White swamphen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids White swamphen |

|

|---|---|

|

|

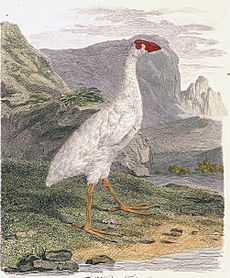

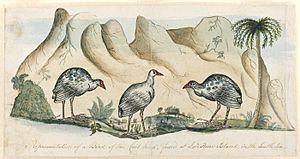

| Illustration (probably based on a live specimen) by Peter Mazell, from Arthur Phillip's 1789 book | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Porphyrio |

| Species: |

†P. albus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Porphyrio albus (White, 1790)

|

|

|

|

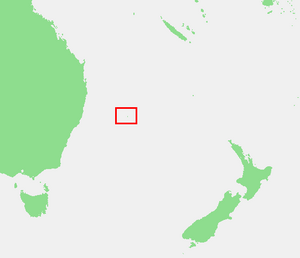

| Location of Lord Howe Island | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

Fulica alba White, 1790

Gallinula alba Latham, 1790 Porphyrio stanleyi Rowley, 1875 Porphyrio raperi Matthews, 1928 Kentrophorina alba Matthews, 1928 Notornis alba Pelzeln, 1860 Porphyrio albus albus Hindwood, 1940 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The white swamphen (Porphyrio albus) was a type of bird called a rail. It is now extinct. This bird lived only on Lord Howe Island, which is a small island east of Australia. People also called it the Lord Howe swamphen or white gallinule.

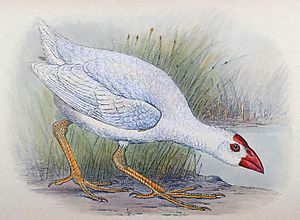

Sailors from British ships first saw these birds between 1788 and 1790. All the drawings and descriptions we have are from this time. Today, only two white swamphen specimens still exist. One is in the Natural History Museum of Vienna. The other is in Liverpool's World Museum. For a long time, people were confused about where these birds came from. They also argued about how to classify them. But now, scientists believe it was a unique species found only on Lord Howe Island. It was most similar to the Australasian swamphen.

The white swamphen was about 36 to 55 cm (14 to 22 in) long. The two known bird skins are mostly white. However, the Liverpool specimen also has some blue feathers. This is unusual for other swamphens. But old records say there were white, blue, and mixed blue-and-white birds. Baby white swamphens were black. They turned blue, then white as they grew older. This color change might have been a type of "progressive greying." This is when feathers lose their color as a bird gets older. The bird's beak, the fleshy part on its head (called a frontal shield), and its legs were red. It also had a small claw or spur on its wing.

Not much was written about how the white swamphen behaved. It might have been able to fly, but probably not very well. Because it was so calm and easy to catch, humans hunted it easily with sticks. People said it was once very common. But it might have been hunted to extinction before 1834. That is when people started living on Lord Howe Island.

Contents

Discovery and Classification

Lord Howe Island is a small island about 600 km (370 mi) east of Australia. Ships first arrived there in 1788. These included ships supplying a British penal colony and ships from the First Fleet. When the ship HMS Supply passed the island, its commander named it after Richard Howe.

Sailors from these ships caught native birds, including white swamphens. All the early descriptions and drawings of the bird were made between 1788 and 1790. The first mention of the bird was in a letter from David Blackburn in 1788. Other people who wrote about or drew the bird included Arthur Bowes Smyth, Arthur Phillip, and George Raper. There are at least ten drawings from that time. These old records show that the birds had white, blue, or mixed blue-and-white feathers.

In 1790, the surgeon John White officially described the white swamphen. He named it Fulica alba. The name alba comes from the Latin word for white. White thought the bird was most like the western swamphen. He described a bird skin from a museum. This skin is now the main example, or holotype, of the species. It is kept in the Natural History Museum of Vienna.

Another white swamphen specimen is in Liverpool's World Museum. This bird skin was once owned by Joseph Banks. Later, it was bought by Lord Stanley. His son gave it to the museum in 1850. For a while, people thought this second specimen came from New Zealand. This caused some confusion about the bird's classification.

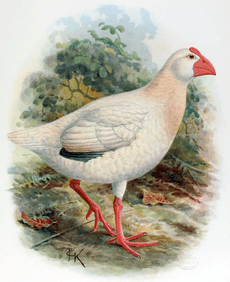

Many scientists thought the white swamphen was just an albino (all-white) version of the Australasian swamphen. In 1860, August von Pelzeln even put it in a different group, Notornis. He thought it was like the takahē from New Zealand. Other scientists, like Osbert Salvin and John Gerrard Keulemans, also drew it looking like a takahē.

In 1875, George Dawson Rowley named the Liverpool specimen as a new species, P. stanleyi. He thought it was different from the Vienna specimen. But in 1910, Tom Iredale showed there was no proof the white swamphen lived anywhere but Lord Howe Island. He noted that early visitors to Norfolk Island never saw it. After studying the Vienna specimen in 1913, Iredale said the bird belonged with other swamphens in the group Porphyrio. He said it did not look like the takahē.

In 2015, scientists Juan C. Garcia-R. and Steve A. Trewick studied the DNA of swamphens. They found that the white swamphen was most closely related to the Philippine swamphen. They used DNA from the Vienna specimen. This suggests a complex history for the bird.

In 2016, Hein van Grouw and Julian P. Hume studied the old records again. They confirmed that the white swamphen was a unique species found only on Lord Howe Island. They also found that its color changed with age. They concluded it was more similar to the Australasian swamphen than the Philippine swamphen. They believe the white swamphen likely came from Australasian swamphens.

Physical Description

The white swamphen was similar in size to the Australasian swamphen. Its wings were shorter than those of any other swamphen. The Vienna specimen's wing is 218 mm (8.6 in) long. Its tail is 73.3 mm (2.89 in). The beak with its frontal shield is 79 mm (3.1 in). Its leg bone (tarsus) is 86 mm (3.4 in), and its middle toe is 77.7 mm (3.06 in) long.

The white swamphen had a short middle toe. This was different from most other swamphens. It also had the shortest tail. Both known specimens have a claw or spur on their wings. This spur is clearer on the Vienna specimen.

Even though the known bird skins are mostly white, some old drawings show blue birds. Others show a mix of white and blue feathers. The bird's legs were red or yellow. Its beak and frontal shield were red. Its eyes were red or brown. Old notes say that baby chicks were black. They turned bluish-grey, then white as they grew up.

The Vienna specimen is pure white. But the Liverpool specimen has yellowish areas on its neck and chest. It also has blackish-blue feathers on its head and neck. There are blue feathers on its chest and purplish-blue feathers on its shoulders and back. Some tail feathers are purplish-brown. This suggests the Liverpool specimen was a younger bird. The Vienna specimen had reached its final white stage.

Specimen Condition

The Vienna specimen is a study skin today. This means it is flattened, not mounted like a stuffed bird. It is in good condition. Its legs have faded to a pale orange-brown. But they were probably reddish when the bird was alive.

The Liverpool specimen is also in good condition. However, it has lost some feathers from its head and neck. Its beak is broken. The bone underneath was painted red to make it look whole. Its legs were also painted red, so we don't know their original color. It's possible that only white specimens were collected because unusual-colored birds are often more interesting to collectors.

Behavior and Life Cycle

The white swamphen lived in wooded, wet areas in lowlands. We don't know anything about how they lived in groups or how they reproduced. Their nests, eggs, and calls were never described. They probably did not migrate.

In 1788, David Blackburn wrote about what the bird ate:

... On the shore we caught several sorts of birds ... and a white fowl – something like a Guinea hen, with a very strong thick & sharp pointed bill of a red colour – stout legs and claws – I believe they are carnivorous they hold their food between the thumb or hind claw & the bottom of the foot & lift it to the mouth without stopping so much as a parrot.

Some old accounts said the bird could not fly. But scientists Hein van Grouw and Julian P. Hume found that both specimens showed signs of spending more time on the ground. Their wings were shorter, and their feet were stronger. They were likely in the process of losing the ability to fly. Even if they could still fly a little, they probably didn't fly much. This is similar to other island birds. The white swamphen had very short wings for its size.

Van Grouw and Hume explained that white feathers in birds are rarely caused by albinism. Instead, it's often due to leucism or "progressive greying." These conditions mean the feathers don't have cells that make color. Leucism is inherited, and the white color is there from a young age. Progressive greying makes normally colored young birds lose color as they get older. They become white when they molt their feathers.

Since old records say the white swamphen changed from black to bluish-grey, then to white, it likely had progressive greying. This condition doesn't affect red and yellow colors. That's why the white swamphen's beak and legs stayed red. The large number of white birds on Lord Howe Island might be because of a small original group of birds. This would have helped the progressive greying trait spread.

Extinction

Even though the white swamphen was common in the late 1700s, it disappeared quickly. It was likely gone by 1834, when people first settled on Lord Howe Island. Whalers and sealers used the island for supplies. They might have hunted the bird to extinction. Habitat loss probably didn't play a role at first. Animal predators like rats and cats arrived later.

Many old records talk about how easy it was to hunt the island's birds. Sailors could catch many to feed their ships. In 1789, John White described how the white swamphen was caught:

They [sailors] also found on it, in great plenty, a kind of fowl, resembling much of the Guinea fowl in shape and size, but widely different in colour; they being in general all white, with a red fleshy substance rising, like a cock’s comb, from the head, and not unlike a piece of sealing-wax. These not being birds of flight, nor in the least wild, the sailors availing themselves of their gentleness and inability to take wing from their pursuits, easily struck them down with sticks.

The fact that they could be killed with sticks shows they were poor fliers. This made them easy targets for humans. They had no natural enemies on the island, so they were tame and curious. A doctor named John Foulis surveyed the island's birds in the 1840s. He didn't mention the white swamphen, so it must have been extinct by then.

Eight types of birds have become extinct on Lord Howe Island because of human activity. These include the Lord Howe pigeon, the Lord Howe parakeet, and the Lord Howe starling. The loss of so many native birds is similar to what happened on other islands, like the Mascarene Islands.

See also

In Spanish: Calamón de Lord Howe para niños

In Spanish: Calamón de Lord Howe para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |