Wade's Causeway facts for kids

Wade's Causeway, c. 2005

|

|

| Alternative name | Wheeldale Roman Road; Goathland Roman Road; Auld Wife's Trod; The Skivick |

|---|---|

| Location | Egton Parish, North Yorkshire, England |

| Coordinates | 54°22′14″N 0°45′33″W / 54.370575°N 0.759134°W |

| Type | linear monument, possibly road or dike |

| Length | between 1.2 and 25 miles (1.9 and 40.2 km) |

| History | |

| Builder | [disputed] |

| Material | sandstone |

| Founded | [uncertain] |

| Abandoned | [uncertain] |

| Periods | Variously contended to be Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman or Medieval |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1912–1964 (not continuous) |

| Archaeologists | James Patterson, Oxley Grabham, Tempest Anderson, James Rutter, Raymond Hayes, J Ingram, A Precious, P Cook |

| Condition | ruined, overgrown, heavily robbed |

| Ownership | Duchy of Lancaster |

| Management | North York Moors National Park Authority, in cooperation with English Heritage |

| Public access | Yes |

| Reference no. | 1004876 |

| UID | NY 309 |

| National Grid Reference | SE 80680 97870 |

Wade's Causeway is a very old, winding path or structure in the North York Moors national park in North Yorkshire, England. It could be up to 6,000 years old! People aren't sure if it's a road or a boundary wall.

The name "Wade's Causeway" can mean two things. It might refer to a specific stone path about 1 mile (1.6 km) long on Wheeldale Moor. Or, it could mean a much longer structure, possibly up to 25 miles (40 km) long, that includes other ancient sites. The part you can see on Wheeldale Moor is a raised bank of soil, gravel, and stones. It's about 0.7 metres (2.3 ft) high and 4 to 7 metres (13 to 23 ft) wide. Flat stones cover the top, but it's hard to tell its original shape because of weather and human damage.

For hundreds of years, local stories have been told about this structure. People often said a giant named Wade built it. In the 1720s, the causeway was written about, and more people learned about it. Soon, historians became interested. They thought it was a road built by the Romans to cross wet ground. This idea was popular for a long time.

In the early 1900s, a gamekeeper who liked archaeology cleared and dug up the Wheeldale Moor section. A historian named Ivan Margary agreed it was a Roman road. He even gave it a special number in his book about Roman roads. Later, archaeologist Raymond Hayes studied it more in the 1950s and 1960s. His research also suggested it was a Roman road.

However, in recent years, experts have started to question if it really was a Roman road. They have suggested other ideas for what it was and when it was built. In 2012, English Heritage, which helps manage the site, suggested new ways to research the causeway. They hope to solve some of its mysteries.

What is Wade's Causeway?

Where is it and what's it made of?

The Wheeldale structure is mostly found in wild, open moorland covered in heather. Experts believe this area looks much the same as it did in the Bronze Age. Back then, forests were cleared for farming and grazing animals. Wheeldale Moor can get very wet and flood easily, both long ago and today. The ground underneath has layers of sand, gravel, and different kinds of sandstone and limestone.

How was it built?

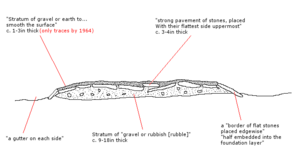

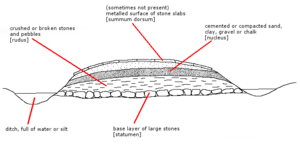

The part of the causeway you can see on Wheeldale Moor has a surface made of flat sandstone slabs fitted closely together. These stones are usually about 45 centimetres (18 in) wide, but some are much bigger. No one knows why there was a raised ridge in the middle of one section.

The stone slabs sit on a curved base of gravel, clay, and other materials. This base forms a raised bank, which is about 3.6 to 7 metres (12 to 23 ft) wide at the top. Some parts of the bank have ditches on either side, making the total width about 5 to 8 metres (16 to 26 ft). The bank rises about 0.4 metres (1.3 ft) above the ground around it.

Experts like Hayes and Rutter think the main reason for this raised bank was to help water drain away from the road. Archaeologist David E Johnston noted that many small culverts (tunnels for water) cross the structure. This helps water flow through the often-boggy ground. This is why it was called a "causeway," which is a raised path across wet land.

Some historians believe that Roman roads were often built on raised banks, even if the ground wasn't wet. They think the name "causeway" for Roman roads might just refer to these banks.

Many experts, including Johnston, Nikolaus Pevsner, and Richard Muir, think the Wheeldale structure once had a gravel surface on top of the stones. Johnston and Pevsner believe the gravel washed away over time. Muir thinks people removed it. Either way, the stones we see today are probably not the original top surface. Old writings from the 1700s and 1800s mention the causeway being "paved with a flint pebble" or having a "stratum of gravel" above the stones. Even in the 1960s, traces of gravel were still visible.

Some experts thought the structure had ditches along its sides, but others, like Hayes, weren't sure if they were part of the original design.

Where can you see it today?

The only part of Wade's Causeway that is still clearly visible is a 1.2 miles (1.9 km) section on Wheeldale Moor. It runs mostly north-northeast and is about 185 to 200 metres (607 to 656 ft) above sea level. You can easily see this part because it has many stones on a raised bank and not much plant growth.

The causeway's path on Wheeldale Moor is mostly straight, but it has several short, straight sections that sometimes change direction. This doesn't seem to be because of the landscape. In 1855, people also reported seeing overgrown parts of the structure in other nearby places.

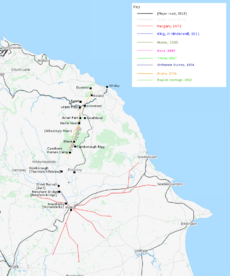

How far did it go?

Many writers believe the structure went much further than the part we see today. However, most of these longer sections are not visible, nor have they been fully dug up or studied. So, there's no clear agreement on its exact full path. The original length of the structure is unknown, but it might have been up to 25 miles (40 km).

To the north

Old records about the causeway's path to the north are very different from each other. Some early maps don't show it, and descriptions vary. One source says you can see a "conjectural" (guessed) northern part in aerial photos. Hayes found a "trace of the embankment" and "a patch of the metalling" (stone surface) in a few spots further north.

Beyond Julian Park, some think the structure continued to a Roman fort called Lease Rigg. This idea comes from old reports that small pieces were visible along this route. Hayes and Rutter seem confident it reached Lease Rigg, but they admit that its path is just a guess for a good part of the way.

Many people have guessed that the structure was a road that went past Lease Rigg all the way to Roman forts or signal stations near Whitby. But this is debated. One old report from 1736 said someone followed its path to the coast. However, it's not clear if they saw the actual structure or just followed a suggested route. Later sources also mention this endpoint, but it's unclear if they visited the site themselves. Many experts say any paths beyond Lease Rigg are "doubtful" and "unproven." Hayes and Rutter found no proof it went further north than Lease Rigg in their 1964 study. Other ideas suggest it went to Goldsborough, Guisborough, or Sandsend Bay.

To the south

Some people also think the structure went south from Wheeldale Moor to connect with the Roman Cawthorne Camp. In the 1900s, English Heritage identified two sections on Flamborough Rigg and Pickering Moor as possible extensions. Hayes said the Flamborough Rigg section was "clearly visible" in 1961. Old maps and other reports seem to confirm the path in this area.

There's even more guessing that the original structure might have gone beyond Cawthorne Camp to a Roman settlement near Malton. Any path further south than Cawthorn is debated. Hayes and Rutter couldn't find any trace of the causeway south of Cawthorn in their 1950s survey.

Beyond Malton, there's a suggested Roman road leading towards York that might be an extension of the causeway. But there's very little proof. One old writer mentioned it in 1736, but later experts couldn't find it.

How do we study this ancient path?

When was it first noticed?

In the 1500s, a historian named John Leland traveled through the area. He mentioned "Waddes Grave" (Wade's Grave) nearby, which was linked to the same myths. But he didn't mention Wade's Causeway itself. This suggests local people didn't point it out to him. In 1586, another historian, William Camden, noted that people in England often thought "Roman fabriks" (buildings) were built by giants. But he didn't name Wade's Causeway specifically.

The first clear written record of the Wheeldale structure was in 1720 by John Warburton. After this, local historians and experts debated what the structure was, where it went, and how old it was. In 1724, a letter mentioned that about 6 miles (9.7 km) of the structure, described as a road, was visible south of Dunsley village.

Francis Drake visited and studied the structure himself, writing about it in 1736. Many other books and reports in the 1800s and 1900s also mentioned the causeway.

Early digs and discoveries

The first recorded digs of the structure happened in the Victorian era. In the 1890s, James Patterson, a gamekeeper at Wheeldale Lodge, started clearing part of the causeway. In 1912, he convinced the government to take care of the 1.2 miles (1.9 km) section on Wheeldale Moor. Patterson, along with others, cleared and dug up this section between 1910 and 1920. Another section near Grosmont Priory was dug up by Hayes between 1936 and 1939.

More recent studies

Historic England's website mentions more small digs in 1946 and 1962. Archaeologist Hayes also did many digs between 1945 and 1950 in several locations. His work was partly paid for by the Council for British Archaeology. He published his findings in a big study called Wade's Causeway in 1964. The year before, the Whitby Naturalists Club surveyed the causeway's path across Wheeldale. English Heritage has also shared records of later surveys done in 1981 and 1984.

The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHME) surveyed the causeway in 1992. Some small digs and analysis happened in 1997 during maintenance work. The most recent survey was an aerial survey in 2010/2011.

What's next for Wade's Causeway?

Professor Pete Wilson has suggested new questions for future research. These include digging to find out when and why it was built. He also suggested looking at old documents for mentions of the monument as a path or in land disputes. Another idea is to use aerial surveys or other remote sensing tools to find out how far the monument extends beyond the parts already dug up.

Newer techniques like optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) testing could also be used. This method can date bricks, pottery, or other fired materials found in the structure. It was successfully used to identify a suspected Roman road in Shropshire.

Who built Wade's Causeway and why?

Since there's no clear proof, people have many different ideas about when Wade's Causeway was built. Dates range from 4,500 BC to around 1485 AD. No coins or other artifacts have been found to help date it. Also, no radiometric surveys have been done. This makes it very hard to figure out an exact date.

So, dating the structure relies on other clues. These include the meaning of its name, how it relates to other nearby structures that are already dated, and comparing its design to known Roman roads.

Was it a Roman road?

Early historians in the 1700s and 1800s didn't believe the old folk tales about giants building the causeway. They were very interested in Roman roads. They thought the Wheeldale structure was built by the Romans in the 1st or 2nd centuries AD. Many believed it connected the Roman Cawthorne Camp in the south to the Roman fort at Lease Rigg in the north. The visible part of the structure does lie roughly between these two sites, which some think supports a Roman origin.

The causeway's average width (about 5.1 metres (17 ft) plus ditches) is similar to other Roman roads. Historian John Bigland wrote in 1812 that only the Romans could have built something of this size and style.

One problem with calling it a Roman road was that old Roman travel guides didn't mention any major Roman roads in this area. In 1817, George Young tried to fix this problem. He argued that one of the Roman routes had been misunderstood and actually passed through Wheeldale. This was possible because the Roman travel guides were lists, not maps. It was hard to match Roman names to modern places.

By the 1900s, the causeway was commonly called the "Wheeldale Roman Road" or "Goathland Roman Road."

The name "Wade's Causeway" also gave some clues. Early 1900s scholar Raymond Chambers thought the name came from Angle and Saxon settlers. They might have named an existing feature after one of their heroes. If the name was given during the Saxon era (around 410 to 1066 AD), then the structure must have been built before then. Hayes and Rutter also thought it was Roman, but for a different reason. They noticed that towns along the causeway didn't have Anglo-Saxon names that usually mean "Roman road." They thought this meant the causeway was already abandoned and not important by the Anglo-Saxon period, probably by 120 AD. So, it must have been built very early by the Romans.

Experts who believed it was a Roman road tried to guess the exact date it was built. They looked at when the Roman military was active in the area. Most Roman roads were built by the military. Many sources think it was built around 80 AD. This was when Gnaeus Julius Agricola, a Roman governor, was trying to expand Roman control in the North York Moors area. He is thought to have ordered the building of the nearby Lease Rigg fort. Other estimates suggest the 4th century AD. This was when Romans might have built roads to defend against new attacks.

Some people, like Michael Dunn, suggested the causeway might have been used to transport jet (a type of black stone) from Whitby. But Hayes and Rutter thought the jet wasn't valuable enough to justify building such a big causeway.

One possible issue with it being Roman is that it has many small bends. Roman military roads are usually straight. However, other known Roman roads also have winding paths, so this isn't a definite sign against it.

Another difference was the use of dressed stone instead of gravel for the surface. Most Roman roads used packed gravel or pebbles. But there are other examples of Roman roads paved with stone blocks, like parts of the Via Appia in Italy. The causeway might have had a gravel surface originally that was removed later. Also, it didn't have a foundation of large stones like some Roman roads. But experts like John Ward say Roman roads varied a lot depending on where they were and what materials were available.

For much of the 1900s, most experts agreed it was a Roman road. Even a 1947 UK government report called it an undoubted Roman road. In 1957, Margary, a top expert, accepted it as Roman. This was the main idea for a long time.

Or was it older, or from the Middle Ages?

In the 1800s, people often thought any well-built old road had to be Roman. But by the late 1900s, archaeologists started looking at other time periods. In 1994, the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England began to review the causeway's age. Air photos of the Cawthorn camps in 1999 didn't show a clear road leading to Wheeldale Moor. Also, the causeway doesn't seem to connect easily to the main Roman road network.

Around the year 2000, some writers started to doubt the Roman road idea. Archaeologists found other raised, stone-covered roads that were built before the Romans came to Britain. This showed that a pre-Roman origin for Wade's Causeway was possible. Several sources from the mid-1990s onward suggested it might be an Iron Age (pre-Roman) road.

Blood and Markham (1992) suggested it might be a road from the medieval period (after the Romans), possibly used for the wool trade. However, this idea doesn't fit well with the theories about how the causeway got its name. English Heritage says it's "quite possible" the causeway was used as a road in medieval times, even if it was built much earlier. Drake recorded in 1736 that the causeway was "not now made use of," but there are no records about its use during the medieval period.

Maybe an ancient boundary wall?

Some people don't think the structure was a road at all. One reason is that several ancient burials (called cists) along the path stick out of its surface by up to 0.4 metres (1.3 ft). This would be very strange for a road. Since 1997, experts, including English Heritage, have considered that it might not be a road.

Archaeological consultant Blaise Vyner suggested in 1997 that it could be the remains of a Neolithic or Bronze Age boundary wall or dike that has fallen apart and had its stones taken. There are other Neolithic remains in the North York Moors, including boundary dikes. Bronze Age sites are also common in the area, making this a possible origin. However, one expert noted in 1912 that the causeway seemed to cut across an older earthwork, meaning it must have been built after that. One idea that could explain many of these puzzles is that dikes in the area were often reused as paths.

In the 2010s, the name "Wheeldale Linear Monument" was used to show that experts weren't sure what its original purpose was. As of 2013, English Heritage said that most experts now think the structure is prehistoric, not Roman. The sign at the end of the Wheeldale section of the structure, where it meets the modern road, shows this uncertainty. The old sign from 1991 said it was a Roman road. But a new sign put up in 1998 admits that its origin and purpose are unknown.

Why is it so hard to tell?

If Wade's Causeway turns out not to be a Roman road, it wouldn't be the only time an ancient structure was wrongly called Roman. A famous example is the Blackstone Edge Long Causeway. It was once thought to be one of the best Roman roads in Britain. Archaeologists Hayes and Rutter, who also thought Wade's Causeway was Roman, agreed. But in 1965, archaeologist James Maxim found a medieval pack-horse trail under Blackstone Edge. This meant the causeway had to be built after the medieval trail. Later research suggested the Blackstone Edge road was probably a turnpike (a road where you pay a fee) from around 1735.

Protecting this ancient mystery

By 1903, the visible part of the causeway on Wheeldale Moor was covered in heather and soil. After being cleared in the 1910s, it was "clear for miles" by 1920. The government then hired someone to keep it clear of plants. But by 1994, the visible section was allowed to be covered by plants again.

Hayes and Rutter said that the parts of the structure beyond Wheeldale Moor are hard to find. This is because they have been badly damaged by natural erosion and by people. Old structures like roads are often "levelled by the plough and plundered of their materials" (meaning farmers plowed over them and people took their stones).

There are specific mentions of damage to the causeway from plowing, cutting down trees, laying water pipes, and even by tracked and armored vehicles in the 1900s. People also took many stones from the structure to build local roads, dry-stone walls, dikes, and farm buildings. This stone stealing happened from 1586 until at least the early 1900s. George Young wrote sadly in 1817 about how the causeway was being destroyed to build a simple field wall.

People's attitudes changed over time, and they started to care more about protecting the structure. In 1913, the Wheeldale structure was legally protected from damage. In 1982, there was a plan to cover most of the exposed section with soil to protect it, but this hasn't happened. Some small repairs were done between 1995 and 1997 to stop water erosion.

There has been at least one report of someone deliberately damaging the structure. But the main concern from visitors is damage from people walking on it. However, not many people visit the site. Also, plants growing back over the surface help protect it. Experts from the North York Moors National Park Authority and English Heritage think natural weathering and grazing sheep cause more damage than people do.

As of 2013, the site is managed by the North York Moors National Park Authority and English Heritage. You can visit the site for free at any reasonable time. About a thousand people visit each month.

Wade's Causeway in stories

Scottish author Michael Scott Rohan used the legend of Wade's Causeway in his Winter of the World trilogy. He also used other English, Germanic, and Norse myths. His books feature a giant named Vayde who ordered a causeway to be built across the marshes.

Other cool ancient sites nearby

English Heritage lists these important historical sites close to Wade's Causeway:

- Cairnfield on Howl Moor: This site has an old settlement, field system, and round burial mounds. (1021293)

- Simon Howe: A round burial mound on Goathland Moor, with two other mounds, a standing stone, and a stone line. (1021297)

- Field system and cairnfield on Lockton High Moor: An old field system and stone piles. (1021234)

- Extensive prehistoric and medieval remains on Levisham Moor: Many old remains from different time periods. (1020820)

- Two sections of Roman road on Flamborough Rigg (1004104)

- Two sections of Roman road on Pickering Moor (1004108)

- Cawthorn Roman forts and camp: Includes a section of a medieval path called the Portergate. (1007988)

- Allan Tofts cairnfield: An old field system, burial mounds, and prehistoric rock art. (1021301)

Old photos of Wade's Causeway

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |