Waterwheel plant facts for kids

The waterwheel plant (scientific name: Aldrovanda vesiculosa) is a special kind of flowering plant. It's the only living species in its group, called Aldrovanda, and it belongs to the Droseraceae family. This plant is a meat-eater! It catches tiny water creatures, like insects, using traps that work a bit like the famous Venus flytrap. Its traps grow in circles around a central stem, which makes it look like a wheel, giving it the name "waterwheel plant." It's one of the few plants that can move really fast!

Quick facts for kids Waterwheel plant |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Aldrovanda

|

| Species: |

vesiculosa

|

|

|

| Distribution | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Even though there's only one type of waterwheel plant alive today, scientists have found fossils of about 19 other kinds that are now extinct. The A. vesiculosa plant looks a bit different depending on where it grows, but all waterwheel plants around the world have very similar genes.

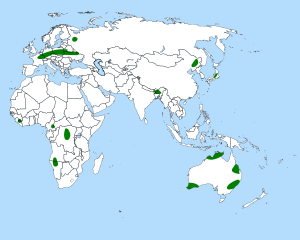

Sadly, the waterwheel plant has become much rarer over the last 100 years. Now, there are only about 50 known groups of them left in the wild. These can be found in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. However, some groups in the eastern United States might be invasive, meaning they could cause problems for local plants and animals. People who love plants often grow the waterwheel plant as a hobby.

Contents

What the Waterwheel Plant Looks Like

The waterwheel plant is a special aquatic plant that floats in water and doesn't have roots. When it's a seedling, it grows a small root, but this root doesn't grow much and soon dies off. The plant has floating stems that can be anywhere from 6 to 40 centimeters (about 2 to 16 inches) long.

Its tiny trap leaves, which are only 2 to 3 millimeters (about 1/16 of an inch) big, grow in circles along the main stem. Each circle has 5 to 9 leaves. The traps themselves are attached to stalks that have air sacs, which help the plant float. One end of the stem keeps growing, while the other end slowly dies away. This plant grows very quickly, sometimes 4 to 9 millimeters (about 1/4 to 3/8 of an inch) each day in places like Japan. This means a new circle of leaves can appear every day or even more often if conditions are perfect.

How the Traps Work

The traps of the waterwheel plant are made of two parts that fold together, just like a Venus flytrap. But these traps are smaller and are found underwater. They are twisted so their openings face outwards. Inside, the traps have tiny trigger hairs. When a small water creature touches these hairs, the trap snaps shut very quickly, catching the creature inside.

The trap closes in just 10 to 20 milliseconds, which makes it one of the fastest movements in the entire plant kingdom! This amazing trapping action only happens when the water is warm, at least 20°C (68°F). Each trap also has four to six long bristles, about 6 to 8 millimeters (about 1/4 to 3/8 of an inch) long, around it. These bristles help stop the trap from closing by accident if something like a piece of debris bumps into it.

Waterwheel Plant Reproduction

Flowers and Seeds

The waterwheel plant has small, white flowers that grow on short stalks above the water. Each flower only opens for a few hours. After it closes, the flower goes back underwater to make seeds. The seeds are special because their first leaves (called cotyledons) stay hidden inside the seed coat. These hidden leaves store energy for the new seedling to grow.

However, it's rare for waterwheel plants to flower in cooler places, and even when they do, they often don't produce many fruits or seeds.

Making New Plants by Dividing

The waterwheel plant usually makes new plants by simply dividing itself. When conditions are good, an adult plant will grow a new shoot every 3 to 4 centimeters (about 1 to 1.5 inches). As the plant keeps growing at the tips, the older parts die off and break away, forming new, separate plants. Because this plant grows so fast, many new plants can be made in a short time this way.

Winter Survival: Turions

To survive the cold winter, waterwheel plants that live in places with frost form special buds called turions. When winter starts, the plant's growing tip stops making regular leaves and instead produces very small, non-meat-eating leaves on a much shorter stem. This creates a tight bud of protective leaves. This bud becomes heavier and releases gases that help the plant float, so it sinks to the bottom of the water.

At the bottom, the water stays warmer and more stable, allowing the turion to survive temperatures as low as -15°C (5°F). In nature, not all turions successfully sink. Those that don't sink might be eaten by water birds or killed by the frost. In spring, when the water warms up to 12-15°C (54-59°F), the turions become less dense and float back to the surface. There, they start to grow into new plants. Sometimes, turion-like parts can also form in summer if there's a drought.

Where the Waterwheel Plant Lives

The waterwheel plant is the second most widespread carnivorous plant in the world, after the bladderwort. It naturally grows in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. Waterwheel plants mostly spread when water birds carry them. The plants can stick to a bird's feet and then be dropped off at the next pond or lake the bird visits. This is why most waterwheel plant groups are found along the paths that birds take when they migrate.

Over the last century, this plant has become much rarer and is now considered extinct in many countries. In the 1970s, plant enthusiasts brought this species to small ponds in the United States, in places like New Jersey, Virginia, and the Catskills in New York. These introduced plants might become invasive species because they can affect the tiny water creatures that live there.

Waterwheel Plant Habitat

A. vesiculosa likes clean, shallow, warm, still water that has lots of light. It prefers water with low nutrients and a slightly acidic pH (around 6). You can find it floating among plants like rushes, reeds, and even rice plants.

History of the Waterwheel Plant

The waterwheel plant was first written about in 1696 by Leonard Plukenet. He based his description on plants collected in India and called it Lenticula pulustris Indica. The name we use today comes from Gaetano Lorenzo Monti, who described plants from Italy in 1747. He named them Aldrovandia vesiculosa to honor an Italian naturalist named Ulisse Aldrovandi. Later, when Carl Linnaeus published his book Species Plantarum in 1753, the "i" was accidentally dropped from the name, creating the modern scientific name.

Images for kids

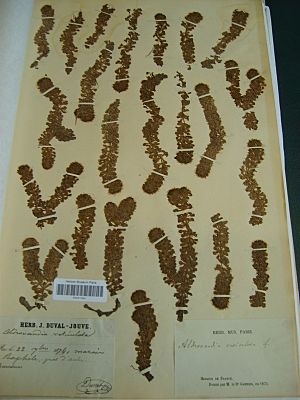

-

Herbarium specimens (dried plants for study) at the Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris

See also

In Spanish: Aldrovanda vesiculosa para niños

In Spanish: Aldrovanda vesiculosa para niños