Bernard Lewis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bernard Lewis

|

|

|---|---|

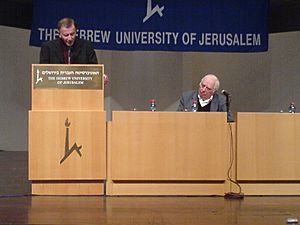

Lewis in 2012

|

|

| Born | 31 May 1916 London, England

|

| Died | 19 May 2018 (aged 101) |

| Nationality | British American |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Hélène Oppenhejm (married 1947–1974) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Fellow of the British Academy Harvey Prize Irving Kristol Award Jefferson Lecture National Humanities Medal |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | SOAS (BA, PhD) University of Paris |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Historian |

| Institutions | SOAS Princeton University Cornell University |

| Doctoral students | Feroz Ahmad |

| Main interests | Middle Eastern studies, Islamic studies |

| Notable works |

|

| Influenced | Heath W. Lowry, Fouad Ajami |

Bernard Lewis (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a famous British American historian. He was an expert in Oriental studies, which means he studied the history, cultures, and languages of the Middle East and Asia. Lewis was also known for sharing his ideas with the public and giving his thoughts on politics. He taught at Princeton University as a professor.

Lewis was especially knowledgeable about the history of Islam and how Islam and the West have interacted over time. During Second World War, he served in the British Army before working for the Foreign Office. After the war, he returned to teaching at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.

Many people saw Lewis as a top expert on the Middle East. However, some critics felt his views were too general about the Muslim world. They also thought he sometimes repeated ideas that newer research had questioned. Politically, some people said Lewis made Islam seem less advanced and focused too much on the dangers of jihad. His advice was often sought by political leaders, including the Bush administration. But his support for the Iraq War has been debated.

Lewis also had public discussions with Edward Said, another scholar. Said believed Lewis and other "Orientalists" misunderstood Islam and supported Western power. Lewis disagreed, saying that studying the Middle East was part of humanism. Lewis also had different views on the Armenian genocide. He believed the deaths during that time were due to a conflict between two groups, not a plan by the Ottoman government to wipe out the Armenian people.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Bernard Lewis was born in London, England, on 31 May 1916. His parents were Harry Lewis and Jane Levy. He became interested in languages and history when he was young, especially while preparing for his bar mitzvah. In 1947, he married Ruth Hélène Oppenhejm. They had a daughter and a son. Their marriage ended in 1974. Lewis became a citizen of the United States in 1982.

Lewis studied at the School of Oriental Studies (now School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS) at the University of London. In 1936, he earned his first degree in history, focusing on the Near and Middle East. Three years later, he received his PhD from SOAS, specializing in the history of Islam. He also studied law for a while but decided to focus on Middle Eastern history. He continued his studies in Paris, France, before returning to SOAS in 1938 as a teacher.

A Career in History

During Second World War, Lewis served in the British Army. He was part of the Royal Armoured Corps and the Intelligence Corps. After the war, he went back to SOAS and stayed there for 25 years. In 1949, when he was 33, he became a professor of Near and Middle Eastern History. He became a member of the British Academy in 1963.

In 1974, Lewis moved to the United States. He took a job at Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study. His job allowed him to teach only one semester a year. This gave him more time for research. Because of this, he wrote many books and articles during his time at Princeton. After retiring from Princeton in 1986, Lewis taught at Cornell University until 1990.

In 1966, Lewis helped start the Middle East Studies Association of North America (MESA). However, in 2007, he left MESA and started a new group called the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa (ASMEA). He felt MESA was too critical of Israel and America's role in the Middle East. ASMEA was created to promote high standards in Middle Eastern and African studies. Lewis was the chairman of its academic council.

In 1990, Lewis received the Jefferson Lecture award. This is the highest honor the U.S. government gives for achievements in the humanities. His lecture was later published as an essay called "The Roots of Muslim Rage."

Understanding the Middle East

Lewis's ideas were important not just in universities but also to the general public. He started his research by studying the medieval history of Arab countries, especially Syria. His early work on medieval Islamic guilds was considered the best for about 30 years.

After Israel was created in 1948, it became harder for Jewish scholars to do research in Arab countries. So, Lewis started studying the Ottoman Empire instead. He used Ottoman archives, which had recently become open to Western researchers. His articles changed how people understood Middle Eastern history. They showed a wide picture of Islamic society, including its government, economy, and people.

Lewis believed that the Middle East faced problems because of its own culture and religion. He thought these internal issues led to its decline. This was different from others who blamed problems on European colonization in the 1800s. In his book Muslim Discovery of Europe (1982), Lewis argued that Muslim societies did not keep up with the West. He suggested that Islamic societies began to decline as early as the 11th century. He thought this was due to internal issues like "cultural arrogance," which stopped them from learning new things.

Lewis also wrote about anti-Semitism (hatred of Jewish people) in his book Semites and Anti-Semites (1986). He argued that Arab anger towards Israel was much stronger than their anger about other problems in the Muslim world. These included the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan or the Iran–Iraq War.

Besides his academic books, Lewis wrote several popular books for everyone to read. These included The Arabs in History (1950) and The Middle East (1995). After the 11 September 2001 attacks, many people became interested in Lewis's work. His 1990 essay The Roots of Muslim Rage became very popular. After 9/11, he published three more books. What Went Wrong? explored why the Muslim world was hesitant about modern changes.

Debates and Different Views

Lewis was known for his discussions with Edward Said, a Palestinian American scholar. Said argued that Lewis's work was an example of "Orientalism." Said believed Orientalism was a way of studying the Middle East that was biased and supported Western power. He questioned if scholars like Lewis were truly neutral when studying the Arab world. Said claimed that Lewis's knowledge of the Arab world was biased and that he hadn't visited the Arab world in many years. He felt Lewis treated Islam as one single thing, ignoring its many different parts and history.

Lewis disagreed with Said. He said that Western study of the Middle East was part of a broader interest in human knowledge. He argued that this study began long before European countries had power in the Middle East. Lewis also accused Said of making the study of the Middle East too political.

Lewis's views on the Armenian genocide were also debated. In early editions of his book The Emergence of Modern Turkey, he described the events of 1915 as a "terrible holocaust" where many Armenians died. In later editions, he changed this to "terrible slaughter" and added that an unknown number of Turks also died. He argued that the deaths were the result of a struggle between two groups fighting for the same land. He stated there was no strong proof of a plan by the Ottoman government to wipe out the Armenian people.

These changes led to criticism from some historians and journalists. They suggested Lewis was changing history for political reasons. Lewis faced a court case in France for his statements, where he was ordered to pay a small amount of money. Many historians disagreed with Lewis's view, saying that while he didn't deny many people died, he denied it was a planned genocide.

His Ideas on World Events

In the mid-1960s, Lewis became a commentator on modern Middle Eastern issues. His thoughts on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the rise of militant Islam brought him public attention and some disagreement. Some historians called him a strong supporter of Israel in academic circles. His advice was highly valued by politicians. For example, U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney said Lewis's wisdom was sought daily by leaders.

Lewis was critical of the Soviet Union. He believed in a liberal approach to Islamic history. He also developed connections with governments around the world. Golda Meir, who was Prime Minister of Israel, asked her cabinet members to read Lewis's articles. During the George W. Bush presidency, Lewis advised leaders like Cheney and Bush himself. He also had ties with leaders in Jordan, Iran, Turkey, and Egypt.

Lewis believed the West should have closer ties with Israel and Turkey. He saw these countries as very important because of the Soviet Union's growing influence in the Middle East. He thought modern Turkey was special because of its efforts to become more like Western countries.

Lewis saw Christendom (Western world) and Islam as civilizations that have often been in conflict since Islam began in the 7th century. In his 1990 essay The Roots of Muslim Rage, he argued that the struggle between the West and Islam was getting stronger. This essay is sometimes credited with popularizing the phrase "clash of civilizations," which was later used by Samuel P. Huntington.

In 1998, Lewis read a newspaper article where Osama bin Laden declared war on the United States. In his essay "A License to Kill," Lewis saw bin Laden's words as the "ideology of jihad" and warned that bin Laden would be a danger to the West.

Lewis's views on the Iraq War were also significant. In 2002, he wrote an article saying that changing the government in Iraq might be risky, but not doing anything could be even riskier. Many people saw Lewis as a major intellectual influence behind the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He believed that changing the government in Iraq would help modernize the Middle East. He reportedly told Vice President Cheney that a strong response was needed after the 9/11 attacks.

However, Lewis later said that freedom and democracy cannot be forced on Islamic nations. He stated that democracy is a strong medicine that must be given in small, increasing amounts, or it could harm the patient. He believed Muslims needed to bring about these changes themselves.

Some critics, like Richard Bulliet, said that Lewis "looked down on modern Arabs." They felt he only respected them if they followed a Western path.

Views on Iran

In 2006, Lewis wrote that Iran had been working on a nuclear weapon for 15 years. He also wrote about a specific date in the Islamic calendar, 22 August 2006. He suggested this date, which was important in Islam, might be chosen by Iran for a major event, like an "apocalyptic ending of Israel." However, the day passed without any incident.

Death

Bernard Lewis passed away on 19 May 2018, at the age of 101. He died in Voorhees Township, New Jersey, just 12 days before his 102nd birthday. He is buried in Trumpeldor Cemetery in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Awards and Honors

- 1963: Became a Fellow of the British Academy

- 1973: Chosen for the American Philosophical Society

- 1978: Received the Harvey Prize for his deep understanding of Middle Eastern peoples

- 1990: Selected for the Jefferson Lecture, a top U.S. honor in the humanities

- 2002: Awarded the Atatürk International Peace Prize for his work on Turkey's history

- 2006: Received the National Humanities Medal

- 2007: Received the Irving Kristol Award

Images for kids

Error: no page names specified (help). In Spanish: Bernard Lewis para niños

In Spanish: Bernard Lewis para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |