Trieste (bathyscaphe) facts for kids

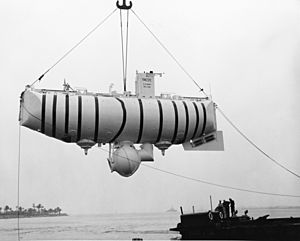

Trieste shortly after her purchase by the US Navy in 1958

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | Trieste |

| Builder | Acciaierie Terni/Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico |

| Launched | 1 August 1953 |

| Fate | Sold to the United States Navy, 1958 |

| Name | Trieste |

| Acquired | 1958 |

| Decommissioned | 1966 |

| Reclassified | DSV-0, 1 June 1971 |

| Status | Preserved as an exhibit in the U.S. Navy Museum |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Bathyscaphe |

| Displacement | 50 long tons (51 Mg) |

| Length | 59 ft 6 in (18.14 m) |

| Beam | 11 ft 6 in (3.51 m) |

| Draft | 18 ft 6 in (5.64 m) |

| Complement | Two |

Trieste was a special deep-diving submarine called a bathyscaphe. It was designed in Switzerland and built in Italy. In 1960, it made history by becoming the first crewed vessel to reach the very bottom of the Mariana Trench. This spot is known as Challenger Deep, the deepest point in Earth's oceans.

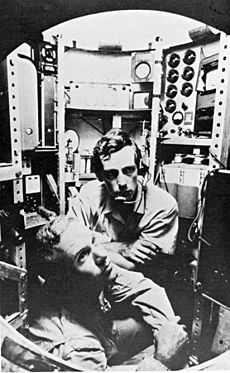

This amazing journey was part of Project Nekton, a series of dives by the United States Navy near Guam. Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and US Navy lieutenant Don Walsh piloted Trieste. They reached an incredible depth of about 10,916 metres (35,814 ft). Trieste is now on display at the National Museum of the United States Navy in Washington, D.C..

Contents

How Trieste Was Designed

Trieste was designed by Swiss scientist Auguste Piccard. He was the father of Jacques Piccard, who piloted the record-breaking dive. A bathyscaphe is a special kind of deep-diving vessel that can move freely underwater. This is different from a bathysphere, which is usually lowered and pulled back up by a cable. The name "bathyscaphe" comes from ancient Greek words meaning "deep boat."

Trieste was built in Italy and launched in 1953. It was first used by the French Navy. In 1958, the United States Navy bought it.

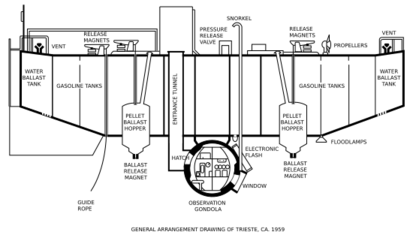

Key Parts of the Bathyscaphe

Trieste had a strong crew sphere where two people could sit. This sphere was attached to a large hull. The hull had tanks filled with gasoline (petrol). Gasoline is lighter than water, so it helped the vessel float. To sink, Trieste used tanks filled with iron shot and water.

The hull was built in the Free Territory of Trieste, which is now part of Italy. This is how the bathyscaphe got its name. The strong crew sphere was built separately and then added to the hull.

The crew sphere was like a small, self-contained room. It had its own air system to keep the crew safe. Oxygen was supplied from tanks, and a special system removed carbon dioxide from the air. Batteries provided all the electrical power needed.

The original crew sphere was made of steel and was about 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) wide. For the deep dive to Challenger Deep, it was replaced with an even stronger one in 1958. This new sphere was made in Germany. It was slightly smaller, about 2.16 metres (7.1 ft) wide, but its walls were much thicker, at 127 millimetres (5.0 in). This made it strong enough to handle the extreme pressure at the bottom of the ocean.

To look outside, the crew used a special window called a porthole. It was made from a thick, tapered block of acrylic glass. This was the only clear material strong enough for such deep pressures. Bright arc-light bulbs lit up the outside. These bulbs could also handle the immense pressure.

The gasoline in the buoyancy tanks helped Trieste float. As the vessel went deeper, seawater could flow in and out of the tanks. This kept the pressure inside the tanks equal to the outside pressure.

To sink, Trieste used iron shot as ballast. There were two large hoppers, one at the front and one at the back of the crew sphere. Each held about 9 metric tons (20,000 pounds) of iron shot. This shot was held in place by electromagnets. To rise, the crew would turn off the electromagnets, releasing the iron shot. This made the bathyscaphe lighter and allowed it to float up.

Water tanks at each end of the hull were used for floating on the surface. They were pumped out to make the vessel lighter for towing. To sink, these tanks were completely filled with water.

After the US Navy bought Trieste, it was changed quite a bit. These changes helped it prepare for the historic dive to Challenger Deep in 1960.

The Mariana Trench Dives

Trieste left San Diego in October 1959. It traveled to Guam to take part in Project Nekton. This project involved a series of very deep dives into the Mariana Trench.

On January 23, 1960, Trieste reached the ocean floor in the Challenger Deep. This was the first time any vessel, with or without a crew, had reached the deepest known point in Earth's oceans. The instruments on board first showed a depth of 11,521 metres (37,799 ft). This was later corrected to 10,916 metres (35,814 ft). More recent measurements show Challenger Deep is between 10,911 metres (35,797 ft) and 10,994 metres (36,070 ft) deep.

The journey down to the ocean floor took 4 hours and 47 minutes. Trieste descended at a speed of about 0.9 metres per second (3.2 km/h; 2.0 mph). When they passed 9,000 metres (30,000 ft), one of the outer windows cracked. This shook the entire vessel, but the main crew sphere remained safe.

Piccard and Walsh spent twenty minutes on the ocean floor. The temperature inside the cabin was 7 °C (45 °F). Surprisingly, they were able to talk to their support ship, USS Wandank (ATA-204). They used a special sonar/hydrophone voice system. Sound travels very fast in water, about five times faster than in air. So, it took about seven seconds for a message to reach the ship and another seven seconds for the answer to return.

While at the bottom, Piccard and Walsh thought they saw some sole and flounder fish. However, scientists later questioned this observation. Most fish cannot survive at such extreme depths. Instead, they might have seen sea cucumbers or other invertebrates. These creatures can live at depths of 10,000 m (33,000 ft) or more. Walsh later said they might have been mistaken because they were not experts in marine biology.

Piccard and Walsh also noted that the ocean floor was covered in "diatomaceous ooze." This is a type of soft mud made from tiny sea organisms. The trip back up to the surface took 3 hours and 15 minutes. In January 2020, the National Museum of the Navy celebrated the 60th anniversary of this historic dive.

Other Deep Dives and Retirement

Before the US Navy bought it, Trieste made many deep dives in the Mediterranean Sea. Between 1953 and 1957, it completed 48 dives deeper than 3,700 metres (12,100 ft).

In 1963, Trieste was changed again. It was then used in the Atlantic Ocean to search for the missing nuclear submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593). In August 1963, Trieste found parts of the wreck. The debris was off the coast of New England, about 2,560 m (8,400 ft) below the surface. Trieste received the Navy Unit Commendation for its important role in this search.

After this mission, Trieste was returned to San Diego and taken out of service in 1966. Between 1964 and 1966, Trieste helped develop its replacement, the Trieste II. The original crew sphere from Trieste was even used in Trieste II. In the early 1980s, Trieste was moved to the Washington Navy Yard. It is now on display at the National Museum of the United States Navy, along with its stronger Krupp pressure sphere.

Awards

- Navy Unit Citation with star

- Meritorious Unit Commendation with star

- Navy E Ribbon

- National Defense Service Medal with star

See also

In Spanish: Batiscafo Trieste para niños

In Spanish: Batiscafo Trieste para niños

- Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle

- Deep Submergence Vehicle

- Alvin (DSV-2)

- Project Mohole

- MIR (submersible)

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |