Aleksandr Popov (physicist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Popov

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Alexander Stepanovich Popov

16 March 1859 Turyinskiye Rudniki settlement, Perm Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 13 January 1906 (aged 46) St. Petersburg, Russian Empire

|

| Known for | Radio |

| Awards | Order of St. Anna of 3rd and 2nd grades Order of Saint Stanislaus (Imperial House of Romanov) of 2nd grade Silver medal of Alexander III reign honour on the belt of Order of Alexander Nevsky Prize of Imperial Russian Technical Society |

| Signature | |

Alexander Stepanovich Popov (sometimes spelled Popoff; Russian: Алекса́ндр Степа́нович Попо́в; March 16, 1859 – January 13, 1906) was a Russian physicist. He was one of the first people to invent a device that could receive radio signals.

Popov was a teacher at a Russian naval school. This work led him to study how electricity behaves at high frequencies. On May 7, 1895, he showed off a wireless lightning detector he had built. This device used a special part called a coherer to find radio noise from lightning. Today, May 7 is celebrated in Russia as Radio Day. On March 24, 1896, Popov showed that he could send radio signals 250 meters (about 820 feet). He sent these signals between different buildings in St. Petersburg. His work was similar to that of other scientists like Oliver Lodge and Guglielmo Marconi.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Alexander Popov was born in a town called Krasnoturinsk in the Urals region. His father was a priest. From a young age, Alexander was very interested in science. His father wanted him to become a priest too. So, he sent Alexander to the Seminary School in Yekaterinburg.

At the seminary, Alexander became even more interested in science and math. Instead of going on to study theology, he enrolled at Saint Petersburg State University in 1877. There, he studied physics. He graduated with honors in 1882 and stayed at the university as a lab assistant. However, the pay was not enough to support his family. So, in 1883, he took a job as a teacher and lab head at the Russian Navy's Torpedo School. This school was in Kronstadt, on Kotlin Island.

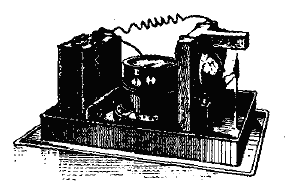

Popov's Radio Wave Receiver

While teaching at the naval school, Popov also did his own research. He was trying to solve a problem with electrical wires on steel ships. This led him to study high-frequency electrical currents. His interest in this area, including the new field of "Hertzian" or radio waves, grew after a trip in 1893. He visited the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition in the United States. There, he met and talked with other scientists working in the field.

Popov also read an article from 1894 about experiments by British physicist Oliver Lodge. Lodge's work was related to the discovery of radio waves by German physicist Heinrich Hertz six years earlier. After Hertz died, Oliver Lodge gave a talk on June 1, 1894. He showed how Hertzian waves (radio waves) could be sent up to 50 meters (about 164 feet). Lodge used a detector called a coherer. This was a glass tube with metal filings inside. When radio waves hit the coherer, it became conductive. This allowed electricity from a battery to flow through it. The signal was then picked up by a device called a mirror galvanometer. After receiving a signal, the metal filings in the coherer had to be reset. This was done by hand or by a bell that rang nearby.

Popov decided to design a more sensitive radio wave receiver. He wanted to use it as a lightning detector. This device would warn of thunderstorms by finding the electromagnetic pulses from lightning strikes. It would use a coherer receiver.

How the Lightning Detector Worked

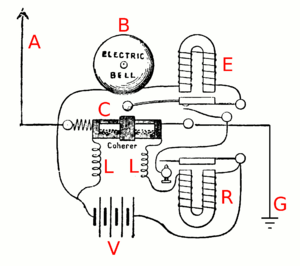

In Popov's lightning detector, the coherer (marked C) was connected to an antenna (A). It was also connected to another circuit with a relay (R) and a battery (V). This circuit operated an electric bell (B). When radio noise from a lightning strike hit the coherer, it turned on. Then, electricity from the battery flowed to the relay. The relay closed its contacts, sending current to the electromagnet (E) of the bell. This made the bell arm move and ring the bell.

Popov added a clever feature: an automatic reset. The bell arm would spring back and tap the coherer. This would reset it, making it ready to receive the next signal. Two chokes (L) in the coherer's wires stopped the radio signal from short-circuiting through the DC circuit. Popov connected his receiver to a wire antenna (A) placed high in the air and to the ground (G). This antenna idea might have come from lightning rods. It was an early use of a single wire antenna.

Early Demonstrations and Communication

On May 7, 1895, Popov gave a presentation called "On the Relation of Metallic Powders to Electric Oscillations". In this talk, he described his lightning detector. Most sources from Eastern countries consider Popov's lightning detector to be the first radio receiver. That's why May 7 has been celebrated as "Radio Day" in Russia since 1945. However, there is no clear proof that Popov sent any messages during this first demonstration.

The first time Popov showed communication using radio waves was on March 24, 1896. He demonstrated this at the Physical and Chemical Society. Some reports say that the Morse code message "ГЕНРИХ ГЕРЦ" ("HEINRICH HERTZ" in Russian) was received. The signal came from a transmitter 250 meters (about 820 feet) away. The message was then written on a blackboard by the Society president.

In 1895, Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi also began working on a wireless telegraphy system. He used "Hertzian" (radio) waves. Marconi developed a spark-gap transmitter and a much better coherer receiver that reset automatically. By mid-1895, Marconi had sent messages half a mile (800 meters). He then had the idea to ground both his transmitter and receiver. By mid-1896, he was sending radio messages a mile and a half (2400 meters). It seems that Popov and Marconi worked on their early systems without knowing about each other's progress. However, after reading about Marconi's patent in June 1896, Popov started to develop his own long-range wireless telegraphy system.

Popov's paper about his experiments was published on December 15, 1895. He did not apply for a patent for his invention. In July 1895, he put his receiver on the roof of the Institute of Forestry building in St. Petersburg. He was able to detect thunderstorms up to 50 kilometers (31 miles) away. He also understood that his device could be used for communication. His paper, presented on May 7, 1895, ended with this thought:

I can express my hope that my apparatus will be applied for signaling at great distances by electric vibrations of high frequency, as soon as there will be invented a more powerful generator of such vibrations.

In 1896, an article about Popov's invention was reprinted. In March 1896, he successfully sent radio waves between different buildings in St. Petersburg. In November 1897, a French businessman named Eugene Ducretet built a transmitter and receiver based on wireless telegraphy. Ducretet said he used Popov's lightning detector as a model. By 1898, Ducretet was making wireless telegraphy equipment based on Popov's instructions. At the same time, Popov achieved ship-to-shore communication over 6 miles (9.7 km) in 1898 and 30 miles (48 km) in 1899.

Later Work and Achievements

In 1900, a radio station was set up under Popov's guidance on Hogland island. This station provided two-way communication by wireless telegraphy. It connected the Russian naval base with the crew of the battleship General-Admiral Apraksin. The battleship had run aground on Hogland island in November 1899. The crew was not in immediate danger, but the water in the Gulf of Finland began to freeze.

Because of bad weather and slow paperwork, the crew of the Apraksin did not arrive until January 1900 to set up the wireless station on Hogland Island. But by February 5, messages were being received reliably. The wireless messages were sent to Hogland Island from a station about 25 miles (40 km) away in Kymi (nowadays Kotka) on the Finnish coast. Kotka was chosen because it was the closest point to Hogland Island that had telegraph wires connected to the Russian naval headquarters.

By the time the Apraksin was freed from the rocks by the icebreaker Yermak in late April, the Hogland Island wireless station had handled 440 official telegraph messages. Besides helping to rescue the Apraksin's crew, more than 50 Finnish fishermen were also saved. They were stuck on a piece of drift ice in the Gulf of Finland. They were rescued by the icebreaker Yermak after distress telegrams were sent by wireless telegraphy.

In 1901, Alexander Popov became a professor at the Electrotechnical Institute. In 1905, he was chosen to be the director of the institute.

Death

In 1905, Alexander Popov became very ill. He died from a brain hemorrhage on January 13, 1906.

Honors and Legacy

Radio Day

In 1945, on the 50th anniversary of Popov's experiment, the old Soviet Union created a new holiday called Radio Day. They claimed this was the day Popov invented radio. Historians note that this holiday might have been created more for political reasons during the Cold War than for historical evidence. Radio Day is still officially celebrated in Russia and Bulgaria.

Named After Him

- A minor planet, 3074 Popov, discovered in 1979, is named after him.

- At ITU Telecom World 2011, a conference room at the ITU's headquarters in Geneva was named the "Alexander Stepanovich Popov" conference room.

Monuments

Many monuments have been built to honor Alexander Popov:

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Nizhny Novgorod, Museum of Radiophysics

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Yekaterinburg, Popov Square on Pushkin Street.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Rostov-on-Don, Radio Frequency Center of the Southern Federal District.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Krasnoturinsk

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Peterhof, Naval Institute of Radio Electronics.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Saint Petersburg, on Kamennoostrovsky Prospekt.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Moscow, Alley of Scientists, Sparrow Hills, Moscow State University.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Ryazan, at the main entrance to the Ryazan State Radio Engineering University.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Kronstadt, square at the memorial museum of the inventor of radio A. S. Popov.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Perm.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Kotka, Finland.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Dnipro, st. Stoletova.

- Monument to A. S. Popov on the territory of Odessa Electrotechnical Institute of Communications.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Dalmatovo in the territory of school No. 2.

- Monument to A. S. Popov, Omsk, the territory of “Radio Plant named after A. S. Popov", a bust.

- An obelisk, a memorial stone, and a stele on Hogland island honor the first practical radio communication session in 1900.

- A memorial stone in Kronshtadt celebrates the invention of the radio in 1895.

- A sign in Sevastopol marks 100 years of radio (1997).

Commemorative Plaques

Many plaques mark places where Popov lived, worked, or demonstrated his inventions:

- In Kronstadt, Sovetskaya St., at house 43, a plaque notes Popov gave public lectures there.

- In Kronstadt, Makarovskaya St., a plaque states Popov worked as a teacher in the former marine technical school.

- In Kronstadt, Makarovskaya St., another plaque marks the former mine officer class where Popov worked.

- In Kronstadt, 1 Makarovskaya St., a gazebo in the courtyard has a plaque stating Popov tested the world's first radio receiver there.

- In Kronshtadt, Uritsky St., on house 35, a plaque indicates Popov lived there.

- In Kronstadt, Ammerman St., on house 31, a plaque states Popov lived there.

- In Saint Petersburg, Admiralteysky passage, 2, a plaque in the Higher Naval Engineering School notes Popov taught there.

- In Saint Petersburg, Makarova Embankment, at building 22, a plaque marks where Popov lived.

- In Saint Petersburg, Professor Popov Str., on house 3, a plaque notes where Popov lived, worked, and died.

- In Saint Petersburg, Professor Popov St., 5/3, at Electrotechnical University, plaques mark where Popov lectured, his office, and where he was the first elected director.

- In Saint Petersburg, V.I., Szedovskaya line, on house 31/22, a plaque indicates Popov lived there.

- In Saint Petersburg, Pochtamtskaya St., 7, at the Central Museum of Communications, a plaque notes the museum was named after Popov.

- In Saint Petersburg, V.I., in the courtyard of Saint Petersburg State University, a plaque marks where Popov received the first radiogram.

- In Geneva, a plaque to A. S. Popov was opened at the world communications management center with support from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

Museums

Several museums are dedicated to Alexander Popov:

- Museum of Radio named after A. S. Popova, Ekaterinburg

- House-Museum of Alexander Stepanovich Popov, Krasnoturinsk

- Memorial Museum of Radio Inventor A.S. Popov, Kronstadt

- Museum-cabinet and museum-apartment of A. S. Popov, LETI, St. Petersburg

- The postal and telecommunications museum in Saint Petersburg has been named the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications since 1945.

Books and Films

- Books about A. S. Popov include "Alexander Stepanovich Popov" by Golovin G.I.

- A 1949 biographical film called Alexander Popov (film) tells the story of his life and work.

Holidays and Coins

- March 16 is Alexander Popov's birthday.

- May 7 is Radio Day.

- In 1984, the USSR State Bank issued a special 1-ruble coin dedicated to A.S. Popov.

See Also

In Spanish: Aleksandr Stepánovich Popov para niños

In Spanish: Aleksandr Stepánovich Popov para niños

- All-Russia Exhibition 1896

- Invention of radio

- Radio Day

Images for kids

-

100 years sign of radio in Sevastopol

-

Monument to Popov in Yekaterinburg city