Military Women's Memorial facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Military Women's Memorial |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Arlington County, Virginia, United States |

| Area | 4.2 acres (1.7 ha) |

| Established | October 17, 1997 |

| Visitors | 200,000 (in 2016) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | |

| Architect | Weiss/Manfredi |

| NRHP reference No. | 95000605 |

| Added to NRHP | November 13, 1982 |

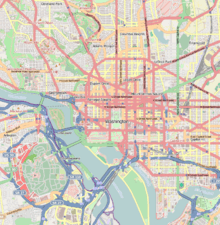

The Military Women's Memorial, also known as the Women In Military Service For America Memorial, is a special place that honors women who have served in the United States Armed Forces. It is located at the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia.

The building that holds the memorial was first called the Hemicycle. It was built in 1932 to be a grand entrance to the cemetery. However, it was never used for this purpose and became quite run down by 1986. In 1985, the U.S. Congress decided to create a memorial for women in the military. The Hemicycle was chosen as the perfect spot in 1988.

Architects Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi from New York City won a design contest for the memorial. Their first design caused some debate, so they worked on it for two more years. A new design was approved in 1992, and the final plan in 1995. Construction started in June 1995, and the memorial was officially opened on October 18, 1997.

The memorial is special because it blends old-style (Neoclassical) and modern architecture. It kept most of the original Hemicycle but added a beautiful skylight. This skylight not only honors servicewomen but also leads visitors to the memorial area below.

Contents

The Hemicycle Building

Why the Hemicycle Was Built

The Hemicycle is the grand entrance to Arlington National Cemetery. It was built to celebrate the 200th birthday of George Washington, America's first president and a hero of the American Revolutionary War. Many new projects were planned in Washington, D.C., to honor this special anniversary.

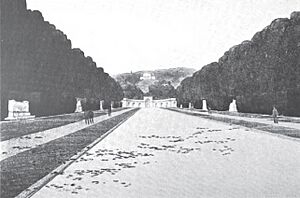

One of these projects was the Arlington Memorial Bridge, which crosses the Potomac River. To connect this bridge to Arlington National Cemetery, a wide road called Memorial Avenue was built. The Hemicycle was designed to be the new main entrance to the cemetery from this avenue.

In 1924, Congress set aside money to build Memorial Avenue and the Hemicycle. The architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White designed both the bridge and the new cemetery entrance. William Mitchell Kendall, an architect from the firm, created the Hemicycle's design. The design was approved in 1928.

Work on Memorial Avenue began in 1930, and construction on the Hemicycle started in July 1931. The Hemicycle was informally opened by President Herbert Hoover in January 1932. It cost about $900,000 to build.

Finishing the Hemicycle

The Hemicycle almost didn't get finished because of the Great Depression. Money for the project was cut in 1933. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed in spending federal money on public projects to help the economy and create jobs. He signed a law that provided $6 billion for public works. Washington, D.C., received some of this money to finish the Hemicycle and Memorial Avenue.

Work continued, and by September 1936, the Hemicycle was considered "finished." Its fountain was working, and lights were installed. Trees were also planted along Memorial Avenue.

What the Hemicycle Looks Like

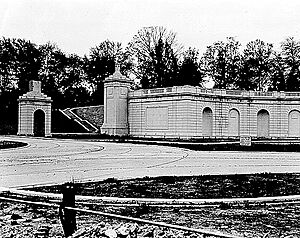

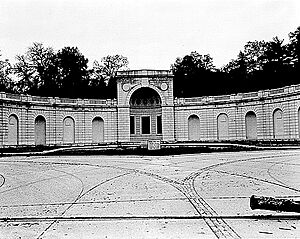

The Hemicycle is a large, curved building that is 30 feet (9 meters) high and 226 feet (69 meters) wide. It acts as a retaining wall for the hill behind it. In the middle, there's a curved space called an apse, which is 20 feet (6 meters) wide and 30 feet (9 meters) high.

The Hemicycle is made of strong concrete and covered with granite stone. The Great Seal of the United States is carved in granite above the apse. On either side are the seals of the United States Department of the Army and the United States Department of the Navy. Along the front of the Hemicycle are 10 false doors or niches. These were meant to hold sculptures or artworks, but they were never filled.

On top of the Hemicycle is a wide terrace. Originally, you could only reach this terrace by going through gates at either end and climbing stairs. However, these entrances were locked for over 50 years.

Memorial Avenue splits into two roads at the Hemicycle, leading through iron gates into Arlington National Cemetery. The north gate is called the Schley Gate, and the south gate is the Roosevelt Gate. Each gate has gold wreaths and shields representing the military branches that existed in 1932.

Tall granite pillars stand at each end of the Hemicycle and next to the gates. These pillars are topped with decorative urns and gold-lit lamps.

How the Hemicycle Changed Over Time

The Hemicycle was never fully completed as planned. A large statue was supposed to be placed in the central apse, but it never was. Also, the niches were never filled with memorials. Because there was no parking nearby, and it was hard to reach, few people visited the site.

By the 1980s, the Hemicycle was in bad shape. It had never been used for ceremonies, and neither the cemetery nor the National Park Service maintained it well. Many stone blocks were damaged, plants were overgrown, and moss covered the carvings. Weeds grew everywhere, and the sidewalks were cracked. The building also leaked, staining many of the stones.

Creating the Women In Military Service For America Memorial

Getting Approval for the Memorial

In the early 1980s, women who had served in the military started asking for a memorial to honor them. They gained support from groups like the American Veterans Committee. Representative Mary Rose Oakar introduced a bill in Congress to create the memorial.

At first, some government officials opposed the idea, saying that existing memorials already honored women. However, United States Air Force Brigadier General Wilma Vaught argued that a simple statue wasn't enough. She believed a memorial with exhibits about women's contributions was needed. In late 1985, a foundation was created to raise money and push for the memorial.

The foundation gained support from large veterans' groups and the United States Department of Defense. This helped overcome objections. Finally, on November 6, 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed the bill into law. This law gave the foundation five years to raise money and start building the memorial.

Choosing the Memorial's Location

After retiring in 1985, General Vaught became the main spokesperson for the memorial foundation. She believed the memorial should be near an existing military site. The search for a location began in 1988.

At first, they looked at the National Mall, but no spot was big enough. Then, General Vaught saw the Hemicycle. She learned it was unused and in disrepair. She realized it would be easier to get approval for the Hemicycle site than for a spot on the National Mall. Since the foundation had a five-year deadline, she wanted to move quickly.

The Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) had to approve the site. National Park Service officials said the memorial would help restore the Hemicycle. General Vaught promised to build an educational memorial with computers, exhibits, and a theater. The CFA liked the idea of restoring the landmark and thought the location was very fitting. They stressed that the design should not drastically change the Hemicycle's look.

On June 28, 1988, the CFA unanimously approved the Hemicycle as the site for the memorial.

The Design Contest

The design contest for the memorial was announced on December 7, 1988. Anyone over 18 could submit a design. The design had to include the existing Hemicycle and feature a visitors' center, auditorium, and computer room. The estimated cost was $15 million to $20 million.

The judging process was complex. A panel of architects, artists, and retired generals reviewed 139 entries. They looked for designs that honored women's service while respecting the Hemicycle's history.

After several rounds, four finalists were chosen. The winning design was by Michael A. Manfredi and Marion G. Weiss. Their design included 10 illuminated glass pyramids on top of the Hemicycle, representing challenges women faced in the military. An underground visitors' center with an auditorium and computer room would be accessed by stairs through the Hemicycle's niches.

The foundation hoped to start construction by November 1991. However, they had only raised about $700,000 of the needed $25 million.

Design Problems and Fundraising

The winning design needed approval from several government agencies. Unfortunately, the design was leaked to the media before it was officially submitted. This caused a lot of controversy. Many officials, including Senator John Warner, opposed the glass pyramids. They felt the pyramids were too tall and bright, and would block views or distract from other monuments like the Lincoln Memorial.

General Vaught was very upset, feeling the design didn't get a fair chance. With the design process stalled, she focused on raising money. By November 1991, the foundation had raised $4 million but spent $3 million, leaving only $1 million for construction. The congressional authorization for the memorial expired. However, Congress gave the foundation a two-year extension after they promised to get back on track with fundraising.

Building the Memorial

Getting the Design Approved Again

General Vaught worked closely with architects Weiss and Manfredi to change the design. In March 1992, they presented a new plan. The tall glass pyramids were gone. Instead, there were 108 horizontal glass panels on the Hemicycle's terrace, forming a skylight for the memorial below. These panels would have quotes from servicewomen etched into them. A thin stream of water would flow over the panels into a reflecting pool.

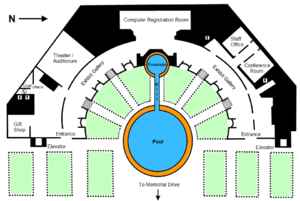

The underground visitors' center now included a curved gallery, a 250-seat auditorium, a computer room, and offices. The new design was praised by critics as "a significant addition" to the city's memorials.

The National Capital Memorial Advisory Commission approved the revised plan in May 1992. This approval helped with fundraising. The governments of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait each donated $850,000. The Commission of Fine Arts and the National Capital Planning Commission also approved the design in July 1992.

More Fundraising Efforts

By August 1992, the foundation still had only $1 million for construction. To help, First Lady of the United States Hillary Clinton and former First Lady Barbara Bush became honorary chairs.

In June 1993, the foundation started a new fundraising campaign by selling special commemorative coins. Congress approved the sale of silver and gold coins, with $10 from each coin going to the memorial. By March 1995, over half of the 500,000 coins had been sold, raising $2.7 million by June 1996.

The memorial's authorization expired again in November 1993. Congress granted another three-year extension. General Vaught also split the project into two parts: memorial construction and Hemicycle restoration. This allowed them to seek grants for preservation. By February 1994, the U.S. Air Force provided a $9.5 million grant to repair the Hemicycle.

Final Design Approval

The memorial design was presented again in October 1994. The architects made small changes, like recessing the steps in the niches. They also clarified that the skylight lighting would be a "soft glow" from below, not bright pylons. This convinced the CFA.

The CFA also discussed the plaza design. They wanted fewer trees and a more open space. The architects added more grass and made minor changes to the water feature. The fountain in the central niche would now have 200 jets of water shooting about 4 feet (1.2 meters) into the air.

With these revisions, the CFA gave its final approval on March 16, 1995. The National Capital Planning Commission gave its final approval on April 6.

Starting Construction

Groundbreaking for the memorial happened on June 22, 1995. To start, $15 million for construction had to be deposited. Major donations came from various veterans' groups. Since not all funds were raised, the foundation got a loan from a bank. Companies like AT&T and General Motors also donated.

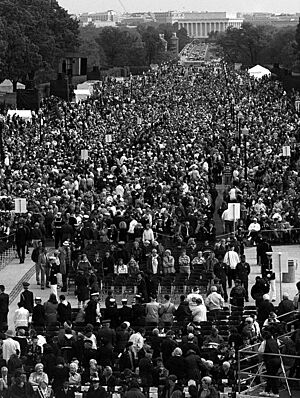

President Bill Clinton, First Lady Hillary Clinton, and other important people attended the ceremony, along with about 6,000 women veterans. Even though $6 million still needed to be raised, the foundation planned to dedicate the memorial in October 1997.

Building the Memorial

Clark Construction was hired as the main contractor. Construction began in January 1996. Workers removed a lot of soil and built the walls. They used over 25 tons of Yule marble for the interior walls, the same type of marble used for the Tomb of the Unknowns and Lincoln Memorial.

By February 1997, construction was halfway done. The terrace was almost complete, and frames for the glass panels were being installed. The last step was restoring the Hemicycle itself. This included cleaning the walls and installing the fountain, reflecting pool, and landscaping. The construction took almost two years and cost $21.5 million.

Many of the construction managers were women, including the on-site project manager, Margaret Van Voast.

Dedication Ceremony

As the October 17, 1997, dedication date approached, the memorial still needed money for exhibits and auditorium equipment. The foundation borrowed money to cover these costs. Because of money issues, only three exhibits were ready on dedication day, focusing mainly on women in World War II.

On October 11, 1997, the United States Postal Service announced a special stamp honoring the memorial. The stamp featured five women representing different military branches.

The dedication ceremonies began on October 16 with a candlelight march. On October 17, there was a wreath laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, followed by a ceremony at the Memorial Amphitheater. The main memorial ceremony included a fly-over by military aircraft, all piloted by women—a first in U.S. history. Speakers included Secretary of Defense William Cohen and Vice President Al Gore. President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton sent a video message.

A highlight was 101-year-old Frieda Mae Greene Hardin, a World War I veteran, who was escorted to the podium in her Navy uniform. About 30,000 people attended the ceremony.

What the Memorial Looks Like Today

The Military Women's Memorial covers 4.2 acres (1.7 hectares) at the entrance of Arlington National Cemetery. Visitors first see the Hemicycle, the grand gateway built in 1932. It is 30 feet (9 meters) high and 226 feet (69 meters) wide. In the center is an apse with the Great Seal of the United States carved above it. The seals of the U.S. Department of the Army and Navy are also visible. Six circular niches along the front are inlaid with red granite.

Rectangular doorways in the Hemicycle wall lead to stairways that go inside the memorial. A fountain with 200 water jets is in the center of the apse. The water flows down a channel into a circular reflecting pool, which holds 60,000 gallons (227,000 liters) of water. A plaza of light grey granite surrounds the fountain and pool.

The stairs inside the Hemicycle lead to the memorial's interior. Halfway up, visitors can look down into the main gallery. Continuing up leads to the Hemicycle's terrace.

On top of the Hemicycle is a terrace of light gray granite. Along the back of the terrace are 108 thick glass panels that form a skylight for the main gallery below. Many of these panels have quotes from servicewomen etched into them. Some panels are left blank for future inscriptions.

The 35,000 square foot (3,250 square meter) memorial is partly underground. The main gallery has 14 niches with displays about women in the U.S. armed forces. Eleven large glass tablets on the walls and ceiling have quotes from women veterans. Twelve computer terminals allow visitors to search a database of names and pictures of women who served from the American Revolutionary War to the War in Afghanistan.

Beyond the main gallery is the Hall of Honor. This room has displays honoring women who were prisoners of war, killed in action, or earned high awards. There is also a 196-seat theater where visitors can watch films about women's roles in the military. Each seat in the auditorium has a small brass plaque honoring a servicewoman. The memorial also has a gift shop, conference room, and offices.

On October 17, 2020, a bronze statue called "The Pledge" was unveiled in the memorial's lobby. It honors all women of the U.S. military.

Memorial Finances After Construction

General Vaught later admitted that the foundation was too hopeful about how easy it would be to raise money for the memorial's construction and ongoing costs.

To raise more funds, the foundation bought the remaining unsold commemorative coins from the U.S. Mint in November 1995 and sold them directly. By October 1997, coin sales had generated $3 million.

However, by September 1997, the memorial still needed $12 million to finish and to fund its operations. This included a $2.5 million shortfall for construction. Foundation officials said that a lack of interest from the defense industry, difficulty getting military records to contact women veterans, and general indifference to women's contributions led to fewer donations.

To pay its debts, the memorial relied on gift shop sales and other income. While Arlington National Cemetery gets millions of visitors, fewer than expected visited the memorial. By July 1998, annual revenues from the gift shop and other sources reached $5 million. The memorial also started charging for use of its space.

In January 1998, the memorial still owed about $2 million for construction. The construction company, Clark Construction, paid its subcontractors directly rather than waiting for payment from the memorial foundation. General Vaught said the financial situation was not serious, and they received some large donations after the dedication.

However, memorial finances remained unstable. In 2009, the memorial almost closed due to low revenue. Congress provided a $1.6 million grant to keep it open, and a fundraising drive brought in more money. By 2010, many World War II women veterans, who might have donated, had passed away or had limited incomes. A drop in gift shop sales after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the Great Recession also hurt finances.

On October 17, 2012, the Military Women's Memorial celebrated its 15th anniversary. Raising the $3 million needed for its yearly operating budget was still a challenge. In November 2016, the memorial was again at risk of closing due to financial difficulties.

Pylon Damage Lawsuit

During the memorial's construction, one of the 50-foot (15-meter) tall granite pylons next to the cemetery gate fell over on July 10, 1996. Workers were digging a trench nearby for utility lines. The pylon landed on soft earth, so it wasn't badly damaged, but the granite urn on top was destroyed. Engineers were surprised to find the pylon had no deep foundation or anchor.

A disagreement arose over which insurance company would pay for the repairs. The Hartford Fire Insurance Co. (Clark Construction's insurer) argued the pylons weren't covered. Montgomery Mutual Insurance Co. (Kalos Construction's insurer) paid the claim but then sued the Women in Military Service for America Memorial Foundation to get their money back.

The legal case went through several courts. Eventually, in 2000, a higher court ruled that the pylons were part of the existing structure and that The Hartford's policy should have covered them. The case was sent back to the lower court, which ruled in favor of Montgomery Mutual. The Hartford appealed again, but the appeals court upheld the decision, meaning Montgomery Mutual's payment was valid and The Hartford was responsible.