Aldus Manutius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aldus Manutius

|

|

|---|---|

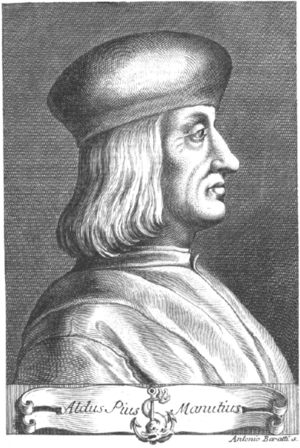

Aldus Pius Manutius, illustration in Vita di Aldo Pio Manuzio (1759)

|

|

| Born |

Aldo Manuzio

c. 1449/1452 Bassiano (near Rome), Papal States

|

| Died | 6 February 1515 |

| Other names | Aldus Manutius the Elder |

| Occupation | Renaissance humanist, printer, publisher |

| Known for | Founding the Aldine Press at Venice Founding the New Academy |

Aldus Pius Manutius (born around 1449/1452 – died February 6, 1515) was an Italian printer and scholar. He founded the Aldine Press in Venice. Aldus spent the last part of his life printing and sharing rare books. He was very interested in preserving old Greek writings. This made him a very important publisher of his time. His small, portable books, called enchiridia, changed how people read. They were like the first paperback books we have today.

Manutius wanted to print books in Greek because he believed that works by famous thinkers like Aristotle were best in their original form. Before him, it was hard to print Greek books because there wasn't a good way to make Greek letters. Manutius printed rare books in their original Greek and Latin forms. He also created new styles of letters, called typefaces. These typefaces looked like the handwriting of scholars back then. They were the first known examples of what we now call italic type. As his printing company, the Aldine Press, became popular, others quickly copied his ideas, even though he tried to stop them.

The Aldine Press became known for printing very careful and accurate books. Because of this, the famous Dutch philosopher Erasmus asked Manutius to publish his translations of a play called Iphigenia in Aulis.

When he was young, Manutius studied in Rome to become a scholar. He was friends with Giovanni Pico and taught Pico's nephews. Later, in his late thirties or early forties, Manutius moved to Venice to become a printer. There, he met Andrea Torresano, and they started the Aldine Press together.

Manutius is also known as "Aldus Manutius the Elder" to tell him apart from his grandson, Aldus Manutius the Younger.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Aldus Manutius was born near Rome in Bassiano between 1449 and 1452. He grew up in a wealthy family during the Italian Renaissance. When he was young, he went to Rome to become a scholar. In Rome, he studied Latin and Greek.

Most of Manutius's early life is not well known. He became a citizen of Carpi in 1480. In 1482, he traveled to Mirandola to study Greek literature with his friend, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. Pico later suggested Manutius become a tutor for his nephews, Alberto and Leonello Pio. In Carpi, Manutius became close with his student, Alberto Pio. Manutius published two books for his students and their mother.

The families of Giovanni Pico and Alberto Pio helped Manutius start his printing press. Manutius decided that Venice was the best place for his work, so he moved there in 1490. In Venice, he started getting printing jobs. He met Andrea Torresano, who was also a printer. Torresano and Manutius became business partners for life. For their first job, Manutius hired Torresano to print his Latin grammar book in 1493.

The Aldine Press

The Aldine Press started in 1494. Its first book was published in March 1495. Andrea Torresano and Pier Francesco Barbarigo, who was the nephew of the Doge, each owned half of the company. Manutius owned a part of Torresano's share.

The press's first big success was a five-volume set of books by Aristotle. Manutius started the first volume in 1495. The other four volumes were published in 1497 and 1498. The Aldine Press also printed nine comedies by Aristophanes in 1498. Pietro Bembo helped edit Petrarch's poems, which Manutius published in 1501. Besides editing Greek books, Manutius also fixed and improved texts that were first printed in other cities.

A war, called the Second Italian War, stopped the press for a while. During this time, Desiderius Erasmus asked Manutius to publish his translations of two plays, Hecuba and Iphigenia in Aulis. Erasmus and Manutius agreed to work together. In December 1507, the Aldine Press published Iphigenia in Aulis. It was a small, 80-page book with Erasmus's translation from Greek to Latin.

Because their first project was so successful and accurate, Manutius agreed to publish a bigger version of Erasmus's collection of sayings. Erasmus traveled to Venice and worked at the Aldine Press for ten months. He lived in Manutius and Torresano's home. His research, using Manutius's books and Greek scholars, helped him expand his collection of sayings from 819 to 3,260. The Aldine Press published this new collection, Adagiorum Chiliades, in 1508. After this, Erasmus helped Manutius check a Greek edition of Plutarch's Moralia and other books.

Manutius worked with Greek scholars like Marcus Musurus to translate books for the Aldine Press. He published books by Greek speakers in 1508 and works by Plutarch in 1509. Printing stopped again because of another conflict. Manutius started printing again in 1513 with a book by Plato. He wrote a special message in it to Pope Leo X, comparing the troubles of war with the peaceful life of a student.

As the Aldine Press became more popular, many people visited the shop, which interrupted Manutius's work. He put up a sign that said, "Whoever you are, Aldus asks you again and again what it is you want from him. State your business briefly and then immediately go away."

Manutius wanted his books to have excellent typography (the style and appearance of printed matter) and design. He also wanted to make them more affordable. He faced many challenges, like worker strikes, rivals copying his materials, and frequent wars.

Greek Classics

Before Manutius, there were very few Greek books printed. Most had to be brought in from one specific press in Milan. Only four Italian towns were allowed to print Greek books, and they only published works by a few authors. Some printers even left blank spaces for Greek letters to be filled in by hand later.

Manutius wanted to "inspire and improve his readers by filling their hands with Greek books." He came to Venice because it had many Greek resources. Venice had Greek writings from the time of Constantinople and many Greek scholars from Crete. Also, in 1468, a cardinal had given his large collection of Greek writings to Venice. To save ancient Greek literature, the Aldine Press created a typeface that looked like old Greek handwriting. This way, readers could experience the original Greek text more truly.

While printing Greek books, Manutius started the New Academy in 1502. This was a group of scholars who loved Greek studies. The rules of the New Academy were written in Greek, and its members spoke Greek. Famous members included Desiderius Erasmus. Manutius spoke Greek at home and hired thirty Greek speakers at the Aldine Press. Greek speakers from Crete prepared and checked the books. Instructions for workers were written in Greek, and the introductions to Manutius's books were also in Greek. The Aldine Press published 75 books by famous Greek and Byzantine writers.

Latin and Italian Classics

Besides Greek classics, the Aldine Press also published books by Latin and Italian authors. Manutius helped start Pietro Bembo's career by publishing his book De Aetna in 1496. This was the first Latin book by a living author that the Aldine Press published. The Bembo family hired the Aldine Press to print accurate versions of books by Dante and Petrarch. Pietro Bembo worked with Manutius from 1501 to 1502 to create accurate editions of Dante and Petrarch. He also helped add punctuation to these books.

Manutius did not have as many new ideas for Latin classics as he did for Greek ones. This was because Latin books had been printed for 30 years before his time. To promote his Latin books, Manutius wrote about their high quality in his introductions. Manutius always looked for rare old books. He often found missing parts of books that had been printed before. For example, he published missing parts of a work by Valerius Maximus that someone found in a manuscript in Vienna.

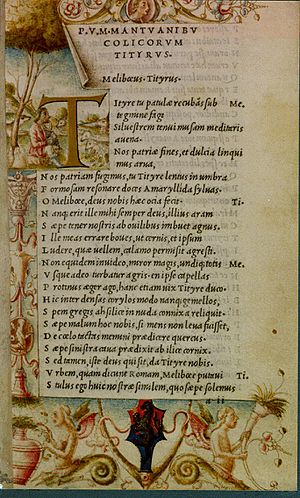

The press printed first editions of works by Poliziano, Pietro Bembo, Francesco Colonna's Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, and Dante's Divine Comedy. The 1501 printing of Virgil was the first to use italic print. More copies of this book were printed than usual, about 1,000 instead of 200 to 500.

Publisher's Mark and Motto

Manutius chose the image of a dolphin wrapped around an anchor as his publisher's mark in June 1502. This symbol is linked to the Latin phrase festina lente, which means "make haste slowly." It suggests being quick but also steady when working on a big plan. Manutius got the symbol and phrase from an old Roman coin.

Manutius's editions of classic books were so respected that other printers quickly copied his dolphin-and-anchor symbol. Many modern groups still use this image today.

Portable Books (Enchiridia)

Manutius called his new small books "libelli portatiles in formam enchiridii," meaning "portable small books in the form of a manual." The word enchiridion can also mean a handheld weapon. This suggests that Aldus wanted his portable books to be tools for scholars. He designed the italic font especially for these pocket-sized classics.

Manutius started making smaller books in 1501 with the publication of Virgil. Over time, Manutius advertised his portable books in the dedication pages he published.

Many scholars believe that creating the portable book was Manutius's most famous contribution to printing. These small books were the first simple, easy-to-carry texts. In the 15th century, books were often chained to reading stands to protect them. This meant readers had to stay in one place. Publishers also often added many notes and comments to their books. This made books very large and hard to carry. The Aldine Press changed this. Manutius's books were "published without commentary and in smaller sizes." His famous small books are often seen as the first version of the modern paperback.

These small books were not cheap, but they were reasonably priced for the time. Manutius sold his Latin books for 30 soldi, which was a fourth of a ducat. His Greek books cost twice as much, 60 soldi. For comparison, a skilled builder might earn about 50 soldi a day.

Typefaces

Everyday handwriting in Venice was in cursive (slanted and flowing). But at the time, printed books copied formal handwriting styles. Manutius asked for new typefaces that looked like the handwriting of scholars. He wanted to make reading printed books feel more natural.

Manutius hired a punchcutter named Francesco Griffo to create the new typefaces. Scholars have different ideas about whose handwriting inspired these typefaces. The Aldine Press also asked for the first Greek script where accents and letters were made separately. This typeface was first used in 1495. The Roman typeface was finished later that year.

Manutius and Griffo's original typeface is the first known example of italic type. Manutius used it until 1501. The first full book printed in italic type was Virgil's Opera in 1501. Manutius and Griffo later had a disagreement. Griffo left and gave the italic type to other publishers. Griffo's original italic type did not include capital letters, so many of the Aldine Press books did not use capital letters.

In 1502, a publication included a special permission from the Doge of Venice. This permission said that no one was allowed to copy or use Manutius's Greek and Italic typefaces. Even with this legal protection, Manutius could not stop printers outside of Venice from using his work. This made his typefaces very popular outside of Italy.

Copies and Piracy

As the Aldine Press became more popular, many fake Aldine books appeared. Manutius got special permissions for his printing press from the Venetian government. These permissions covered his typefaces, his new small book size, and even specific texts. The Pope also gave Manutius printing permissions. But these permissions did not stop people from making fake Aldine books, because there was little punishment for copying books back then.

Manutius tried to stop piracy by putting clear warnings at the end of his books. For example, in one book, he warned that "no one is allowed to print this without penalty." In 1503, Manutius tried to warn buyers about fake books. He said that books appearing under his name in Lyon were "full of errors" and "deceived unwary buyers due to the similarity of typography and format." He also said the paper was poor quality and the printing looked "French." He described the errors in detail so readers could tell a real Aldine book from a fake. But the printers in Lyon quickly used Manutius's advice to make their fake books better.

Illuminated Manuscripts and Prefaces

Before printing presses, artists created illuminated manuscripts by hand. When printing became popular, woodcuts were used to add pictures to many books. These woodcuts were often reused, which made them less special. Many of the Aldine Press's books had pictures. Manutius let his customers decide the details of the pictures while he focused on translating and publishing.

Introductions, called prefaces, were common in first editions of Latin books. Manutius used these prefaces in his Aldine editions to ask scholarly questions and give information to his readers. In one preface, he discussed which parts of a poem were written by a different poet. In another, Manutius explained how a sundial works.

Personal Life

In 1505, Manutius married Maria, the daughter of Andrea Torresani. Torresani and Manutius were already business partners. The marriage combined their shares in the publishing business. After the marriage, Manutius lived in Torresani's house. In 1506, the Aldine Press moved to a new location in Venice.

In March 1506, Manutius decided to travel for six months to find new and reliable old books. While traveling, border guards arrested him by mistake. Manutius knew the Marquis of Mantua and wrote letters to him to explain. It took six days for his imprisonment to be noticed. He was eventually released. This experience led Manutius to dedicate a new edition of Horace to the person who helped him.

Manutius wrote his will on January 16, 1515. He died the next month, on February 6. After his death, Torresani and his two sons continued the business. Eventually, Manutius's son, Paulus, took over the business. Paulus won a lawsuit to get full ownership of Manutius's italic typeface. He led the press with his brothers until his death in 1574. The publishing symbol and motto were used by the Aldine Press until the company closed down.

Manutius dreamed of creating a trilingual Bible (in three languages), but he never finished it. However, before he died, Manutius had started an edition of the Septuagint, which is the Greek Old Testament translated from Hebrew. This was the first time it was ever published, and it came out after his death in 1518.

Modern Influence

The year 1994 marked 500 years since Aldus Manutius published his first book. A scholar named Paul F. Grendler wrote that "Aldus made sure many ancient texts survived. He also greatly helped spread the ideas and knowledge of the Italian Renaissance throughout Europe." He removed extra comments from books because he felt they stopped the reader from directly connecting with the author.

Legacy

The Aldine Press published over 100 books from 1495 to 1505. Most were Greek classics, but many important Latin and Italian works were also printed.

Erasmus was very impressed by Manutius. He praised Manutius's "tireless efforts" to bring back ancient learning, calling it "a Herculean task." He also said that "Aldus is building up a library which has no other limits than the world itself."

In Bassiano, Manutius's birthplace, a monument was built to remember him 450 years after his death. The words on it are Manutius's own: "for the abundance of good books which, we hope, will finally put to flight all ignorance."

Because of the high quality and popularity of Manutius's work, his books became more expensive in the 20th century than other books from the same time.

See also

In Spanish: Aldo Manucio para niños

In Spanish: Aldo Manucio para niños