Thomas Chatterton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Chatterton

|

|

|---|---|

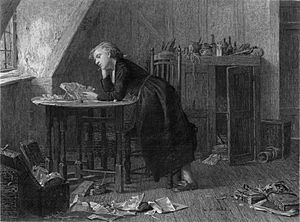

Chatterton's Holiday Afternoon engraved by William Ridgway, after W.B. Morris, pub. 1875

|

|

| Born | 20 November 1752 Bristol, England |

| Died | 24 August 1770 (aged 17) Holborn, London, England |

| Pen name | Thomas Rowley, Decimus |

| Occupation | Poet, forger |

Thomas Chatterton (born November 20, 1752 – died August 24, 1770) was an English poet. He passed away at just 17 years old. His unique life and writings greatly influenced artists of the Romantic period. Famous poets like Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth, and Coleridge were inspired by him.

Even though he grew up without a father and in a poor family, Chatterton was a very dedicated student. He started publishing mature poems by age 11. He was able to make people believe his poems were written by an imaginary 15th-century poet named Thomas Rowley. This worked because most people back then didn't know much about medieval poetry. However, a famous writer named Horace Walpole eventually doubted him.

At 17, Chatterton moved to London to find ways to publish his political writings. He had impressed important people like the Lord Mayor, William Beckford, and a political leader, John Wilkes. But he didn't earn enough money to live, and sadly, he took his own life. His interesting life and early death caught the attention of many Romantic poets. A play about him by Alfred de Vigny is still performed today. Also, the famous painting The Death of Chatterton by Henry Wallis shows his lasting impact.

Contents

Thomas Chatterton's Early Life

Thomas Chatterton was born in Bristol, England. His family had a long history of being the sexton (a church official) at St Mary Redcliffe church. His father, also named Thomas Chatterton, was a musician and a poet. He also collected old coins (a numismatist) and was interested in hidden knowledge (the occult). He had been a singer at Bristol Cathedral and taught at the Pyle Street free school.

Chatterton's father died before he was born. So, his mother started a girls' school and did sewing to support the family. Thomas went to Edward Colston's Charity, a special school in Bristol for poor children. There, he learned reading, writing, math, and religious lessons (the catechism).

A Boy Fascinated by History

Chatterton was always very interested in his uncle, the church sexton, and the old St Mary Redcliffe church. He loved looking at the statues of knights and important people on the altar tombs (stone tombs in the church). He also found old wooden chests in a special room above the church porch. This room, called a muniment room, held very old parchment documents, some from as far back as the Wars of the Roses (a long time ago!).

Chatterton learned his first letters from the colorful, decorated letters in an old music book. He learned to read from a Bible printed in an old style. His sister said he didn't like reading small books. From a young age, he was a bit stubborn and didn't play much with other children. Some thought he was slow at learning. But his sister remembered him saying he wanted an angel with a trumpet painted on his bowl, "to trumpet my name over the world."

A Special Attic Study

From a young age, Chatterton would sometimes go into deep thought, sitting for hours as if in a trance. He would also cry for no clear reason. Being often alone helped him become quiet and private. It also made him love mysteries, which greatly shaped his poetry. When he was six, his mother started to see how smart he was. By age eight, he loved books so much he would read and write all day if left alone. By age 11, he was already writing for a local newspaper, Felix Farley's Bristol Journal.

A religious event called his confirmation inspired him to write some religious poems for the paper. In 1763, a church official destroyed an old cross that had been in the St Mary Redcliffe churchyard for over 300 years. Chatterton felt very strongly about this. On January 7, 1764, he sent a funny, critical poem about the church official to the local newspaper. He also loved to lock himself in a small attic room. This was his special study. There, with books, old parchments he had found from the church, and drawing supplies, he imagined himself living with his heroes from the 15th century.

His Secret Poems: Thomas Rowley

The first of Chatterton's literary mysteries was a poem called "Elinoure and Juga." He showed it to Thomas Phillips, a teacher at Colston's Hospital (where Chatterton was a student). Chatterton pretended the poem was written by a 15th-century poet. He stayed at Colston's Hospital for more than six years. Only his uncle encouraged the students to write poetry. Chatterton kept his more daring writing adventures a secret.

He spent his small allowance on borrowing books from a circulating library (a place where you could rent books). He also made friends with people who collected books. This helped him read works by old writers like John Weever and William Dugdale. He also read Chaucer and Spenser. He found an old book of poems by Elizabeth Cooper, which gave him many ideas for his own made-up works.

Creating a New Language

Chatterton's special "Rowleian" language, which sounded old, mostly came from studying a dictionary called Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum by John Kersey. It seems he didn't know much about Chaucer himself. He spent most of his holidays at his mother's house, often in his favorite attic study. He mostly lived in his own imaginary world. This world was set in the mid-15th century, during the time of King Edward IV. In his stories, a rich Bristol merchant named William II Canynges (who died in 1474) was still alive. Canynges had been mayor of Bristol five times and helped rebuild St Mary Redcliffe church. Chatterton knew Canynges from his statue in the church. He imagined Canynges as a wise supporter of art and literature.

The Imaginary Monk

Chatterton soon created the story of Thomas Rowley. Rowley was an imaginary monk from the 15th century. Chatterton used the name Thomas Rowley as his own pen name for his poetry and history writings. A psychoanalyst named Louise J. Kaplan suggested that not having a father played a big part in him creating Rowley. She thought that because he was raised by his mother and sister, he unconsciously created Rowley to have a father-like figure. He also imagined becoming a famous poet who could save his mother from poverty.

It's interesting to note that at the same time, there was a real poet named Thomas Rowley in Vermont, USA. However, it's very unlikely Chatterton knew about him.

Seeking Support for His Work

To make his dreams come true, Chatterton started looking for people to support his writing. First, he tried in Bristol. He met William Barrett, George Catcott, and Henry Burgum. He helped them by giving them his "Rowley" writings. William Barrett, who studied old things, used only these fake writings for his book History and Antiquities of Bristol (1789). This book ended up being a huge failure.

Since the people in Bristol weren't paying him enough, Chatterton turned to the richer Horace Walpole. In 1769, Chatterton sent Walpole examples of Rowley's poems and a piece called "The Ryse of Peyncteynge yn Englade." Walpole offered to print them "if they have never been printed." But later, when he found out Chatterton was only 16 and the Rowley pieces might be fakes, he rudely sent him away.

Political Writings and Leaving Bristol

Walpole's rejection hurt Chatterton badly, and he wrote very little for a summer. After that, he started focusing on writing for magazines and about politics. He switched from Farley's Bristol Journal to London magazines like the Town and Country Magazine. He started writing like a famous anonymous writer called Junius. He wrote against powerful figures like the Duke of Grafton, the Earl of Bute, and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess of Wales.

He had just sent one of his strong political articles to the Middlesex Journal. Then, on Easter Eve, April 17, 1770, he wrote his "Last Will and Testament." This was a mix of jokes and serious thoughts. In it, he hinted that he planned to end his life the next evening. Among his satirical (joking) gifts, he left his "humility" to one person and his "modesty" to another. He also left "to Bristol all his spirit and disinterestedness," saying these things hadn't been seen there since the days of Canynge and Rowley. More seriously, he mentioned Michael Clayfield, a friend who understood him. This "will" might have been a way to scare his boss into letting him leave his apprenticeship. If so, it worked. John Lambert, the lawyer he was working for, let him go. His friends and acquaintances gave him money, and Chatterton went to London.

Life in London

Chatterton was already known to readers of the Middlesex Journal as a writer named Decimus, a rival to Junius. He had also written for Hamilton's Town and Country Magazine. He quickly found places to publish his work in other political magazines that supported John Wilkes and freedom. His writings were accepted, but the editors paid him very little or nothing.

He wrote hopeful letters to his mother and sister. He spent his first earnings on buying gifts for them. Wilkes had noticed his sharp writing style and wanted to meet the author. Lord Mayor William Beckford politely thanked him for a political letter and greeted him kindly. Chatterton was very disciplined and hardworking. He could write like Junius or Tobias Smollett. He could also imitate the sharp humor of Charles Churchill. He could even make fun of James Macpherson's Ossian or write with the elegant style of Alexander Pope or Thomas Gray.

He wrote political letters, poems about country life (eclogues), songs, operas, and satirical pieces, both in prose and poetry. In June 1770, after nine weeks in London, he moved from Shoreditch, where he had stayed with a relative. He moved to an attic room in Brook Street, Holborn. He was still very short on money. Also, the government was now prosecuting newspapers for certain types of political letters, so he couldn't write in the Junius style anymore. This forced him to write lighter pieces. In Shoreditch, he had shared a room. But now, for the first time, he had complete privacy. His roommate in Shoreditch had noticed that Chatterton spent much of the night writing. Now, he could write all night long. His love for old stories came back. He copied his "Excelente Balade of Charitie" from an imaginary old parchment by the priest Rowley. He sent this poem, written in old-fashioned language, to the editor of the Town and Country Magazine, but it was rejected.

Mr. Cross, a nearby apothecary (like a pharmacist), often invited him to dinner. But Chatterton refused. His landlady also suspected he was hungry and urged him to share her dinner, but he wouldn't. She later said she knew he hadn't eaten for two or three days. But he told her he wasn't hungry. A note found in his pocket-book after his death showed how little he had earned. Editors like Hamilton and Fell, who had praised him so much, paid him only about a shilling for an article and less than eightpence for his songs. Many accepted pieces were held back and never paid for. According to his foster-mother, he had wanted to study medicine with Barrett. In his desperation, he wrote to Barrett asking for a letter to help him get a job as a surgeon's assistant on a ship.

Death

In August 1770, while walking in St Pancras Churchyard, Chatterton was deep in thought. He didn't see a newly dug open grave in his path and fell into it. His walking companion helped him out and joked that he was happy to help with the "resurrection of genius." Chatterton replied, "My dear friend, I have been at war with the grave for some time now." Chatterton died three days later. On August 24, 1770, he went to his attic room in Brook Street for the last time. He took a poison and tore up his writings. He was 17 years and nine months old.

A few days later, a Dr. Thomas Fry came to London. He wanted to give financial help to the young boy, whether he was the "discoverer" of the poems or the "author." Dr. Fry found a piece of paper, likely one of the last things Chatterton wrote, among the torn papers on the floor of his attic. This fragment was part of the ending of Chatterton's play Aella. It is now kept at the Bristol Public Library and Art Gallery.

Remembering Thomas Chatterton

Chatterton's death didn't get much attention at the time. The few people who appreciated the Rowley poems thought he had just copied them. He was buried in a graveyard next to the Shoe Lane Workhouse in London. There's a story, though not proven, that his uncle secretly moved his body and buried it in Redcliffe Churchyard. A monument has been built there to remember him. It has a fitting message from his own "Will": "To the memory of Thomas Chatterton. Reader! judge not. If thou art a Christian, believe that he shall be judged by a Superior Power. To that Power only is he now answerable."

The big debate about his work started after Chatterton's death. A book called Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century (1777) was put together by Thomas Tyrwhitt. He was a scholar of Chaucer and believed the poems were truly medieval. However, a later edition of the book in 1778 admitted they were probably Chatterton's own work.

Over time, it became clear that Chatterton had written all the Rowley poems himself. Experts studied the language and style, confirming this. Many of Chatterton's original writings are now kept at the British Museum and the Bristol library.

|

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Chatterton para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Chatterton para niños

- List of 18th-century British working-class writers

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |