West Coast lumber trade facts for kids

The West Coast lumber trade was a busy shipping route along the United States' West Coast. It mainly carried lumber (wood) from the forests of Northern California, Oregon, and Washington to the big city of San Francisco. Sometimes, these ships also carried other goods from the Pacific Northwest, like salmon. For example, in 1918, a ship called the Henry Wilson sailed from Washington to Australia with a huge amount of lumber and canned salmon.

This trade was super important for starting big shipping companies. One famous example is the Dollar Steamship Company. Its founder, Captain Robert Dollar, came from Scotland and worked in Canadian lumber camps. After moving to San Francisco in 1888, he bought land with lots of trees. Then, he started his own shipping line that even reached China!

Contents

Special Lumber Ships: Schooners

Imagine this: even during the California Gold Rush, lumber for San Francisco had to travel 13,000 miles all the way around Cape Horn from New England! But things began to change. In 1843, Captain Stephen Smith started one of the first lumber mills on the West Coast. It was in a redwood forest near Bodega, California. Another early mill was built by John B. R. Cooper near Forestville, California. By the mid-1880s, there were over 400 mills just in California's Humboldt County!

Building Better Ships

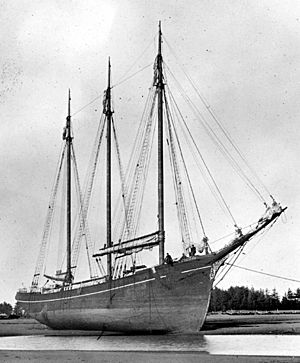

At first, old ships with square sails were used to carry lumber. But these ships were slow, needed many sailors, and were hard to load. So, local shipyards started building special ships just for lumber. In 1865, Hans Ditlev Bendixsen opened one of these shipyards in Fairhaven, California. He built many ships for the lumber trade, including the famous C.A. Thayer, which you can still see today at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. Between 1869 and 1901, he built 92 sailing vessels, including 35 with three masts.

How Lumber Schooners Were Designed

These special lumber schooners were often built from the same strong Douglas fir wood that they carried. (The schooner Oregon Pine was even named after the tree!) They had flat bottoms, which helped them cross shallow sandbars at the entrances of coastal ports. Their decks were kept clear and open, making it easy to load the long pieces of lumber.

Many West Coast lumber schooners were also built without topsails (the highest sails). This design was called "baldheaded." It made it easier for them to sail against the strong westerly winds when heading north. Sailors liked baldheaded ships because they didn't have to climb high masts to adjust the sails. If they needed more speed, they could just hoist more sails from the deck.

Sailing along the Redwood Coast was tricky. The lumber industry grew fast in the 1860s, so there was a need for small, easy-to-handle two-masted schooners. These ships could get into the tiny, difficult ports that served the sawmills. Many places along this coast used chutes and wire systems to load lumber onto the small ships. Most of these ports were so small that they were called "dog-hole ports"—because they were supposedly just big enough for a dog to get in and out!

Dozens of these tiny ports were built. Almost any small cove or river mouth could become a loading spot. Each dog-hole was different, which is why ship captains often sailed to the same ports again and again. Sailors sometimes had to load their ships right among the rocks and cliffs in dangerous ocean waves.

The schooner design was perfect for the lumber trade. Its front-to-back sails allowed it to sail closer to the wind, enter small ports more easily, and needed fewer sailors than ships with square sails. These ships also needed to return to the lumber ports without having to load heavy ballast (weight) for stability. Some smaller schooners even had centerboards that could be pulled up. This helped the flat-bottomed ships get into very shallow water.

Lumber Cargo and Trade Routes

By 1882, the design of West Coast lumber ships was very different from ships built in New England. Lumber is a bulky cargo that doesn't need to be protected from the weather, and it's hard to store below deck. So, lumber ships were built without extra decks inside. Almost half of their cargo was carried on the main deck, not below it.

A "triangle trade" also developed. Ships would take lumber to Australia, then coal to Hawaii, and finally sugar back to San Francisco. The return cargoes (coal and sugar) were compact and heavy, so the ships didn't need the deep hulls of other vessels.

Interestingly, old bricks were sometimes used as ballast. In Fort Bragg, California, an old oven was found to be built with bricks from California factories like Richmond and Stockton. These bricks had traveled north from San Francisco as ballast on lumber ships. After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Fort Bragg sent tons of timber to San Francisco to help rebuild the city. On their way back, the ships used bricks from the Bay Area for weight and for new buildings in Fort Bragg.

Eventually, steam-powered ships became more reliable than sailing ships. Also, railroads started reaching more coastal areas. Sailing ships continued to compete with steamships and trains for a while, but the last sailing lumber schooner built for this purpose was launched in 1905.

Steam-Powered Lumber Schooners

Soon, steam schooners, which were wooden but had engines, took over from the small two-masted sailing ships in the dog-hole trade. Larger schooners, like the still-existing C.A. Thayer and the Wawona, were built for longer trips and bigger loads. West Coast shipyards kept building sailing lumber schooners until 1905 and wooden steam schooners until 1923.

Growing Bigger and Stronger

In 1907, people noticed that schooners were getting much bigger. The first three-masted schooner built on the Coast was launched in 1875. It was also the first lumber schooner to weigh more than 300 tons. Shipbuilders created the first four-masted schooner in 1886 and the first five-masted one in 1896. These larger ships were often used for overseas trade. Sailing schooners grew from 50 tons to 1,100 tons during this time. More than 50 major shipbuilders worked on the Pacific Coast during the era of these coastal schooners.

The need for coastal lumber shipping continued even after World War I. Trains didn't carry more lumber than ships until about 1905. Even in the 1870s, mills shipped lumber directly from some dog-hole ports to places like Asia and South America.

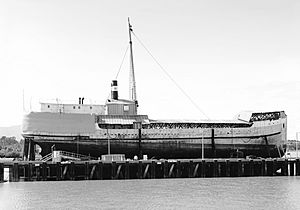

The Esther Johnson: A Special Ship

The last wooden steam lumber schooner ever built was the Esther Johnson. It was constructed in 1923 by Matthews Shipbuilding in Hoquiam, Washington. The Esther Johnson was a large wooden ship, weighing 1,104 gross tons. It was 208 feet 4 inches long, 43 feet 6 inches wide, and had a draft of 15 feet 2 inches. Its planks were made of three-inch thick Douglas fir.

During World War II, on March 29, 1943, the U.S. government bought the ship. By June, it had arrived in Australia to join the U.S. Army's fleet in the Southwest Pacific. The Esther Johnson arrived in Milne Bay on October 4, 1943. It was able to carry 100-foot wooden piles, enough to build an entire pier! This made it very important for building piers at military bases in Lae and Finschhafen in New Guinea, and Tacloban in the Philippines. The ship was bombed when it arrived at Lae, and both bombed and shot at (strafed) in Tacloban. By the end of the war, it was badly damaged by shipworms (tiny creatures that eat wood).

The leaking ship returned from Manila to Melbourne for repairs. Then, it went back to the Philippines and was put into a reserve fleet on December 20, 1947, at Subic Bay. Finally, it was sold to the Philippine government on February 23, 1948. Another older, slightly larger ship called the Barbara C (originally named Pacific) also served in the Southwest Pacific in the same important role.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |