Battle of Big Bethel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Big Bethel |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

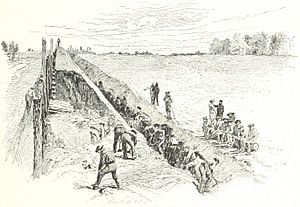

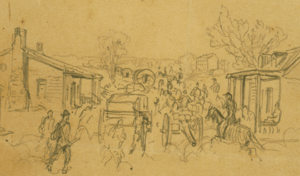

Big Bethel Alfred R. Waud, artist, June 10, 1861. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Benjamin F. Butler Ebenezer W. Peirce |

John B. Magruder Daniel H. Hill |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,500 | 1,400 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 18 killed 53 wounded 5 missing |

1 killed 9 wounded |

||||||

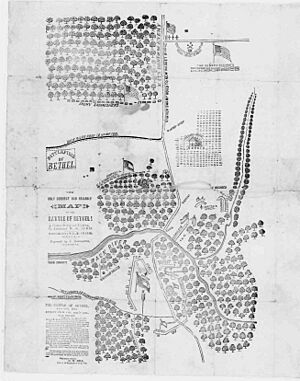

The Battle of Big Bethel was one of the first land battles of the American Civil War. It happened on June 10, 1861, near Newport News, Virginia, on the Virginia Peninsula.

After Virginia decided to leave the Union, Confederate Colonel John B. Magruder was sent to the peninsula. His job was to stop Union troops from reaching Richmond, Virginia, the new capital of the Confederacy. Union Major General Benjamin Butler commanded the Union forces at Fort Monroe. He set up new camps at nearby Hampton, Virginia and Newport News. Magruder also built two camps, at Big Bethel and Little Bethel. He hoped to trick Butler into attacking too early.

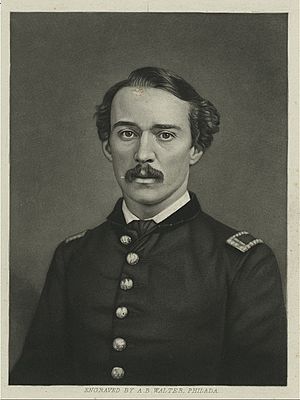

General Butler fell for the trick. He and his aide, Major Theodore Winthrop, planned a night march and a surprise attack at dawn. Butler decided not to lead the attack himself, which many criticized later. The plan was too complicated for his soldiers, who were not well trained. They also forgot to share the secret passwords. As they moved forward, a "friendly fire" incident happened. This meant Union soldiers accidentally shot at each other. This gave away their position. General Ebenezer W. Peirce, who was leading the troops, received most of the blame for the failed mission.

The Union forces had 76 casualties. This included 18 killed, 53 wounded, and 5 missing. Major Winthrop and Lieutenant John Trout Greble were among those killed. Greble was the first regular army officer to die in the war. The Confederates had only eight casualties, with one killed. After the battle, Magruder moved his forces back to Yorktown, Virginia. He built a strong defense line along the Warwick River. Even though it was a small battle, Big Bethel was seen as very important. People at the time thought the war would end quickly.

This battle was also known as the Battle of Bethel Church or Great Bethel.

Contents

Background of the Battle

Union Secures Fort Monroe

After the American Civil War started in April 1861, Virginia decided to leave the Union. It joined the Confederacy. Even before officially leaving, Virginia began taking over federal properties. However, the Union Army held Fort Monroe. This was a very strong fort at Old Point Comfort on the Virginia Peninsula. It was located between the York River and the James River. These rivers flow into Chesapeake Bay.

The fort was protected by the Union Navy. Supplies and reinforcements could reach it by water. This made it very hard for Confederate forces to attack. The fort's strong walls and many cannons also made it almost impossible to capture from land.

Colonel Justin Dimick, who commanded the fort, refused to surrender. Virginia's small, poorly equipped state forces could not take it by force. On April 20, 1861, the fort received reinforcements. Two volunteer regiments from Massachusetts arrived. These troops helped secure the fort for the Union. Fort Monroe became a key base. It helped the Union blockade Norfolk, Virginia, and the Chesapeake Bay. It also served as a starting point to retake parts of Virginia.

More volunteer regiments arrived in the following weeks. These included the 1st Vermont Infantry Regiment and several New York regiments. On May 14, 1861, Union forces took control of a well outside the fort. They also occupied the Mill Creek Bridge. This bridge was important for accessing the peninsula. Soon, Fort Monroe became too crowded. So, Union forces set up Camp Hamilton nearby. This camp was within range of the fort's guns.

General Butler Takes Charge

On May 23, 1861, Major General Benjamin Butler took command of Fort Monroe. He was a volunteer general from Massachusetts. With more troops arriving, Butler could do more than just hold the fort. He could support the Union blockade of Chesapeake Bay. He could also move up the peninsula and threaten to retake Norfolk, Virginia.

On May 27, 1861, General Butler sent troops to Newport News. This town was about 8 miles (13 km) north. It was a good spot for the Union Navy. His troops set up Camp Butler there. They also built a battery of cannons. This battery could protect the entrance to the James River. By May 29, Camp Butler was complete. It was commanded by Colonel Phelps. On June 8, the 9th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment joined the camp.

Butler also made Camp Hamilton bigger. This camp was in Hampton, Virginia, close to the fort. On June 4, 1861, General Ebenezer W. Peirce took command of Camp Hamilton.

Butler Plans to Attack Confederates

General Butler wanted to push the Confederates back. Their outposts at Little Bethel and Big Bethel were causing trouble. They were attacking Union patrols. They also blocked Butler's plan to move toward Richmond, Virginia. Richmond was the new capital of the Confederacy.

An escaped slave named George Scott helped the Union Army. He scouted the Confederate position at Big Bethel. He gave a good report to General Butler. However, Butler knew little about the Confederate position at Little Bethel. He thought it was a large, strong base.

Butler and his aide, Major Theodore Winthrop, made a plan. They would march at night. Then, they would launch a surprise attack on Little Bethel at dawn. Butler's main goal was Little Bethel. He expected to find many Confederate soldiers there. Only after taking Little Bethel would the Union commander decide to attack Big Bethel.

Opposing Forces

The Battle Begins

Union Plan and March

On the night of June 9–10, 1861, 3,500 Union soldiers began their march. They split into two groups. One group came from Camp Hamilton in Hampton. The other came from Camp Butler in Newport News. Their orders were to meet near Little Bethel. Then, they would launch a surprise attack at dawn. After taking Little Bethel, they could decide to attack Big Bethel.

Brigadier General Ebenezer W. Peirce was in charge of the entire force. He was a Massachusetts militia general. He was brave but had no formal military training or combat experience. General Butler had told Peirce the plan earlier that day. Peirce was so sick he had to travel by boat.

Peirce's orders were complex. Colonel Abram Duryée's 5th New York Infantry was to go first. They would cut the road to Big Bethel. Then, they would attack Little Bethel. Colonel Frederick Townsend's 3rd New York Infantry would follow. They would bring two howitzers for support.

Meanwhile, Colonel John W. Phelps would send troops from Newport News. These included the 1st Vermont Infantry and 4th Massachusetts Infantry. They would approach Little Bethel from the other side. Colonel Bendix's 7th New York Infantry and two artillery pieces would follow them. The plan was for these groups to meet and form a reserve force. Peirce and his staff went with Townsend's 3rd New York Infantry.

The column from Hampton started at midnight. The Newport News column started a bit later. General Butler gave specific orders to avoid confusion. All troops were to wear a white rag on their left arms. The secret watchword was "Boston." Any attacking regiment had to shout the watchword first. But Butler's messenger forgot to tell the Newport News troops about these rules.

Accidental Friendly Fire

Colonel Abram Duryée led the 5th New York Infantry. They reached Little Bethel around 4:00 a.m. They captured three Confederate guards before dawn. They were ready to attack. But then, they heard gunfire behind them.

Colonel Bendix's 7th New York Infantry had fired on Colonel Frederick Townsend's 3rd New York Infantry. Townsend's men were coming up the narrow road from Hampton. General Peirce and his staff were leading them. Bendix knew there was no Union cavalry. He thought the 3rd New York was a Confederate cavalry unit. Also, the 3rd New York wore gray uniforms. Bendix, who didn't know the watchword or armband rules, thought Confederates were behind him. He ordered his men to fire.

After Bendix's attack, Peirce pulled his troops back. They went about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to regroup. They wanted to wait for a possible Confederate attack in a better spot. Everyone was shocked to learn that Bendix had fired on his own side. Twenty-one men were wounded, and two later died. Dozens of others ran away. The colonels, including Duryea, told Peirce to stop the mission. But Butler's aides, Major Winthrop and Captain Haggerty, urged Peirce to continue. He decided to go on with the attack.

About forty men from the 3rd New York Infantry ran back to Fort Monroe. They reported that their regiment was being destroyed by a large Confederate force. Colonel William H. Allen then led the 1st New York Infantry north to help. Peirce also sent for the 2nd New York Infantry. They were ordered to stop at the New Market Bridge and act as a rear guard.

Duryée's 5th New York Infantry heard the gunfire behind them. They thought they were cut off. So, they pulled back from their advanced position. Other Union troops also moved toward the sound of the guns. The Union forces had lost the element of surprise. Their attack was also delayed.

Little Bethel Abandoned

The friendly fire incident warned the Confederates. Both the small group at Little Bethel and Magruder's main force knew the Union Army was moving. When the Union troops approached, the 50 Confederates at Little Bethel Church left their position. They fell back to their defenses near Big Bethel Church. It turned out that only a small group was at Little Bethel. General Butler had expected a much larger force.

Historians say Butler made a big mistake. The Confederates had no strong outpost at Little Bethel. So, the plan to surround it was an attack on "a man of straw." Butler could have cut the road to Yorktown. This would have forced Magruder to retreat without a fight.

The 5th New York Infantry (Duryee's Zouaves) was sent forward again. They found the Confederates fleeing Little Bethel. The 5th New York burned the church. This was to stop Confederates from using it as an outpost. They also set fire to the homes of some people who supported the Confederacy. The Union force then continued toward Big Bethel.

Confederates Return to Big Bethel

By chance, Magruder had sent many of his troops toward Hampton. He planned a surprise attack on the Union forces. But then he heard the gunfire. An elderly local lady also warned him that Union troops were close. Magruder quickly rushed his men back to their forts at Big Bethel. The Confederates were now fully aware of the Union movement. They got back into position well before Peirce's men arrived.

Almost all the Confederate troops were now behind earthworks. These were dirt walls built for defense. They were north of Marsh Creek (Brick Kiln Creek) at Big Bethel. Some of the 3rd Virginia Infantry were in an open field to the south. They were protecting a cannon meant to block the main road. These men quickly tried to dig in and find cover.

The Confederate force included Colonel D. H. Hill's 1st North Carolina Volunteer Infantry (about 800 men). There were also three companies of the 3rd Virginia Infantry (208 men). A cavalry group of about 100 men was there. And the Richmond Howitzer artillery group had about 150 men.

Union Attacks Big Bethel

Peirce decided to continue to Big Bethel. He didn't know how strong the Confederate positions were. He sent Duryee's 5th New York Infantry first. Captain Hugh Judson Kilpatrick and other scouts went ahead. They reported that the Confederates had between 3,000 and 5,000 men. They also had 30 cannons. In reality, the Confederates had about 1,400-1,500 men and 5 cannons. But Kilpatrick correctly reported that their position was very strong.

Kilpatrick also fired at Confederate scouts. This announced the Union Army's arrival at Big Bethel. As the Union force approached, they couldn't see the Confederates. The Confederates were hidden behind their defenses. But the Confederates could see the Union troops' bayonets and flag. Major Randolph, commanding the artillery, fired a shot. It hit the ground, bounced, and killed a Union soldier.

The battle began around 9:00 a.m. and lasted until 1:30 p.m. After the first shot, Bendix's men scattered into the trees for cover. The 5th New York Infantry charged the left side of the Confederate position. They tried to cross the stream and go around the Confederates. But heavy Confederate fire quickly forced them back.

Lieutenant Greble brought his three cannons forward. He and his small group of regular soldiers fired back. They fought bravely but had little effect. Peirce then placed his troops on both sides of the Hampton Road. He launched small attacks from these positions. Greble continued to fire while Peirce arranged his forces.

Union scouts went forward to check the Confederate strength. Most were quickly driven back. Two companies from the 5th New York advanced across an open field. They had little cover. An artillery shot went through a house and killed one man. Around noon, the 3rd New York Infantry moved forward. They tried to attack the Confederate position. But they could only get within 500 feet (150 m) before heavy fire forced them to lie down.

Colonel Townsend, leading the 3rd New York, feared he was being surrounded. He began to pull back. At the same time, a Confederate cannon broke. The Confederate commander, Colonel William D. Stuart, pulled his 200 men back to a hill. Stuart also feared he was being surrounded. Part of the 5th New York briefly took this position. But they couldn't hold it. Townsend had pulled back, leaving the 5th New York unsupported. They also had to retreat.

Meanwhile, Kilpatrick tried to lead part of the 5th New York around the Confederates. But they came under heavy fire. Lieutenant Colonel Gouverneur K. Warren led the men toward a shallow part of the creek. A small group guarding the crossing was outnumbered and retreated. Magruder sent Captain W. H. Werth with a cannon. Werth reached the crossing before the Union troops. He drove them off with a cannon shot. The 5th New York Infantry was tired from marching and fighting. So, they were pulled back. Kilpatrick was badly wounded and had to be carried away.

Key Deaths and End of Battle

The 5th New York Infantry was replaced for one last attack. Major Theodore Winthrop led this assault. He was an officer on General Peirce's staff. Winthrop led troops from the 5th New York, 1st Vermont, and 4th Massachusetts. They tried to go around the Confederate left side. Winthrop and his men crossed the creek without being seen. They tied white cloths around their hats. They pretended to be Confederates. Then they cheered and ran forward, giving away their identity too early.

Two companies of the 1st North Carolina Infantry turned to face them. Their fire forced the Union troops back. Major Winthrop was killed. He had jumped onto a log and yelled, "Come on boys, one charge and the day is ours." These were his last words. He was shot through the heart as his men fled back across the creek.

Union scouts continued to fire from a house and other buildings. Colonel Hill asked for volunteers to burn the house. Fire from across the road stopped them. One volunteer, Private Henry Lawson Wyatt, was killed. He was the only Confederate soldier killed in the battle. Soon, Major Randolph destroyed the house with artillery fire.

Lieutenant Greble, whose cannons had been hidden by the house, kept firing. This exposed his position. By this time, the battle was ending. Peirce ordered all his forces to retreat. It was clear the Confederate position was too strong. His troops were too tired to continue.

Lieutenant John Trout Greble refused to leave until the very end. He kept working his remaining cannon. He didn't have enough men left for both. This cost him his life. Confederate artillery focused on his position. He was hit in the back of the head by a cannonball. Greble was the first graduate of West Point and the first U.S. Regular Army officer killed in the war.

The Union troops arrived back at Fort Monroe around 5:00 p.m. They had left coats and equipment along the road. About 100 Confederate cavalry pursued them. But they couldn't attack. They pulled back when they reached Hampton. The Union force had pulled up the New Market Bridge. This stopped the Confederate pursuit.

Aftermath of the Battle

The Union Army had 76 casualties at the Battle of Big Bethel. This includes the friendly fire incident. There were 18 killed, 53 wounded, and 5 missing.

Union forces did not try to advance on the Virginia Peninsula again until 1862. However, General Butler did send a group up the Back River on June 24, 1861. With naval support, they destroyed 14 transport ships and several small boats. These boats carried supplies for the Confederates. Both sides generally held and improved their positions after the battle.

Butler soon had to send many of his men to Washington. They were needed to reinforce the Union forces after the First Battle of Bull Run. People feared for the capital's safety. Butler kept the camp at Newport News. But he had to leave the camp at Hampton because he didn't have enough men. When Magruder found this out, he burned Hampton on August 7, 1861. This was to stop it from being used to shelter runaway slaves.

Butler was criticized for the disaster at Big Bethel. People questioned his decision not to lead the attack himself. His promotion to major general was approved by only two votes in the U.S. Senate. Most of the blame fell on General Ebenezer W. Peirce. Many soldiers wrote to newspapers, criticizing Peirce's leadership. Even Butler spoke of Peirce's mistakes.

In the early part of the war, uniforms were not standard. Some Union units wore gray clothing. Gray was also being adopted by the Confederate Army. A Union officer noted that a key lesson was to get rid of gray overcoats and hats. This was to prevent Union soldiers from being shot by their own troops.

The Confederates had only one killed and seven wounded.

Major Winthrop and other Union dead were buried on the battlefield by the Confederates. Later, Magruder allowed Winthrop's brother to retrieve his body. Union officers, under a flag of truce, recovered Winthrop's body.

Major Randolph's artillery and Colonel D. H. Hill's North Carolina infantry were praised by Magruder. Within hours of the battle, Magruder moved his forces to Yorktown, Virginia. He set up a strong defense line along the Warwick River. He feared another, larger Union attack.

The Confederate newspapers made the victory seem bigger than it was. They greatly exaggerated the number of Union soldiers killed. This was common for both sides in 1861.

At the time, the battle boosted Southern confidence and morale. Along with the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run six weeks later, it gave the Confederates too much hope for a quick win. Union morale was hurt. But the Northern public and military showed they were strong and determined.

Historical Notes

First Confederate Soldier Killed

Many writers say that Private Henry L. Wyatt was the first Confederate soldier killed in combat. He was from the 1st North Carolina Volunteers. This is true for the first enlisted man killed. However, Captain John Quincy Marr was the first officer killed. He died at the Battle of Fairfax Court House (June 1861) on June 1, 1861.

Claim as First Land Battle

Big Bethel was one of the first land battles of the Civil War in Virginia. Some argue that the Battle of Philippi (1861) on June 3, 1861, was the first. Others say Big Bethel was. But the Battle of Fairfax Court House (June 1861) happened on June 1, 1861. This was two days before Philippi and nine days before Big Bethel.

Historian David J. Eicher calls Fairfax Court House and Philippi "mere skirmishes." He says Big Bethel was the first "real land battle." However, he also calls all early Civil War fights "minor skirmishes." The Baltimore riot of 1861 on April 19, 1861, could also be seen as a small battle. Several people were killed and wounded. But the Confederate side was a civilian mob, not an organized army. Compared to later large battles, all engagements before the First Battle of Bull Run were small.

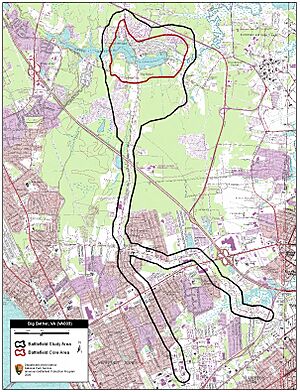

Battlefield Preservation

Most of the Big Bethel battlefield has not been saved. The entire Little Bethel site is also not preserved. Today, these areas are mostly covered by homes and businesses. Marsh Creek (Brick Kiln Creek) has been dammed. This created the Big Bethel Reservoir on the battlefield. The small parts of the site that remain are hard to recognize. The spot where Lieutenant Greble died is now a convenience store.

A group of local people is working to save parts of the battlefield. These areas are on Langley Air Force Base. They include a small part of an old earthwork. There is also a memorial to Henry Lawson Wyatt. He was the only Confederate soldier killed in the battle.