Billy the Kid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Billy the Kid

|

|

|---|---|

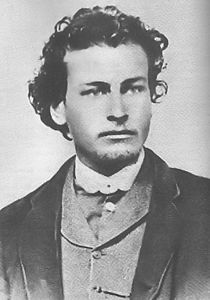

Photograph of Billy the Kid, c. 1880

|

|

| Born |

Henry McCarty

1859 |

| Died | 14 July 1881 (aged 21–22) Fort Sumner, New Mexico

|

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Old Fort Sumner Cemetery |

| Other names | William H. Bonney, Henry Antrim, Kid Antrim |

| Occupation |

|

| Height | 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) at age 17 |

Billy the Kid (born Henry McCarty; 1859 – 1881), also known as William H. Bonney, was a famous outlaw and gunfighter of the American Old West. He was known for his involvement in many conflicts and shootings. He also took part in New Mexico's Lincoln County War.

McCarty became an orphan at age 15. His first arrest was for stealing food when he was 16. He later escaped from jail and fled from New Mexico Territory to Arizona Territory. This made him a wanted person. In 1877, he started calling himself "William H. Bonney." After a conflict where a blacksmith died, McCarty became wanted in Arizona. He returned to New Mexico and joined a group of cattle rustlers. He became well known when he joined the Regulators and fought in the Lincoln County War of 1878.

His fame grew in December 1880 when newspapers wrote stories about him. Sheriff Pat Garrett captured McCarty later that month. In April 1881, McCarty was found guilty of a killing during the Lincoln County War. He was sentenced to hang. However, he escaped from jail on April 28, 1881, after two sheriff's deputies died. He stayed free for over two months. Garrett shot and killed McCarty, who was 21 years old, in Fort Sumner on July 14, 1881.

For many years after his death, stories spread that McCarty had survived. Several men even claimed to be him. Billy the Kid remains one of the most famous figures from the Old West. His life has been shown in more than 50 movies and several TV shows.

Who Was Billy the Kid?

Billy the Kid, whose real name was Henry McCarty, became a legend of the American Old West. He was known for his quick actions and his role in the wild frontier. His story is a mix of adventure, conflict, and a constant struggle with the law.

Early Life and Challenges

Henry McCarty was born in New York City. His parents, Catherine and Patrick McCarty, were from Ireland. He was likely born in 1859, possibly on September 17 or November 23. Records show he was baptized "Patrick Henry McCarthy" on September 28, 1859. He also had a younger brother, Joseph.

After his father died, Catherine and her sons moved to Indianapolis, Indiana. There, she met William Henry Harrison Antrim. The family then moved to Wichita, Kansas, in 1870. A few years later, Catherine married Antrim in Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory in 1873. Henry and Joseph were witnesses. Soon after, the family moved to Silver City, New Mexico. Joseph began using the name Joseph Antrim.

Sadly, Henry's mother, Catherine, died from tuberculosis in 1874. Before her death, William Antrim left the boys. This made Henry and Joseph orphans.

The Lincoln County War

A Conflict Begins

After returning to New Mexico, McCarty worked as a cowboy for an English rancher named John Henry Tunstall. Tunstall and his business partner, Alexander McSween, were rivals of powerful businessmen Lawrence Murphy, James Dolan, and John Riley. These three men had a lot of control over Lincoln County. They owned a beef contract with Fort Stanton and a popular store in Lincoln.

By February 1878, McSween owed money to Dolan. Dolan got a court order and asked Sheriff William J. Brady to take Tunstall's property. Tunstall put Bonney in charge of some horses to keep them safe. Meanwhile, Sheriff Brady gathered a large group of men to take Tunstall's cattle.

On February 18, 1878, Tunstall found out about the group on his land. He rode out to talk to them. During their meeting, a member of the group shot Tunstall. Another person then shot him in the back of the head, killing him. Tunstall's death started a big fight between the two groups. This fight became known as the Lincoln County War.

The Regulators Form

After Tunstall's death, McCarty and Dick Brewer made official statements against Sheriff Brady and his men. They got warrants to arrest them for murder. On February 20, 1878, while trying to arrest Brady, the sheriff's men arrested McCarty and two others. However, a U.S. Marshal named Robert Widenmann, who was McCarty's friend, helped free them.

McCarty then joined a group called the Lincoln County Regulators. On March 9, they captured Frank Baker and William Morton, who were accused of killing Tunstall. Baker and Morton were later killed while supposedly trying to escape.

On April 1, the Regulators surprised Sheriff Brady and his deputies. McCarty was shot in the leg during the fight. Sheriff Brady and Deputy Sheriff George W. Hindman were killed. A few days later, on April 4, 1878, Buckshot Roberts and Dick Brewer died in a shootout. Warrants were issued for many people involved, and McCarty was charged with the killings of Brady, Hindman, and Roberts.

The Battle of Lincoln

On July 14, McSween and about 50 or 60 Regulators went to Lincoln. They took positions in several buildings. McCarty and others were at the McSween house. Another group was on the roof of a saloon.

On July 16, the new sheriff, George Peppin, sent sharpshooters to attack the Regulators at the saloon. Peppin's men left when one of their snipers was killed. Peppin then asked for help from Colonel Nathan Dudley at Fort Stanton. Dudley refused at first but later arrived in Lincoln with soldiers. This helped the Murphy-Dolan side.

A big shooting battle started on July 19. McSween's supporters were inside his house. When the building was set on fire, the people inside started shooting. McCarty and the others ran out as the house burned. During the chaos, Alexander McSween was shot and killed. McCarty then shot and killed the person who shot McSween.

Life on the Run

After the Battle of Lincoln, McCarty and three others were near the Mescalero Indian Agency when a bookkeeper was killed. All four were accused, even though there was conflicting evidence. Only McCarty's accusation remained.

On October 5, 1878, U.S. Marshal John Sherman told Governor Lew Wallace that he had warrants for several men, including "William H. Antrim, alias Kid, alias Bonny." But he couldn't arrest them because the area was too dangerous. Governor Wallace offered a pardon on November 13, 1878, for anyone involved in the Lincoln County War. However, this pardon did not include people already accused of crimes, so McCarty was not covered.

On February 18, 1879, McCarty and his friend Tom O'Folliard saw an attorney named Huston Chapman killed. Eyewitnesses said McCarty and O'Folliard were innocent bystanders. McCarty wrote to Governor Wallace on March 13, 1879, offering to share information about the killing in exchange for a pardon. Wallace agreed to a secret meeting. McCarty met with Wallace on March 17, 1879. Wallace promised McCarty protection and a pardon if he testified to a grand jury.

McCarty agreed to testify and allowed himself to be arrested for safety. He gave his statement and testified in court. But the local district attorney refused to let him go. After several weeks, McCarty suspected Wallace would not grant him the pardon. McCarty escaped from the Lincoln County jail on June 17, 1879.

McCarty avoided trouble until January 10, 1880. He shot and killed Joe Grant at a saloon in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Reports said McCarty had been warned that Grant planned to kill him. McCarty reportedly disarmed Grant by asking to see his pistol, then made sure it wouldn't fire. When Grant tried to shoot him, McCarty drew his own gun and shot Grant.

In 1880, McCarty became friends with a rancher named Jim Greathouse, who introduced him to Dave Rudabaugh. On November 29, 1880, McCarty, Rudabaugh, and Billy Wilson were chased by a group led by a sheriff's deputy. They were cornered at Greathouse's ranch. McCarty said they were holding Greathouse hostage. The deputy offered to trade places with Greathouse, and McCarty agreed. The deputy later tried to escape and was shot and killed. The shootout ended in a standoff, and McCarty and his friends rode away.

A few weeks later, McCarty, Rudabaugh, Wilson, O'Folliard, Charlie Bowdre, and Tom Pickett rode into Fort Sumner. A group led by Pat Garrett was waiting for them. Garrett's group opened fire, killing O'Folliard. The others escaped.

Capture and Death

On December 13, 1880, Governor Wallace offered a $500 reward for McCarty's capture. Pat Garrett continued his search. On December 23, Garrett and his group captured McCarty, Pickett, Rudabaugh, and Wilson at Stinking Springs. The prisoners were taken to Fort Sumner, then to Las Vegas, New Mexico. Crowds of people came to see them.

The next day, an angry crowd gathered at the train station. They wanted Dave Rudabaugh, who had killed a deputy during an escape attempt. Garrett refused to give him up. McCarty later told a reporter he wasn't scared, saying, "if I only had my Winchester I'd lick the whole crowd."

After arriving in Santa Fe, McCarty wrote four letters to Governor Wallace, asking for a pardon. Wallace refused to help. McCarty went to trial in April 1881 in Mesilla, New Mexico. After two days, he was found guilty of Sheriff Brady's killing. He was sentenced to hang on May 13, 1881.

McCarty was moved to Lincoln and held in the town courthouse. On the evening of April 28, 1881, while Garrett was away, Deputy James Bell was alone with McCarty. McCarty asked to go outside to the outhouse. On their way back, McCarty slipped out of his handcuffs and hit Bell. McCarty grabbed Bell's revolver and shot him in the back as Bell tried to escape.

McCarty, still with leg shackles, broke into Garrett's office and took a loaded shotgun. He waited at the window for Deputy Bob Olinger to respond to the gunshot. When Olinger looked up, McCarty shot and killed him. After about an hour, McCarty freed himself from the leg irons with an axe. He got a horse and rode out of town. Some stories say he was singing as he left Lincoln.

The Final Encounter

While McCarty was on the run, Governor Wallace offered another $500 reward for him. Almost three months after his escape, Garrett went to Fort Sumner on July 14, 1881. He wanted to question Pete Maxwell, a friend of McCarty's. Around midnight, Garrett and Maxwell were in Maxwell's dark bedroom when McCarty unexpectedly walked in.

Stories differ about what happened next. The most common version says McCarty didn't recognize Garrett in the dark. He drew his revolver and asked in Spanish, "¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?" (meaning "Who is it? Who is it?"). Recognizing McCarty's voice, Garrett drew his revolver and fired twice. The first shot hit McCarty in the chest, just above his heart. The second shot missed.

A few hours later, a local judge gathered a group of six people to examine the scene. They interviewed Maxwell and Garrett and looked at McCarty's body. They confirmed it was McCarty. He was buried the next day.

Five days after McCarty's death, Garrett went to Santa Fe to collect the $500 reward. The acting governor refused to pay. However, people in other New Mexico cities raised over $7,000 for Garrett. A year later, the New Mexico government officially granted Garrett the $500 reward.

Because some people claimed Garrett had unfairly ambushed McCarty, Garrett felt he needed to tell his side of the story. He asked his friend, journalist Marshall Upson, to help him write a book. The book, The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid, was published in 1882. It later became an important source for historians.

Rumors of Survival

Over time, stories grew that Billy the Kid had not been killed. Some believed Garrett had faked his death to help him escape the law. For 50 years, several men claimed to be Billy the Kid. Most of these claims were easily proven false. However, two claims have been discussed more.

In 1948, a man from Texas named Ollie P. Roberts, also known as Brushy Bill Roberts, claimed he was Billy the Kid. He asked the New Mexico Governor for a pardon, but his claims were dismissed. Roberts died soon after. Still, his hometown of Hico, Texas, opened a Billy the Kid museum.

Another man, John Miller from Arizona, also claimed to be McCarty. His family supported this claim after his death in 1938. In 2005, Miller's remains were examined to compare his DNA with blood samples from the old Lincoln County courthouse. However, the results were not helpful.

In 2004, researchers wanted to examine the remains of Catherine Antrim, McCarty's mother. Her DNA could be compared with the body buried in William Bonney's grave. As of 2012, her body had not been examined.

In 2015, a historian asked the state of New Mexico to officially issue a death certificate for McCarty. The request aimed to settle the debate about his death.

Photographs

As of 2021[update], only one photo is officially confirmed to show Billy the Kid. Other photos that might show him are still debated.

The Dedrick Ferrotype

One of the few things left from McCarty's life is a small 2-by-3-inch (5.1-by-7.6-centimeter) ferrotype photograph. It was taken by an unknown photographer around 1879 or 1880. The picture shows McCarty wearing a vest, a sweater, a slouch hat, and a bandana. He is holding an 1873 Winchester rifle. For many years, this was the only photo that experts agreed showed McCarty. It survived because McCarty's friend, Dan Dedrick, kept it. In 2011, the original photo was sold at an auction for $2.3 million.

The photo shows McCarty wearing his revolver on his left side. This made people think he was left-handed. However, ferrotype photos create a reversed image. So, he was actually right-handed and wore his pistol on his right hip. Some historians believe he could use both hands equally well.

The Croquet Tintype

In 2010, a 4-by-6-inch (100 mm × 150 mm) ferrotype was bought at a shop in Fresno, California. Some claim it shows McCarty and members of the Regulators playing croquet. If true, it would be the only known photo of Billy the Kid and the Regulators together, including their wives and female friends. However, some experts believe the photo does not show McCarty. Others, using facial recognition software, believe it does.

In 2015, officials at Lincoln State Monument said they could not confirm the photo showed McCarty or others from that time. The small size of the figures and the background landscape made it hard to be sure. However, in October 2015, an authentication company stated the image was real after several experts examined it.

Posthumous Pardon Request

In 2010, New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson turned down a request to pardon McCarty after his death. The pardon was considered to fulfill a promise Governor Lew Wallace supposedly made in 1879. Richardson's decision, citing "historical ambiguity," was announced on his last day in office.

Grave Markers

In 1931, Charles W. Foor, a tour guide at Fort Sumner Cemetery, raised money for a permanent marker for the graves of McCarty, O'Folliard, and Bowdre. A stone memorial with their names and death dates, under the word "Pals," was put up.

In 1940, a stone cutter named James N. Warner donated a new marker for Bonney's grave. It was stolen in 1981 but found days later in California. New Mexico Governor Bruce King arranged for it to be returned and reinstalled in May 1981. Both markers are behind an iron fence. However, in 2012, vandals entered the area and pushed over the stone.

Popular Culture

Billy the Kid's life and adventures have been shown in many forms of popular culture. These include comic books, literature, films, music, stage plays, radio shows, television series, and video games.

See also

- Folklore of the United States

- List of Old West gunfighters

- List of Old West lawmen

In Spanish: Billy the Kid para niños

In Spanish: Billy the Kid para niños