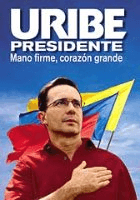

Álvaro Uribe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Álvaro Uribe

|

|

|---|---|

Uribe in 2010

|

|

| 31st President of Colombia | |

| In office 7 August 2002 – 7 August 2010 |

|

| Vice President | Francisco Santos Calderón |

| Preceded by | Andrés Pastrana Arango |

| Succeeded by | Juan Manuel Santos |

| Senator of Colombia | |

| In office 20 July 2014 – 18 August 2020 |

|

| In office 20 July 1986 – 20 July 1994 |

|

| Governor of Antioquia | |

| In office 1 January 1995 – 1 January 1998 |

|

| Preceded by | Ramiro Valencia |

| Succeeded by | Alberto Builes Ortega |

| Mayor of Medellín | |

| In office October 1982 – December 1982 |

|

| Appointed by | Álvaro Villegas Moreno |

| Preceded by | Jose Jaime Nicholls Sánchez |

| Succeeded by | Juan Felipe Gaviria Gutierrez |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Álvaro Uribe Vélez

4 July 1952 Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia |

| Political party | Liberal (1977–2001) Colombia First (2001–2010) Social Party of National Unity (2010–2013) Democratic Center (2013–present) |

| Spouse |

Lina María Moreno Mejía

(m. 1979) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | University of Antioquia |

| Awards |

|

| Signature |  |

Álvaro Uribe Vélez (born 4 July 1952) is a Colombian politician. He served as the 31st President of Colombia from 2002 to 2010.

Uribe began his political journey in his home region of Antioquia. He worked in public services and the Ministry of Labor. He also directed the Special Administrative Unit of Civil Aeronautics from 1980 to 1982. In October 1982, he became the Mayor of Medellín.

Later, he served as a Senator of Colombia from 1986 to 1994. He then became the Governor of Antioquia from 1995 to 1997. In 2002, he was elected President of Colombia.

During his presidency, Uribe focused on improving security in Colombia. He worked to reduce the power of armed groups like the FARC and the ELN. He also aimed to disarm the AUC. These groups were involved in the Colombian Armed Conflict. His time in office saw efforts to bring more peace and order to the country.

After leaving the presidency in 2010, Uribe continued to be active in politics. In 2012, he helped start a new political group called the Democratic Center. He was elected as a senator again in 2014. He served in the Senate until 2020.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Álvaro Uribe was born in Medellín on July 4, 1952. He was the oldest of five children. His father, Alberto Uribe, owned land. When Álvaro was 10, his family moved from their ranch in Salgar to Medellín. He finished high school in 1970.

Uribe studied law at the University of Antioquia and graduated in 1977. After his father passed away, Uribe focused more on his political career. He joined the Colombian Liberal Party.

In 1993, he attended Harvard University. He earned certificates in administration, management, negotiation, and dispute resolution. Later, from 1998 to 1999, he studied at St Antony's College, Oxford, in England. He received a special scholarship for his studies there.

Uribe married Lina María Moreno Mejía in 1979. They have two sons, Tomás and Jerónimo.

Political Journey

In 1976, at just 24 years old, Uribe became the Chief of Assets for the Public Utilities of Medellín. From 1977 to 1978, he served as the Secretary General of the Ministry of Labor. In 1980, he was named Director of Civil Aviation. He held this position until 1982.

Senator of Colombia

Uribe was elected as a senator for Antioquia. He served two terms, from 1986 to 1990 and again from 1990 to 1994. As a senator, he worked on laws about pensions, labor, and social security. He also supported laws to promote administrative careers and protect women. During his time, he was recognized as one of the "best senators."

Governor of Antioquia

From 1995 to 1997, Uribe was the governor of the Antioquia region. During his term, he worked on a plan he called a "communitarian state." This idea aimed to involve citizens more in government decisions. The goal was to improve jobs, education, and public safety.

He supported a national program for private security services known as CONVIVIR. These groups were meant to help improve security.

2002 Presidential Election

Uribe ran for president as an independent candidate. His main promise was to strongly address Colombia's armed groups, especially the FARC. He also wanted to cut government spending and fight corruption.

Before Uribe, President Andres Pastrana had tried to make peace with the FARC. However, these talks did not lead to a cease-fire, and violence continued. Many people were unhappy with the main political parties. Uribe was seen as a candidate who could offer a strong security plan.

Uribe won the election in the first round on May 26, 2002, with 53% of the votes. His running mate was Francisco Santos Calderón. Observers generally saw the elections as fair.

Presidency (2002–2010)

Internal Security

During his time as president, Uribe's main goal was to control or defeat the armed groups in Colombia. These included the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), National Liberation Army (ELN), and FARC. By the end of his first term, many AUC members agreed to disarm.

Uribe believed the government needed to show its strength first. This would encourage armed groups to negotiate for peace later. He stated that peace was essential for investment, which would then provide money for public welfare.

His security plan, called "democratic security," aimed to:

- Bring back police presence to all towns.

- Increase legal action against serious crimes.

- Make public institutions stronger.

- Reduce human rights violations.

- Break up armed rebel groups like the FARC-EP.

- Lower kidnappings and extortion.

- Reduce crime rates.

- Prevent people from being forced to leave their homes and help them return.

To achieve these goals, the plan focused on:

- Getting more citizens involved.

- Supporting soldiers.

- Improving intelligence gathering.

- Taking back control of national roads.

- Disarming illegal groups.

- Working together with all armed forces.

- Increasing money spent on defense.

In 2002, Uribe's government introduced a special tax to raise money for security. This tax helped collect more than expected. The goal was also to increase defense spending.

Official government data from August 2004 showed that in two years, homicides, kidnappings, and terrorist attacks dropped by about 50%. This was the lowest level in nearly 20 years. By April 2004, police or military were present in every Colombian town, which had not happened in decades.

A report from the United Nations in February 2005 noted improvements in human rights and international humanitarian law. However, it also pointed out that some weaknesses remained.

After some AUC leaders agreed to a cease-fire, thousands of their fighters disarmed in late 2004. The main AUC leaders continued talks with the government. Some paramilitary units did not disarm and continued criminal activities. These groups became known as the Black Eagles.

The Colombian Congress passed the Justice and Peace Law. This law allowed paramilitary leaders to receive shorter prison sentences if they confessed to their crimes and provided information.

International Relations

Uribe was a supporter of the US war on terror. He maintained good relationships with Spain and most Latin American countries. He signed agreements with nations like Venezuela, Bolivia, and China.

Despite different political views, Uribe met with leaders like Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and Lula da Silva of Brazil. Colombia also kept diplomatic ties with Cuba and China.

Colombia worked with many countries, including the US, Spain, and its neighbors, to fight crime. Uribe's government also negotiated free trade agreements with the US and Mercosur.

On July 2, 2008, Colombian Special Forces carried out a secret rescue mission called Operation Jaque. They rescued Senator Ingrid Betancourt, three Americans, and eleven Colombian soldiers and police officers. This operation was done without bloodshed and made Uribe even more popular.

Uribe's main challenge in 2007 was dealing with the humanitarian exchange situation. The FARC held many hostages, including Ingrid Betancourt. Uribe tried different ways to free them, including military rescues and asking other countries to help.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez also tried to help mediate with the FARC. However, Uribe ended the mediation after Chávez spoke with Colombian military leaders without permission. This led to tensions between the two presidents.

A regional crisis began in March 2008 when Colombian troops killed a FARC commander in Ecuador. Ecuador, Venezuela, and Nicaragua broke off diplomatic ties with Colombia. Uribe put his armed forces on high alert.

The crisis was resolved at a summit in the Dominican Republic. Leaders from the region, including Uribe, met and agreed to restore relations.

Economic Policy

Uribe's government worked with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. They secured loans and agreed to manage expenses and debt. The government also privatized some public companies.

Companies like Carbocol and Telecom Colombia were restructured or privatized. This was done to make them more efficient or because they were too expensive to maintain.

Some critics believed Uribe's economic policies favored private and foreign investors. They argued that these policies did not fully address poverty and unemployment. Unions also claimed that privatizations hurt national industries.

Unemployment remained high during Uribe's presidency, staying between 11% and 12%.

Reelection and Popularity

In 2004, Uribe's supporters in Congress changed the Colombian Constitution of 1991. This allowed him to run for a second term as president. Before this, presidents could only serve one four-year term. Uribe was re-elected on May 28, 2006, for his second term (2006–2010). He became the first president in over a century to be re-elected in Colombia. He won with about 62% of the vote, which was a large victory.

The Organization of American States (OAS) sent observers to the elections. They stated that the elections were "free, transparent and normal."

Uribe's approval ratings were generally high during his presidency. They often stayed between 60% and 70%. In June 2008, after Operation Jaque, his approval rating reached 91%. By May 2009, it had dropped to 68%. When he left office, his popularity was still very high, between 79% and 84%.

2010 Third Term Proposal

As Uribe's second term was ending, his supporters tried to amend the constitution again. They wanted to allow him to run for a third term.

In May 2009, Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos resigned. He planned to run for president if Uribe could not or would not seek a third term.

Congress supported a proposed referendum for a third term. However, the Constitutional Court rejected it in February 2010. The Court found problems with how signatures were collected for the referendum. It also said the law allowing the referendum was against democratic principles. Uribe said he would respect the Court's decision.

The Constitutional Court also ruled that Colombian presidents could only serve two terms, even if they were not consecutive. This meant Uribe could not run for president again in 2014. The Constitution has since been changed to limit the president to a single four-year term.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Álvaro Uribe Vélez para niños

In Spanish: Álvaro Uribe Vélez para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |