Treaty of London (1700) facts for kids

| Second Treaty of Partition between England, France and the Dutch Republic | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Context | Voiding of Treaty of The Hague (1698) due to the death of Joseph Ferdinand in February 1699 |

| Signed | 24 March 1700 |

| Location | London and The Hague |

| Parties | |

The Treaty of London (1700), also known as the Second Partition Treaty, was an agreement made by King Louis XIV of France and William III of England. They wanted to find a peaceful solution for who would become the next ruler of the Spanish Empire. This was a big problem that later led to a major war called the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714).

Both kings decided to divide the Spanish Empire without asking Spain first. The Spanish people, however, believed their empire should stay together. Because of this, many historians think the treaty was almost impossible to enforce.

Charles II of Spain became king in 1665 when he was only five years old. He was often sick and had no children, even though he married twice. By 1698, it was clear he would die without an heir. This left a huge question about who would rule Spain next. The Spanish Empire was still very powerful around the world. The closest relatives who could become king were from the Austrian Habsburg family and the French Bourbon family. If either of these families took over Spain, it would greatly change the balance of power in Europe.

To avoid another expensive war like the Nine Years' War, William and Louis signed the Treaty of The Hague (1698) in 1698. This was called the First Partition Treaty. It named Joseph Ferdinand of Bavaria as the heir to the Spanish throne. But Joseph Ferdinand died from smallpox in February 1699. This meant a new plan was needed. The Treaty of London then named Archduke Charles, a younger son of Emperor Leopold I, as the new heir. However, this treaty also failed to stop the war, which began in July 1701.

Contents

Why the Treaty Was Needed

In 1665, Charles II of Spain became the last ruler of Habsburg Spain when he was just five years old. He was often ill throughout his life. Even though he married twice, it seemed by 1698 that he would die without any children.

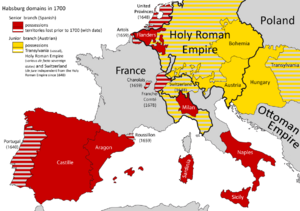

Spain's money and military power had become weaker in the 1600s. However, the Spanish Empire was still very large. It included lands in Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, the Philippines, and the Americas. The closest people who could inherit the throne were from the Austrian Habsburg family and the French Bourbon family. Because of this, who would rule Spain was very important for the European balance of power. This topic had been discussed for many years. For example, in 1670, Charles II of England secretly agreed to support the claim of Louis XIV of France.

William III of England hoped the Partition Treaties would help build a lasting peace. He wanted to continue the good relationship he had started with Louis XIV at the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick. But it seemed unlikely that Spain and Austria would accept a solution forced upon them. There was a lot of distrust between the countries that had been fighting almost constantly since 1670.

William made both treaties without telling the English Parliament or his own ministers. This was still common in France but not in England. Lord Somers, who was part of the group managing the English government for William, did not like the First Partition Treaty. He only found out about it shortly before it was signed.

Few of William's ministers in England or the Dutch Republic trusted Louis. This feeling grew stronger when the Marquis d'Harcourt was sent to Madrid in November 1698. His goal was to get Spanish support for a French candidate to the throne. The Spanish did not want their empire divided without their input, just to suit other countries. On November 14, 1698, King Charles announced his will. It named six-year-old Joseph Ferdinand of Bavaria as the heir to an undivided Spanish Empire. This ignored the land changes in the First Partition Treaty. When Joseph Ferdinand died of smallpox in February 1699, a new plan was needed.

How the Treaty Was Negotiated

The Spanish royal court was divided into two groups: one that supported Austria and one that supported France. The French group was led by Cardinal Portocarrero, the Archbishop of Toledo. For much of Charles's rule, the pro-Austrian group was in charge. This group was first led by his mother, Mariana of Austria. After she died in 1696, his second wife, Maria Anna of Neuburg, took over.

Because of their influence, Spain joined the group against France during the Nine Years' War. This turned out to be a very bad decision. By 1696, France held most of Catalonia, a region in Spain. Spain also had to declare bankruptcy in 1692. Even though Maria Anna managed to stay in power with false rumors of her pregnancy, Charles had to send away her German friends.

For different reasons, most of the Spanish nobles did not like the Austrians. King Charles also disliked their proud attitude. He made it clear to the French envoy Harcourt that he would not agree to divide the empire. Many Spanish politicians preferred a French candidate. They thought that France would be a better ally than an enemy, based on the wars of the past 50 years. Also, France's location meant it could protect Spain better than Austria.

After Joseph Ferdinand died, Louis's main foreign policy advisor, the Marquess of Torcy, quickly wrote a new proposal. William agreed to the main ideas in June 1699. However, when the suggested treaty was shown to Emperor Leopold, he first refused the land changes it required. Because of this, the Dutch delayed giving their official agreement. So, the treaty was not formally signed in London until March 12, 1700. It was then signed in The Hague on March 24.

What the Treaty Said

The main change from the First Treaty was who would inherit the Spanish throne. Instead of Joseph Ferdinand, it named Leopold's younger son, Archduke Charles. Spain would keep its empire outside Europe and the Spanish Netherlands. But France would get the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, and the Spanish province of Gipuzkoa. France would also trade the Duchy of Lorraine for the Duchy of Milan.

Then, France would give Naples and Sicily to Victor Amadeus II of Sardinia. In return, France would get the Counties of Nice and Savoy. These were lands in the Savoyard state that later became part of France in 1859.

Even though Leopold agreed in principle to divide the Spanish Empire if his son became king, he did not like France getting Spanish lands in Italy. He especially thought Milan was important for the safety of Austria's southern borders. Also, Lorraine was a state in the Holy Roman Empire. France had taken it in 1670 and only returned it in 1697. The Duke of Lorraine, Leopold, Duke of Lorraine, had just gotten his land back and was Leopold's nephew.

Because of these issues, it was unlikely the treaty's terms would be followed. Neither Leopold nor Victor Amadeus would agree to the land exchanges. And Spain would not accept the idea of dividing its empire at all.

What Happened Next

When the Spanish learned about the Treaty of London in mid-June, King Charles changed his will. He named Archduke Charles as his heir again and said the Spanish monarchy must stay undivided. In September, Charles became sick once more. By September 28, he could no longer eat. It seemed he would die soon. On October 2, Cardinal Portocarrero convinced him to change his will again. This time, he named Philip of Anjou, who was the younger son of Louis, Grand Dauphin and grandson of Louis XIV. Charles died on November 1, 1700, just five days before his 39th birthday.

When Louis received Spain's official offer to Philip on November 9, he had a choice. He could reject it and insist that Archduke Charles take the throne, as the Treaty of London said. If Leopold still refused the land changes, Louis could then ask England and the Dutch Republic to help him enforce the treaty. However, it seems Louis never seriously considered this. As William noted, it made no sense "to go to war...for a treaty I have only made to prevent war." Philip was declared Philip V of Spain on November 16. The War of the Spanish Succession began in July 1701.

The treaty not only failed to stop the war in 1701, but it also showed that kings could no longer simply force their solutions on countries. When the English Parliament finally learned about the treaty's terms in March 1700, they were very angry. They felt the treaty hurt English trade. They were also upset because it had been approved without their knowledge or agreement. The Tory party, which had the most members, later tried to accuse Lord Somers of wrongdoing for his part in the negotiations. While they were not successful, this event made relations between the two parties very bitter. It also had a big impact on British politics for the next twenty years.

See also

In Spanish: Segundo Tratado de Partición para niños

In Spanish: Segundo Tratado de Partición para niños