Willis Ward facts for kids

|

|

| Michigan Wolverines – No. 61 | |

|---|---|

| Position | End |

| Personal information | |

| Born: | December 28, 1912 Alabama |

| Died: | December 30, 1983 (aged 71) Michigan |

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) |

| Weight | 185 lb (84 kg) |

| Career history | |

| College | Michigan (1932–1934) |

| High school | Northwestern |

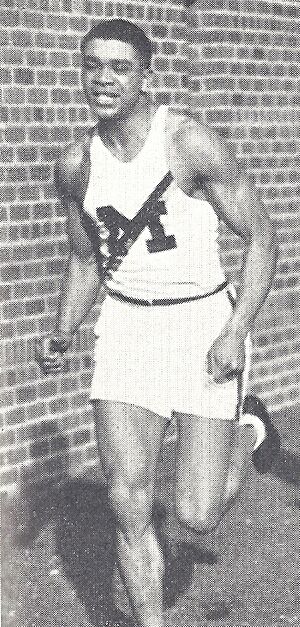

Willis Franklin Ward (December 28, 1912 – December 30, 1983) was an amazing athlete. He was a star in both track and field and American football. In 1981, he was honored by being added to the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor.

Willis Ward was named Michigan High School Athlete of the Year. He even set a national record in the high jump. At the University of Michigan, he was a college champion in the high jump, long jump, 100-yard dash, and 440-yard dash. In 1933, he almost won the Big Ten Athlete of the Year award. He was a three-time All-American in track and field. He also won eight Big Ten championships.

In football, Ward was only the second African-American player to earn a varsity letter for the Michigan Wolverines football team. He earned letters in 1932, 1933, and 1934. In 1934, a big problem happened. The Georgia Tech team refused to play if Ward was on the field. University officials decided to keep Ward out of the game. His teammate, Gerald R. Ford, who later became president, reportedly threatened to quit the team because of this decision. After being left out of the Georgia Tech game, Ward scored all 12 of Michigan's points that year in other games. No other Michigan player scored any points besides him in those games.

Later in life, Ward became a lawyer in Detroit. He also worked for Ford Motor Company. From 1966 to 1973, he was a member of the Michigan Public Service Commission. He even served as its chairman from 1969 to 1973. He also became a judge in Wayne County, Michigan.

Contents

- Willis Ward's Early Life

- Willis Ward at the University of Michigan

- A Star Freshman in Track

- First African-American Football Player in Decades

- Willis Ward's Amazing 1933 Track Season

- Willis Ward's 1933 Football Season

- Almost Big Ten Athlete of the Year

- Willis Ward's 1934 Track Season

- Willis Ward's 1934 Football Season

- The 1934 Georgia Tech Game Controversy

- How the Incident Affected Ward

- Willis Ward's Later Life

- Images for kids

Willis Ward's Early Life

Willis Ward was born in Alabama in 1913. His father, Henry R. Ward, moved to Detroit. He worked in a Ford Motor Company factory. Willis's mother, Bessie, was from Georgia.

Ward went to Detroit's Northwestern High School. He was excellent in both track and football there. As a junior, he was named Michigan High School Athlete of the Year. He set a national high school record in the high jump, jumping 6 feet, 4.5 inches. He also won city championships in hurdles.

Willis Ward at the University of Michigan

A Star Freshman in Track

Willis Ward attended the University of Michigan from 1931 to 1935. He became one of the best track athletes in the school's history. As a freshman in 1932, Ward was amazing at the high jump. He won the NCAA high jump championship in June 1932. His best jump that year was 6 feet, 7.5 inches. This was even higher than the jump that won the gold medal at the 1932 Summer Olympics. However, Ward did not make the Olympic team.

Ward was good at more than just the high jump. An Associated Press article in 1932 said he could run hurdles and broad jump. He could even throw the 16-pound shot. He was only 19 years old and had a great build for a track athlete. He was also quiet and well-liked by his coaches and teammates.

When Ward decided to try out for the football team as a sophomore, track fans worried. They thought he might get hurt. The Associated Press wrote that fans believed he would be the greatest track athlete ever for Michigan. But he loved football and wanted to play. Michigan's track coach, Chuck Hoyt, said Ward was "his own boss" and football was his "recreation."

First African-American Football Player in Decades

Ward's decision to play football also brought up questions about race. George Jewett was Michigan's first African-American football player in 1890. But for 40 years after Jewett, Michigan had not played another African-American player. Some people believed this was due to racism from the coach at the time, Fielding H. Yost.

Ward had planned to go to Dartmouth College. But Michigan's head coach, Harry Kipke, promised him a fair chance to play football. So, Ward enrolled at Michigan. Coach Kipke had played with African-American athletes before. He really wanted Ward on his team. A book about African-American athletes at Michigan says Kipke even threatened to fight people who didn't want Ward to play.

Ward proved himself in spring football practice in May 1932. Coach Kipke told his players to hit Ward hard during practice. He said if Ward didn't quit, he knew he had a great player. The United Press reported that Ward, along with Jerry Ford, showed great skill. Ward, described as a "giant negro," was seen as the best new athlete.

Ward made the team in 1932. He started four games as an end. The team captain, Ivy Williamson, welcomed Ward. He told Ward to let him know if he had any problems. The Associated Press noted that Ward would rather earn an "M" in football than be an Olympic champion.

The 1932 Michigan Wolverines football team had a perfect season, winning all 8 games. They outscored their opponents 123 to 13. They also won the national championship.

Willis Ward's Amazing 1933 Track Season

In the 1933 track season, Ward was so good that people called him Michigan's "one-man track team." He became famous across the country. He helped Michigan win Big Ten championships in both indoor and outdoor track. Coach Hoyt called Ward "a good 'un." He also praised Ward for being humble and handling the attention well.

Michigan won the Big Ten track meet with 60.5 points. Ward scored 18 of those points by himself. One writer said Michigan would have finished second without the "huge, versatile negro." At the meet, Ward won the 100-yard dash and the high jump. He also placed second in the 120-yard high hurdles and the broad jump. His performance was called the "greatest individual performance" since 1918.

Even TIME magazine wrote about Ward's amazing performance. Time noted that Ward helped Michigan win the Western Conference title. He won the 100-yard dash in 9.6 seconds. He won the high jump and placed second in the broad jump. He also pushed Ohio State's Jack Keller to a world record time in the high hurdles. The 18 points he scored helped Michigan win. Time also mentioned that Ward was a quiet, humble, and good student. He was the first African-American elected to Sphinx, Michigan's junior honor society.

At the Drake Relay Carnival in April 1933, he finished second in the 100-yard dash. He lost closely to Ralph Metcalfe. The 1934 Michigan yearbook, the Michiganensian, said Ward almost single-handedly won the Butler Relays. He scored 13 of the team's 18.75 points. He also tied a world record in the 60-yard dash. At the Big Ten indoor track championship, Ward was easily the best star. He won the 60-yard dash, the 70-yard high hurdles, and the high jump.

Willis Ward's 1933 Football Season

In 1933, Ward started all eight games for Michigan as a right end. He was a very important player in Michigan's second straight undefeated football season. They won another national championship. Time magazine gave credit to Ward and halfback Herman Everhardus. Ward blocked a kick that saved Michigan from losing points against Illinois. Coach Kipke also praised Ward for his excellent play. Michigan's left end, Ted Petoskey, was named a first-team All-American. Ward also received honorable mention All-American honors.

Almost Big Ten Athlete of the Year

In December 1933, Ward came in second for the Associated Press Big Ten Athlete of the Year award. Duane Purvis of Purdue won by only two votes. The AP described Ward as "Michigan's 'one-man track team.'" They pointed out his great contributions in both football and track. Ward could run the 100-yard dash in 9.6 seconds. He high jumped 6 feet, 7.5 inches. He broad jumped 24 feet and was also great at high hurdles.

Willis Ward's 1934 Track Season

In 1934, Ward won the Big Ten long jump championship. He jumped 23 feet, 2.25 inches.

Willis Ward's 1934 Football Season

The 1934 football season was tough for Michigan. The team had a record of 1 win and 7 losses. It was also remembered for the unfair event that kept Ward out of the game against Georgia Tech. Even though he was excluded from that game, Willis started every other game. He played five games at right end and two games at halfback.

Michigan scored only 21 points in the entire 1934 season. Ward scored 12 of those points. In fact, Michigan scored nine points against Georgia Tech. Ward's 12 points were the only points scored by Michigan in the seven games he played. Michigan was shut out in the first two games. Then they beat Georgia Tech. The next week, Michigan lost to Illinois 7-6. Ward scored Michigan's only touchdown from the line of scrimmage that season. His touchdown came on a trick play. The Chicago Tribune said Ward's speed helped him get past the Illinois defense. After being shut out in three more games, Michigan lost to Northwestern 13-6. Ward scored Michigan's only points with two field goals. So, all 12 of Michigan's points in games outside of the Georgia Tech game were scored by Ward.

The 1934 Georgia Tech Game Controversy

Despite all his achievements, Willis Ward is most remembered for the game he was not allowed to play. In 1934, Michigan was scheduled to play Georgia Tech. When Georgia Tech's coach, W. A. "Bill" Alexander, found out Michigan had an African-American player, he refused to let his team play if Ward was on the field. Coach Alexander had written to Michigan's athletic director, Yost, in 1933 about Ward.

As the game got closer, news spread that Georgia Tech insisted Ward not play. There were rumors that Michigan officials might agree to this demand. Ward's right to play became a huge debate on campus. Students and teachers held large meetings and protests. Some demanded that Ward must play or the game should be canceled. Many groups, including the NAACP, protested to the university. The student newspaper, The Michigan Daily, said the athletic department was either "astonishingly forgetful" or "extraordinarily stupid" for scheduling the game.

Time magazine reported on the uproar. They said 1,500 Michigan students and teachers signed a petition. It asked that Willis Ward be allowed to play. Time also reported that 200 "campus radicals" threatened to stop the game. They planned to stand in the middle of the field. Rumors of a sit-down protest spread. One former student remembered bonfires and shouts of "Kill Georgia Tech" the night before the game. To stop any disruptions, Yost hired a Pinkerton agent. This agent was supposed to join student groups supporting Ward.

Athletic officials argued that Ward should not play. They said it would be rude to Georgia Tech. They also feared Ward might get hurt by unfair hits. Playwright Arthur Miller, who was a student writer then, learned how strongly the Georgia Tech team felt. He heard from friends that Georgia Tech players said they would hurt Ward if he played. Miller was very angry and wrote an article for The Michigan Daily, but it was not published.

In the end, Ward was not allowed to play. But Georgia Tech agreed to keep their own star player, Hoot Gibson, out of the game in return. There are different stories about where Ward was during the game. Time magazine said Ward "sat calmly in a radio booth" and watched Michigan win 9-2. Another account says Ward was not even allowed to watch from the press box or the bench. He spent the afternoon in a fraternity house. A third story says Coach Kipke sent Ward to scout another Michigan game in Wisconsin. The day after the game, The Michigan Daily said everyone involved in the "Ward affair" lost respect. In Georgia, some sports writers blamed the player exchange for Georgia Tech's loss. They said "Willis Ward won the football game" because losing Gibson hurt Georgia Tech more than losing Ward hurt Michigan.

How the Incident Affected Ward

Willis Ward was one of the most successful athletes in Michigan's history. He earned six varsity letters in football and track. In track, he won Big Ten titles in the 100-yard dash (1933), high jump (1933 and 1935), 400-meter dash (1933), and long jump (1934). He even beat Jesse Owens in the 100-yard dash several times. Because of his many skills, Ward was considered a strong candidate for the U.S. decathlon team in the 1936 Olympics.

However, the Georgia Tech incident made Ward angry and disappointed. He said it took away his desire to compete. Ward thought about quitting football. He even wrote a letter to Coach Kipke about leaving the team. He later said that not being allowed to play against Georgia Tech destroyed his will to compete. "It was the fact that I couldn't play in the Georgia Tech game," he recalled. "That all of a sudden, the practice that you just did because it was the thing to do that was good—a tremendous amount of burnt up energy—all of a sudden becomes drudgery."

His one sports highlight in 1935 was beating Jesse Owens in the 60-yard dash and 65 high hurdles at Yost Fieldhouse. Ward's times were very close to Owens' until the NCAA track and field championship. He took part in the Olympic trials in 1936. But he had lost his competitive drive. Ward said he did not train his best and failed to make the U.S. team. "They were urging me to go out in '36," Ward remembered. "But that Georgia Tech game killed me. I frankly felt they would not let black athletes compete." In 1976, Ward said about the incident: "It was like any bad experience—you can't forget it, but you don't talk about it. It hurts."

Willis Ward's Later Life

Willis Ward went on to earn a law degree from Detroit College of Law in 1939. He had a great career as a lawyer and judge. In 1966, Michigan Governor George Romney appointed Willis to the Michigan Public Service Commission. This state agency regulates public services in Michigan. Willis became chairman of the PSC in 1969 and served until 1973. Ward was later elected a probate judge in Wayne County, Michigan.

Ward was inducted into the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor in 1981. He was part of the fourth group of people to receive this honor.

Images for kids