born on 6 January 1741 in Ipswich, England. Her father, Joshua Kirby, was a well-known artist. He even taught the Prince of Wales (who later became King George III) about art. Sarah had one younger brother, William. She was a better writer and sometimes wrote his school essays for him.

When she was young, Sarah went to Mrs. Justiner's boarding school. She always remembered this time happily. In 1755, her family moved to London. Because of her father's connections in the art world, Sarah met famous painters like William Hogarth and Thomas Gainsborough. She also met the famous writer Samuel Johnson. She impressed Johnson when she used her small copy of John Milton's Paradise Lost to help settle an argument. Johnson was so pleased that he invited her to his house and gave her a book. In 1759, her family moved to Kew. There, she met James Trimmer, and they married on 21 September 1762. After their wedding, they moved to Old Brentford.

Motherhood and Helping Others

Sarah Trimmer was very close to her parents. After she married, she walked to visit her father every day, later bringing her oldest children with her. She and her husband had 12 children in total—six boys and six girls. Trimmer was in charge of teaching her children. It was her role as a mother and teacher that first made her interested in education.

Inspired by Robert Raikes, Sarah Trimmer became very active in the Sunday school movement. She started the first Sunday school for poor children in Old Brentford in 1786. She and two local ministers, Charles Sturgess and Charles Coates, raised money. They set up several schools for the poor children in the area. At first, 500 boys and girls wanted to join Trimmer's Sunday school. Since they couldn't fit everyone, she decided not to accept children under five years old. She also limited each family to one student.

The parish set up three schools, each with about thirty students. One school was for older boys, one for younger boys, and one for girls. Some other educators, like Mary Wollstonecraft, believed boys and girls should learn together. However, Trimmer thought they should be taught separately. Students learned to read, especially the Bible. They were also encouraged to be clean. Students who wanted a brush and comb were given them. Trimmer's schools became so well-known that Raikes, who inspired her, suggested people ask Trimmer for help starting their own Sunday schools. Even Queen Charlotte asked Trimmer for advice on starting a Sunday school at Windsor.

After visiting the Queen, Trimmer was inspired to write The Œconomy of Charity. This book explained how people, especially women, could start Sunday schools in their own communities. Some people worried that educating the poor would cause problems. They feared it would make them read rebellious books or not want to do hard labor. Trimmer believed that God intended some people to be poor. She argued that her schools helped reinforce this idea by teaching them to be content in their place. This book was her way of joining the big debate about Sunday schools happening in churches and in government.

Scholar Deborah Wills explained that Trimmer's book was very clever. It quietly argued against those who opposed Sunday schools. Trimmer showed how Sunday schools, if run correctly, could help keep social order. They could also strengthen the idea of different social classes. Trimmer's humble-sounding book was actually a strong statement from the middle class. It aimed to gain social, political, and religious power through moral teaching.

For example, Trimmer believed Sunday schools taught students not just to read the Bible. They also taught them how to understand it in the "correct" religious and political ways. Trimmer also argued that only the middle class should be responsible for educating the poor. By leaving out the rich, Trimmer made sure that middle-class values would be taught and passed on. This was different from other helpers like Hannah More.

O Lord, I wish to promote thy holy religion which is dreadfully neglected. I am desirous to save young persons from the vices of the age.

Trimmer also started and managed charity schools in her neighborhood. She sent promising students from her Sunday schools, which met once a week, to these charity schools, which met several times a week. She wrote in her journal that these schools seemed to offer a good chance to save many poor children from bad behavior. Trimmer also set up "schools of industry." She sent less promising students there. These schools taught girls, for example, how to knit and spin. Trimmer hoped these schools would make money from the girls' work. However, the girls were not skilled, and their products could not be sold. Trimmer saw this project as a failure.

Some modern experts have criticized Trimmer's projects as too simple and focused only on morals. They say she didn't look at the real reasons for poverty. However, others argue that poor people used these schools to learn to read. They often ignored the moral lessons they didn't agree with.

Her Writing Career

Sarah Trimmer wrote for over 25 years. She wrote between 33 and 44 books and articles. She wrote many different types of texts. These included textbooks, teaching guides, children's books, political pamphlets, and critical magazines. Many of her writings were for children. But some, like The Œconomy of Charity, were for specific adult groups. Others, like The Servant's Friend (1786–87), were for both children and adults. This book was meant to teach servants of all ages.

Throughout her career, Trimmer worked with four different publishers. By 1800, she had more books than any other author in the Newbery catalog. This catalog sold the most children's literature. Eventually, Trimmer stopped working with Joseph Johnson. She disagreed with his political views. He supported the French Revolution and published books she thought were dangerous.

An Easy Introduction to the Knowledge of Nature

Trimmer's first book was An easy introduction to the knowledge of nature, and reading the holy scriptures, adapted to the capacities of children (1780). This book continued the new ideas in children's literature started by Anna Laetitia Barbauld. In the introduction, Trimmer wrote that Isaac Watts's Treatise on Education inspired her. She felt a book about nature would help children learn about God before reading the Bible. In the story, a mother and her two children, Charlotte and Henry, go on nature walks. The mother describes the wonders of God's creation. In 1793, this book was added to the list of books supported by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. After 77 years, it had sold over 750,000 copies!

Aileen Fyfe, a historian who studies science and religion, says Trimmer's book was very different from Barbauld's. Barbauld wanted to encourage curiosity and reasoning. Trimmer, as a strong Anglican, showed nature as amazing and a sign of God's power and goodness. Trimmer's book aimed to create a feeling of wonder. Barbauld's books, however, focused on slowly gaining knowledge and thinking logically. Another difference was the role of the adult. In Barbauld's books, the teacher and student talked back and forth. In Trimmer's book, the parent controlled the conversations.

However, Donelle Ruwe, an expert on 18th-century children's literature, points out that An Easy Introduction was not completely traditional. It challenged ideas about women's roles at the time. The mother in Trimmer's book was a "spiritual leader." She showed that a woman could think deeply about religious ideas. This challenged Jean-Jacques Rousseau's ideas that women could only memorize religious rules, not truly understand them. Also, Trimmer's mother taught her children directly. She didn't use the "manipulative" tricks that the teacher in Rousseau's Emile used.

A few years later, Trimmer was inspired by Madame de Genlis's Adèle et Théodore (1782). She asked for Bible illustrations and wrote comments for them. She also published sets of prints with comments for ancient history and British history. These sets were very popular. People could buy them together (comments and prints) or separately. The prints were often hung on walls or put into books.

Working with John Marshall

The children's publisher John Marshall & Co. published The footstep to Mrs. Trimmer's Sacred history in 1785. Trimmer always believed in using pictures in children's books. Marshall, who was good at making cheap popular prints, was perfect for publishing them for her. In May 1786, Marshall published A series of prints of scripture history. These were "designed as ornaments for those apartments in which children receive the first rudiments of their education." The prints were sold in different ways: pasted on boards to hang up, in sheets, or bound into books. They also came with a small book called A description of a set of prints of scripture history. These were very successful and were reprinted for the next thirty years.

In January 1788, Mrs. Trimmer and John Marshall started a new project together. It was a monthly magazine called The family magazine; or a repository of religious instruction and rational amusement. It aimed to fight against bad books that were being read by poorer people. It usually included one picture. The magazine had religious stories for Sundays and moral stories for weekdays. It also gave advice on raising children. It compared England to other countries to show that poor people in England had more comforts. It also described animals to teach kindness to animals. The last part of the magazine had moral songs and poems. This magazine helped introduce many ideas that Hannah More later used in her famous Cheap Repository Tracts in 1795. The family magazine lasted for 18 months with Trimmer as the editor and main writer. She eventually had to stop because she was too tired.

Books for Charity Schools

Trimmer believed there weren't enough good teaching materials for charity schools. So, she decided to write her own. The books she wrote between 1786 and 1798 were used in Britain and its colonies well into the 1800s. Trimmer was good at promoting her materials. She knew her books wouldn't reach many poor children unless the SPCK funded and advertised them. She joined the society in 1787. In 1793, she sent 12 copies of her paper Reflections upon the Education in Charity Schools to the committee that chose books for funding. She argued that the charity school curriculum was old and needed to be changed. She suggested a list of seven books that she would write:

- A Spelling Book in two Parts

- Scripture Lessons from the Old Testament

- Scripture Lessons from the New Testament

- Moral Instructions from the Scriptures

- Lessons on the Liturgy from the Book of Common Prayer

- Exemplary Tales

- The Teacher's Assistant

The committee mostly accepted her plan. The Charity School Spelling Book was printed first and was used the most. It was one of the first children's books for the poor that was small but still had large print and wide margins. These features were usually only found in books for richer readers. The stories were also new. They focused on the everyday lives of ordinary children. These children climbed trees, played with fire, and begged in the streets. The book was used by Andrew Bell around 1800 for his Madras education system. It was also used by many educational groups throughout Britain and its colonies. It was even used to teach slaves in Antigua and Jamaica.

The "Scripture Lessons" became Trimmer's An Abridgement of Scripture History. This was a collection of parts from the Bible. Like the Charity School Spelling Book, it was used throughout the British education system. It was part of school life until the mid-1800s. In 1798, SPCK published Scripture Catechisms, Part I and II. These books were for teachers. The Abridgements (a shorter name for the Bible histories Trimmer published) were for students. The "Exemplary Tales" weren't written exactly as planned. But Trimmer's Servant's Friend and Two Farmers served the purpose of publishing fun moral stories. These two books were also given as Sunday school prizes. The Teacher's Assistant was a guide for teachers and was also widely used in British schools. The only books not published by the SPCK were Trimmer's versions and comments on the Book of Common Prayer, which she had printed elsewhere.

Fabulous Histories

Fabulous Histories (later called The Story of the Robins) was Trimmer's most popular book. It was first published in 1786 and stayed in print until the early 1900s. It tells the story of two families: a robin family and a human family. They learn to live together nicely. Most importantly, the human children and the baby robins must learn to be good and avoid bad behavior. Trimmer believed that being kind to animals as a child would lead to being kind to everyone as an adult.

According to Samuel Pickering, Jr., an expert on 18th-century children's books, Fabulous Histories showed how people felt about animals in the 1700s better than any other children's book. The book shares most of the ideas that Trimmer would focus on later. For example, she stressed keeping social classes as they were. Tess Cosslett, another expert, explains that the idea of social order in Fabulous Histories is quite fixed. Parents are above children, and humans are above animals. Poor people should be fed before hungry animals. However, the roles of men and women are not as clearly defined.

Moira Ferguson, an expert on the 18th and 19th centuries, says these ideas show the author's fears about the Industrial Revolution. The book attacks cruelty to animals but supports British actions abroad. The book quietly suggests conservative solutions. These include keeping order, sticking to old values, and expecting poor people to accept their situation. Foreigners who don't fit in easily are expected to leave.

Another main idea in the book is being logical. Trimmer worried about the power of made-up stories. In her introduction, she tells her young readers that her fable is not real. Animals cannot really talk. Like many critics in the 1700s, Trimmer was concerned that made-up stories could harm young readers. With more novels being read privately, there was a fear that young people, especially women, would read exciting stories without their parents knowing. Even worse, they might interpret the books however they wanted. So, Trimmer always called her book Fabulous Histories, never The Story of the Robins. This was to emphasize that it was based on facts. Also, she did not allow the book to have pictures during her lifetime. Pictures of talking birds would have made the book seem more like fiction, which she wanted to avoid. Yarde also thought that most of the characters in the book were based on Trimmer's own friends and family.

The Guardian of Education

Later in her life, Trimmer published the very important Guardian of Education (June 1802 – September 1806). This magazine included ideas for teaching children and reviews of new children's books. Although there had been one earlier attempt to review children's books regularly in Britain, Matthew Grenby says it was much smaller than Trimmer's effort. The Guardian had not only reviews but also parts from books Trimmer thought would teach her adult readers. She wanted to "check the current state of education in Britain and help shape its future." To do this, she looked at the teaching ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke, Mary Wollstonecraft, Hannah More, Madame de Genlis, Joseph Lancaster, and Andrew Bell, among others. In her "Essay on Christian Education," which was also published separately, she suggested her own complete education plan.

Trimmer took her reviewing very seriously. Her over 400 reviews showed her clear values. As Grenby explains, her first questions about any children's book were always: "Is it harmful to religion?" and "Is it harmful to loyalty to the government and the existing social order?" Religion was always Trimmer's top priority. Her focus on the Bible being completely true shows her strong beliefs. She criticized books that might scare children. She usually praised books that encouraged learning, like Anna Barbauld's Lessons for Children (1778–79).

Grenby argues that Trimmer's strong beliefs don't necessarily mean she was a rigid thinker. He points out that Trimmer, like Rousseau, believed children were naturally good. In this, she was going against old traditions, especially Puritan ideas about raising children. She also agreed with "Rousseau's main idea (while ironically attacking his works) that children should not be forced to grow up too early." This idea was later picked up by the Romantics.

The Guardian of Education helped make children's literature a recognized type of writing with its reviews. Also, in one of her early essays, "Observations on the Changes which have taken place in Books for Children and Young Persons," Trimmer wrote the first history of children's literature. She created the first list of important children's books. These books are still mentioned today by experts as key in the development of the genre.

Fairy Tales

Trimmer is perhaps most known today for her strong dislike of fairy tales. She criticized stories like those by Charles Perrault (first published in 1697). She thought they promoted an illogical view of the world. She also felt they suggested children could become successful too easily, without hard work. Cheap storybooks were often read by the poor. Trimmer tried to separate children's literature from books she linked with the lower classes. She also worried that children might get these cheap books without their parents knowing.

Trimmer criticized the values in fairy tales. She accused them of spreading superstitions and showing step-parents in a bad light. However, Nicholas Tucker argues that Trimmer wasn't just trying to censor fairy tales. By seeing fairy tales as something to criticize, she was actually similar to modern scholars. These scholars also write critically about the ideas found in some stories.

One reason Trimmer thought fairy tales were dangerous was that they led child readers into a fantasy world. Adults couldn't follow or control what children experienced there. She was also shocked by the scary pictures in some fairy tale collections. She complained that "little children, whose minds are easily affected; and who from their lively imaginations are likely to believe what strongly impresses them" should not see scenes like Bluebeard cutting off his wife's head.

French Revolution and Religion

In The Guardian of Education, Trimmer strongly spoke out against the French Revolution. She also criticized the thinkers whose ideas she believed caused it, especially Jean-Jacques Rousseau. She argued that there was a huge secret plan by French revolutionaries, who didn't believe in God and wanted democracy. Their goal was to overthrow the rightful governments of Europe. These plotters were trying to influence the minds of the younger generation. They did this through "Books of Education and Children's Books" (Trimmer's emphasis). Her views were shaped by Abbé Barruel's Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (1797–98). She included large parts of this book in the Guardian. Her fears were also increased by the ongoing wars between France and Britain in the 1790s.

Trimmer emphasized Christianity above all in her writings. She believed people should turn to God during difficult times. As M. Nancy Cutt explains, Trimmer and writers like her strongly claimed that human happiness depended on how much people followed God's will. They disagreed with moralists who thought learning should focus on reason and individual happiness in society. Trimmer and her supporters argued that French teaching ideas led to an immoral nation. Specifically, they led to ideas that questioned God and caused revolution.

Debate on School Systems

In 1789, Andrew Bell created the Madras education system. He designed it to teach British people in India. It was a system that used a hierarchy of student helpers and very few teachers. Bell argued this was cheap for the colonies. He published a book, Experiment in Education (1797), to explain his system. He thought it could be used for the poor in England. In it, he even supported many of Trimmer's own books.

A year after reading Bell's book, an English Quaker, Joseph Lancaster, used many of its ideas for his school in London. He then published his own book, Improvements in Education (1803), which repeated many of Bell's ideas. Because he was a Quaker, Lancaster did not encourage teaching the beliefs of the Established Church. Trimmer was shocked by the idea that British children didn't need to be raised within the Established Church. She wrote and published her Comparative View of the two systems in 1805. This created a split between two very similar systems.

According to F. J. Harvey Darton, an early expert on children's literature, Trimmer's impact on English education was huge. The two competing systems, Bell's and Lancaster's, were hotly debated across the country. This debate was even called "the war between Bell and the Dragon" by a cartoonist. Out of this debate came two major societies. These were the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Children of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, and the British and Foreign School Society. These societies formed the basis of Britain's later elementary school system.

Later Life and Legacy

Trimmer's husband died in 1792. This deeply affected her, as seen in her journal. In 1800, she and some of her daughters had to move to another house in Brentford. This was hard for Trimmer. She wrote in her diary about how difficult it was for a widow to deal with legal matters. She worried about leaving a house where she had lived for over 30 years. She also feared that her schools would decline if she moved too far away. She worried about being far from her children who comforted her.

She died in Brentford on 15 December 1810, and was buried at St Mary's, Ealing. There is a plaque remembering her at St. George's, Brentford. It praises her for her faith, her example as a Christian mother, and her help to the needy and uneducated. It also mentions her efforts in starting the Church School and her writings that supported the Church of England.

Trimmer's Children

Sarah Trimmer and her husband had twelve children.

| Name | Birth date | Death date | Brief biography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charlotte | 27 August 1763 | 1836 | Charlotte married Richard Moore. They had one daughter, Charlotte Selina. Charlotte Trimmer Moore died from heart problems in 1836. |

| Sarah (Selina) | 16 August 1764 | 1829 | Selina was a governess (a private teacher) for the children of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and Lady Caroline Lamb. |

| Juliana Lydia | 4 May 1766 | 1844 | Juliana Lydia might have helped her sister Selina care for the Duchess of Devonshire's children. She continued her mother's charity work in Brentford. |

| Joshua Kirby | 18 August 1767 | 17 September 1829 | Joshua Kirby married Eliza Willett Thompson in 1794. They had seven children. He held local positions in Brentford and invested in brickfields, a copper mine, and a slate quarry. He also raised merino sheep and sent them to Australia. His son, Joshua Trimmer (1795–1857), became a notable geologist. |

| Elizabeth | 21 February 1769 | 24 April 1816 | Elizabeth was often sick. She cared for her nephew James when he was dying and died just a few days before him. |

| William Kirby | 20 June 1770 | February 1811 | William Kirby married Jane Bayne in 1794. They had seven children. He owned a successful brickmaking business and collected fossils. He had a stroke in 1810 and died four months later. Three of his sons took merino sheep to Australia. |

| Lucy | 1 February 1772 | 1813 | Lucy married James Harris in 1799. They had six children. William (1807–48) became a successful soldier with the British East India Company and was knighted by Queen Victoria. He was also an artist, author, engineer, diplomat, naturalist, geographer, and sculptor. Robert (1810–65) became a successful captain in the Royal Navy and designed a curriculum for new officers. John (1808–29) joined the army and was killed at age 21 in India. Their daughter Lucy (1802–79) continued her grandmother's charity work, starting and running several Sunday schools. |

| James Rustat | 31 July 1773 | 1843 | James Rustat married Sarah Cornwallis in 1802. They had one son, James Cornwallis Trimmer (1803–16). James's wife died a month after their son was born. Sarah Trimmer's daughter, Elizabeth, cared for the baby. James Rustat Trimmer invested in his family's merino sheep business. He was described as a "brick manufacturer" on official papers. He died from senile dementia in 1843. |

| John | 26 February 1775 | 1791 | John died of consumption (a lung disease) at age fifteen. |

| Edward Decimus | 3 January 1777 | 1777 | Edward lived for only a few days. |

| Henry Scott | 1 August 1778 | 25 November 1859 | Henry Scott was sick with consumption in 1792–93. He married Mary Driver Syer in 1805. They had three sons. He was close friends with artists like J. M. W. Turner and Henry Howard (who painted his mother's portrait). He was a vicar at Heston from 1804 until his death in 1859. He started an investigation into the death of Private Frederick John White. His son Barrington (1809–60) became his curate at Heston for 27 years. He later became a domestic chaplain to the Duke of Sutherland. His son Frederick (1813–83) became a rich landowner in Heston and served as a justice of the peace. |

| Annabella | 26 December 1780 | 1785 |

List of Works

- An Easy Introduction to the Knowledge of Nature, and Reading the Holy Scriptures, adapted to the Capacities of Children (1780)

- Sacred History (1782–85) (6 volumes)

- The Œconomy of Charity (1786)

- Fabulous Histories; Designed for the Instruction of Children, Respecting their Treatment of Animals (1786)

- A Description of a Set of Prints of Scripture History: Contained in a Set of Easy Lessons (1786)

- A Description of a Set of Prints of Ancient History: Contained in a Set of Easy Lessons. In Two Parts (1786)

- The Servant's Friend (1786)

- The Two Farmers (1787)

- The Sunday-School Catechist, Consisting of Familiar Lectures, with Questions (1788)

- The Sunday-scholar's Manual (1788)

- The Family Magazine (1788–89) (periodical)

- A Comment on Dr. Watts's Divine Songs for Children with Questions (1789)

- A Description of a Set of Prints of Roman History, Contained in a Set of Easy Lessons (1789)

- The Ladder of Learning, Step the First (1789)

- A Description of a Set of Prints Taken from the New Testament, Contained in a Set of Easy Lessons (1790)

- Easy Lessons for Young Children (c.1790)

- Sunday School Dialogues (1790) (edited by Trimmer)

- A Companion to the Book of Common Prayer (1791)

- An Explanation of the Office for the Public Baptism of Infants (1791)

- An Attempt to Familiarize the Catechism of the Church of England (1791)

- The Little Spelling Book for Young Children (4th ed., 1791)

- Reflections upon the Education of Children in Charity Schools (1792)

- A Friendly Remonstrance, concerning the Christian Covenant and the Sabbath Day; Intended for the Good of the Poor (1792)

- The Ladder of Learning, Step the Second (1792)

- A Description of a Set of Prints of English History, Contained in a Set of Easy Lessons (1792)

- An Abridgement of Scripture History; Consisting of Lessons Selected from the Old Testament (1792)

- A Scriptures Catechism (1797) (2 parts)

- A Description of a Set of Prints Taken from the Old Testament (c.1797)

- The Silver Thimble (1799)

- An Address to Heads of Schools and Families (1799?)

- The Charity School Spelling Book (c.1799) (2 parts)

- The Teacher's Assistant: Consisting of Lectures in the Catechised Form (1800)

- A Geographical Companion to Mrs. Trimmer's Scripture, Antient, and English Abridged Histories, with Prints (1802)

- A Help to the Unlearned in the Study of the Holy Scriptures (1805)

- An Abridgement of the New Testament (1805?)

- A Comparative View of the New Plan of Education Promulgated by Mr. Joseph Lancaster (1805)

- The Guardian of Education (1802–06) (periodical)

- A New Series of Prints, Accompanied by Easy Lessons; Being an Improved Edition of the First Set of Scripture Prints from the Old Testament (1808)

- A Concise History of England (1808)

- Instructive Tales: Collected from the Family Magazine (1810)

- An Essay on Christian Education (1812) (published after her death)

- Sermons, for Family Reading (1814) (published after her death)

- Some Account of the Life and Writings of Mrs. Trimmer (1814) (published after her death)

- A Description of a Set of Prints of the History of France, Contained in a Set of Easy Lessons (1815) (published after her death)

- A Selection from Mrs. Trimmer's Instructive Tales; The Good Nurse... (1815) (published after her death)

- Miscellaneous Pieces, Selected from the Family Magazine (1818) (published after her death)

- Prayers and Meditations Extracted from the Journal of the Late Mrs. Trimmer (1818) (published after her death)

- A Selection from Mrs. Trimmer's Instructive Tales; The Rural Economists... (1819) (published after her death)

Images for kids

-

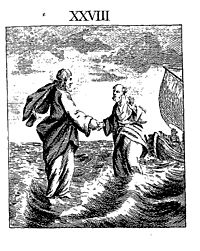

From Trimmer's A Description of a Set of Prints Taken from the New Testament: "Jesus spake unto them, saying, It is I, be not afraid. And Peter answered and said Lord, if it be thou, bid me come to thee on the water: and he said, Come. And when Peter was come out of the ship, he (through the power of CHRIST) walked on the water likewise; but when he saw the wind boisterous, his faith or belief in CHRIST'S power, failed, he was afraid, and beginning to sink, he cried out, Lord, save me! And immediately JESUS stretched forth his hand and caught him, saying, O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?"

See also

In Spanish: Sarah Trimmer para niños

In Spanish: Sarah Trimmer para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |