Big Creek Hydroelectric Project facts for kids

The Big Creek Hydroelectric Project is a huge system of dams and power plants in the Sierra Nevada mountains of central California. It uses the water from the San Joaquin River and its branches, especially Big Creek, to make electricity. Because the water is used over and over again as it falls more than 6,200 feet (1,890 meters), people call it "The Hardest Working Water in the World"!

This project was built to provide electric power for the fast-growing city of Los Angeles. A smart engineer named John S. Eastwood designed the system. It was first built by Henry E. Huntington's Pacific Light and Power Company (PL&P), starting in 1911. The first electricity reached Los Angeles in 1913. Later, Southern California Edison (SCE) took over and expanded the project. Today, it has 27 dams, many tunnels, and 24 power-generating units in nine powerhouses. Together, they can produce over 1,000 megawatts of power. The six main reservoirs can hold a lot of water, which is also used for farming in the Central Valley and helps control floods. The project's facilities were recognized as important historical sites in 2016.

Every year, the Big Creek project makes almost 4 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity. This is about 90 percent of all the hydroelectric power SCE produces, and about 12 percent of all hydroelectric power made in California! The reservoirs are also popular places for fun activities like boating and fishing. However, building the project changed the environment, affecting fish and animal movement, and covering up some historical sites and traditional Native American lands.

Contents

How the Project Started

The idea for the Big Creek Project came from engineer John S. Eastwood. He explored the San Joaquin River area in the late 1880s, looking for places to build reservoirs and power plants. In 1895, he tried to develop a project on the North Fork of the San Joaquin River, but it failed because there wasn't enough money to build a dam and a drought dried up the river.

Eastwood didn't give up! He started his own company, Mammoth Power Company, planning a huge dam. But investors worried about the high costs, so he stopped that plan. Then, Eastwood came up with an even bigger idea: a system that would use the entire upper San Joaquin River basin. Instead of one giant power plant, he planned a series of smaller reservoirs and power plants, where water would generate power step-by-step as it flowed downhill. This time, he found someone willing to fund his ambitious project.

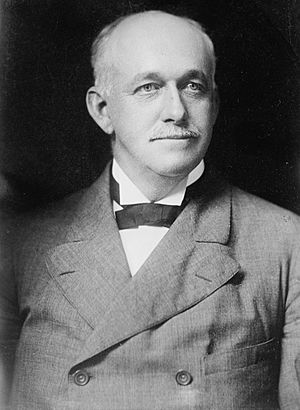

In 1902, Eastwood showed his plans to William G. Kerckhoff, a businessman connected to Henry E. Huntington. Huntington was a rich developer from Los Angeles who owned the Pacific Light and Power Company (PL&P). His company needed more electricity because Los Angeles was growing fast, and electric trains used a lot of power. Hydroelectricity was a cheaper way to make power than burning fuel. The San Joaquin River was the closest and largest river that could provide the power Huntington needed. Even though Huntington was unsure at first, he was impressed by Eastwood's studies and hired him to create a detailed plan for the project. Eastwood worked on these plans from 1902 to 1905.

PL&P quickly started claiming rights to the San Joaquin River's water. However, construction was delayed for many years. The company's leaders thought the project would make too much power for the time. By 1905, Eastwood had designed the first part of the system, with a large reservoir and two powerhouses on Big Creek. During this time, Eastwood also helped develop a new type of dam called the multiple-arch dam, which he became famous for building.

By 1907, PL&P was almost ready to build, but a financial crisis called the Panic of 1907 caused another delay. Then, in 1910, Huntington fired Eastwood. The exact reasons aren't clear, but it might have been about who controlled the project or how profits were shared. Also, investors worried about the safety of Eastwood's multiple-arch dam design and wanted to use gravity dams instead. In 1912, Eastwood lost his ownership in PL&P because he couldn't pay a fee Huntington charged to help fund the project. Even so, PL&P kept Eastwood's original plans for the Big Creek Project.

Building the Project

Getting Started and Funding

PL&P began building the Big Creek Project in February 1910. George Ward was put in charge, and the engineering firm Stone & Webster oversaw the construction. PL&P first tried to raise $10 million to pay for the project. But by October 1911, they had only sold $2.5 million worth of bonds (a way to borrow money). So, they had to sell the rest of the bonds at a lower price to a group of investment bankers.

Huntington also had to convince farmers in the San Joaquin Valley that the dams would help them, not hurt them, by providing more water. In 1906, PL&P made a deal with a big farming company, Miller & Lux. This deal allowed PL&P to build reservoirs in exchange for making sure a steady flow of water reached the farmers' lands.

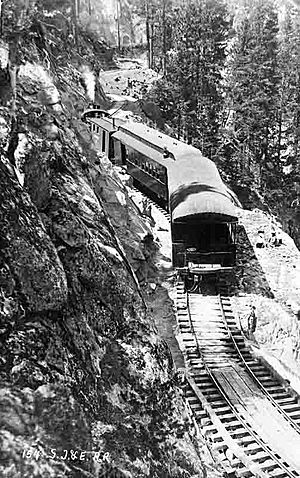

Getting workers and materials to the remote construction site was a huge challenge. Mules were too slow and expensive. So, they decided to build a railway. This railway, called the San Joaquin and Eastern Railroad, would stretch 56 miles (90 kilometers) deep into the Sierra Nevada mountains, to the company town of Big Creek.

Building the railroad started on February 5, 1912. It wound its way up the San Joaquin River Canyon, with 1,078 curves, 43 bridges, and steep slopes. People nicknamed it the "Slow, Jerky and Expensive" railroad. The last mile was especially hard to build, costing over $1 million! But it was finished in a record 157 days by July 1912. Because of its steep slopes and sharp turns, special Shay locomotives were used.

First Stage: 1913–1914

Work on the dams and powerhouses began in the summer of 1912. They started with three concrete dams (Big Creek Nos. 1, 2, and 3) to create Huntington Lake. This lake, nearly 7,000 feet (2,134 meters) above sea level, would store water to power two hydroelectric plants, Powerhouse No. 1 and No. 2, located thousands of feet below. By late summer, about 3,500 men were working across twelve camps. Construction moved very fast because they needed to start making electricity quickly to pay for the project. The budget was tight, especially since the gravity dams they chose needed much more concrete than the original multiple-arch design.

On January 7, 1913, workers went on strike to protest the difficult conditions and lack of food. PL&P fired almost 2,000 strikers and hired new workers, which caused big delays. Powerhouse No. 1 finally started making electricity on October 14, 1913. Powerhouse No. 2, further downstream, was supposed to be finished three days later, but a fire damaged it, delaying completion until December 8. This fire is thought to have been set on purpose.

In November 1913, a power plant in Los Angeles had a problem, so on November 8, the company decided to use Big Creek power for the first time. Sending electricity 240 miles (386 kilometers) was one of the longest transmissions in the world back then. The engineering challenge at Big Creek was compared to building the Panama Canal, which was also happening at the same time.

When World War I began, construction on the project paused between 1914 and 1919. In 1917, PL&P merged with Southern California Edison (SCE) as Huntington combined energy companies in Southern California.

Second Stage: 1921–1929

After the war, the economy grew, and interest in expanding the project returned. In 1919, the dams at Huntington Lake were made taller to hold more water. New plans for expansion were approved in 1921. These plans involved bringing water from other streams in the San Joaquin River system to increase the powerhouses' capacity. The first new part built was Big Creek Powerhouse No. 8, which used the last drop in elevation between Powerhouse No. 2 and where Big Creek meets the San Joaquin River.

In 1923, Dam 6 was finished on the San Joaquin River, just below where Big Creek joins it. This dam created a small reservoir for Powerhouse 8. Building this concrete arch dam was very hard because the canyon was narrow and the San Joaquin River flowed strongly. During construction, the entire river had to be carried in a special channel along the canyon wall.

Also in 1923, Powerhouse No. 3 came online. It used the combined water from Big Creek and the San Joaquin River and was called the "electrical giant of the West." It was the largest hydroelectric plant in the West, making 75 megawatts of power, which was a huge amount then. In 1923, Big Creek's power transmission system was also upgraded to 220kV, the highest commercial voltage in the world at the time. By 1925, Powerhouses Nos. 1 and 2 were expanded to handle more water from the South Fork San Joaquin River, a much larger stream east of Huntington Lake.

The South Fork diversion started bringing water on April 13, 1925, through the 13-mile (21-kilometer) Ward Tunnel. This tunnel moved water from the river into Huntington Lake. A dam was built at Jackass Meadows in 1925 to ensure a year-round water supply for this diversion. The Florence Lake Dam, built with Eastwood's multiple-arch design, was completed in 1926, forming Florence Lake. In 1927, the Mono-Bear diversions were finished, bringing water from Mono Creek and Bear Creek, two eastern branches of the South Fork. A huge siphon was built to carry water across the 700-foot (213-meter) deep South Fork valley to join the Ward Tunnel.

Even though these diversions brought much more water, the existing reservoirs couldn't hold it all. Huntington and Florence Lakes combined could hold much less water than the amount of water flowing into the San Joaquin River system each year. So, a dam was built on Stevenson Creek between 1925 and 1927, creating Shaver Lake, to store extra water from Huntington. This lake replaced an older reservoir used for a timber operation. Huntington Lake was then connected to Shaver Lake by a tunnel. Even though there was a big drop in elevation (over 1,000 feet or 305 meters) between the lakes, no power station was built there at that time.

In 1926, work began on Big Creek Powerhouse No. 2A. This powerhouse would generate power from water released from Shaver Lake. It was an extension of the Powerhouse No. 2 building and would release water into the same reservoir (Dam 5) on Big Creek. Powerhouse 2A was the last major part built during this second stage, except for an expansion to Powerhouse 8 in 1929. Most of the construction camps were taken down by the end of 1926.

More than 5,000 people worked on the project during the busiest time of the second stage. Safety rules were much stricter than in the first stage, partly because of a deadly accident in 1924 where a worker was killed. SCE also improved facilities in its company towns. Still, tough conditions meant that 40 percent of workers left each month.

The second stage expansions increased the power-generating capacity by six times, from 70 to 425 megawatts. The amount of electricity made each year grew almost eight times. By this time, Big Creek provided 70 to 90 percent of the power used in the Los Angeles area, a role it kept until the 1940s.

When the Great Depression started in the 1930s, construction stopped again. In 1933, most of the Big Creek railroad, which had carried 400,000 tons of goods in 21 years, was taken apart and sold for scrap metal. The old railroad path was then used as a road.

Third Stage: 1948–1960

After World War II ended, construction started again in 1948, beginning with an expansion of Powerhouse No. 3. In July 1949, work began on Redinger Dam, located below Powerhouse 3, and Big Creek Powerhouse No. 4. These facilities were finished by 1951, forming the lowest part of the Big Creek project. Powerhouse 4 started operating in June and July of that year.

In the 1950s, SCE added more power-generating capacity by building the project's two largest dams. First was Vermilion Valley Dam on Mono Creek in 1953. By October 1954, this huge earthen dam, over 4,200 feet (1,280 meters) long, was completed. The dam was named Lake Thomas A. Edison to honor Thomas Edison on the 75th anniversary of his invention of the lightbulb. This dam doesn't make power itself, but it stores floodwaters from Mono Creek. This water is later released into the Mono-Bear Diversion and Ward Tunnel, helping downstream power plants make more electricity during the dry season.

With new types of turbines that could work with smaller water drops, a small powerhouse was planned at the end of the Ward Tunnel in 1954. The Portal Powerhouse, built from 1954–1955, is located just above Huntington Lake. This powerhouse is special because it's not inside a building and is controlled automatically.

In early 1958, work began on Mammoth Pool Dam on the main San Joaquin River. By October 17, 1959, this 411-foot (125-meter) high rockfill dam, the tallest dam of the project, was finished. On March 28, 1960, the Mammoth Pool Powerhouse, located near Powerhouse 8, started operating.

The third stage ended with Mammoth Pool's completion. By this time, the Big Creek Project was almost fully built.

Fourth Stage: 1983–1987

The biggest powerhouse at Big Creek wasn't built until the mid-1980s. This was part of the Balsam Meadows Project. The Eastwood Powerhouse, which can generate almost 200 megawatts, was built where the tunnel from Huntington Lake meets Shaver Lake. This powerhouse is different because it's a pumped-storage operation. This means that during times when people don't need much electricity, the station pumps water from Shaver Lake up to a smaller reservoir, the Balsam Meadows Forebay, located on a nearby mountain. Then, when a lot of electricity is needed, the water is released back down to generate power. Also, this power station is located in a huge artificial cave, 1,100 feet (335 meters) deep, carved out of solid rock.

Finished in 1987, the Balsam Meadows project greatly improved Big Creek's ability to provide peaking power (electricity needed during high demand). This brought the project's total power generation capacity to its current level.

Project Details and Numbers

The Big Creek Project is made up of many connected parts. Here's how the main parts work:

- The dam at Florence Lake collects water from the South Fork San Joaquin River. This water is sent through the Ward Tunnel towards Big Creek. Water from Mono and Bear Creeks also joins this tunnel. The Vermilion Valley Dam on Mono Creek, which forms Lake Thomas A. Edison, helps control the water supply. The Ward Tunnel eventually flows into Huntington Lake, where it powers the Portal Powerhouse.

- Huntington Lake is created by Big Creek Dam Nos. 1, 2, and 3. It stores water from Big Creek and the South Fork San Joaquin River. This water is released through a tunnel, dropping 2,131 feet (649 meters) to Big Creek Powerhouse No. 1, located on a small reservoir called Dam 4. From there, the water goes through another tunnel, falling 1,858 feet (566 meters) to Big Creek Powerhouse No. 2 on Dam 5.

- Shaver Lake is on Stevenson Creek, south of Huntington Lake. It gets some water from its local area, but its main job is to store extra water from Huntington Lake. Water from Huntington goes through a tunnel to a small reservoir, Balsam Meadows Forebay, and then drops 1,338 feet (408 meters) to the Eastwood Powerhouse on Shaver Lake. When less power is needed, water is pumped from Shaver Lake back up to Balsam Meadows to be used later for peaking power. From Shaver Lake, the water falls 2,418 feet (737 meters) – the biggest drop in the whole project – to Big Creek Powerhouse 2A, which is also on Dam 5.

- From Dam 5, the combined waters flow through another tunnel and drop 713 feet (217 meters) to Big Creek Powerhouse No. 8. This powerhouse is located on Dam 6, where Big Creek meets the San Joaquin River.

- The Mammoth Pool Dam creates Mammoth Pool Reservoir on the San Joaquin River. Mammoth Pool helps control the river's flow to make more power downstream. Water flows from Mammoth Pool through a tunnel to Dam 6, where it drops 1,100 feet (335 meters), powering the Mammoth Pool Powerhouse.

- From Dam 6, the combined waters of Big Creek and the San Joaquin River fall 827 feet (252 meters) to Big Creek Powerhouse No. 3 at Redinger Dam, also known as Dam 7. From Redinger, the water flows through a final tunnel and drops 418 feet (127 meters) to Big Creek Powerhouse No. 4. This powerhouse is located on the reservoir of Kerckhoff Dam, which is part of a separate hydroelectric project owned by Pacific Gas and Electric.

Reservoirs and Forebays

| Statistics of the major reservoirs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dam(s) | Reservoir | River | Dam height |

Storage capacity |

Surface area |

Elevation | Year | |

| Big Creek Dam No. 1 Big Creek Dam No. 2 Big Creek Dam No. 3 |

Huntington Lake | Big Creek | 170 ft (52 m) |

89,800 acre.ft (110,000 dam3) |

1,440 acres (583 ha) |

6,950 ft (2,118 m) |

1913 | |

| Big Creek Dam No. 4 | Dam Four Lake | Big Creek | 75 ft (23 m) |

99 acre.ft (122 dam3) |

4 acres (2 ha) |

4,810 ft (1,466 m) |

1913 | |

| Big Creek Dam No. 5 | Dam Five Lake | Big Creek | 60 ft (18 m) |

74 acre.ft (91 dam3) |

10 acres (4 ha) |

2,943 ft (897 m) |

1921 | |

| Big Creek Dam No. 6 | Dam Six Lake | San Joaquin River | 155 ft (47 m) |

1,730 acre.ft (2,134 dam3) |

23 acres (28 ha) |

2,230 ft (680 m) |

1923 | |

| Florence Lake Dam | Florence Lake | South Fork San Joaquin River |

154 ft (47 m) |

64,600 acre.ft (80,000 dam3) |

296 acres (120 ha) |

7,328 ft (2,234 m) |

1926 | |

| Mammoth Pool Dam | Mammoth Pool Reservoir | San Joaquin River | 411 ft (125 m) |

123,000 acre.ft (152,000 dam3) |

1,100 acres (445 ha) |

3,330 ft (1,015 m) |

1959 | |

| Redinger Dam (Big Creek Dam No. 7) |

Redinger Lake | San Joaquin River | 250 ft (76 m) |

35,000 acre.ft (43,200 dam3) |

620 acres (251 ha) |

1,403 ft (428 m) |

1951 | |

| Shaver Lake Dam | Shaver Lake | Stevenson Creek | 185 ft (56 m) |

136,000 acre.ft (168,000 dam3) |

2,190 acres (886 ha) |

5,370 ft (1,637 m) |

1927 | |

| Vermilion Valley Dam | Lake Thomas A. Edison | Mono Creek | 165 ft (50 m) |

140,000 acre.ft (173,000 dam3) |

1,910 acres (773 ha) |

7,643 ft (2,330 m) |

1954 | |

| Water Data Totals | (all lakes full) | 590,303 acre.ft (727,444 dam3) |

7593 acres (3071 ha) |

|||||

Power Plants

| Powerplant statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Capacity (MW) |

Hydraulic head |

Annual generation (MWh) |

| Big Creek 1 | 88.15 | 2,131 ft (649 m) |

412,542 |

| Big Creek 2 | 66.5 | 1,858 ft (566 m) |

352,941 |

| Big Creek 2A | 110.0 | 2,418 ft (737 m) |

511,290 |

| Big Creek 3 | 174.45 | 827 ft (252 m) |

830,202 |

| Big Creek 4 | 100.0 | 418 ft (127 m) |

474,160 |

| Big Creek 8 | 75.0 | 713 ft (217 m) |

305,664 |

| Mammoth Pool | 190.0 | 1,100 ft (335 m) |

642,035 |

| Eastwood | 199.8 | 1,338 ft (408 m) |

356,342 |

| Portal | 10.8 | 230 ft (70 m) |

47,400 |

| Totals | 1,014.7 | 3,932,576 | |

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |