Art Tatum facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Art Tatum

|

|

|---|---|

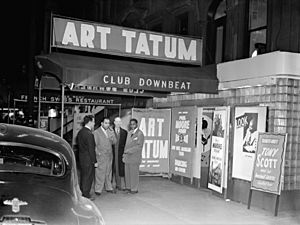

Tatum in 1946–1948 by William P. Gottlieb

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Arthur Tatum Jr. |

| Born | October 13, 1909 Toledo, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 5, 1956 (aged 47) Los Angeles, California |

| Genres | Jazz, stride |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Years active | Mid-1920s–1956 |

| Labels | Brunswick, Decca, Capitol, Clef, Verve |

Arthur Tatum Jr. (October 13, 1909 – November 5, 1956) was an American jazz pianist. Many people consider him one of the greatest jazz pianists ever. From early in his career, other musicians praised his amazing technical skill. Tatum also expanded what jazz piano could do. He used new ways of changing chords (reharmonization), arranging notes (voicing), and even playing in two keys at once (bitonality).

Tatum grew up in Toledo, Ohio. He started playing piano professionally as a teenager. He even had his own radio show that was heard across the country. In 1932, he left Toledo. He then played solo piano at clubs in big cities like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. For most of his career, he would play paid shows. Then, he would often play for hours after the clubs closed.

In the 1940s, Tatum led a successful music trio for a short time. He also began playing in more formal jazz concerts. These included events produced by Norman Granz called Jazz at the Philharmonic. His popularity went down later in the 1940s. This was because he kept playing in his own style, even as a new style called bebop became popular. In the mid-1950s, Norman Granz recorded Tatum a lot. He recorded him playing solo and with small groups. The last recording session was just two months before Tatum passed away. He was 47 years old.

Contents

Early Life and Music Beginnings

Tatum's mother, Mildred Hoskins, was a domestic worker. His father, Arthur Tatum Sr., was a mechanic. They moved from North Carolina to Toledo, Ohio, in 1909. Art was born in Toledo on October 13, 1909. He was the oldest of their four children to survive. His family was seen as traditional and went to church.

From when he was a baby, Tatum had trouble seeing. He had several eye operations. By age 11, he could see things close up and maybe tell colors apart. However, he was attacked in his early twenties. This attack caused him to become completely blind in his left eye. He had very limited vision in his right eye. Even so, he enjoyed playing cards and pool.

It is not clear if Tatum's parents played music. But he probably heard church music when he was young. He started playing the piano at a young age. He played by ear, meaning he could play just by listening. He also had an excellent memory and could tell the exact pitch of notes (perfect pitch). As a child, he was sensitive to how the piano sounded. He insisted it be tuned often. He learned songs from the radio, records, and by copying piano roll recordings. He loved sports his whole life. He had an amazing memory for baseball statistics.

Tatum first went to Jefferson School in Toledo. Then he moved to the School for the Blind in Columbus, Ohio, in late 1924. After less than a year, he went to the Toledo School of Music. His formal piano teacher, Overton G. Rainey, was also visually impaired. He taught classical music and did not like jazz. So, it is likely that Tatum mostly taught himself how to play jazz piano. By the time he was a teenager, Tatum was playing at social events. He was probably paid to play in Toledo clubs around 1924–25.

Growing up, Tatum was inspired by Fats Waller and James P. Johnson. They were known for the stride piano style. He was also influenced by Earl Hines, who was a bit older. Tatum said Waller was his biggest influence. Other musicians said Hines was one of his favorite jazz pianists. Another influence was Lee Sims, who played classical music. Sims used special chord sounds and a full, orchestral style that Tatum later used.

Career Highlights and Later Life

Early Career in the 1930s

In 1927, Tatum won a competition. He then started playing on Toledo radio station WSPD. He soon had his own daily show. After playing at clubs, Tatum often went to after-hours clubs. He enjoyed listening to other pianists. He preferred to play after everyone else had finished. He often played for hours until dawn. His radio show was at noon, which gave him time to rest. From 1928–29, his radio show was heard nationwide. Tatum also began playing in bigger cities like Cleveland and Detroit.

As Tatum's fame grew, famous musicians like Duke Ellington visited clubs where he played. They were very impressed. His biographer said that Tatum's playing was "of a different order from what most people, from what even musicians, had ever heard." It made musicians rethink what was possible. Tatum was encouraged, but he felt he was not ready to move to New York City. New York was the center of the jazz world.

This changed in 1932. Singer Adelaide Hall heard Tatum play in Toledo. She hired him to join her band in New York. On August 5, 1932, Tatum made his first studio recordings with Hall. He also recorded a solo piano test of "Tea for Two" that was not released for many years.

After arriving in New York, Tatum took part in a "cutting contest" in Harlem. This was a musical battle with famous stride piano masters. Tatum played his versions of "Tea for Two" and "Tiger Rag". James P. Johnson later said, "When Tatum played 'Tea for Two' that night I guess that was the first time I ever heard it really played." Tatum quickly became the top jazz piano player. He and Waller became good friends.

Tatum's first solo piano job in New York was at the Onyx Club. This club was one of the first jazz clubs on 52nd Street. This street became a famous place for jazz. In March 1933, he recorded his first four solo songs for Brunswick Records. "Tiger Rag" became a small hit. People were amazed by its fast speed and Tatum's technical skill.

During the tough economic times of 1934 and 1935, Tatum mostly played in Cleveland. He also recorded in New York and performed on national radio. In August 1935, he married Ruby Arnold. The next month, he started playing for about a year at the Three Deuces in Chicago.

Tatum later moved to California. He traveled by train because he was afraid of flying. There, he continued his pattern of paid shows followed by long after-hours playing. He also played for Hollywood parties and on Bing Crosby's radio show. In 1937, he recorded for the first time in Los Angeles. He then traveled between Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York, playing in major jazz clubs.

Success and Concerts in the 1940s

In March 1938, Tatum traveled to England. He performed there for three months. He liked the quiet audiences who listened carefully. He also appeared on BBC Television. His trip overseas seemed to boost his reputation. He then had longer stays at clubs in New York. Sometimes, clubs would not serve food or drinks while he was playing.

Tatum recorded many songs in 1938 and 1939. However, most were not released for a long time. This might be because big band music was becoming more popular. One of his released songs, "Tea for Two," was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1986. A recording from 1941, "Wee Baby Blues," was very successful. It sold about 500,000 copies. Informal recordings of Tatum from 1940 and 1941 were released later as the album God Is in the House. He won a Grammy Award for it after he passed away. The album's title came from Fats Waller's reaction when Tatum entered a club: "I only play the piano, but tonight God is in the house."

Tatum earned a good living from his club performances. In 1943, he could make at least $300 a week as a solo artist. When he formed a trio later that year, they were advertised at $750 a week. The trio included guitarist Tiny Grimes and bassist Slam Stewart. They were very popular on 52nd Street. They attracted more customers than almost anyone else. They also appeared briefly in a film. While critics loved Tatum as a solo pianist, the trio brought him more popular success. Tatum won Esquire magazine's prize for pianists in 1944. This led to him playing at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

All of Tatum's studio recordings in 1944 were with his trio. He stopped playing with the trio in 1944. In early 1945, Billboard magazine reported that Tatum was paid $1,150 a week as a soloist. This was a very high amount for the time.

Tatum began playing in more formal jazz concerts from 1944. He played in concert halls at towns and universities across the United States. These venues were much larger than jazz clubs. This allowed Tatum to earn more money for less work. He preferred not to have a set list of songs for these concerts. He recorded with the Barney Bigard Sextet and nine solo songs in 1945.

Tatum faced health challenges, which were common among jazz musicians at the time. These challenges did not seem to affect his playing.

Concert performances continued in the late 1940s. He played at Norman Granz-produced Jazz at the Philharmonic events. In 1947, Tatum appeared in the film The Fabulous Dorseys. A 1949 concert in Los Angeles was recorded and released. In the same year, he signed with Capitol Records. He also played at Club Alamo in Detroit. He stopped playing there when a black friend was not served. The owner then advertised that black customers were welcome. Tatum then played there often.

Even though Tatum was admired, his popularity decreased in the mid-to-late 1940s. This was likely because of the rise of bebop, a music style Tatum did not adopt.

Final Years and Legacy (1950–1956)

Tatum started working with a trio again in 1951. This trio recorded in 1952. In the same year, Tatum toured the United States with other pianists. These concerts were called "Piano Parade."

Tatum had not recorded solo for four years. But then, Norman Granz decided to record him extensively. Granz, who owned Clef Records, let Tatum play whatever he wanted. This was very unusual for the recording industry at the time. Starting in late 1953, Tatum recorded 124 solo songs. Most of these were released on 14 LPs. Granz said that during one song, the recording tape ran out. But Tatum just listened to the last few seconds and continued playing perfectly on the new tape. These solo songs were released as The Genius of Art Tatum. They were added to the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1978.

Granz also recorded Tatum with other famous musicians. These recordings led to 59 released songs. Critics had mixed feelings about these recordings. Some said Tatum was not playing "real jazz" or was past his best. Others praised his detailed playing and technical perfection. These releases brought new attention to Tatum. He won DownBeat magazine's critics' poll for pianists three years in a row.

Tatum's health declined in 1954. That year, his trio toured with bandleader Stan Kenton. Tatum sometimes traveled long distances by overnight train. He also appeared on television in The Spike Jones Show in April. He played "Yesterdays" on the show. Very few videos of Tatum exist, so this recording is special.

After two decades, Tatum and Ruby divorced in 1955. He married Geraldine Williamson later that year. She was not very interested in music and did not usually attend his shows.

By 1956, Tatum's health was worse. However, in August, he played for his largest audience ever. 19,000 people gathered at the Hollywood Bowl. The next month, he had his last recording session with saxophonist Ben Webster. He then played at least two concerts in October. He was too unwell to continue touring, so he returned home to Los Angeles. Musicians visited him on November 4, and other pianists played for him as he lay in bed.

Tatum passed away the next day, November 5, 1956, in Los Angeles. He was buried at Rosedale Cemetery. In 1992, his second wife moved him to Forest Lawn cemetery so she could be buried next to him. Tatum was inducted into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame in 1964. He received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989.

Personality and Habits

Tatum was very independent and generous with his time and money. He did not want to be limited by Musicians' Union rules. He avoided joining for as long as he could. He also disliked anything that drew attention to his blindness. He did not want to be led physically. He would plan his own way to the piano in clubs if he could.

People who met Tatum often said he was not arrogant or showy. They described him as a gentleman. He avoided talking about his personal life or history in interviews.

After-Hours Playing and Music Choices

People said Tatum was more creative when he played informally late at night. In professional shows, he often played songs similar to his recordings. But in after-hours sessions with friends, he would play the blues. He would improvise for long periods on the same chords. He would move even further away from the original melody of a song. Tatum sometimes sang the blues in these settings, playing piano for himself.

For after-hours performances, Tatum knew many more songs than for his professional shows. For professional shows, he mostly played American popular songs. During his career, he also played his own versions of some classical piano pieces. These included Dvořák's Humoresque and Massenet's "Élégie". He also recorded about a dozen blues songs. Over time, he added more songs to his list. By the late 1940s, most new songs were medium-speed ballads. But he also played challenging songs like "Caravan" and "Have You Met Miss Jones?"

Style and Technique

Saxophonist Benny Green said Tatum was the only jazz musician who tried to combine all jazz styles. He mastered them all and then created his own unique style. Tatum changed earlier jazz piano styles with his amazing skill. Other pianists used simple, repeated rhythms. But Tatum created "harmonic sweeps of colour" and "unpredictable and ever-changing shifts of rhythm."

Music expert Lewis Porter pointed out three things about Tatum's playing. These might be missed by a casual listener. They are the unusual sounds (dissonance) in his chords. Also, his advanced use of substitute chord progressions. And his occasional use of bitonality (playing in two keys at the same time). Tatum was one of the first jazz musicians to use such advanced harmonies. Before Tatum, jazz music mostly used simple chords. He went beyond this, influenced by composers like Debussy and Ravel. He added higher notes like elevenths and thirteenths to his chords. He also added tenths (and larger intervals) to the left-hand playing of the stride piano style.

Tatum improvised differently from modern jazz players. He did not try to create new melodies over a chord pattern. Instead, he hinted at or played the original melody. He then added new melodies (countermelodies) and phrases. This created new structures based on variations. "The harmonic lines may be altered, reworked or rhythmically rephrased for moments at a time, but they are still the base underneath Tatum's superstructures." His flexible rhythm allowed him to change the number of notes per beat. He could also move away from the main tempo for long periods without losing the beat.

Critic Martin Williams noted Tatum's subtle humor in his playing. He said Tatum might be "having us on" with quirky phrases. He invited listeners to share the joke.

Before the 1940s, Tatum's style was based on popular songs. He would often fill two melodically static bars with fast runs or arpeggios. From the 1940s, he made these runs longer. He also used a harder, more aggressive touch. He increased how often he used different chords and left-hand techniques. He also balanced the sound across the piano's high and low registers.

Critic Whitney Balliett described Tatum's overall style as "orchestral and even symphonic." He used "strange, multiplied chords" and played "two and three and four melodic levels at once." This style was too dense for the new bebop music.

Some musicians criticized Tatum's approach. Pianist Keith Jarrett felt Tatum played too many notes. In a band, Tatum often did not change his playing. He would overwhelm other musicians. Clarinetist Buddy DeFranco said playing with Tatum was "like chasing a train." Tatum himself said a band got in his way.

Tatum was calm at the piano. He did not make big, showy gestures. This made his playing even more impressive. His technique seemed effortless. Pianist Hank Jones said Tatum's hands seemed to glide horizontally across the keys. Tatum's relatively straight-fingered technique, compared to classical training, added to this visual effect.

Tatum could use his thumbs and little fingers to play melodies. At the same time, he played other things with his other fingers. Drummer Bill Douglass said Tatum could "do runs with these two fingers up here and then the other two fingers of the same hand playing something else down there." His large hands allowed him to play a left-hand trill with his thumb and forefinger. He could also use his little finger to play a note an octave lower. He could reach wide intervals like twelfths with either hand. He could play fast successions of complex chords. He could play all his chosen songs in any key.

Tatum's touch on the piano was also special. For Balliett, "No pianist has ever hit notes more beautifully." Each note was "light and complete and resonant." Even at the fastest speeds, Tatum kept these qualities. Most other pianists could not play notes at all at such speeds. Pianist Chick Corea said Tatum had a "feather-light touch."

Musicians like Billy Taylor and Gerald Wiggins said Tatum could make a bad piano sound good. Wiggins said Tatum could find and avoid any keys that were not working on a bad piano. Guitarist Les Paul said Tatum sometimes pulled up stuck keys with one hand while playing.

Influence on Music

Tatum's improvisational style expanded what was possible on jazz piano. Pianists like Adam Makowicz, Oscar Peterson, and Martial Solal adopted his virtuoso solo style. Even musicians with different styles, like Bud Powell and Herbie Hancock, learned from his recordings. Mary Lou Williams said, "Tatum taught me how to hit my notes, how to control them without using pedals."

Tatum's influence went beyond the piano. His new ideas in harmony and rhythm set new standards in jazz. He made jazz musicians more aware of different chord possibilities. This helped lay the groundwork for bebop in the 1940s. His modern chord voicing and chord substitutions were also groundbreaking.

Other musicians tried to use Tatum's piano skills on their own instruments. When he first came to New York, saxophonist Charlie Parker worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant where Tatum played. Parker often listened to him. "Perhaps the most important idea Parker learned from Tatum was that any note could be made to fit in a chord if suitably resolved." Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was also affected by Tatum's speed, harmony, and daring solos. Singer Tony Bennett used Tatum's style in his singing. He would listen to Tatum's records and try to sing like him. Saxophonist Coleman Hawkins changed his playing style after hearing Tatum in the 1920s. Hawkins's style was influenced by Tatum's use of chords. This style greatly influenced how saxophone was played in jazz. It helped make the saxophone a leading instrument in jazz.

Some musicians were negatively affected by Tatum's abilities. Many pianists tried to copy him. This sometimes stopped them from finding their own style. Others, like trumpeter Rex Stewart and pianist Oscar Peterson, felt overwhelmed. They questioned their own abilities. Some musicians, like Les Paul, stopped playing the piano and switched to another instrument after hearing Tatum.

Critical Standing

There is not much published information about Tatum's life. One full biography, Too Marvelous for Words (1994), was written by James Lester. This lack of detailed coverage might be because Tatum's life and music did not fit common jazz stories. Many jazz historians have not focused on him.

Critics have strong opinions about Tatum's art. Some praise him as incredibly inventive. Others say he was boringly repetitive and barely improvised. Gary Giddins suggested that Tatum is not as famous as other jazz stars. This might be because he did not use a simple, linear style of improvisation. Instead, he played in a way that required listeners to concentrate.

Other Forms of Recognition

In 1989, Tatum's hometown of Toledo opened the Art Tatum African American Resource Center. It has books and audio materials. It also organizes cultural programs, including festivals and concerts.

In 1993, an MIT student named Jeff Bilmes created the term "tatum". He named it after the pianist's speed. It is defined as "the smallest time interval between successive notes in a rhythmic phrase." It is also "the fastest pulse present in a piece of music."

In 2003, a historical marker was placed outside Tatum's childhood home in Toledo. In 2021, a non-profit organization received grants to restore the house. Also in Toledo, the Lucas County Arena unveiled a 27-feet-high sculpture in 2009. It is called the "Art Tatum Celebration Column."

Images for kids

-

Fats Waller was a major influence on Tatum.

-

Jazz impresario Norman Granz, who recorded Tatum extensively in 1953–1956

See also

In Spanish: Art Tatum para niños

In Spanish: Art Tatum para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |