Zoran Đinđić facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zoran Đinđić

|

|

|---|---|

| Зоран Ђинђић | |

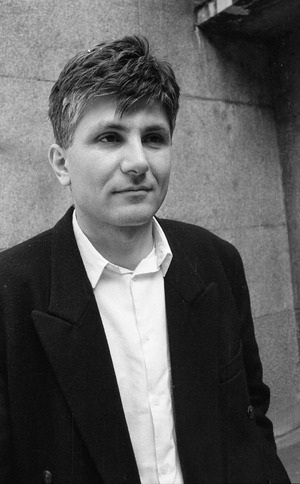

Đinđić in January 2003

|

|

| Prime Minister of Serbia | |

| In office 25 January 2001 – 12 March 2003 |

|

| President | Milan Milutinović Nataša Mićić (acting) |

| Preceded by | Milomir Minić |

| Succeeded by | Zoran Živković |

| 67th Mayor of Belgrade | |

| In office 21 February 1997 – 30 September 1997 |

|

| Preceded by | Nebojša Čović |

| Succeeded by | Vojislav Mihailović |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 August 1952 Bosanski Šamac, PR Bosnia and Herzegovina, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Died | 12 March 2003 (aged 50) Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Political party | DS (1990–2003) |

| Spouse |

Ružica Đinđić

(m. 1990) |

| Children | Jovana Luka |

| Alma mater | University of Belgrade University of Konstanz |

| Signature | |

Zoran Đinđić (Serbian Cyrillic: Зоран Ђинђић; 1 August 1952 – 12 March 2003) was an important Serbian politician. He served as the Prime Minister of Serbia from 2001 until his death in 2003. Before that, he was the Mayor of Belgrade in 1997. Đinđić was a strong supporter of democracy and had a special degree in philosophy.

He was one of the people who helped restart the modern Democratic Party in Serbia. He became its leader in 1994. In the 1990s, he was a key leader of the groups that opposed the government of Slobodan Milošević. After Milošević's government was overthrown, Đinđić became Prime Minister in 2001.

As Prime Minister, he worked to bring democratic changes to Serbia. He also wanted Serbia to join European groups and become closer to Europe. His government made sure human rights were protected and helped Serbia become a member of the Council of Europe in 2003. He also strongly supported working with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Đinđić was sadly killed in 2003.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Zoran Đinđić was born in Bosanski Šamac, which was part of Yugoslavia at the time. His father was a soldier, so his family moved often. Zoran spent ten years of his childhood in Travnik. Later, his family moved to the capital city, Belgrade.

He went to high school in Belgrade and then studied at the University of Belgrade. He finished his studies there in 1974. During his time at university, he became very interested in politics.

In 1974, he faced problems with the government for trying to start a student political group. A German leader named Willy Brandt helped him move to West Germany. There, Đinđić continued his studies and earned a special degree in philosophy in 1979 from the University of Konstanz. He learned that smart people should not just think, but also act. He became very good at speaking German and later, English.

Political Career

In 1979, Đinđić came back to Yugoslavia and started teaching at the University of Novi Sad. In the 1980s, he wrote for an important magazine in Belgrade called Literary Review. In Serbia, smart people were highly respected because they helped keep the national culture and identity alive.

In 1989, Zoran Đinđić helped create the Democratic Party (DS). This party was based on an older party that existed in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He quickly became a leader in the party and was elected to the Parliament of Serbia that same year. In 1994, he became the president of the Democratic Party.

In November 1996, his party joined other opposition groups to form a coalition called "Zajedno" (Together). They won local elections in major Serbian cities like Belgrade, Niš, and Novi Sad. However, the government leader, Slobodan Milošević, did not accept the results. This led to three months of huge protests by hundreds of thousands of people. Because of the protests, Milošević had to accept the results. On 21 February 1997, Đinđić became the Mayor of Belgrade. He was the first mayor of Belgrade after World War II who was not from the communist party.

Later that year, the "Zajedno" coalition broke apart. Đinđić decided that his party would not take part in the parliamentary elections in December 1997. This meant that Milošević's party and its allies won most of the seats.

When NATO's war against Yugoslavia began in 1999, Đinđić went to Montenegro for safety.

In September 1999, Time magazine called Đinđić one of the most important politicians for the new century. When he returned to Serbia in July 1999, he was accused of threatening state security. The trial was held in secret and was later found to be unfair.

Đinđić played a big role in the uprising in October 2000 that removed Milošević from power. He led a large group of 19 opposition parties called the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS). This group won a big victory in the December 2000 elections. The Democratic Party was the largest party in this group. On 25 January 2001, Zoran Đinđić became the Prime Minister of Serbia. This was the first government after Milošević.

On 1 April 2001, former president Slobodan Milošević was arrested. The United States wanted Milošević to be sent to the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia). If he wasn't sent, Serbia would lose financial help from international organizations. The president at the time, Vojislav Koštunica, did not want to send Milošević, saying it was against the law. But Prime Minister Đinđić believed it was important to cooperate. He ordered Milošević to be sent to The Hague on 28 June 2001. After this, Yugoslavia received about $1 billion in financial aid.

Western countries liked Đinđić and his policies. He met with leaders like George W. Bush, Tony Blair, and Jacques Chirac, which showed they supported him. Đinđić often disagreed with his political rival, Vojislav Koštunica.

As Prime Minister, Đinđić also worked on improving Serbia's economy. He made prices more open and tried to control money supply to make the economy stable. He also started selling off small state-owned businesses and banks to private owners. His government also removed many trade barriers to help Serbia join the European Union. These economic changes helped the economy grow a lot before 2008.

In early 2003, Đinđić started a major effort to find a solution for the Kosovo region. He also spoke about an idea to create a union of Serb states, including Serbia, Montenegro, and Republika Srpska.

Assassination

Zoran Đinđić was killed in Belgrade on 12 March 2003. He was shot by Zvezdan Jovanović, a former soldier. He was taken to a hospital but died an hour later.

On 23 May 2007, twelve men were found guilty of his assassination. Some of these men are still wanted by the police.

Personal Life

Zoran Đinđić and his wife Ružica had a daughter named Jovana and a son named Luka. They were both children when he was killed.

Legacy

His funeral was held on 15 March 2003, and hundreds of thousands of people attended, along with leaders from other countries. Many Serbs saw Đinđić's death as a great loss. They believed he was a leader who offered peace with neighboring countries, a way for Serbia to join Europe and the rest of the world, and a brighter future with a better economy. He inspired people in Serbia who wanted their country to become more like Western nations.

Images for kids

-

Tomb of Đinđić on the Alley of Meritorious Citizens, New Cemetery in Belgrade

See also

In Spanish: Zoran Đinđić para niños

In Spanish: Zoran Đinđić para niños