St Mary Redcliffe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Mary Redcliffe |

|

|---|---|

| Church of St Mary the Virgin | |

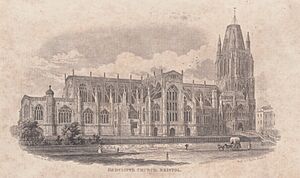

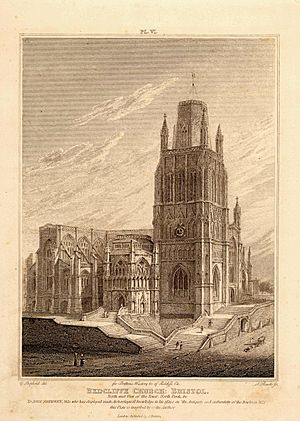

St Mary Redcliffe from the north west, showing tower, spire, nave and hexagonal porch

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Redcliffe, Bristol, England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Broad Church |

| Website | https://www.stmaryredcliffe.co.uk |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 1158 |

| Dedication | Mary, Mother of Jesus |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 8 January 1959 |

| Style | Early English Gothic, Decorated Gothic, Perpendicular Gothic, Gothic Revival |

| Years built | 1185-1872 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 250 feet (76 m) |

| Nave height | 55 feet (17 m) |

| Spire height |

|

| Bells | 15 (ring of twelve plus extra treble, flat sixth and service bell) |

| Tenor bell weight | 50 long cwt 2 qr 21 lb (5,677 lb or 2,575 kg) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | St Mary Redcliffe with Temple Bristol and St John the Baptist, Bedminster |

| Deanery | Bristol South |

| Archdeaconry | Bristol |

| Diocese | Bristol |

| Province | Canterbury |

The Church of St Mary the Virgin, known to many as St Mary Redcliffe, is a very important Church of England parish church in the Redcliffe area of Bristol, England. People first mentioned a church here in 1158. The building you see today was built between 1185 and 1872.

This church is thought to be one of the most beautiful and largest parish churches in the country. It is also a fantastic example of English Gothic architecture. It is so big that some visitors even mistake it for Bristol Cathedral! The church has a special "Grade I listed" status from Historic England, which is the highest possible rating.

St Mary Redcliffe is famous for its many large stained glass windows and amazing stone vaults (curved ceilings). It also has unique flying buttresses (supports on the outside) and a rare six-sided porch. Its huge Gothic spire reaches 274 feet (84 m) to the top of its weathervane. This makes it the second-tallest building in Bristol and the sixth-tallest parish church in England. The spire is a major landmark you can see from all over the city.

Many famous people have praised St Mary Redcliffe. In 1541, John Leland, a writer who explored England, called it "the most beautiful of all churches" he had ever seen. Queen Elizabeth I visited in 1574 and supposedly said it was "The fairest, goodliest and most famous parish church in England." King Charles I also called it "one of the moste famous absolute fayrest and goodliest parish churches within the Realm of England" in 1628.

Simon Jenkins, a church expert, gave St Mary Redcliffe the highest five-star rating in his book England's Thousand Best Churches. He called it a "masterpiece of English Gothic."

History of the Church

How the Church Got its Name

Some people believe a church stood here even in Saxon times. However, no church is mentioned in the Domesday Book from 1086. This means if one existed, it was gone by then. The first official mention of a church in Redcliffe was in 1158. This was in a document signed by King Henry II. It confirmed that churches in Redcliffe and Bedminster belonged to Old Sarum Cathedral. This suggests a church was already in Redcliffe by 1158.

The name "Redcliffe" comes from the church's location. It sits on a striking red sandstone cliff above the River Avon. This area was once home to the Port of Bristol. Rich merchants from the city paid for the original church. Some of these merchants might have even sailed to North America before Christopher Columbus! Today, the main Port of Bristol is further away. But the old quayside, called Redcliffe Quay, still exists near the church. You can still see parts of the red cliff there.

Building the Gothic Church

In 1185, a new north porch was built. It was in the Early English Gothic style, similar to parts of Canterbury Cathedral. This made it one of England's earliest Gothic buildings. Records show repairs in 1207, 1229, and 1230. But the next big building work started much later, at the end of the 13th century.

In 1292, Simon de Burton, who was the mayor of Bristol, started building the church we see today. This big project began in 1294. Workers built the huge base of the northwest tower and part of the west wall. Construction stopped until 1320. Then, the rest of the church was rebuilt in the Decorated Gothic style. The earliest part of this phase was the very unusual hexagonal (six-sided) north porch. It was built next to the older 1185 porch in 1325. So, the church ended up with an inner (1185) and an outer (1325) north porch.

No one knows for sure why the outer north porch is hexagonal. Historians have different ideas. Some think it was inspired by the Chapter House and Lady Chapel at nearby Wells Cathedral. These were built from 1310 onwards. Another idea is that it was influenced by Chinese and Islamic art and architecture. Bristol's port was very important then, with ships traveling far. Islamic buildings often use many-sided shapes.

Around 1330, the south porch and nave aisle were rebuilt in the Decorated style. But they also showed signs of the Perpendicular Gothic style, which became popular later. Influences from Wells Cathedral can be seen again, especially in the south porch, built in 1335. Building continued with the tower and spire in the early 14th century. Then came the south transept and the Lady Chapel, which was finished in 1385.

Historians notice a change in building style between the north and south transepts (the arms of the cross shape) and the choir and nave. The choir was likely finished before the Black Death in 1348. The north transept looks similar to the south. But its inside features show that the Perpendicular style had taken over from the Decorated style. This is most clear in the clerestory (the upper part of the walls with windows).

The 15th Century Changes

Finishing the nave (the main part of the church where people sit) was the biggest job at the start of the 15th century. The nave walls look similar to the choir's. But the ceiling vaults inside are different, suggesting they were built later. Work on the nave continued until 1445 or 1446. Then, the spire fell.

The exact year is not certain, but the top two-thirds of the spire were hit by lightning. This caused it to collapse. St Mary Redcliffe was left with a short, stump-like spire. It looked similar to St Mary's Church in nearby Yatton.

It is not known if the falling spire caused other damage. However, records from 1480 by William Worcestre say: "the height of the tower of Redcliffe contains 300 feet, of which 100 feet have been thrown down by lightning". The spire was not rebuilt right away. Instead, work continued on the nave, which was finished around 1480. The Canynges family, who had helped rebuild the church since the early 14th century, paid for much of this work.

The last major change to the church in the Gothic period was an extension to the Lady Chapel in 1494. Sir John Juyn, a rich lawyer, paid for this. Even though it was built over 100 years after the chapel was first finished, the new part matched the original design perfectly.

The 16th and 17th Centuries

Like many churches in England, St Mary Redcliffe suffered damage to its inside during the 16th and 17th centuries. In 1547, the chantry chapels (small chapels for prayers) were closed down. The crown took away valuable items like plates, lamps, and special clothing. The rood screen (a screen separating the nave from the choir) was destroyed in 1548.

Queen Elizabeth I visited St Mary Redcliffe several times starting in 1574. She is said to have called it "the fairest, goodliest and most famous parish church in England." She made more visits in 1588 and 1591. During these visits, she returned some of the money that had been taken by earlier rulers.

More serious damage happened during the 17th century. From 1649 to 1660, when Oliver Cromwell was in charge, parts of the church were damaged. The pinnacles (small towers on the roof) were removed, decorations were destroyed, the organ was broken, and much of the stained glass was smashed by artillery fire. This kind of damage happened to many churches across the country. Removing the pinnacles made parts of the building unstable. The flying buttresses, which support the walls and ceiling, were also affected. The east window was even bricked up to try and stop the choir walls from collapsing.

Modern History of the Church

18th and 19th Centuries

In 1763, the chapel of the Holy Spirit and the Churchyard Cross were both taken down. The chapel of the Holy Spirit was a separate building built in the mid-13th century. It was used as the parish church while the main building was being constructed. Queen Elizabeth later gave it to the people to use as a grammar school, but it eventually fell out of use. Its demolition finished in 1766.

The church underwent major restoration in the late 19th century. People were worried about the building, which had suffered from years of neglect. In 1842, a group called the Canynges Society was formed to restore the church to its original look. As part of this work, the east window was unblocked and filled with new glass. Old pews and galleries from the Georgian era were removed, and the stonework was repaired. The final step was rebuilding the spire. It had been a stump since it was hit by lightning in 1445 or 1446. The spire was rebuilt to its full height. The Mayor of Bristol placed the capstone on top on May 9, 1872. This was over 260 feet (79 m) above the ground. This work cost a lot of money, and architect George Godwin designed and oversaw it.

20th Century

In 1912, a highly praised organ by Harrison & Harrison was built and installed. It replaced older organs. From 1939 to 1941, a new underground room (undercroft) was built in the Gothic style beneath the north porch. It was meant to be a treasury.

During the Second World War, the church was mostly safe from bombs, even though it was a big target. Watchmen were on the roof at night to put out incendiary bombs. The church's bells and other treasures were stored under the floor in sandbags from 1941 to 1944. There was some minor damage to the organs and roofs, and the upper north porch room was burned out.

The church came very close to serious damage on Good Friday in 1941. A bomb dropped nearby, sending shrapnel, including a large piece of tram rail, into the churchyard. This tram rail is still there today, partly stuck in the ground. It reminds people how close the church came to being destroyed.

In the 1960s, new, colorful stained glass windows were put in the Lady Chapel. They were designed by Harry Stammers. At the same time, a lot of money was spent cleaning the outside stonework, which had become dark from 150 years of pollution.

21st Century

The 21st century has seen much more restoration work on the outside stonework, with a lot of it being cleaned. The organ has also been greatly restored by its original builders. In June 2020, some stained glass that honored the Royal African Company was removed. This happened after the statue of Edward Colston was taken down on June 7. The roofs of the south nave aisle and Lady Chapel have also been repaired.

A project is underway to celebrate the 450th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth I's visit in 2024. The goal is to make the church better for tourists, events, and the community. In 2016, a competition was held to design a new welcome center. The firm Purcell won the contract. Part of the plan includes making Redcliffe Way, the busy road next to the church, more pedestrian-friendly. As of 2023, Purcell is no longer working on the project. Hall McKnight architects have taken over, but no construction has started yet.

Church Design

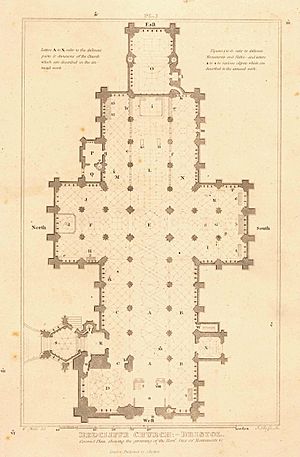

Layout of the Church

The church has a traditional cruciform (cross-shaped) layout. It has a northwest tower, a nave (main seating area), transepts (the arms of the cross), and a chancel (area around the altar). This is common for many parish churches in England. However, St Mary Redcliffe is more like a cathedral in its design. It has aisles (walkways) along all four arms of the church. It also has a Lady Chapel to the east and two porches. Other large parish churches with similar layouts include Beverley Minster and Selby Abbey. But St Mary Redcliffe is special because of its double north porch. It has both an inner and outer room, with the outer one being a rare polygonal (many-sided) shape.

The church is so large that it is a main landmark in Bristol. It is also one of the biggest parish churches in the country. The building is 250 feet (76 m) long from east to west. It is 117 feet (36 m) across the transepts from north to south. This gives it a total area of 20,620 square feet (1,916 square metres). Its size makes it one of the largest churches in England, not counting cathedrals.

Outside of the Church

The Tower

The most striking part of the church's outside is its highly decorated and impressive northwest tower. It is topped by a very tall and thin spire. The oldest parts of the tower, the lowest section, date from around 1294. This part was added to the church that began in 1185. It was built on a huge scale, with walls 7 feet (2.1 m) thick and 35 feet (11 m) long. This lowest section is 34 feet (10 m) high. It has a seven-bay niche-filled arcade with fourteen statues. These statues were added during the 19th-century restoration. Below this arcade are two large windows, one on the north side and one on the west. They are framed by massive buttresses (supports). This lowest part of the tower sticks out into the north porch. The 1325 hexagonal outer porch was built around one of the tower's buttresses.

The second section of the tower is very fancy. It is almost as tall as the section below it, about 33 feet (10 m) high. This second section was started in the early 14th century. So, it shows a later style of architecture. This part of the tower, which holds the ringing room, has a large blind arcade (a row of arches that are not open). It goes all the way around the tower. It has three arches with Y-shaped tracery (stone patterns) in gabled hoods. These contain 19th-century statues of the Apostles. Each arch has detailed carvings of cabbage roses and daisy-like flowers. The middle arch on the east, north, and west sides has a large window. The south side is blocked by the nave.

The third and highest section of the tower holds the bells. It is similar in age to the second section, built in the Perpendicular Gothic style. This section is about 44 feet (13 m) high. It has three huge louvred openings for the bells. These openings take up almost the entire width and height of each wall. This shows the tall, vertical style common in the late Gothic period. These windows have five-lobed (cinque-foil) headed lights. They are separated by thin blind arches, all with many crockets (leaf-like decorations). The buttresses that started on the lowest section end here with crocketed pyramids. The third section is topped by a stone parapet (a low wall) with open triangles and gargoyles. Octagonal pinnacles rise from it. The parapet of the tower is 111 feet (34 m) above the ground. The corner pinnacles reach 139 feet (42 m) high.

The Spire

The first spire on the tower was finished around 1335. It stood for just over 110 years. Then, a storm in either 1445 or 1446 badly damaged it, knocking down the upper part. We don't know exactly how much of the spire was left. Records from 1478 say "the height of the tower at Redcliffe measures 300 feet, of which 100 feet have been thrown down by lightning." But pictures from the 19th century show the tower with a short stump, suggesting it was either taken down or made even shorter. The tallest medieval part of the current spire is 139 feet (42 m) above the ground. This matches how the church looked in the 19th century.

As part of the 19th-century restoration by George Godwin, the spire was rebuilt from 1870 to 1872. Godwin's design was simpler than earlier plans. It was inspired by the spire at Salisbury Cathedral. This is interesting because Redcliffe's original spire might have inspired Salisbury's. The spire stands 152 feet (46 m) tall on top of the tower. This makes its total height to the capstone 262 feet (80 m). With the weathervane, it reaches 274 feet (84 m). The spire's height is often wrongly said to be 292 feet (89 m). This number comes from an old book that included the deep foundations. This mistake has often led people to say St Mary Redcliffe is the third tallest parish church in England.

While the spire is very large, the church is not the third tallest parish church in England. It is the 15th-tallest church in the United Kingdom. It is the 6th-tallest parish church. It is also the second tallest church in South West England, only shorter than Salisbury Cathedral.

The North Porch

The north porch at St Mary Redcliffe has two parts. There is an older inner porch from the 12th century and a more detailed outer porch from the 14th century. The outer porch is the only one you can see from the outside. It dates from around 1325. This outer porch is one of the most famous parts of the church. It is one of only three medieval hexagonal (six-sided) porches in England. The outside has huge five-sided turret buttresses (supports) with square pinnacles that go up the full height of the porch.

The outer porch has three sections of different heights. The lowest section has the main doorway. It has a seven-pointed, double-edged entrance arch. Writer Simon Jenkins called this feature "astonishing." The arch is inspired by Eastern architecture. It has very detailed carvings of seaweed foliage. The second section has a large row of four blind arcades (arches that are not open). These are filled with niches that hold 19th-century copies of the original statues. Above these are large four-light windows. The upper section contains the Chatterton Room. This is a low room lit by rows of mullion windows (windows divided by vertical bars). The parapet (low wall) has open four-leaf shapes (quatrefoils). You can reach it by an octagonal stair turret in the southeast corner.

The main part of the church was mostly built in the late Decorated and early Perpendicular Gothic periods (mid-14th century). Because of this, it has a very consistent style throughout. The aisles (walkways) all have blind quatrefoil parapets (low walls with four-leaf shapes). These are divided by buttresses, from which rise crocketed pinnacles (decorated small towers) and four-light Decorated windows. The clerestory (upper wall with windows) of the main part is supported by large flying buttresses. These buttresses spring from the aisle buttresses. Between each buttress are very large six-light windows. They fill almost the entire space of the clerestory wall. The upper walls also have an open parapet made of open-pointed triangles. Thin, crocketed pinnacles rise above these.

The south and north transepts (the arms of the cross shape) are unusual because they have double aisles. This is rarely seen outside of cathedrals. Each transept is three bays long. The two transepts are slightly different in design. The north transept is a slightly later copy of the 1335 south transept. The south transept has gabled buttresses for the aisles and flying buttresses for the clerestory. The clerestory windows are smaller than those in the main part of the church. They have a different design, with a central arch of three lights surrounded by glazed quatrefoils. The north transept looks more like the nave and chancel, with the same clerestory window design.

The chancel (the area around the altar) continues the same design as the nave. However, the north aisle is partly blocked by the two-bay organ chamber. This chamber has windows with vertical bars (mullions) and three-lobed (trefoiled) tops, and a wide chimney. East of the chancel is the two-bay Lady Chapel. It was built in two sections: first around 1385, and then extended in 1494. The chapel has a large five-light window in its westernmost section, from the earlier building period. It has a smaller four-light window in the eastern section. The eastern gable (triangular wall) of the chapel has a wide but low six-light Perpendicular window.

All four arms of the church have large or very large windows at their ends. The west window is tall and has five lights. It is divided into two levels by transoms (horizontal bars). It features five-lobed crosses. The north and south transept ends have "immensely tall" four-light windows. These are divided into three levels by two rows of transoms. They feature Y-tracery and net-like tracery in the arch tops. The chancel end is almost entirely filled by a large seven-light window with an alternating tracery design.

Inside the Church

Amazing Vaults

One special thing about St Mary Redcliffe is that its entire ceiling is made of stone vaults. No other parish church in England has a medieval stone vault throughout the whole building. The oldest vault is in the inner north porch, from around 1185. It is a simple ribbed vault, like the one at Durham Cathedral. The outer porch, built around 1325, has a much fancier hexagonal vault that looks like a six-sided star.

The main part of the church has ceilings mostly made of lierne vaults. These have different rib designs, like lozenges in the nave, hexagons in the south aisle, squares in the transepts, and rectangles in the choir. These are made by different combinations of ribs crossing each other, forming what Simon Jenkins called "an astonishing maze." The nave vaulting has over a thousand carved and gilded bosses (decorative carvings where ribs meet). These bosses show different scenes and objects, including saints, Bible stories, and people who helped build the church.

There are two other notable vaults. One is the star vault of the Lady Chapel from the late 14th century. The other is the five-sided star vault under the tower. An archaeological study dates this one to the late 1460s or early 1470s. Most of the vaults were repainted in the 1980s and 1990s. They have bright colors like green, gold, blue, and red.

Beautiful Stained Glass

The church lost most of its medieval stained glass during the damage caused by Parliamentary forces in the 17th century. Only small pieces remain in the north transept, St John's chapel, and lower tower windows. In 1842, the committee restoring the church wanted to fill the large east window with glass, which was bricked up at the time. In 1847, they hired William Wailes to design it. This window was later replaced in 1904 by a design from Clayton and Bell. Clayton and Bell provided much of the stained glass for the church after 1842.

A notable medieval window that survived is in the lowest part of the tower. It shows eight large figures, including Archbishop Thomas Becket and saints like Lawrence and John the Baptist. This window was restored in the 19th century. During the Second World War, bombs damaged the Lady Chapel windows. These were replaced by five colorful windows designed by Harry Stammers from 1960 to 1965. In 2020, after the statue of Edward Colston was taken down, the church decided to remove the lower four panels in the main north transept window that honored him. They were temporarily replaced with clear glass. A competition to design new panels was launched in May 2022. In September 2022, Ealish Swift, a junior doctor, won. Her designs show the Middle Passage, the Bristol bus boycott, and the Refugee Crisis.

As of 2023, the church has a mix of stained glass and clear glass. Most of the Victorian work is in the east end, and the nave's clerestory windows have clear glass.

Inside Decorations and Memorials

The church has many monuments and memorials. This is because of its long connection to Bristol, its port, and Queen Elizabeth I. Important items inside include a beautiful iron screen designed by William Edney in 1710. It was meant to separate the chancel and nave but was moved under the tower during restoration. There is also a Victorian reredos (a screen behind the altar) below the east window. Other notable items are the 19th-century pews, the 15th-century St John's font (a baptismal basin), and the 15th-century choir stalls. The font is the only thing left from St John's Church in Bedminster after the Blitz.

The church also has many memorials. The most famous is the brightly colored tomb of William Canynges in the south transept. There is also a memorial to Queen Elizabeth I. Other monuments include a model of a ship that sailed from Bristol's port. There is a wall memorial for Admiral Sir William Penn, the father of William Penn who founded Pennsylvania. His helmet and armor hang on the wall, along with torn flags from Dutch ships he captured. The church also displays a rib from a whale brought back by John Cabot from one of his voyages. You can also see a carved medieval cope chest (for church robes), a wineglass-shaped pulpit, and many misericords (small ledges on choir stalls).

Music at the Church

The Organ

The first record of an organ at St Mary Redcliffe is from 1726. A new organ by John Harris and John Byfield was installed. This organ was one of the largest of its time. It had three manuals (keyboards) and 26 stops (sets of pipes). It was located on a new gallery in the nave. This organ was rebuilt in 1829 and then completely changed in 1867. It was made larger and moved to the chancel. The 1867 organ still had three manuals but more stops, 33 in total.

From 1910 to 1912, organ builders Harrison & Harrison built and installed a brand new organ. They used a small amount of the old pipes. The new organ was much larger. Because of space, it had to be split between the north and south walls of the chancel. A new stone room for the Swell Organ was built. The Great Organ was placed on the north side of the chancel, with other parts on the south. The console (where the organist plays) was placed near the north transept. This organ had more than twice as many stops as the previous ones, with 68 stops when installed.

In 1941, the Swell Organ was damaged by fire and bombs. It had to be rebuilt in 1947 with extra pipes. The organ was cleaned and repaired in 1974 and 1990. It also got new equipment and more stops, while two stops were removed. The 1990 work was not fully satisfactory. So, when the organ was due for its next restoration in the early 2000s, part of the project was to fix those earlier issues.

The project to restore the organ for its 100th birthday started in 2007. The goal was to raise about £800,000. Half the money came from the Canynges Society. The other half was raised by the church community, including a £100,000 donation left anonymously. The organ was taken apart in 2009 and put back together in 2010. It received four new blowers, a new layout for the swell, new actions for the keyboards, and was cleaned and tuned. Today, the organ has 71 stops and 4,327 pipes. This makes it one of the largest organs in Southern England. The organ is highly regarded for its sound quality, considered among the best in the country.

In 2024, there were plans for churches in Britain, including St Mary Redcliffe, to hold concerts with doom metal bands and organ. This style is called "organic metal." The director of music at St Mary Redcliffe said, "Our organ is world-famous – Handel played it. ... There's a lot of history, so by doing something like a rock concert with an organ follows on in that kind of tradition."

The Bells

Early Bells

The first record of bells at Redcliffe is from 1480. There was a very large set of six bells. The people who made them are not known. In 1572, the 4th bell was recast (melted down and reshaped). In 1622, the 5th and 6th bells were recast by Roger Purdue. The Purdue family were famous bell makers in England. Many of their bells still exist today. In 1626, the bells were rehung in a large oak frame.

In 1698, Abel Rudhall added two new smaller bells, making a total of eight. In 1763, Thomas Bilbie recast four of the eight bells. The Bilbie family was another well-known bell foundry. The first full peal (a long sequence of bell changes) in the tower happened on May 29, 1768.

19th Century Additions

In 1823, two more smaller bells were added, making ten bells in total. The bells were increased to twelve in 1872. This made them the third set of twelve bells in the West Country. By the late 1880s, the bells were becoming hard to ring. Experts from John Taylor & Co inspected them. They found that the fittings of the 10th and tenor bells were in bad shape. They also said the frame was not strong enough for such heavy bells. They suggested improvements, including adding iron supports.

The first full peal on the ring of twelve bells was on New Year's Eve 1899. It was a very fast peal, which caused a big debate among bell ringers. Many thought it was "impossibly fast" given how heavy the tenor bell was thought to be.

20th Century Restoration

In 1902, the experts from Taylor's came again. They found things were much worse. Some of the frame timbers were rotting. They advised that the bells should be rehung in a new metal frame. All twelve bells would be on one level. They also recommended new fittings. The church decided to recast the lightest seven bells and the tenor bell. The other four bells would be retuned.

The bells and frame left Bristol for Loughborough in early 1903. When the bells arrived, the tenor bell was found to be much lighter than people thought. This explained how the 1899 peal was so fast. The lightest seven and the tenor bell were melted down and recast with more metal. The 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th bells had their canons (loops for hanging) removed and were retuned. This made them lighter.

The 9th bell was recast again later that year for an unknown reason. Legend says the railway company dropped it on the way back to Bristol. The bells received all new fittings. They were hung in a massive new cast iron frame for 12 bells in late 1903. There was even space left for a 13th bell later.

When the bells were installed, the new, heavier tenor bell made them the fourth heaviest set of bells in the world for change ringing. They were the second heaviest set of twelve bells. The first full peal on the new bells was on New Year's Day in 1904. The bells were later surpassed by others and are now the sixth heaviest set of bells in the world. They are also the heaviest set of bells in any parish church.

In 1933, Taylor's rehung the bells on new ball bearings. These new bearings did not need regular greasing like the old ones.

Bells Since World War II

In spring 1941, after many towers in London were bombed, the church removed the bells from the tower. They were kept safe in the undercroft under sandbags. The bells were returned to the tower and rehung in November 1944.

In 1951, the 13th bell that Taylor's had left space for was ordered. This bell, called a flat sixth, was placed between the sixth and seventh bells. It allows for a lighter set of eight bells to be rung. This makes it easier to teach new bell ringers.

In 1967, St John's Church in Bedminster was demolished. Its only surviving bell was given to Redcliffe. This increased the number of bells to fourteen. This bell was recast in 1969 to better match the Redcliffe bells. This 14th bell, called an 'extra treble,' was hung in a new frame above the existing thirteen bells.

After the bells' 100th birthday in 2003, they received more attention. In 2009, the 9th bell was rehung with a new, larger wheel to make it easier to ring. In 2012, the 8th bell, cast in 1763, was replaced. It was too light and didn't sound good with the newer bells. A new bell was cast to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. It was much heavier than the old one and was hung in spring 2013. The old 8th bell was hung above the main bells for chiming. The last major work on the bells was in 2017. Their fittings and frame were repainted. The bells remain one of the finest sets in existence. Bell ringers from all over the world come to ring them. Over 300 full peals have been rung on the bells since 1768. The St Mary Redcliffe Guild of Ringers rings several full peals each year, often for national events.

Location and Surroundings

Since the building of Redcliffe Way in the 1960s, the church sits next to a busy road on its north side. This road's construction led to many historic buildings facing the church being torn down. It also caused the stone to gradually darken from pollution. However, the church has kept its historic south churchyard. This area has been called a "cathedral close in miniature." It has a small group of listed buildings around a south-facing lawn. These buildings include a row of terraced houses built from 1760 to 1762. All of them are Grade II listed.

The south churchyard has the Redcliffe War Memorial. It is a large stone pillar topped by a cross. It was designed in 1921 to remember those who died in the First World War. It was later changed to include those lost in the Second World War. The memorial is Grade II listed. Two other parts of the churchyard are also listed: the walls on Colston Parade from the 18th century, and the balustrade (a row of small pillars) around the west front. Both are Grade II listed.

The churchyard also contains the Redcliffe Pipe. This was a water pipe given by Robert de Berkeley in 1190 to bring fresh water to the church. He allowed a 2514-meter (8248 ft) long pipe to be built from Knowle Hill to St Mary Redcliffe. A yearly walk along the pipe's route still happens today. The pipe was damaged in the Bristol Blitz. The current pipe ends near the balustrade in front of the west front. It has a brass drinking fountain from 1823, but the water from the pipe does not actually go into the fountain.

See also

- Churches in Bristol

- Grade I listed buildings in Bristol

- List of tallest buildings and structures in Bristol

- List of tallest church buildings in the United Kingdom

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |