Winnebago War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Winnebago War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||||

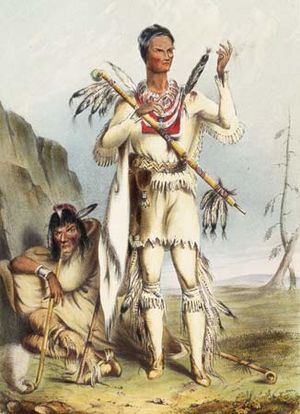

Red Bird, dressed in white buckskin for his surrender to U.S. authorities, with Wekau |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Prairie La Crosse Ho-Chunks, with a few allies | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Red Bird | Henry Atkinson, Henry Dodge |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 7 killed | 9–11 civilians killed | ||||||||

The Winnebago War, also known as the Winnebago Uprising, was a short conflict in 1827. It happened in the Upper Mississippi River area, mostly in what is now Wisconsin. It wasn't a full-scale war, but a series of attacks on American settlers. These attacks were carried out by some members of the Winnebago (or Ho-Chunk) Native American tribe.

The Ho-Chunks were upset because many lead miners were moving onto their lands without permission. They also heard false rumors that the United States had handed over two Ho-Chunk prisoners to a rival tribe. Most other Native American tribes in the region chose not to join the uprising. The conflict ended when U.S. officials showed their military strength. Ho-Chunk chiefs gave up eight men who had been involved in the violence, including Red Bird. American officials thought Red Bird was the main leader. Red Bird died in prison in 1828 while waiting for his trial. Two other men were later pardoned by President John Quincy Adams and set free.

After the war, the Ho-Chunk tribe had to give up the lead mining region to the United States. The Americans also increased their military presence in the area. They built Fort Winnebago and reopened two other forts. This conflict made some officials believe that Americans and Native Americans could not live peacefully together. They thought Native Americans should be moved westward. This idea became known as Indian removal. The Winnebago War happened before the larger Black Hawk War of 1832. Many of the same people were involved, and the issues were similar.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

After the War of 1812, the United States wanted to stop wars among Native Americans. This was not just for peace. It was also to make it easier for the U.S. to get Native American land. By the late 1820s, the main goal was to move tribes to the West. This policy was called Indian removal. In 1825, U.S. officials signed a treaty at Prairie du Chien. This treaty set the boundaries for the tribes in the region.

However, many Americans began to enter Ho-Chunk lands. They were looking for lead to mine along the Fever (later Galena) River. Native Americans had mined this area for thousands of years. Selling lead was an important part of the Ho-Chunk economy. Ho-Chunks tried to make the miners leave, but they often faced abuse. Some U.S. officials wanted the mining region for Americans. They tried to stop the Ho-Chunks from mining.

False Rumors and Growing Tensions

In October 1826, Colonel Snelling moved soldiers from Fort Crawford to Fort Snelling. He hoped to reduce fighting between the Dakotas (Sioux) and the Ojibwes (Chippewas). The two Ho-Chunk prisoners were also moved to Fort Snelling. In May 1827, Dakotas attacked an Ojibwe group near Fort Snelling. Colonel Snelling arrested four Dakotas and gave them to the Ojibwes, who killed them. This made some Dakotas angry. They told the Ho-Chunks to help them fight the Americans. They falsely said that the Ho-Chunk prisoners had also been given to the Ojibwes to be killed.

The false story about the prisoners, along with the constant trespassing by American miners, made some Ho-Chunks decide to fight. The Ho-Chunks thought the Americans were weak because Fort Crawford was empty. They stopped talking with the United States and got ready for war.

The Attacks Begin

In late June 1827, a Ho-Chunk leader named Red Bird went to Prairie du Chien. He was with Wekau and Chickhonsic. They wanted revenge for what they believed were the deaths of the Ho-Chunk prisoners. They couldn't find the person they were looking for. Instead, they went to the cabin of Registre Gagnier. Gagnier welcomed the three Ho-Chunks into his home for a meal.

What happened next is told differently in various stories. One account says Red Bird shot and killed Gagnier. Chickhonsic shot and killed Solomon Lipcap, a worker or friend. Wekau tried to shoot Gagnier's wife, but she fought him and escaped with her young son. Wekau only managed to hurt Gagnier's baby daughter, who survived. Another story says only Red Bird committed the killings. Red Bird and his friends returned to their village at Prairie La Crosse. A celebration was held there.

On June 30, 1827, the Prairie La Crosse Ho-Chunks attacked again. About 150 Ho-Chunks, with a few Dakota allies, attacked two American boats. This happened on the Mississippi River, near the Bad Axe River. Two Americans were killed and four were hurt. About seven Ho-Chunks died in the attack or later from their injuries. This attack was important because it was the first act of war by Native Americans in the region since the War of 1812.

The Prairie La Crosse Ho-Chunks tried to get other tribes to join them. They asked the Dakotas, Potawatomis, and other Ho-Chunk groups. Most tribal leaders felt sympathy for the Ho-Chunks but chose to stay neutral. Some Potawatomis killed American farm animals. However, Potawatomi leaders Billy Caldwell, Alexander Robinson, and Shaubena rode around telling their people to stay out of the war. They would do the same during the Black Hawk War five years later. Many Ho-Chunks also did not support Red Bird's actions. Without more allies, the plan for a widespread war failed. By mid-July, the "Red Bird Uprising" was mostly over.

What Happened Next

After the conflict, General Atkinson promised the U.S. government would look into the Ho-Chunks' complaints. These complaints were about the lead mining region. Thomas McKenney asked for military help to remove American miners who were on Ho-Chunk land without permission. However, after the war, many more settlers moved into the area. U.S. officials could not or would not stop them. By January 1828, there were as many as 10,000 illegal settlers on Ho-Chunk land. This included military general Henry Dodge, who started a mining camp after the war. He even boasted that the U.S. Army could not make him leave.

The Ho-Chunks had no other choice. On August 25, 1828, they signed a temporary treaty with the United States. They agreed to sell the land where the miners were. A more formal treaty would be held later.

Eight Ho-Chunks were held by the U.S. government at Fort Crawford for trial. American officials especially wanted to convict Red Bird. They believed he was the leader of the uprising. Historians say this belief was wrong. Americans did not understand how Ho-Chunk society was organized. Red Bird was well-known to white settlers. So, they blamed him, wrongly thinking he was a leader. Red Bird was never tried. He became sick and died in prison on February 16, 1828.

The trials were delayed because it was hard to gather witnesses, lawyers, and interpreters. The trials finally began in August 1828. Judge James Duane Doty was in charge. Wau-koo-kau and Man-ne-tah-peh-keh, two warriors held for earlier events, were released. This was because there were no witnesses. Three Ho-Chunks held for the boat attack were also released. Only two men, Wekau and Chickhonsic, were put on trial. During the trial, it became clear that Red Bird had committed the acts at the Gagnier cabin. There was not enough proof to convict Wekau and Chickhonsic. Even so, the jury found them responsible. Judge Doty sentenced them to death, as the law required. Their lawyer asked for a new trial, saying the jury ignored the evidence. So, Doty stopped the death sentences.

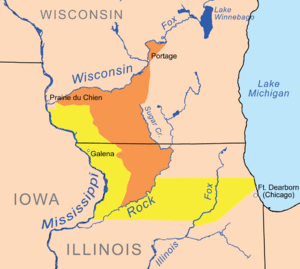

On November 3, 1828, President John Quincy Adams pardoned the prisoners. He was told that executing them would likely start another uprising. In exchange, the Ho-Chunks gave up more land. In July and August 1829, treaties were signed at Prairie du Chien. The Three Fires Confederacy and the Ho-Chunks officially gave the lead mining region to the United States. They received yearly payments of $16,000 and $18,000.

To prevent more uprisings, the United States decided to have a stronger military presence. Fort Crawford was reopened. Fort Dearborn in Chicago, which had been empty since 1823, was also reopened. A new outpost, Fort Winnebago, was built in October 1828. It was located where the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers met.

The conflict also changed U.S. policy toward Native Americans. Before, many Americans thought Native Americans should become like white Americans. But for some, the Winnebago War showed that Native Americans and Americans could not live peacefully together. In his State of the Union Address on December 2, 1828, President Adams said the "civilization" policy had failed. He said that Indian removal—moving tribes to the West—was the future policy. This policy would be continued by Adams's successor, Andrew Jackson.

Images for kids

-

Red Bird, dressed in white buckskin for his surrender to U.S. authorities, with Wekau

-

Land ceded to the U.S. at Prairie du Chien in 1829 by the Three Fires Confederacy (in yellow) and the Ho-Chunk tribe (in orange).

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |