Westonzoyland Pumping Station Museum facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Westonzoyland Pumping Station Museum of Steam Power & Land Drainage |

|

|---|---|

Westonzoyland Pumping Station Museum

|

|

| General information | |

| Town or city | Westonzoyland |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°05′27″N 2°56′40″W / 51.090928°N 2.944328°W |

|

Listed Building – Grade II*

|

|

| Official name | Westonzoyland Engine Trust Old Pumping Station at NGR ST3396232827 |

| Designated | 24 June 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1174295 |

| Completed | 1861 |

The Westonzoyland Pumping Station Museum is a cool place in Westonzoyland, Somerset, England. It's a museum all about amazing steam-powered machines and how they helped drain land. This special building is listed as Grade II*, meaning it's very important historically.

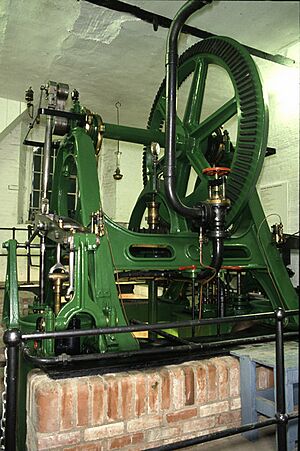

The museum is inside an old brick building from 1830. This was the first of many pumping stations built on the Somerset Levels. These low-lying lands often flooded. The main star of the museum is the 1861 Easton and Amos steam engine and pump. It's the only one of its kind still in its original spot and still working! The museum is run by a charity. They work hard to fix up and show off many other old steam engines and pumps. A special portable boiler makes the steam needed for the machines that move. You can also ride the Westonzoyland Light Railway. This short, 2 ft (610 mm) narrow-gauge railway runs along the site. It helps carry wood for the boiler.

Contents

How the Somerset Levels Were Drained

The Somerset Levels are flat, low areas of land. They were once underwater and then reclaimed. There's a clay belt near the coast and a lower peat belt further inland. People have tried to control water levels here for a very long time. Records from the 13th century show early efforts. The Domesday Book in 1086 mentioned drainage work on higher ground.

In the Middle Ages, big monasteries like Glastonbury Abbey, Athelney, and Muchelney Abbey did a lot of the drainage work. Around 1129, people worked to stop flooding on the River Parrett. By 1240, over 970 acres (about 3.9 square kilometers) near Westonzoyland had been reclaimed. Walls were built to hold back the Parrett River. These included Southlake Wall and Burrow Wall. The River Tone was even moved into a new channel.

Early Drainage Challenges

By 1500, about 70,000 acres (283 square kilometers) of land could flood. Only 20,000 acres (81 square kilometers) had been reclaimed. More land was reclaimed near the Parrett estuary in the late 1500s. In the early 1600s, there were plans to drain a large area called Sedgemoor. Local lords liked the idea, but commoners didn't. They would lose their grazing land.

King Charles I sold his part of the plan to a group that included Cornelius Vermuyden. He was a Dutch engineer. But the work was stopped by the English Civil War. Later, local people fought against it in Parliament. By 1638, much land was still undrained. Between 1785 and 1791, more of the peat moors were enclosed. In 1795, John Billingsley suggested digging "rhynes" (drainage channels). He wrote that thousands of acres had been enclosed in the past 20 years.

Steam engines that used coal were too expensive for pumping water back then. Windmills were not used much either, unlike in other flat areas like the Fens. Only two windmills were recorded on the Levels.

The First Pumping Station

The first machine-powered pumping station on the Somerset Levels was built in 1830. It helped drain the areas around Westonzoyland, Middlezoy, and Othery. This drainage system worked well. Soon, more drainage groups were formed, and more pumping stations were built.

The Westonzoyland pump first used a beam engine and a scoop wheel. This was like a water wheel running backward. But after 25 years, there were problems. The land had sunk as it dried out. Even though the wheel was raised, a better way was needed. So, in 1861, the Easton and Amos pump was put in. This pump lifts water from the local drainage channels, called rhynes, into the River Parrett.

The pump worked until 1951. By then, the local drainage system was connected to the King's Sedgemoor Drain. This drain released water further down the River Parrett. The water levels dropped, and the old pump couldn't pull water from the rhyne anymore. Also, the River Parrett's bank near the station was raised by about 8 feet (2.4 meters). The opening from the pump to the river is now bricked up. In 1951, a diesel pump was installed in a nearby building. It could pump 50 tons of water per minute. This meant the old steam pump was no longer needed.

The Pumping Station Building

The station building is made of brick with a special roof. It has a tall chimney that reaches 71 feet (21.6 meters) high. A small house was added next to it in the 1860s. This was for the person who looked after the station. The building was first listed as Grade II. But it was later upgraded to Grade II* because it's the only station left with a working engine.

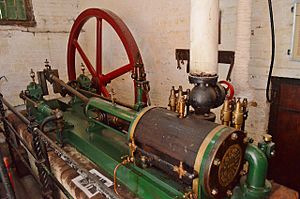

Next to the house is a long building with a 1914 Lancashire boiler. This boiler made the steam. There's also a forge where the station keeper made his own tools. The boiler needed to run all the time, so it used a lot of coal.

Bringing the Station Back to Life

In 1976, people from the Somerset Industrial Archaeology Society started to fix up the site. The Westonzoyland Engine Trust became a charity in 1980. In 1990, they bought the site. The engine house has been made strong again, and the pump house and chimney were rebuilt. A new exhibition hall was also built.

Until 2010, visitors couldn't go into the station keeper's house. Now, two rooms on the ground floor are open. The living room looks like it did in the 1930s or 1940s. The old kitchen area has displays of smaller items from the museum's collection. The upstairs rooms are still closed.

What You Can See at the Museum

At one end of the site is the pump house. This is where you'll find the 1861 Easton and Amos engine. It was built in London and designed by Charles Amos. It's a special engine that drives a pump invented by John Appold. A similar engine was shown at The Great Exhibition in 1851. It could lift 100 tons of water per minute! The engine first used Cornish boilers. These were replaced in 1914 with a Lancashire boiler. This boiler is too old to be fixed up now.

Besides the main pump, the museum has many other steam and diesel engines. These machines are connected to the area or to pumping water. They have engines from the early 1800s, the Victorian era, and the 1900s. You can find them in different buildings like the exhibition hall and the pump room. Most of the machines work, but some are still being fixed.

Steam for the working exhibits comes from an old Marshall portable boiler. It's like a portable engine but without the actual engine part. It was built in 1938 and used by Thames Water. It was later given to the London Museum of Water & Steam, then to Westonzoyland. It was fixed up with help from a special foundation. This boiler makes steam at 50 pounds per square inch (psi) for the other machines. It even has two whistles from old coal mines in Wales! In the outdoor area, you can also see a waterwheel pump unit and other pumps.

The museum displays engines from many different makers. These include 'quick revolution' engines by Belliss and Morcom. There are also horizontal engines by W. and F. Wills and J. Culverwell. The Culverwell engine was used in a brewery. The Wills engine worked in a brickworks.

Other cool things to see include two small de Laval steam turbines. There's also a small 'Wessex' steam turbine that washed milk bottles. A winch used to move railway wagons was built by J. Lynn. You can also see a Crossley diesel engine from 1935. The collection even has the boiler that powered the Telescopic Bridge, Bridgwater.

The Westonzoyland Light Railway is a short, 2 ft (610 mm) narrow-gauge railway next to the pumping station. It was built after the station closed to help move heavy machines around. Now, it carries timber from the wood pile to the boiler. The railway uses a Simplex diesel locomotive from 1968. It also has a Lister rail-truck from 1949. A steam winch is used to show how trucks were moved up a slope in old goods yards.

See also

- Association for Industrial Archaeology

- Industrial archaeology

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |