Estates of the realm facts for kids

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were a way of dividing people into different social groups in Christian Europe. This system was used from the Middle Ages until the early modern period. Over time, different countries had their own ways of dividing society.

The most famous system was in France, called the Ancien Régime (Old Rule). It had three estates:

- The First Estate was the clergy (church leaders).

- The Second Estate was the nobles (rich families with special titles).

- The Third Estate included everyone else, like peasants (farmers) and bourgeoisie (city workers and merchants).

Some places, like Sweden and Russia, had a four-estate system. They separated city merchants (burghers) and rural commoners into different groups. In England, there were two main groups: the lords (nobility and clergy) and the "commons." This led to the two parts of the English Parliament: the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Today, when people talk about "the three estates," they might be thinking about the modern way governments are divided into different parts: the group that makes laws, the group that carries them out, and the group that judges them. The term "fourth estate" often refers to the news media, which acts as a watchdog on power.

Contents

Moving Up in Society

During the Middle Ages, it was very hard to move from one social class to another. People usually stayed in the group they were born into.

The Church was one of the few places where common people could rise in rank. They might become a vicar general or an abbot (head of a monastery). However, the highest church jobs, like bishops, usually went to people from noble families. Since church leaders could not marry, any social rise was only for that person, not their children. Sometimes, people used their family connections to get ahead, which was called nepotism.

Another rare way to move up was through great success in the military or business. But even then, these families needed the king's help to become nobles. Since noble families sometimes died out, new nobles were sometimes needed.

How the Estates Worked

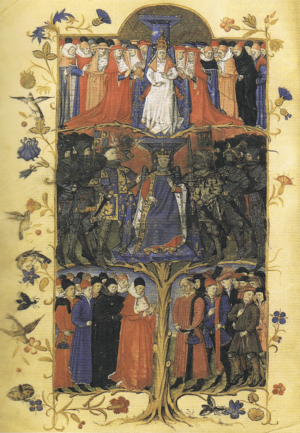

People in the Middle Ages believed society was made up of clear, separate groups. These groups were called "estates" or "orders." They weren't just about wealth or class. They included all kinds of social roles, jobs, and groups.

For example, there were the main estates of the realm. But there were also groups like married people, single people, and even different types of knights. This way of thinking meant that a person's place in society was usually set at birth.

Commoners were always seen as the lowest group. However, the higher estates depended on the commoners for food and goods. This led to commoners being divided further into city dwellers (burghers or bourgeoisie) and country people (peasants or serfs). A person's estate was usually passed down from their father, much like a caste system. Some people were born outside these main estates and had no political rights.

Groups that advised or made laws for the king were often organized by these estates. These meetings of the estates became early parliaments. Kings often asked the estates to promise their loyalty to make their power stronger. Today, in most countries, these old estates no longer have special legal rights. They are mostly important for understanding history. However, in Britain, the House of Lords still shows a link to the old system.

A famous writing called "What Is the Third Estate?" was written in 1789 by a man named Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès. It talked about the importance of the Third Estate just before the French Revolution.

History of the Estates

After the Western Roman Empire fell, many kingdoms grew in Europe. The Catholic Church also became very powerful, guiding people's religious and moral lives. Kings and the Church often relied on each other. But as kingdoms grew stronger, their goals sometimes differed from the Church's ideas.

The new rulers of the land were mostly warriors. But fighting was expensive and required a lot of training and resources. At the same time, Europe saw a big increase in population, farming, new inventions, and cities. These changes also affected how society was divided.

A French historian named Georges Duby showed that in the early 1000s, a bishop named Gerard of Florennes was one of the first to explain why European society was divided into three estates.

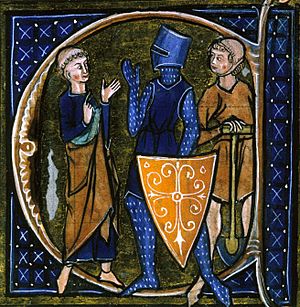

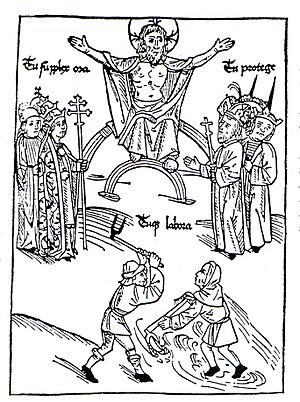

By the 11th and 12th centuries, thinkers believed society had three parts: those who pray (clergy), those who fight (nobles), and those who work (commoners). The clergy's structure was set by 1200. The fighting group was powerful and sometimes challenged kings. The working group, which included peasants, skilled workers, merchants, and others, grew quickly and helped Europe's economy boom.

Most European thinkers by the 12th century thought that having a king was the best way to govern. They believed it copied God's rule over the universe.

Estates in France

France under the Ancien Régime (before the French Revolution) had three main estates. The king was not part of any estate.

First Estate: The Clergy

The First Estate included all the clergy (priests, monks, nuns). They were often divided into "higher" clergy (like bishops) and "lower" clergy (like parish priests). The higher clergy usually came from noble families. By the time of King Louis XVI, all bishops in France were nobles.

The "lower clergy" made up about 90% of the First Estate. In 1789, there were about 130,000 people in the First Estate, which was about 0.5% of France's population.

Second Estate: The Nobility

The Second Estate included the French nobility and the royal family (except the king himself).

Nobles were traditionally divided into two groups: "nobility of the sword" (old military families) and "nobility of the robe" (officials who worked in royal justice and government).

The Second Estate was about 1.5% of France's population. Under the old system, nobles did not have to do forced labor on roads or pay most taxes, like the salt tax or the main direct tax. This tax exemption was a big reason why they didn't want political changes.

Third Estate: The Commoners

The Third Estate included everyone who was not in the First or Second Estate. It was divided into city people (wage-workers) and country people (peasants). This group made up over 98% of France's population.

Peasants could be free (owning their own land) or villeins (working on a noble's land). Free peasants paid very high taxes compared to the other estates and wanted more rights. The First and Second Estates depended on the Third Estate's labor, which made their lower status even more unfair.

When the French Revolution began, there were about 27 million peasants in the Third Estate. They had a hard life with physical work and often not enough food. Most people were born into this group and stayed there their whole lives. It was very rare for someone from this group to join another estate. If it happened, it was usually for great bravery in battle or by joining the Church.

Estates General Meeting

The Estates General was a big meeting of representatives from all three estates. It was first called by King Philip IV in 1302. It met on and off until 1614, then not again for over 170 years.

In the late 1780s, France was in deep debt. The finance minister, Jacques Necker, tried to fix things. There was also a severe food shortage in the winter of 1788–89, causing widespread anger. King Louis XVI called the Estates General meeting in 1789 to solve these problems.

However, the Third Estate representatives (612 of them) wanted big changes. They were against the king's plans and the nobles' wishes to keep their tax exemptions. When the king tried to close the meeting, the Third Estate refused to leave. Many lower clergy and some nobles joined them. The king had to give in. This meeting became a spark for the French Revolution.

In June 1789, the Estates General changed its name to the National Assembly. They wanted to find solutions without the king's control. This independent meeting is seen as the start of the French Revolution. Later, it became the National Constituent Assembly and began to govern France after the king fled.

Estates in Great Britain and Ireland

In England, the system of estates did not stop people from moving up in society as much as in other places. However, the English Parliament was set up based on the estates. It included the "Lords Spiritual and Temporal" (church leaders and nobles) and the "Commons" (common people). These two groups began meeting separately in the 1300s.

Even today, the British Parliament still has a House of Commons and a House of Lords. The House of Lords includes nobles (Lords Temporal) and bishops of the Church of England (Lords Spiritual).

Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland was also called the Three Estates. It included:

- The first estate of church leaders (bishops and abbots).

- The second estate of nobles (dukes, earls, and other lords).

- The third estate of representatives from royal towns.

Unlike England, all members of the Scottish Parliament sat in the same room. Universities also had representatives in Parliament, a system later adopted by England.

Ireland

After the Norman invasion in the 1100s, Ireland's government was set up like England's. The Parliament of Ireland also had estates. It included the king's council, nobles, and church leaders. Later, elected representatives from counties and towns joined.

The Irish Parliament was divided into the Irish House of Lords and the Irish House of Commons. Church representatives formed a separate house until 1537, when they were removed for opposing the Irish Reformation. The Parliament of Ireland was dissolved in 1800, and Ireland joined Great Britain to form the United Kingdom. Irish representatives then went to the British Parliament in London.

Estates in Sweden and Finland

In Sweden (which included Finland at the time), and later in Russia's Grand Duchy of Finland, there were four estates:

- Nobility

- Clergy

- Burghers (city dwellers, merchants, and craftsmen)

- Land-owning peasants

All members of these estates were free men. They had specific rights and could send representatives to the Riksdag (parliament). The Riksdag had four separate chambers, one for each estate. To pass a law, at least three estates had to agree.

There were also many people who did not belong to any estate. Unlike in other countries, people in Sweden and Finland were not automatically peasants unless they owned land. These "estateless" people included poor farmers, servants, and unemployed people. They had no political rights and could not vote. They had to be employed by someone from an estate, or they could be punished for being homeless. This rule lasted in Finland until 1883.

In Sweden, the Riksdag of the Estates was replaced by a two-chamber parliament in 1866. This new system gave political rights to anyone with a certain income or property. In Finland, this system of estates lasted until 1906. By then, most of the population did not belong to any estate and had no political voice. This led to reforms that created a modern parliamentary system.

Estates in the Low Countries

The Low Countries (modern Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) did not have a States General (a general assembly of estates) until 1464. Later, representatives from the different provinces (counties, duchies) would meet and ask for more freedoms.

After some conflicts in the late 1500s, the States General in the Dutch Republic declared they would no longer obey the King of Spain. Without a king, the States General became the main governing power. It dealt with issues important to all seven provinces that formed the Dutch Republic.

The States General was made up of representatives from the nobility and the cities. The clergy were no longer represented. In 1795, the States General of the Dutch Republic was abolished. A new parliament was created where all men were considered equal.

After gaining independence in 1813, the name "States General" was brought back for the new parliament. In 1815, when the Netherlands united with Belgium and Luxembourg, the States General was divided into two chambers: the First Chamber and the Second Chamber. Today, the Second Chamber is the most important, with members elected by the people.

Estates in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire had an Imperial Diet (Reichstag).

- The clergy were represented by independent prince-bishops and abbots.

- The nobility included independent rulers like princes, dukes, and counts.

- The burghers were representatives from independent imperial cities.

Many people, like knights and villagers, had no representatives in the Imperial Diet. The Diet's power was limited. Large noble or church lands also had their own local estates that held great power.

Estates in Russia

In the later Russian Empire, the estates were called sosloviyes. The four main estates were: nobility, clergy, rural dwellers, and urban dwellers. This division was based on tradition, occupation, and formal rules. For example, voting in the Duma (parliament) was done by estates.

Estates in Portugal

In the Medieval Kingdom of Portugal, the "Cortes" was a meeting of representatives from the nobility, clergy, and city dwellers. The King of Portugal could call or dismiss it whenever he wanted.

Estates in Catalonia

The Catalan Parliament was first set up in 1283 as the Catalan Courts. Historians consider it an important example of a medieval parliament. Some even say it was better organized than the parliaments of England or France in the 1300s.

The Catalan Courts had three estates:

- The "military estate" with noble representatives.

- The "church estate" with religious leaders.

- The "royal estate" with representatives from free towns under the king's rule.

This parliament was abolished in 1716 after a war.

See also

In Spanish: Estamento para niños

In Spanish: Estamento para niños

- Fourth Estate

- Social class

- Caste

- What Is the Third Estate?