Aikido facts for kids

One version of shihōnage where the attacker (uke) is standing and the defender (nage) sitting. This is called hanmi-handachi. The uke is being thrown, and is taking a breakfall (ukemi) to safely reach the ground.

|

|

| Focus | Grappling |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | Morihei Ueshiba |

| Famous practitioners | Kisshomaru Ueshiba, Moriteru Ueshiba, Steven Seagal, Christian Tissier, Morihiro Saito, Koichi Tohei |

| Parenthood | Aiki-jūjutsu; Jujutsu; Kenjutsu; Sōjutsu, Bojutsu, Iaijutsu |

Aikido (合気道, aikidō) /eye-Kee-doh/ is a Japanese martial art. It was created by Morihei Ueshiba.

Aikido is based on Ueshiba's ideas, his martial arts training, and his spiritual beliefs. The word "aikido" often means "the way of unifying with life energy" or "the way of harmonious spirit." Ueshiba wanted to create a martial art where people could defend themselves without hurting their attacker. They would do this by using the attacker's "ki" (life energy) against them. He hoped that everyone who practiced Aikido would grow stronger both physically and mentally.

Aikido is performed by moving with the attacker's actions. Instead of fighting against their force, you use it. This means you don't need a lot of physical strength. An aikidōka (someone who does Aikido) uses the attacker's own momentum. They do this with special stepping and turning movements. Aikido techniques often end with throws or joint locks. These can be combined with different ways to defend yourself. Aikido is one of many grappling arts.

Aikido grew from the martial art of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. It started to become its own art in the late 1920s. This was partly because Ueshiba was involved with the Ōmoto-kyō religion. Early students of Ueshiba called it aiki-jūjutsu. Today, Aikido is practiced all over the world. There are many different styles, and groups focus on different things. However, they all use techniques taught by Ueshiba. Most styles also care about keeping the attacker safe during practice.

Contents

How Do You Train in Aikido?

In Aikido, like most Japanese martial arts, training involves both your body and your mind. The physical training in Aikido is varied. It includes general fitness and special exercises. A big part of Aikido training involves throws. Because of this, beginners learn how to fall or roll safely. This is called ukemi.

You learn techniques for both attacking and defending. Attacks include strikes and grabs. Defenses include throws and pins. After learning the basic moves, students practice defending against several opponents. They also learn techniques with weapons.

What Are the Basic Attacks in Aikido?

Aikido techniques are usually defenses against an attack. So, students must learn how to perform different attacks. This helps them practice Aikido with a partner. Attacks are not studied as deeply as in arts that focus on striking. But strong attacks are needed to learn how to use techniques correctly.

Many strikes (打ち, uchi) in Aikido look like cuts from a sword. This shows that Aikido came from fighting with weapons. Other moves, which look like punches (tsuki), are practiced like thrusts with a knife or sword. Kicks are usually for advanced students. This is because falling from kicks can be dangerous. Also, kicks were not common in feudal Japan.

Some basic strikes include:

- Front-of-the-head strike (正面打ち, shōmen'uchi): A vertical knifehand strike to the head. In training, this is aimed at the forehead for safety.

- Side-of-the-head strike (横面打ち, yokomen'uchi): A diagonal knifehand strike to the side of the head or neck.

- Chest thrust (胸突き, mune-tsuki): A punch to the torso. This can be aimed at the chest or abdomen.

- Face thrust (顔面突き, ganmen-tsuki): A punch to the face.

Beginners often practice techniques from grabs. This is because grabs are safer. It is also easier to feel the direction of force from a grab than from a strike. Some grabs come from being held while trying to pull out a weapon. Then, a technique could be used to get free and control the attacker.

Here are some basic grabs:

- Single-hand grab (片手取り, katate-dori): When one hand grabs one wrist.

- Both-hands grab (諸手取り, morote-dori): When both hands grab one wrist.

- Both-hands grab (両手取り, ryōte-dori): When both hands grab both wrists.

- Shoulder grab (肩取り, kata-dori): When one shoulder is grabbed.

- Both-shoulders-grab (両肩取り, ryōkata-dori): When both shoulders are grabbed.

- Chest grab (胸取り, mune-dori or muna-dori): When the lapel (collar) is grabbed.

What Are the Main Aikido Techniques?

Here are some of the main throws and pins in Aikido. Many of these techniques come from Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. Some were created by Morihei Ueshiba himself. The names might be slightly different in various schools. The ones listed here are used by the Aikikai Foundation. Even though they have numbers, they are not always taught in that order.

- First technique (一教 (教), ikkyō): A control technique. One hand is on the elbow, the other near the wrist. This helps bring uke (the attacker) to the ground.

- Second technique (二教, nikyō): A wristlock that twists the arm and puts pressure on nerves.

- Third technique (三教, sankyō): A rotational wristlock. It creates twisting tension through the arm, elbow, and shoulder.

- Fourth technique (四教, yonkyō): A shoulder control technique. It is similar to ikkyō. Both hands grip the forearm, pressing knuckles against a nerve.

- Fifth technique (五教, gokyō): Looks like ikkyō. But it uses a different grip on the wrist and twists the arm inward. This is common for taking away a knife.

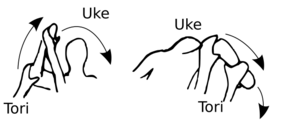

- 'Four-direction throw' (四方投げ, shihōnage): A throw where uke's hand is folded back past the shoulder, locking the shoulder joint.

- Forearm return (小手返し, kotegaeshi): A wristlock-throw that stretches the forearm muscles.

- Breath throw (呼吸投げ, kokyūnage): A general term for many different throws. These throws usually don't use joint locks like other techniques.

- Entering throw (入身投げ, iriminage): Throws where tori (the defender) moves into the space where uke is.

- Heaven-and-earth throw (天地投げ, tenchinage): A throw that starts with both wrists grabbed (ryōte-dori). tori sweeps one hand low ("earth") and the other high ("heaven"). This makes uke lose balance and fall easily.

- Hip throw (腰投げ, koshinage): Aikido's version of the hip throw. tori lowers their hips below uke's. Then they flip uke over their hip.

- Figure-ten throw (十字投げ, jūjinage): A throw that locks the arms together. The kanji for "10" (十) looks like a cross.

- Rotary throw (回転投げ, kaitennage): A throw where tori sweeps uke's arm back. It locks the shoulder joint. Then, forward pressure is used to throw them.

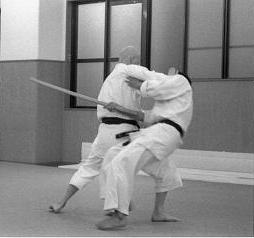

Do Aikido Practitioners Use Weapons?

Yes, traditional Aikido training includes weapons. These are the short staff (jō), the wooden sword (bokken), and the knife (tantō). Some schools also teach how to disarm someone with a firearm.

The founder, Morihei Ueshiba, created many empty-handed techniques from sword, spear, and bayonet movements. So, practicing with weapons helps you understand where the techniques come from. It also helps you learn about distance, timing, footwork, and connecting with your training partner.

How Does Aikido Help Your Mind?

Aikido training is not just physical; it's also mental. It teaches you to keep your mind and body calm, even in tough situations. This calmness helps you perform the "enter-and-blend" movements that are key to Aikido. It means facing an attack with confidence. Morihei Ueshiba once said you "must be willing to receive 99% of an opponent's attack and stare death in the face." This helps you do techniques without hesitation. Since Aikido is about improving daily life, this mental part is very important for those who practice it.

What Do Aikido Practitioners Wear and What Are the Ranks?

| rank | belt | color | type |

|---|---|---|---|

| kyū | white | mudansha/yūkyūsha | |

| dan | black | yūdansha |

Aikido practitioners (often called aikidōka) move up through a series of "grades" (kyū). After that, they move through "degrees" (dan). You usually take tests to get promoted.

Some Aikido groups use belts to show a person's grade. Often, white belts are for kyu grades, and black belts are for dan grades. Some schools use different colored belts. The requirements for testing can be different, so a rank in one school might not be the same as in another. Some dojos (training halls) require students to be a certain age before they can test for a dan rank.

The uniform for Aikido (aikidōgi) is like uniforms in other modern martial arts. It has simple trousers and a jacket that wraps around. It's usually white. You can use thick ("judo-style") or thin ("karate-style") cotton tops. Some Aikido tops have shorter sleeves that reach just below the elbow.

Most Aikido styles also use a pair of wide, pleated black or indigo trousers called hakama. These are also used in other Japanese martial arts like Naginatajutsu, kendo, and iaido. In many schools, only students with dan ranks or instructors wear a hakama. But other schools let all students wear one, no matter their rank.

Why Are There Different Aikido Styles?

Aikido styles can be different because Aikido is a very broad art. The main differences you might see are in how intense and realistic the training is. Some people have pointed out that sometimes the attacks from uke (the attacker) are not strong enough. This can make it harder for tori (the defender) to learn real self-defense skills.

To fix this, some styles let students become less cooperative over time. But this happens only after they show they can protect themselves and their partners safely. Shodokan Aikido even uses a competitive format. These changes are debated among different styles. Some believe their methods don't need to change. They argue that criticisms are wrong, or that they are not training for combat. Instead, they focus on spiritual growth, fitness, or other reasons.

The differences in Aikido teachings come from a shift in focus after Ueshiba lived in Iwama from 1942 to the mid-1950s. During this time, he focused more on the spiritual and philosophical parts of Aikido. Because of this, things like striking vital points, initiating techniques, the difference between omote (front side) and ura (back side) techniques, and using weapons became less important or were removed from practice in some schools.

On the other hand, some Aikido styles don't focus as much on the spiritual practices Ueshiba emphasized. According to Minoru Shibata of Aikido Journal:

O-Sensei's aikido was not a continuation and extension of the old and has a distinct discontinuity with past martial and philosophical concepts.

This means that Aikido practitioners who focus on its roots in traditional jujutsu or kenjutsu might be moving away from what Ueshiba taught. Some critics encourage practitioners to remember:

[Ueshiba's] transcendence to the spiritual and universal reality were the fundamentals of the paradigm that he demonstrated.

Images for kids

-

Ikkyo, first principle established between the founder Sensei Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平) (December 14, 1883 – April 26, 1969) and André Nocquet (30 July 1914 – 12 March 1999) disciple.

See also

In Spanish: Aikidō para niños

In Spanish: Aikidō para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |