Thomas A. Dorsey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas A. Dorsey

|

|

|---|---|

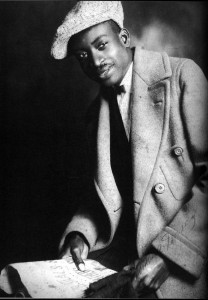

Thomas Dorsey during his "Georgia Tom" blues period, late 1920s

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Thomas Andrew Dorsey |

| Also known as |

|

| Born | July 1, 1899 Villa Rica, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | January 23, 1993 (aged 93) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments | Piano |

| Years active | 1924–1984 |

| Associated acts | |

Thomas Andrew Dorsey (born July 1, 1899 – died January 23, 1993) was an American musician and composer. He played a very important role in creating early blues and 20th-century gospel music. He wrote 3,000 songs, and about a third of them were gospel songs. Two of his most famous gospel songs are "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" and "Peace in the Valley". Millions of copies of these songs were sold.

Dorsey grew up in a religious family in Georgia. He learned a lot about music by playing blues at parties in Atlanta. Later, he moved to Chicago and became a skilled composer of jazz and vaudeville music. He became famous playing with blues singer Ma Rainey. He also had a successful recording career with guitarist Tampa Red, where he was known as "Georgia Tom."

After a special spiritual experience, Dorsey decided to focus on writing religious music. He believed that blues and church music were similar in many ways, except for the words. He thought songs could help explain spoken sermons. Dorsey worked as the music director at Chicago's Pilgrim Baptist Church for 50 years. He brought new ideas to church music, like adding improvisation and encouraging people to clap, stomp, and shout. At the time, these actions were often seen as too wild for church. In 1932, he helped start the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses. This group trained musicians and singers across the U.S. and is still active today. Many famous gospel singers, like Sallie Martin and Mahalia Jackson, worked or trained with Dorsey.

People called Thomas A. Dorsey the "Father of Gospel Music." He helped make gospel blues popular in black churches across the United States. This new style of music then influenced American music and society in many ways.

Contents

Early Life and Music (1899–1918)

Thomas A. Dorsey was born in Villa Rica, Georgia. He was the first of three children. His father, Thomas Madison Dorsey, was a minister and farmer. His mother was Etta Plant Spencer. The family worked on a small farm. Thomas's father also preached at nearby churches and taught children in a one-room schoolhouse. Young Thomas often went with him and listened to the lessons.

Music and religion were very important in the Dorsey family. Thomas heard many different kinds of music when he was young. His family owned an organ, which was unusual for black families then. His mother played it during his father's church services. His uncle was also a musician who played country blues on the guitar. In rural Villa Rica, Dorsey heard old slave spirituals and a singing style called "moaning." This style used long, drawn-out notes and was common among black people in the South. He also heard the Protestant hymns his father liked. When his father preached in other towns, Thomas and his mother went to a church that used shape note singing. The way they harmonized made a big impression on him.

When Thomas was eight, his family moved to Atlanta to find better opportunities. It was a hard change for the family. Thomas felt alone, struggled in school, and eventually left after fourth grade when he was twelve.

Without a clear path, Dorsey started going to shows at the 81 Theater. This theater had blues musicians and live vaudeville acts. Soon, he began selling snacks there. He wanted to join the theater band, so he practiced for many hours on his family's organ and a relative's piano. He learned melodies he heard and studied with musicians at the theater and local dance bands, always playing blues. Because he worked at spontaneous events, he became very good at improvising. He also learned to read musical notation.

Blues Career and New Ideas (1919–1925)

In 1919, Dorsey moved to Chicago looking for more challenges. He found that his blues style was not as popular as the faster jazz music there. There was more competition for jobs. Dorsey then started writing songs. He copyrighted his first song in 1920, called "If You Don't Believe I'm Leaving, You Can Count the Days I'm Gone." This made him one of the first musicians to copyright blues music.

Dorsey wasn't sure about writing church music until 1921. He heard W. M. Nix sing "I Do, Don't You?" at the National Baptist Convention. Nix sang in a way that stretched some notes and sped up others. Dorsey liked the freedom and emotion this style brought to hymns. He felt it could help singers show more joy and excitement to churchgoers. After hearing Nix, Dorsey felt very inspired. He later said his "heart was inspired to become a great singer and worker in the Kingdom of the Lord." This experience led him to copyright his first religious song in 1922, "If I Don't Get There." It was in the style of Charles Albert Tindley, whom Dorsey admired. But religious music didn't earn him enough money, so he kept working in blues.

Two of his blues songs were recorded by Monette Moore, and another by Joe "King" Oliver. This made Dorsey one of Chicago's top blues composers. He became a music arranger for Paramount Records and the Chicago Music Publishing Company. In 1923, he became the pianist and leader of the Wild Cats Jazz Band. They played with Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, a powerful blues singer. Rainey sang about sad times and connected deeply with her audiences. Dorsey remembered the night Rainey opened at Chicago's biggest black theater as "the most exciting moment in my life."

Dorsey worked with Rainey for two years. He wrote and arranged her music in blues, vaudeville, and jazz styles. In 1925, he married Nettie Harper. Rainey hired Nettie as a wardrobe mistress so she could travel with Dorsey on tour.

Moving Towards Gospel Music (1926–1930)

In 1928, Dorsey had another spiritual experience. He went to a church service, and after the minister prayed for him, Dorsey felt a great change. After this, he promised to focus all his efforts on gospel music. When a close friend died, Dorsey was inspired to write his first religious song with a blues feel, "If You See My Savior, Tell Him That You Saw Me."

As blues music became more popular in the 1920s, many black churches did not approve of it. Music in established black churches in Chicago usually came from hymnals and was played exactly as written. It was often meant to show off the choir's skill, not to share a spiritual message. Many churches wanted their music to sound fancy, like classical European composers such as Handel or Mozart. Actions like clapping, stomping, or changing the words, rhythm, or tune were not allowed. They were seen as rude and disrespectful.

Dorsey tried to sell his new sacred music by printing thousands of copies of his songs. He went door-to-door to churches and publishers, but he didn't have much success. So, he went back to blues music. He recorded "It's Tight Like That" with guitarist Hudson "Tampa Red" Whittaker. This song sold over seven million copies. Dorsey and Tampa Red were known as "Tampa Red and Georgia Tom" or "The Famous Hokum Boys." They worked together on 60 songs between 1928 and 1932. They even created the term "Hokum" for their simple guitar and piano style.

Dorsey wasn't sure if gospel music could support him. But in 1930, he found out that Willie Mae Ford Smith had sung "If You See My Savior" at the National Baptist Convention. People loved it so much that she was asked to sing it two more times. Dorsey sold 4,000 printed copies of his song that day. Inspired by this success, he formed a choir at Ebenezer Baptist Church. Dorsey and the music director, Theodore Frye, trained the choir to sing his songs with a gospel blues sound. This meant lively, joyful performances with stretched notes, rhythmic clapping, and shouts. At their first performance, Frye walked around and sang with the choir. Dorsey even jumped up from the piano in excitement. The pastor at Pilgrim Baptist Church, Chicago's second largest black church, saw how much the music moved the people. He hired Dorsey as music director, allowing him to work only on gospel music.

Leading a Gospel Movement (1930–1933)

This new music style started to become popular in Chicago. Dorsey's musical friends, Theodore Frye, Magnolia Lewis Butts, and Henry Carruthers, encouraged him to start a convention. Musicians could learn gospel blues there. In 1932, Dorsey helped create the Gospel Choral Union of Chicago, which later became the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses (NCGCC). But at the same time, his wife Nettie died during childbirth, and their baby son died 24 hours later. His deep sadness led him to write one of his most famous songs, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord".

New groups of the NCGCC opened in St. Louis and Cleveland. Dorsey was now at the center of gospel music in Chicago. He dealt with his sadness by focusing on selling his songs. He worked with many musicians who helped sell his sheet music by traveling to churches around Chicago. They practiced their sales pitches in Dorsey's simple room. Frye and Sallie Martin were two of the first and best singers who helped Dorsey sell his music. Dorsey and Martin started a company called Dorsey House of Music. It was the first black-owned gospel music publishing company in the U.S. His sheet music sold so well that it became as popular as the Bible in black households. He also helped many young musicians, including training a teenage Mahalia Jackson when she first came to Chicago.

Besides lively choir performances, Dorsey also started adding faster Negro spirituals, which he called "jubilees," to church services. Some older church members who liked more formal music didn't like these changes. This caused arguments in and between Chicago's black churches. Dorsey often said he had "been kicked out of the best churches in the country." He faced resistance from ministers, musicians, and church members. Some thought the blues shouting made worship less serious. Others didn't like lively music taking attention away from the minister's sermon, or women singing spiritual messages instead of male preachers.

At the same time, Chicago's black churches were changing. Hundreds of thousands of people from the South, who liked blues music, moved to Chicago. They started to outnumber the older church members who preferred classical European music. Ministers who would not have changed their music programs a few years before became more open to new ideas. Church services changed in many ways to welcome these new people. This helped churches attract new members and pay their bills.

Despite the disagreements, gospel blues quickly became established in Chicago's black churches. In 1933, Dorsey led a 600-person choir at the second NCGCC meeting. The NCGCC now had 3,500 members in 24 states. Black gospel choirs were asked to perform at several white churches in Chicago. Dorsey's own Pilgrim Baptist Church choir even performed at the 1933 World's Fair.

Later Life and Legacy (1934–1993)

Dorsey lived a quiet life even though he was very influential. He didn't look for fame. He preferred to stay as the music director at the 3,000-seat Pilgrim Baptist Church and run his publishing company. As the head of the NCGCC, he traveled the "gospel highway." This was a route of churches and other places across the U.S. where he trained singers and choirs. Between 1932 and 1944, he held "Evenings with Dorsey" to teach new singers how to perform his songs. He also toured a lot with Mahalia Jackson in the 1940s. By then, she was the most important gospel singer in the world. Dorsey never thought of himself as a strong singer. He recorded gospel music sometimes until 1934, and his last two songs were in 1953, but he kept writing.

During his blues period, Dorsey dressed very neatly and formally. He kept this style in his gospel work. People described him as dignified and often serious. One writer said he looked like a "truly mesmerizing figure, the stuff of which legends are made." However, once you knew him, Dorsey could offer a "charming smile," and his excitement often made his voice go high. When he wrote to his sister that he was lonely and wanted to be around children, she sent Dorsey's niece Lena McLin to live with him. McLin remembered that her uncle was "soft-spoken, not loud at all, and very well dressed... he always had a shirt and a tie and a suit, and he was always elegant, very mannerly, very nice. And he would sit at the piano and play something and say, 'That's good stuff!'"

He married Katheryn Mosley in 1941. They had two children, a son named Thomas M. "Mickey" and a daughter, Doris. Even with a family, he stayed active in music, attending many events each year. Katheryn Dorsey said, "I'd have to catch him between trains because he was hardly ever at home... The only thing he cared about was saving souls through his music."

To do this, Dorsey traveled outside the U.S. to Mexico, the Caribbean, Europe, and the Middle East. He remembered visiting Damascus, Syria. A man recognized him in a bathroom there. A group of 150 tourists asked him to sing "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" right then. Dorsey started singing, but the group from many countries took over: "And they knew it in Damascus, too. Folk was wipin' their eyes, and some cryin' and bawlin' on, and I told ‘em, 'What is this happenin' here? I'll never get out of this place alive.'"

When he gave interviews later in his life, he never said anything bad about blues music or his time playing it. He stayed in touch with his blues musician friends. He said, "I'm not ashamed of my blues. It's all the same talent. A beat is a beat whatever it is." Dorsey started to slow down in the 1970s and began showing signs of Alzheimer's disease. He retired from Pilgrim Baptist Church and the NCGCC soon after, but he still participated and performed when he could. He and the NCGCC were featured in the famous documentary Say Amen, Somebody in 1982. The 1981 meeting shown in the film was the last convention he could attend. Dorsey died from Alzheimer's in 1993, listening to music on a Walkman. He is buried at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

Dorsey's Impact on Music

Gospel historian Horace Boyer says that gospel music has "no more imposing figure" than Dorsey. The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music states that he "defined" the genre. Folklorist Alan Lomax claims that Dorsey "literally invented gospel." In Living Blues, Jim O'Neal compares Dorsey in gospel to W. C. Handy, who was the first and most important blues composer. Dorsey developed his tradition from the inside, rather than just "discovering" it. Although he wasn't the first to mix blues with religious music, he earned the title "Father of Gospel Music." This was because of his strong efforts to make it used as worship songs in black Protestant churches.

Throughout his career, Dorsey wrote more than 1,000 gospel songs and 2,000 blues songs. Mahalia Jackson thought this was as impressive as Irving Berlin's work. A manager of a gospel group in the 1930s said that songs written by Dorsey and others copying him spread so fast that they were called "dorseys." Horace Boyer says this popularity came from "simple but beautiful melodies," easy harmonies, and room for singers to improvise. Dorsey was also good at writing songs that spoke to the hopes, fears, and dreams of poor African Americans, but also to all people.

Besides his amazing songwriting, Dorsey's influence in the gospel blues movement brought changes to black communities. He introduced ways of doing things and standards for gospel choirs that are still used today. At the start of worship services, Dorsey told choirs to march from the back of the church to the choir-loft in a special way, singing all the time. Choir members were encouraged to move while singing, rocking and swaying with the music. He insisted that songs be memorized instead of reading music or words. This freed the choir members' hands to clap. He also knew that most choir singers in the early 1930s couldn't read music. Dorsey refused to give musical notes or use them when directing. He felt the music was only a guide, not something to follow strictly. Adding all the extra parts in gospel blues would make the notes too complicated. Instead, Dorsey asked his singers to rely on feeling.

When leading rehearsals, Dorsey was strict and serious. He demanded that members practice regularly and live their lives by the same values in their songs. For women, this included not wearing make-up. Choirs were mostly made up of women, often untrained singers. Dorsey worked with them personally, encouraging many women who had not been very involved in church before to become active. The NCGCC in 1933 was largely a "women's movement," with nine of the thirteen main leadership positions held by women.

Because of Dorsey's influence, the meaning of gospel music changed. It became religious music that helped people release pain and suffering, especially in black churches. He filled his written music with joy and hope. He directed his choirs to perform with uplifting energy as they sang. The healing power of gospel music became very important to the black experience during the Great Migration. This was when hundreds of thousands of black Southerners moved to Northern cities like Detroit, Washington, D.C., and especially Chicago between 1919 and 1970. These migrants were escaping poverty and unfair laws in the Jim Crow South. They created strong communities through church choirs, which were also social clubs. These clubs gave them a sense of purpose and belonging.

Gospel music had a "golden age" between 1940 and 1960. During this time, recordings and radio shows featured singers who had all been trained by Dorsey or his students. Dorsey is remembered as the father of gospel music. Other famous titles came from his choirs: Sallie Martin was called the mother of gospel, Mahalia Jackson the queen of gospel, and James Cleveland the king of gospel. In 1936, members of Dorsey's junior choir became the Roberta Martin Singers, a successful recording group. They set the standard for gospel groups. After Dorsey, R&B artists like Dinah Washington, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, Little Richard, James Brown, and the Coasters recorded both R&B and gospel songs. They moved easily between the two styles, just like Dorsey did, bringing parts of gospel to wider audiences.

Even with racial segregation in churches and the music industry, Dorsey's music was popular with many different groups. Important hymnal publishers started including his songs in the late 1930s, making sure his music would be sung in white churches too. His song "Peace in the Valley", written in 1937 for Mahalia Jackson, was recorded by Red Foley in 1951 and Elvis Presley in 1957. Each version sold over a million copies. Foley's version has been added to the National Recording Registry as a culturally important recording.

"Take My Hand, Precious Lord" was the favorite song of Martin Luther King Jr.. He asked Dorsey to play it for him the night before he was assassinated. Mahalia Jackson sang it at King's funeral. Four years later, Aretha Franklin sang it at Jackson's funeral. Since it was first written, it has been translated into 50 languages.

Chicago held its first gospel music festival to honor Dorsey in 1985. It has happened every year since then. Although he never went back to his hometown, efforts to honor Dorsey in Villa Rica, Georgia, began a week after his death. Mount Prospect Baptist Church, where his father preached and Dorsey learned music, was named a historic site. A historical marker was placed where his family's house once stood. The Thomas A. Dorsey Birthplace and Gospel Heritage Festival, started in 1994, is still active.

As of 2020, the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses has 50 groups around the world.

Honors and Awards

- Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, joined in 1979

- Georgia Music Hall of Fame, joined in 1981

- Gospel Hall of Fame, joined in 1982

- Governor's Award for the Arts in Chicago, given 1985

- National Trustees Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, given 1992

- National Recording Registry: sound recordings considered "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress

- "If I Could Hear My Mother Pray Again" (1934), added in 2007 – recorded by Dorsey

- "Peace In The Valley" by Red Foley and the Sunshine Boys (1951), added in 2006

- Precious Lord: New Recordings of the Great Songs of Thomas A. Dorsey by Various Artists (1973), added 2002

- Blues Hall of Fame: Performer, joined in 2018

- "It's Tight Like That": Classic of Blues Recording–Single or Album Track, joined in 2014

- "Future Blues" by Willie Brown: Classic of Blues Recording–Single or Album Track, joined in 2020/2021 (based on "Last Minute Blues", written by Dorsey)

See also

In Spanish: Thomas A. Dorsey para niños List of people considered a founder in a Humanities field

In Spanish: Thomas A. Dorsey para niños List of people considered a founder in a Humanities field

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |