Allan Octavian Hume facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Allan Octavian Hume

|

|

|---|---|

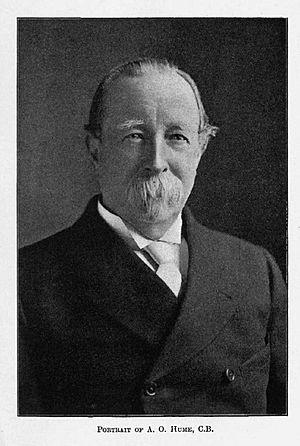

Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912)

(scanned from a Woodburytype) |

|

| Founder of Indian National Congress | |

| In office 1885–1887 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 June 1829 London, England |

| Died | 31 July 1912 (aged 83) London, England |

| Spouse |

Mary Anne Grindall (m. 1853)

|

| Children | Maria Jane "Minnie" Burnley |

| Parents | Joseph Hume (father) Maria Burnley (mother) |

| Alma mater | University College Hospital East India Company College |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Founding of Indian National Congress Father of Indian Ornithology Founding the South London Botanical Institute |

| Signature | |

Allan Octavian Hume (born June 4, 1829 – died July 31, 1912) was a British man who worked in British India. He was a political reformer, a scientist who studied birds (an ornithologist), a government worker, and a plant expert (a botanist).

Hume believed that Indians should govern themselves. He is famous for founding the Indian National Congress, a major political group in India. He was also a well-known ornithologist and is often called "the Father of Indian Ornithology."

As a government administrator in Etawah, Hume saw the Indian Rebellion of 1857 as a result of poor governance. He worked hard to make life better for ordinary people. Etawah was one of the first areas to become peaceful again. Hume's changes helped the district become a model for development. He rose in the ranks of the Indian Civil Service. However, he was brave and spoke out against British policies in India. This led to him being removed from a high position in 1879.

He started a journal called Stray Feathers where he and others wrote about birds from all over India. He built a huge collection of bird specimens at his home in Shimla. He went on trips to collect birds and also got specimens from friends.

After losing many of his important writings about birds, he stopped studying them. He gave his large collection to the Natural History Museum in London. This collection is still the biggest group of Indian bird skins there. Hume also became interested in theosophy for a short time. He left India in 1894 and moved to London. He continued to care about the Indian National Congress. Later in his life, he also became interested in botany and started the South London Botanical Institute.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Hume was born in London, England. He was one of nine children of Joseph Hume, a Scottish politician. He was taught at home until he was eleven. He later studied medicine and surgery at University College Hospital. After that, he joined the Indian Civil Services and studied at the East India Company College, Haileybury. Some of his early friends and influences included John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer.

Civil Service in India

Working in Etawah (1849–1867)

Hume arrived in India in 1849. The next year, he started working for the Bengal Civil Service in Etawah, which is now in Uttar Pradesh. He worked as a district officer from 1849 to 1867. He married Mary Anne Grindall in 1853.

Nine years after he arrived, the Indian Rebellion of 1857 broke out. Hume was involved in some military actions during this time. He was even given an award, the Companion of the Bath, in 1860. At first, he seemed safe in Etawah, but he later had to hide in Agra fort for six months. However, almost all the Indian officials stayed loyal to him. Hume returned to Etawah in January 1858. He formed a group of 650 loyal Indian soldiers and fought with them.

Hume believed the British government's mistakes caused the rebellion. He chose to be kind and forgiving when dealing with captured rebels. Only seven people were executed under his orders. The Etawah district became peaceful again within a year, which was faster than most other places.

After 1857, Hume started many reforms. As a District Officer, he introduced free primary education and held public meetings to get support for it. He also changed how the police worked and separated their law enforcement duties from their judging duties. He noticed there were not many educational books, so he started a Hindi newspaper called Lokmitra (The People's Friend) in 1859. He also managed an Urdu journal.

He strongly supported education and created scholarships for higher studies. He wrote in 1859 that education was key to preventing future revolts. He believed that a good government needed educated people who could understand its benefits.

In 1863, he pushed for separate schools for young lawbreakers instead of harsh punishments like flogging or imprisonment. He thought these punishments turned them into worse criminals. His efforts led to a special reform school near Etawah. He also started free schools in Etawah. By 1857, he had set up 181 schools with 5,186 students, including two for girls. The high school he helped build with his own money is still open today.

Hume disliked earning money from alcohol sales, calling it "The wages of sin." He supported women's education and was against forced widowhood. In Etawah, he designed a neat commercial area now called Humeganj.

Government Secretary (1871–1879)

In 1867, Hume became the Commissioner of Customs. In 1870, he joined the central government as Director-General of Agriculture. His work in reducing the costs of the customs department, which controlled salt movement along a 2,500-mile line, led to his promotion. In 1871, he became Secretary of the Department of Revenue and Agriculture.

Hume was very interested in improving farming. He felt that the government focused too much on collecting taxes and not enough on making agriculture better. He found a supporter in Lord Mayo, the Viceroy, who agreed with the idea of a dedicated agriculture department. Hume made many suggestions for improving farming, using carefully collected information.

Lord Mayo supported his ideas, and a new department was created: the Department of Revenue, Agriculture and Commerce. Hume became its Secretary in July 1871 and moved to Shimla.

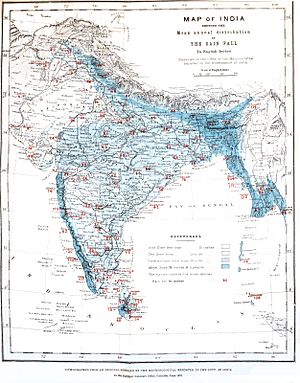

After Lord Mayo was killed in 1872, Hume lost some support for his work. However, he continued to reform the agriculture department. He improved the collection of weather data, leading to the creation of the Indian Meteorological Department in 1875. He also streamlined statistics on farming and crop yields.

Hume suggested setting up experimental farms in every district to show farmers the best ways to grow crops. He also proposed planting trees in dry areas to provide fuel. This would allow animal waste, which was often used as fuel, to be used as fertilizer instead. He believed this would help the land. He also wanted government-run banks to help farmers.

Hume was very outspoken and often criticized the government when he thought they were wrong. In 1861, he spoke against harsh punishments. He was allowed to return to his post only after apologizing for his strong criticism. He also criticized Lord Lytton's government before 1879, saying it didn't care enough about the Indian people.

Hume believed Lord Lytton's foreign policy wasted "millions and millions of Indian money." He also criticized the land tax policy, saying it caused poverty in India. His bosses were annoyed and tried to limit his power. This led him to publish a book called Agricultural Reform in India in 1879.

In 1879, Lord Lytton's government removed Hume from his high position. No clear reason was given, only that it was "in the interests of the public service." Newspapers said he was removed for being too honest and independent. The Pioneer newspaper called it "the grossest jobbery ever perpetrated." Demoted, Hume left Shimla and returned to a lower position in October 1879. He was seen as a victim because he often disagreed with government policies.

Demotion and Retirement (1879–1882)

Even after being demoted, Hume did not resign right away. Some believe he needed his salary to pay for his book, The Game Birds of India. Hume finally retired from civil service in 1882.

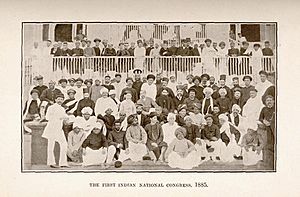

In 1883, he wrote an open letter to graduates of Calcutta University. He asked them to create their own national political movement. This led to the first meeting of the Indian National Congress in Bombay in 1885. In 1887, he famously said, "I look upon myself as a Native of India."

Return to England (1894)

Hume's wife, Mary, died in 1890. Their only daughter, Maria Jane Burnley, had married Ross Scott in Shimla in 1881.

Hume left India in 1894 and settled in London. He died at age eighty-three on July 31, 1912. His ashes were buried in Brookwood Cemetery. When news of his death reached Etawah, the market closed, and a memorial meeting was held.

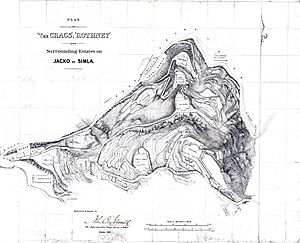

The Indian postal department released a stamp with his picture in 1973. A special cover showing Rothney Castle, his home in Shimla, was released in 2013.

Indian National Congress

Hume was known for supporting Indian people. He believed the British government had failed in India, not because they meant to, but because they didn't understand enough.

After retiring and towards the end of Lord Lytton's rule, Hume saw that people in India felt hopeless. He said the British government often ignored or even looked down on the opinions of its subjects.

There were farmer protests in the Deccan and Bombay. Hume suggested that an Indian Union could help prevent more unrest. In 1886, he wrote a pamphlet called The Old Man's Hope. In it, he discussed poverty in India and suggested that forming a representative group could help.

The idea of the Indian National Union grew. Hume initially had some support from Lord Dufferin, the Viceroy, who wanted to keep it unofficial. However, Dufferin's support didn't last long. Dufferin's successor, Lansdowne, refused to talk with Hume.

Hume took the lead, and in March 1885, a notice was sent out to hold the first Indian National Union meeting in Poona that December.

Hume tried to make the Congress bigger by including more farmers, townspeople, and Muslims between 1886 and 1887. This caused a negative reaction from the British, and the Congress had to step back. Hume was disappointed when Congress opposed raising the marriage age for Indian girls and didn't focus enough on poverty. Some Indian princes disliked the idea of democracy. Other groups tried to weaken the Congress by calling it rebellious. In 1892, Hume warned of a violent farmer revolution if leaders didn't act. This angered the British and scared Congress leaders. Disappointed by the lack of Indian leaders willing to fight for national freedom, Hume left India in 1894.

Many Anglo-Indians (British people living in India) were against the Indian National Congress. The Indian press often wrote negatively about it.

The organizers of the 27th Indian National Congress meeting in 1912 expressed their "deep sorrow" at Hume's death. They called him the "father and founder of the Congress" and thanked him for his lifelong service and sacrifice.

Contribution to Ornithology and Natural History

From his early days, Hume was very interested in science.

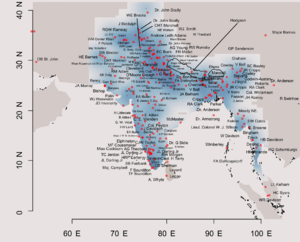

During his time in Etawah, he built a personal collection of bird specimens. However, his first collection was destroyed during the 1857 rebellion. After 1857, Hume went on several trips to collect birds. He also studied the birds of Etawah while he was a district officer there. Around 1867, he moved about 2,500 specimens to a museum in Agra. His most important work began after he moved to Shimla. He became responsible for controlling customs along a 2,500-mile line. He traveled by horse and camel, and during these trips, he observed many birds.

Hume planned to write a full book about the birds of India around 1870. His serious plan to study and record the birds of the Indian Subcontinent began when he started collecting the largest group of Asian birds at his home in Rothney Castle in Simla. He spent a lot of money on the house and gardens, turning it into a grand place with a large room for his bird museum.

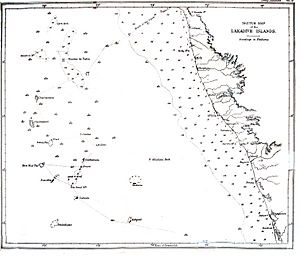

Hume went on several trips just to study birds. One big trip was to the Indus area in 1871-1872. In 1873, he visited the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. In 1875, he went to the Laccadive Islands. His last bird-watching trip was to Manipur in 1881, where he found and described the Manipur bush quail. He even spent an extra day cutting down tall grass to find specimens of this bird. He also sent a trained bird-skinner to travel with officers in places like Afghanistan to collect birds. Around 1878, he was spending about £1,500 a year on his bird studies.

Hume was a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and a Fellow of the Linnean Society. After returning to England in 1890, he also became president of a political association.

Bird Collection

Hume used his huge bird collection for his journal, Stray Feathers. He also planned to publish a complete book on Indian birds. Hume hired William Ruxton Davison to manage his bird collection. Hume trained Davison and sent him on yearly trips to collect birds across India. In 1883, Hume returned from a trip to find that a servant had stolen many pages of his writings and sold them as waste paper. This, along with damage to his museum from heavy rains, made Hume lose interest in ornithology.

He decided to donate his collection to the British Museum. He had some conditions, including that Dr. Richard Bowdler Sharpe should personally pack the collection. In 1885, after about 20,000 specimens were destroyed, Dr. Sharpe visited Hume's museum in Shimla to oversee the packing.

The Hume collection of birds was packed into 47 large wooden cases. Each case weighed about half a ton. They were transported down the hill by bullock cart to Kalka and then to the port in Bombay. The collection that went to the British Museum in 1885 included 82,000 specimens. Of these, 75,577 were placed in the museum, including 258 type specimens (original examples of a species). Hume had destroyed 20,000 specimens earlier because they were damaged by beetles. He also donated 223 hunting trophies and 371 mammal skins.

The Hume Collection included 258 type specimens. It also had nearly 400 mammal specimens, including new species like the Manipur bush rat (Hadromys humei).

His egg collection was very important because it came from reliable sources. Eugene W. Oates noted in 1901 that the collection was made of specimens with known origins, unlike many other collections.

Hume and his collector Davison also collected plants. Specimens from the Lakshadweep expedition in 1875 were studied by other botanists. Hume's plant specimens were given to the Botanical Survey of India in Calcutta.

Species He Described

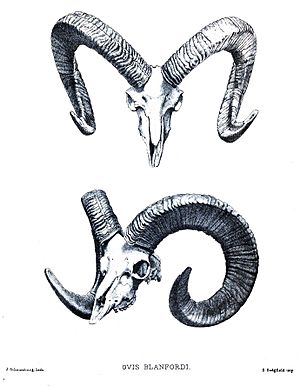

Hume described many new species of birds. Some of these are now considered subspecies (variations within a species). He also described a type of goat called Ovis blanfordi in 1877, which is now seen as a variation of the urial (a wild sheep). Hume believed that small but constant differences defined species. He understood the idea of how species change over time, but he still believed in a Creator.

Many bird species and subspecies were named by Hume. For example, he named the Manipur bush quail and the Himalayan buzzard.

One bird, the large-billed reed-warbler (Acrocephalus orinus), was known from only one specimen he collected in 1869. Its status was debated until DNA comparisons in 2002 confirmed it was a valid species. It was seen in the wild in Thailand in 2006. Later, other specimens were found in museums, and its breeding area was located in Tajikistan in 2011.

Stray Feathers Journal

Hume started his quarterly journal Stray Feathers in 1872. At that time, the only journal for Indian birds was the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Hume had only published two letters there. Other papers he sent to the Ibis journal were not published.

The President of the Asiatic Society of Bengal welcomed Stray Feathers, saying it would be a useful record of Hume's bird collection and a way to quickly publish new discoveries. Hume used the journal to describe his new findings. He wrote a lot about his own observations and also reviewed other bird books. This earned him the nickname "Pope of Indian ornithology." He criticized some naturalists for changing bird names just to claim authority without actually discovering them.

Hume was sometimes criticized in return, but he also made friends. For example, he named a species, Psittacula finschii, after Friedrich Hermann Otto Finsch.

Hume understood how geology and weather could affect bird distribution. He included an article on bird bones and classification in his journal. He also saw the value of weather data for studying where birds live. He noted how areas with high rainfall had birds similar to those found in Malaysia.

Sometimes, Hume included his personal beliefs in Stray Feathers. For example, he believed that vultures could fly by changing their body's "polarity" to repel gravity. He even claimed that some Indian Yogis could do this.

Network of Correspondents

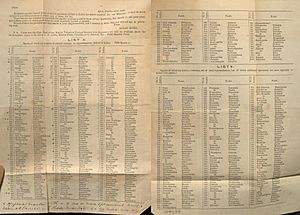

Hume communicated with many bird experts and hunters who helped him by sending reports from different parts of India. More than 200 people are listed in his Game Birds book alone. This large network allowed Hume to cover a much wider area in his bird studies.

During Hume's time, Edward Blyth was considered the father of Indian ornithology. However, Hume's work, using his large network, was also highly praised. James Murray said Hume was the top authority on Indian birds and that all future work would build on his.

Many of Hume's correspondents were important naturalists and sportsmen stationed in India.

Hume also exchanged bird skins with other collectors. He kept up to date with the work of ornithologists outside India. He helped George Ernest Shelley with specimens for his book on sunbirds.

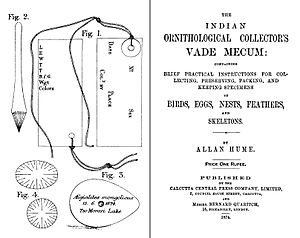

Collector's Vade Mecum (1874)

Hume's huge collection from across India was possible because he worked with many people. He made sure these helpers took accurate notes and prepared specimens carefully. He published The Indian Ornithological Collector's Vade Mecum to give advice to potential collaborators. This book explained how to prepare bird specimens, make glues, and keep records. It also covered how to use local people to catch birds and get eggs.

Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon (1879–1881)

This three-volume book on game birds was co-written by Hume and C. H. T. Marshall. It used notes from over 200 correspondents. Hume sent specific instructions to the artists for the bird illustrations. He was not happy with many of the pictures and added notes about them in the book. Hume started this book when the government demoted him. He needed the money from its publication, which cost about £4,000, to continue. He retired from service in 1882 after the book was published.

Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds (1883)

This was another important book by Hume. It described the nests, eggs, and breeding seasons of most Indian bird species. It used notes from his journal contributors and other sources. Hume also made interesting observations, like how caged female birds could still lay fertile eggs even without males.

A second edition of this book was published in 1889, edited by Eugene William Oates. This was after Hume had lost interest in ornithology due to the theft of his writings.

This event almost ended Hume's interest in birds. His last writing on ornithology was an introduction to a book about Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka's scientific work in 1891. Stoliczka had asked Hume to edit the bird section before he died.

Birds Named After Hume

Several birds are named after Allan Octavian Hume, including:

- Hume's ground tit, Pseudopodoces humilis

- Hume's wheatear, Oenanthe albonigra

- Hume's leaf warbler, Phylloscopus humei

Other animals named after him include the Manipur bush rat, Hadromys humei.

Theosophy

Hume became interested in theosophy around 1879. Theosophy is a spiritual movement that combines ideas from different religions and philosophies. Hume didn't have much respect for traditional Christianity, but he believed in the soul living forever and in a supreme being. He wanted to become a student of Tibetan spiritual teachers. During his time with the Theosophical Society, Hume wrote three articles called Fragments of Occult Truth.

Madame Blavatsky, a founder of the Theosophical Society, often visited Hume's home in Shimla.

Hume soon became unhappy with the Theosophists and lost all interest in the movement by 1883.

Hume's interest in theosophy connected him with many independent Indian thinkers, like Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who also had nationalist ideas. This connection helped lead to the idea of creating the Indian National Congress.

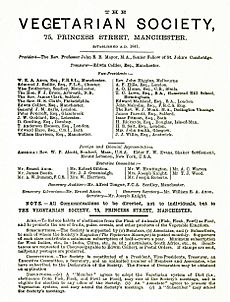

Because of his involvement in theosophy, Hume became a vegetarian and stopped killing birds for his collections.

South London Botanical Institute

After losing his bird notes, Hume stopped studying birds and became very interested in gardening at his home in Shimla.

Hume became interested in wild plants, especially invasive species. He didn't publish much about plants, only three short notes between 1901 and 1902. In 1901, Hume asked W.H. Griffin to help him create a collection of plant specimens (a herbarium). Hume would arrange his plants artistically on sheets before pressing them. They went on many plant-collecting trips together. In 1910, Hume bought a building and turned it into a herbarium and library. He called it the South London Botanical Institute (SLBI). Its goal was to encourage the study of botany in South London.

One of the institute's aims was to promote botany as a way to improve the mind and relax. Hume didn't want any public ceremony to open the institute. The first curator was W.H. Griffin, and Hume gave the institute £10,000. Frederick Townsend, a famous botanist who died in 1905, left his plant collection to the institute. Hume left £15,000 in his will for the institute's upkeep.

Before starting the institute, Hume connected with many leading botanists. He worked with Frederick Hamilton Davey on the Flora of Cornwall (1909), a book about plants in Cornwall. Hume helped with the book and paid for its publication. The SLBI now has a collection of about 100,000 plant specimens, mostly flowering plants from Europe, including many collected by Hume.

Works

- My Scrap Book: Or Rough Notes on Indian Oology and Ornithology (1869)

- List of the Birds of India (1879)

- The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds (3-volumes)

- with Marshall, Charles Henry Tilson (1879). The Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. Calcutta: A.O. Hume & C.H.T. Marshall. OCLC 5111667. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/64912. (3-volumes, 1879–1881)

- Hints on Esoteric Theosophy

- Agricultural Reform in India (1879)

- Lahore to Yarkand. Incidents of the Route and Natural History of the Countries Traversed by the Expedition of 1870 under T. D. Forsyth

- Stray Feathers (11-volumes + index by Charles Chubb)

See also

In Spanish: Allan Octavian Hume para niños

In Spanish: Allan Octavian Hume para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |