Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

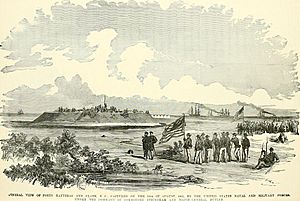

Capture of the Forts at Cape Hatteras inlet Alfred R. Waud, artist, August 28, 1861 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Silas H. Stringham Benjamin F. Butler |

Samuel Barron William F. Martin |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 9th New York Infantry 20th New York Infantry Atlantic Blockading Squadron |

17th North Carolina Infantry Regiment Hatteras Island Garrison Unspecified naval volunteers |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7 warships 935 men |

900 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed 2 wounded |

4 killed 20 wounded 691 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries happened on August 28–29, 1861. It was the first time the Union Army and Navy worked together in the American Civil War. This battle helped the Union control the important North Carolina Sounds.

The Confederates had built two forts, Fort Clark and Fort Hatteras, on the Outer Banks. These forts were meant to protect their ships that were raiding Northern trade. However, the forts were not very strong. They had few defenders and their cannons could not hit the Union ships. The Union fleet, led by Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, kept moving to avoid being an easy target. Even with bad weather, Union troops landed under General Ben Butler. They quickly took control, and Flag Officer Samuel Barron surrendered.

This battle was important because it showed how the Union Navy could block Southern ports. The Union kept both forts, which gave them a key entry point to the sounds. This greatly reduced the Confederate ship raids. The victory also cheered up people in the North after their loss at the 1st Bull Run. This fight is sometimes called the Battle of Forts Hatteras and Clark.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Why Hatteras Inlet Was Important

The North Carolina Sounds cover most of the coast from Cape Lookout (North Carolina) to the Virginia border. The Outer Banks form their eastern edge. This area was perfect for Confederate ships to hide and then attack Northern merchant ships. Cape Hatteras is the easternmost point in the Confederacy. It is close to the Gulf Stream, a fast ocean current.

Ships traveling from the Caribbean to New York or Boston would use the Gulf Stream. Confederate raiders, like privateers, could wait inside the sounds. They were safe from storms and Union blockades. When a Northern ship appeared, watchers at the Hatteras lighthouse would signal the raider. The Confederate ship would then rush out, capture the victim, and often return the same day.

Confederate Forts at Hatteras Inlet

To protect these raiders, North Carolina built forts at the inlets. Inlets are waterways that connect the sounds to the ocean. In 1861, only four inlets were deep enough for large ships: Beaufort, Ocracoke, Hatteras, and Oregon Inlets. Hatteras Inlet was the most important. So, it had two forts: Fort Hatteras and Fort Clark.

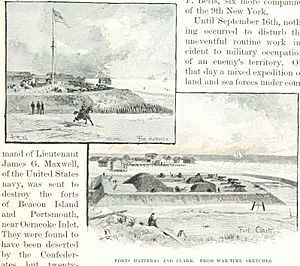

Fort Hatteras was right next to the inlet, on the sound side of Hatteras Island. Fort Clark was about half a mile (800 m) to the southeast, closer to the Atlantic Ocean. These forts were not very strong. By late August, Fort Hatteras had only ten cannons ready, with five more not set up. Fort Clark had only five cannons. Most of these cannons were light, like 32-pounders. They had a limited range and were not strong enough for coastal defense.

The forts also had too few soldiers. North Carolina had raised 22 infantry regiments for the war. But 16 of these had been sent to fight in Virginia. The remaining six regiments had to defend the entire North Carolina coast. Only a small part of one regiment, the 7th North Carolina Volunteers, was at Forts Hatteras and Clark. The other forts were also weakly held. Fewer than a thousand men guarded Forts Ocracoke, Hatteras, Clark, and Oregon. Any extra soldiers would have to come from far away, like Beaufort.

The Confederate military in North Carolina did not keep their weak defenses a secret. Several captured or shipwrecked Union captains were held loosely near Hatteras Island. They were allowed to move freely around the forts. They remembered everything they saw. When they returned North, at least two of them gave important details to the Union Navy.

Union Plans and Preparations

The attacks on Northern trade from Hatteras Inlet could not be ignored. Insurance companies pressured Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to do something. Welles already had a plan from the Blockade Strategy Board. They suggested blocking the North Carolina coast by sinking old ships in the inlets.

Secretary Welles started this plan. He ordered Commander H. S. Stellwagen to buy old ships in the Chesapeake Bay. Stellwagen also had to report to Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham. Stringham was in charge of the blockade of the North Carolina coast. This was Stringham's first involvement in the Hatteras Inlet attack. He would soon become the most important leader of the expedition.

Stringham did not like the idea of blocking the inlets. He believed that ocean currents would either wash the sunken ships away or create new channels. He thought the only way to stop the Confederates was to capture and hold the inlets. This meant the Union Navy would need help from the Army.

The Army agreed to help. This was partly because of General Benjamin F. Butler. Butler was a political leader who needed to be involved, even though he was not known for his military skills. Butler was told to gather about 800 men for the mission. He quickly had 880 soldiers. These included 500 German-speaking men from the 20th New York Volunteers. There were also 220 men from the 9th New York Volunteers. Another 100 men were from the Union Coast Guard (an Army unit). Finally, 20 regular army soldiers from the 2nd U.S. Artillery joined. The men boarded two ships, Adelaide and George Peabody. Some worried the ships could not handle a Hatteras storm. But Stellwagen said the mission could only happen in good weather anyway.

While Butler gathered his troops, Flag Officer Stringham also prepared. He learned that the War Department's orders to Butler's boss, Major General John E. Wool, said the Navy Department was in charge. Stringham decided to follow his own plan, knowing he would be blamed if things went wrong. He chose seven warships for the mission: USS Minnesota, Cumberland, Susquehanna, Wabash, Pawnee, Monticello, and Harriet Lane. All but Harriet Lane were U.S. Navy ships. Harriet Lane was a revenue cutter. He also brought the armed steam tug Fanny. This tug was needed to tow the smaller boats used for landing troops.

On August 26, the fleet, without Susquehanna and Cumberland, left Hampton Roads. They sailed down the coast towards Cape Hatteras. On the way, Cumberland joined them. On August 27, they sailed around the Cape and anchored near the inlet. The Confederate defenders could see them clearly. Colonel William F. Martin, who commanded Forts Hatteras and Clark, knew his 580 men needed help. He asked for reinforcements from Forts Ocracoke and Oregon. But communication was slow, and the first reinforcements arrived too late, the next day.

The Battle Begins

First Day: Union Attack

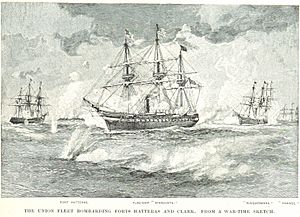

On the morning of August 28, USS Minnesota, USS Wabash, and USS Cumberland started firing at Fort Clark. The smaller warships went with the troop transports about three miles (4.8 km) east. There, the Union soldiers began to land. Stringham kept his ships moving in a circle. Wabash towed Cumberland. Around 11:00 a.m., USS Susquehanna joined the attack.

The ships would fire their cannons at the fort, then move away to reload. Then they would come back to fire again. By staying in motion, they made it hard for the Confederate gunners to aim their cannons. This made the shore-based cannons less effective against the ships. This tactic had been used before by the British and French in the Crimean War. But this was the first time the U.S. Navy used it.

The cannons from Fort Clark did not hit the Union ships. Their shots either fell short or flew over. Shortly after noon, the defenders started running out of ammunition. Around 12:25 p.m., they had no ammunition left. At this point, they left the fort. Some ran to Fort Hatteras, while others escaped in boats. Colonel Max Weber, leading the Union troops on shore, saw this. He sent some men to take over the fort. But the Union fleet did not know the fort was empty and kept firing for five more minutes. During this confusion, one Union soldier was badly wounded in the hand by a shell fragment. Luckily, some soldiers waved a large American flag. The ships saw it and stopped firing. Stringham and his captains then focused their attack on Fort Hatteras.

Meanwhile, the troop landing was difficult. Only about a third of the soldiers were ashore when strong winds caused waves to swamp the landing boats. General Butler had to stop landing more troops. Colonel Weber found he had only 318 men with him. This included 102 from his own 20th New York regiment. He also had 68 from the 9th New York, 28 from the Union Coast Guard, 45 artillerymen, 45 marines, and 28 sailors. They managed to get several field cannons ashore. With these, they could defend themselves against a Confederate counterattack. But they were too few to attack Fort Hatteras.

At Fort Hatteras, Stringham kept his ships moving. The Confederate defenders tried to save their ammunition by firing only now and then. Stringham thought the fort might be empty. (The fort's old flag was torn and had not been replaced.) He sent Monticello into the inlet to check the depth. But then the fort started firing again. The ship got stuck while trying to leave and was hit five times. None of these hits caused lasting damage, though some sailors had minor injuries.

As the day ended, the Union fleet pulled back because of bad weather. The tired Confederate defenders hoped for more soldiers. The Union troops on shore went to sleep hungry, with little water, and worried about the Confederate reinforcements.

Second Day: Confederate Surrender

Sometime after dark, Confederate reinforcements began to arrive at Fort Hatteras. The gunboat CSS Warren Winslow brought some soldiers from Fort Ocracoke. Some sailors also stayed to help man the cannons. This brought the number of men in the fort to over 700. More were expected from New Bern. Flag Officer Samuel Barron, who commanded the coast defenses of North Carolina and Virginia, arrived with the extra troops. Colonel Martin, feeling exhausted, asked Barron to take command. Barron agreed, still hoping that with more troops from New Bern, they could retake Fort Clark.

The dawn of the second day ended the defenders' hopes. The weather improved enough for the Union fleet to return and restart its bombardment. They also managed to scare away the transport ship bringing more Confederate reinforcements. (One ship did get in, but it carried away wounded soldiers instead of bringing more troops.) The Union fleet first kept moving. But they soon found they were out of range of the fort's cannons. After that, the ships stayed still. They poured fire into the fort without any danger of being hit back. The men in the forts could do nothing but endure the attack.

After about three hours, Barron held a meeting with his officers. They decided to ask for surrender terms, even though they had few casualties. (The exact numbers of dead and wounded are not perfectly known. Reports say four to seven dead, and 20 to 45 wounded.) A little after 11:00 a.m., the white flag was raised. Butler demanded a full surrender, which Barron accepted. The battle ended, and the surviving Confederates became prisoners of war. The list of prisoners had 691 names, including those who were wounded but not taken away.

After the Battle

Butler and Stringham left right after the battle. Butler went to Washington, and Stringham took the prisoners to New York. Some critics said they were trying to get all the credit for the victory. However, both men said they were trying to convince the government not to block Hatteras Inlet. With the inlet in Union hands, it was no longer useful to the Confederacy. In fact, it now allowed Union forces to chase Confederate raiders into the sounds.

Even though they and their supporters argued for weeks, it turned out to be unnecessary. The War and Navy Departments had already decided to keep the inlet. It would be used as the starting point for a large water-based attack on the North Carolina mainland early the next year. This campaign, led by Army commander Ambrose E. Burnside, completely stopped Confederate ship raids from the sounds.

The Union keeping Hatteras Inlet was also helped by the Confederates. They soon decided that the Ocracoke and Oregon forts could not be defended. So, they abandoned them.

Stringham's tactic of keeping his ships moving while attacking forts was used later by Flag Officer Samuel Francis Du Pont at Port Royal, South Carolina. This effective method made military leaders rethink how strong fixed forts were against naval cannons.

Today, no physical signs of the battle remain. However, the battlefield is protected within Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |