Bonville–Courtenay feud facts for kids

The Bonville–Courtenay feud was a big fight between two powerful families, the Courtenays and the Bonvilles. It happened in Devon, south west England, around 1455. Many noble families fought each other back then. This feud became important because both families were very powerful in English politics. The Courtenay earls usually controlled Devon. But the Bonville family grew stronger and started competing for the king's favor. This competition led to real violence, including attacks, disorder, and even a killing.

Historians often use the Bonville–Courtenay feud to show how much law and order had broken down. Some even think it helped cause the later Wars of the Roses. The feud's events often matched the political fights of the time. It is most famous for a battle at Clyst, near Exeter, where people died.

The events at Clyst made the government get involved in the politics of the West Country. This was unusual, as the government often struggled to settle noble disputes. However, William Bonville supported the Yorkists by 1455. Richard, Duke of York, was then made Lord Protector. The feud ended only when the main people involved were killed in the early years of the Wars of the Roses.

Contents

Why the Feud Started

The mid-15th century saw many private fights between noble families. These fights were part of the bigger problem that led to the Wars of the Roses. Devonshire did not have large battles, but it was still affected by this private feud. The main people involved were Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon, and William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville. The Courtenay family had been earls of Devon since 1335.

Their feud became deeply connected to national politics. But it started with problems in Devon itself. Historian Martin Cherry said in 2003 that the south west was quite lawless then. He noted that the Bonville–Courtenay feud was the most famous, but not the only example of trouble in the region.

England's Political Situation

In 1966, historian R. L. Storey suggested that the civil wars in England began because the king could not govern well. He also said law and order broke down in local areas. The Courtenay–Bonville feud is an example of this. King Henry VI became mentally ill in August 1453. This led to Richard, Duke of York, returning to court. York was the king's closest adult relative and could claim the throne. He had been sent away after a failed rebellion in 1452.

The next year, with the king still ill, York became Lord Protector. He used this power to act against his main rival, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, who was put in prison. By Christmas 1454, King Henry was better. This meant York no longer had his special power. Henry and his nobles decided to hold a big meeting in Leicester. York and his allies, Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury and his son Richard, Earl of Warwick, thought they might be charged with crimes.

They gathered an army and marched to stop the king's group from reaching Leicester. They met at St Albans. York and the Nevilles won completely. On May 22, 1455, at the First Battle of St Albans, they captured the king. They got their places in government back. York's rivals, the Duke of Somerset, the Earl of Northumberland, and Lord Clifford, were killed. The Earl of Devon was among those wounded. York was made Protector of England again a few months later.

Professor Ralph A. Griffiths blamed King Henry VI for the feud. He said the king's "thoughtless generosity" made personal rivalries worse. However, Martin Cherry warned against seeing the feud as just a small version of the civil wars. He said they were "qualitatively" different. The feud led to the Earl of Devon losing his power, not just showing his violence. Michael Hicks noted that other feuds existed. But they had different causes. For example, the Bonville–Courtenay feud was about controlling land. Other feuds, like the Berkeley–Lisle dispute, were about who inherited property. Cherry also suggested the Earl of Devon was desperate to get royal favors. He was slowly losing out to others in this competition.

Local Power Struggles

The fight between the Bonvilles and Courtenays started in Devon. They were rivals because both families owned large amounts of land in the south west. Also, both wanted favors from the king. For example, William Bonville had fought in the Hundred Years' War for King Henry VI and his father. The Earl of Devon was the king's cousin through his wife.

The Earl of Devon was the biggest landowner and highest-ranking noble in the county. But in recent years, less important nobles, like William Bonville, had gained more power. Bonville also improved his standing by marrying into noble families. He married a daughter of the Lord Grey of Ruthin. Then he married an aunt of the Earl of Devon himself.

The most important royal job in the area was managing the rich Duchy of Cornwall. Both men had held this job at different times. Tensions between them started in 1437. That year, the Earl of Devon lost the job, and William Bonville got it. The Earl of Devon did receive £100 a year from the king. But this probably did not make up for losing the main royal job. Within two years, Bonville's property was being attacked. By 1440, their relationship was "at breaking point."

Their tension showed in displays of military strength. These displays worried the government. Both men were called before the king's council. In 1441, the Earl of Devon got the job back. But it is unclear if Bonville actually gave it up. In November that year, they had an agreement to "end all [of their] differences."

A four-year period of peace followed. This might be because Bonville spent that time serving in Gascony. This may have been part of the agreement. But it was only a short peace for the region. By 1449, the Earl of Devon attacked Bonville. Bonville, now a baron for his success in France, was trapped in his castle at Taunton for a year.

Courtenay supported Richard, Duke of York, in his 1452 rebellion. He even joined York against the king. This act of disloyalty made him lose his royal jobs in the south west. He lost the Duchy of Cornwall job, which Bonville finally got for life. He also lost Lydford Castle, the Forest of Dartmoor, and the Water of Exe. So, as his ally York lost power, Courtenay lost power to Bonville in the south west.

Courtenay had started a local war against Bonville and Bonville's ally, James Butler, Earl of Wiltshire. This happened between 1451 and 1455. He raised an army of 5,000 to 6,000 men. He forced Wiltshire to leave his home. Then he went back to attacking Taunton. The attack ended only when the Duke of York arrived. York took control of the castle and forced peace between the two sides.

By April 1455, Bonville had received many royal favors. He had all the jobs the earl had lost. He also became the constable of Exeter Castle. One historian called him "the King's lieutenant in the west." The Earl of Devon had already reacted against Bonville's power. During the Duke of York's first time as Protector (1454–5), he joined the royal council.

However, the council itself did not trust him to keep the peace. They made him promise to behave well, with a £1,000 bond. He ignored this and started another fight against Bonville. This time, the Earl of Devon brought his sons. They brought a force of men into Exeter in April 1455. They tried to ambush Bonville. This led to the government making both sides promise good behavior again.

The government was now led by Courtenay's old ally, the Duke of York. It is likely that the earl then decided to stop supporting York. He chose to support the king instead. He fought (and was wounded) at St Albans on May 22 that year, on the king's side. Bonville, through his wife, was related to the Harrington family. They had close ties to the Nevilles. Bonville's new support for the Yorkists seemed to make the Earl of Devon even more violent in the county.

The Death of Nicholas Radford

From October 1455, the Earl of Devon and his sons caused trouble. They seemed to want to stop the county's administration, which Bonville was part of. For example, they used force to stop local judges from holding meetings. Then they raised a small army at Tiverton. This army was led by the Earl of Devon's oldest son, Thomas Courtenay.

This group was responsible for what R. L. Storey called "the most notorious private crime of the century." It was very violent and clearly planned. This group went to Upcott on October 23, 1455. This was the home of Nicholas Radford. Radford was a close friend and legal advisor to Bonville. He was a respected person who had been a judge in Exeter and a member of parliament. Storey suggested that because Radford was an experienced lawyer, Devon and his sons targeted him. Radford had helped Bonville escape Devon's legal actions before. In January 1455, he had given Bonville land worth £400.

Thomas Courtenay's group attacked Radford's home that night. They set fire to the wall and gates to make him come out. Radford let them in after Courtenay promised he would not be harmed. Radford seemed surprised by how many men there were. While Radford and Devon's son drank wine, Courtenay's followers "ransacked" Radford's house. They stole goods worth up to 1,000 marks. This included all his horses and the sheets from his sick wife's bed.

Courtenay persuaded Radford to come with him, saying they would meet his father. But Courtenay left Radford on the road a short distance from the house. Six of Courtenay's men then killed him. They forced Radford's servants to carry his body to the graveyard. They put it into an open grave without ceremony. The stones ready for his memorial were then dropped on the body, crushing it. This made it impossible to identify the body. This prevented an official investigation into Radford's death.

After the Killing

The killing of Nicholas Radford was just the start of more military actions. The Earl of Devon then gathered a force and took over Exeter. They acted "as if they were the city's lawful garrison." They seized the keys of the city until just before Christmas. Various houses in the city belonging to Bonville and his supporters were searched. Members of the Cathedral were arrested and forced to pay for their freedom. In one case, a man was taken from the choir while celebrating Mass.

Both Bonville and Courtenay had strong connections with the Cathedral since the 1430s. The Courtenays had helped expand it in the previous century. Their actions in 1455 were probably because Radford had put much of his wealth in the church's care. Devon saw a chance to get rich. Storey suggested he might have needed the money to pay his men. Martin Cherry noted that there were no records of the earl's military costs. This suggests his campaign paid for itself.

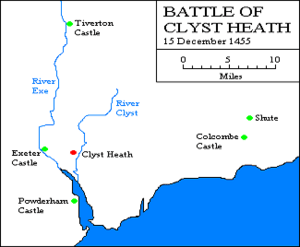

During the same time, Devon also attacked Powderham Castle. This castle belonged to his distant cousin and Bonville's ally, Sir Philip Courtenay. Philip Courtenay fought back, and Bonville came to help him. Before this, Bonville raided the Earl of Devon's house at Colcombe Castle and searched it. Bonville tried to end the attack on Powderham on November 19. But Devon pushed him back. Bonville lost two men in the fight, which may have involved up to a thousand men.

Meanwhile, Devon kept trying to get the city of Exeter to raise an army for him. They refused. He left Exeter on December 15 as Bonville approached on his way to Powderham. The two forces met at Clyst, just south west of Exeter.

The Fight at Clyst

The Earl of Devon marched from Exeter to meet Bonville at Clyst Heath. There are very few records about this event. Only one writer gives details. He said Devon "departed out of the city with his people into the field of Clyst, and there bickered and fought with the Lord Bonville and put them to flight, and so returned again that night into the city." Many bones were found when the site was dug up in 1800. However, some of these bones must belong to those killed in the 1549 event at the same place.

It is hard to say if this was a full battle. One writer estimated twelve men died. But it seems Devon won clearly. The earl returned to Exeter, where the mayor had "tactfully" planned a celebration. Hannes Kleineke called the mayor's decision to light up the city walls "pragmatic." Cherry explained the mayor's behavior by saying the earl had acted "punctiliously" towards him.

The earl later sent a small group led by Thomas Carrew to attack Bonville's home at Shute. They met no resistance and took whatever they wanted. They stole Bonville's cattle, furniture, and food. The weeks before the fight had included "formal declarations of war." These were like challenges to a duel. Michael Hicks suggested that Bonville "goaded the earl into a fair fight." He said the fight at Clyst was Bonville's fault, even though the earl had more men. Cherry also suggested that Bonville and Courtenay of Powderham tried to get the earl's former tenants to join them. This made relations even worse. Cherry said that while the earl has received "universally bad press," he was "reluctant to go to war." He only did so "after all other methods of achieving his aims... had failed."

What Happened Next

The Earl of Devon was only in prison for a few months. An attempt might have been made to put him on trial in February. But if so, it was probably stopped. This could show that York's power was "waning." The Protectorate was soon to end. Cherry said the king taking back personal power in February 1456 must have been "a considerable relief" to the earl.

The earl seemed to use the Yorkists' loss of power as a chance to continue the feud. This led to a government warning in March. His son, John Courtenay, with 500 armed men, again stopped the Exeter judges from meeting. He forced them out. Official orders were given in August. These were led by Bonville's ally, the Earl of Wiltshire.

Bonville gave the council a long list of crimes committed by Devon. He tried to lessen his own involvement. But the king was "obviously unimpressed." The king eventually put Devon back in charge of keeping the peace (September 12, 1456). He also pardoned him and his sons for their part in Radford's death. He even gave him the profitable job of keeper of the forest and park of Clarendon. The region then remained quiet. Bonville was old, and Devon might have been sick. He died in Abingdon within eighteen months. His will was handled by important members of the Queen's council.

The region did not take an active part in the civil wars until the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. But both sides of the feud were killed in the civil wars over the next few years. The new Earl of Devon, who had killed Radford, strongly supported the Lancastrian side. After the Yorkist victory at the Battle of Northampton in June 1460, he took his troops north to Margaret of Anjou in York. In April 1461, the new king, Edward IV, executed him after the Battle of Towton.

Bonville's son and grandson had been killed with the Duke of York and the Earl of Salisbury at the Battle of Wakefield in December 1460. Bonville himself was captured after the Second Battle of St Albans. He was quickly beheaded. Writers say this happened after a fake trial, likely started by the Earl of Devon.

|

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |