British airborne operations in North Africa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids British airborne operations in North Africa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tunisian campaign of World War II | |||||||

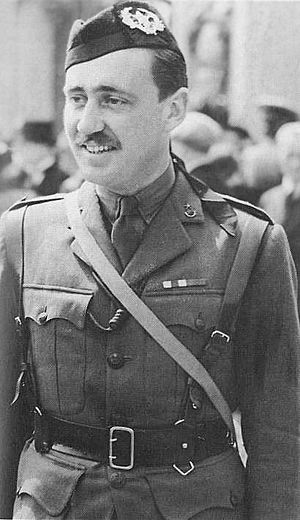

Officers of the 2nd Parachute Battalion resting near Beja after returning from a drop on Depienne. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Brigade | Various | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,700 | Unknown | ||||||

The British airborne operations in North Africa were a series of missions carried out by British paratroopers during World War II. These brave soldiers, part of the 1st Parachute Brigade, were led by Brigadier Edwin Flavell. Their actions were a key part of the Tunisian campaign, taking place between November 1942 and April 1943.

When the Allied forces planned Operation Torch, the big invasion of North Africa in 1942, they decided to include airborne troops. The 1st Parachute Brigade, which was part of the 1st Airborne Division, joined the invasion. An American airborne unit, the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, also took part. After some quick training and getting more soldiers, the brigade headed to North Africa in November 1942.

Units from the 1st Parachute Brigade made parachute jumps near Bône on November 12. They also jumped near Souk el-Arba and Béja on November 13, and at Pont Du Fahs on November 29. Their job was to capture airfields. After landing, they fought as regular infantry and joined up with Allied armored forces. They supported these forces until December.

At Pont Du Fahs, the 2nd Parachute Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel John Frost, faced a tough situation. Other British forces couldn't reach them. This meant Frost's battalion had to retreat over 50 miles to find Allied lines. They were attacked many times during their retreat. Even though they made it back safely, they lost more than 250 soldiers.

For the next four months, the 1st Parachute Brigade fought as ground troops. They were part of different army groups and moved forward with the Allied forces. They suffered many losses in some battles. But they also captured a large number of Axis soldiers. In mid-April 1943, the brigade left the front lines. They went to rejoin the rest of the 1st Airborne Division. Their next mission was to train for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

Contents

How British Paratroopers Were Formed

The German army was one of the first to use airborne troops. They had several successful parachute operations in 1940, like the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael. The Allies were impressed by this success. They decided to create their own airborne forces. This led to the creation of two British airborne divisions.

On June 22, 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked the War Office to look into creating a group of 5,000 parachute soldiers. However, there were many problems. Britain had very few military gliders, and they were too light for military use. There was also a shortage of planes to tow gliders and carry paratroopers.

By August 10, Churchill learned that 3,500 volunteers were ready to train. But only 500 could start due to lack of equipment and aircraft. The War Office thought 500 paratroopers could be ready by spring 1941. This depended on setting up a training school and getting the right equipment.

A training school for paratroopers was set up at RAF Ringway on June 21, 1940. It was called the Central Landing Establishment. The first 500 volunteers began their training there. The Royal Air Force (RAF) started designing gliders. They also turned some Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers into transport planes.

Plans were made for two parachute brigades to be ready by 1943. But there were three main problems. First, many officials thought Britain couldn't spare enough men to build an airborne force. The army was still rebuilding after the Battle of France. Second, there were not enough materials. All three military services were growing, and British industry wasn't ready to support them all. Finally, there was no clear plan for how airborne forces should be organized. There was also rivalry between the War Office and the Air Ministry (who ran the RAF). This slowed down the growth of British airborne forces.

Growing the Airborne Force

Despite these challenges, the first British airborne unit was formed by mid-1941. It was called No. 11 Special Air Service Battalion. This unit had about 350 soldiers. It was created by retraining No. 2 Commando. On February 10, 1941, 38 men from this battalion carried out the first British airborne operation. It was called Operation Colossus. They raided an aqueduct in southern Italy. The goal was to cut off water supply and hurt Italian morale.

The raid was not successful. All but one of the paratroopers were captured. But it taught the British important lessons for future missions. Soon after, it was decided to expand No. 11 Special Air Service Battalion into a Parachute Brigade. In July, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff approved creating a brigade headquarters. This included the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Parachute Battalions. It also included a small group of sappers (engineers) from the Royal Engineers.

This new group was named the 1st Parachute Brigade. Volunteers from infantry units joined starting August 31. Brigadier Richard Nelson Gale first commanded it. He was replaced by Brigadier Edwin Flavell in mid-1942. The brigade began intense training. They also tested new airborne equipment. On October 10, the 1st Airlanding Brigade joined them. This brigade had just returned from India.

Soon after, on October 29, the Headquarters 1st Airborne Division was formed. Brigadier F.A.M. Browning was in charge. He commanded the 1st Parachute Brigade, 1st Airlanding Brigade, and the glider units. Browning was promoted to Major General. He oversaw the division's growth and training. New brigades were added, and more equipment was tested.

By mid-April 1942, the division performed a small airborne exercise for the Prime Minister. Twenty-one transport planes and nine gliders took part. By late December, the division was at full strength. In mid-September, Browning learned about Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, set for November. He argued that a larger airborne force should be used. He believed the long distances and light enemy resistance would create many chances for airborne operations.

The War Office and the Commander-in-Chief agreed. They decided to send the 1st Parachute Brigade to North Africa. It would be under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The RAF couldn't provide enough transport planes. So, the United States Army Air Forces helped. They provided Douglas C-47 Dakota planes. A practice jump on October 9 had problems. Three men died because American pilots were new to British equipment. This caused delays in training. Most of the brigade went to North Africa without a training jump from a Dakota. After getting more soldiers from the 2nd Parachute Brigade and enough equipment, the brigade left for North Africa in early November.

Important Missions

Capturing Airfields at Bône

Not enough transport planes were available for the whole brigade. So, only the 3rd Parachute Battalion could go by air. This included its headquarters and two companies, 'B' and 'C'. The battalion landed at Gibraltar on November 10. Their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Pine Coffin, learned they had a mission the next day.

Pine Coffin was briefed by Lt. Gen. Kenneth Anderson, commander of the British First Army. The mission was to take off from Maison Blanche airfield. They would parachute to capture an airfield near the port of Bône. This port was on the border of Tunisia and Algeria. Allied intelligence knew German Fallschirmjaeger (paratroopers) were in Tunis. It was vital for the British to capture the airfield first. Once captured, they would hold it until No. 6 Commando arrived. The Commandos would land by sea, capture Bône, and link up with the paratroopers.

This was a tough job for Pine Coffin. His battalion didn't have enough planes for the jump. Two planes had also failed to arrive. But enough aircraft were found. At 04:30 on November 11, they took off from Gibraltar. They landed at Maison Blanche at 09:00. However, the American pilots flying the Dakotas had no experience with night drops. Finding drop zones in the dark was very hard. So, the mission was delayed until dawn on November 12.

Pine Coffin and his team planned the mission. The 29 Dakotas would fly from Maison Blanche along the coast to Bône harbor. The lead plane would fly low over the airfield to check if it was empty. If it was, the paratroopers would jump onto the airfield. If German paratroopers were there, the Dakotas would drop the companies a mile away. They would then attack the airfield. The planning finished by 16:30. At 20:00, the American pilots were briefed. A German plane flew over and dropped bombs, briefly interrupting the briefing.

The planes took off at 08:30 the next day. The flight was calm. Two planes had mechanical problems and landed in the ocean, causing three injuries. The lead Dakota flew over the airfield. It was empty. The paratroopers jumped, followed by the other planes. The drop was mostly accurate. A few supplies and paratroopers landed three miles away. Thirteen men were injured during the jump, mostly from landing. One man died when his Sten gun accidentally fired. One officer was knocked out for four days.

The British didn't know that German Junkers Ju 52 transport planes had seen their drop. These planes were carrying a Fallschirmjaeger battalion. Seeing the airfield was already taken, the German planes turned back to Tunis. After securing the airfield, the British battalion was attacked by Stuka divebombers. They had no defense at first. But once No. 6 Commando secured Bône, they found Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns from sunken ships. These guns, with Spitfire planes that arrived on November 11, helped fight off future attacks. The battalion held the airfield with No. 6 Commando until November 15. Then, they moved to Maison Blanche to join 'A' Company and the rest of the 1st Parachute Brigade.

Béja and Souk el Arba Missions

The 1st Parachute Brigade, without the 3rd Parachute Battalion, arrived in Algiers on November 12. Some of their supplies came later. By evening, scouts went to Maison Blanche airfield. The rest of the brigade followed on November 13. They stayed in Maison Blanche, Maison-Carrée, and Rouiba. On the same day, the 2nd Battalion of the American 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment joined the brigade. This battalion had arrived on November 8 and was helping the United States Fifth Army advance.

Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson, commander of the British First Army, first wanted the brigade to parachute into Tunis. This was about 500 miles behind German lines. The brigade studied the mission plans on their way to North Africa. But the plan was canceled when they arrived. Allied intelligence reported that 7,000-10,000 German troops had landed in Tunis. This made an airborne attack impossible.

With the Tunis plan canceled, on November 14, the First Army ordered a single parachute battalion to drop near Souk el-Arba and Béja the next day. The battalion's tasks were:

- Contact French forces at Beja to see if they would help the Allies.

- Secure the crossroads and airfield at Souk el Arba.

- Patrol east to bother German forces.

The 2nd Battalion of the 509th PIR would drop at the same time. Their goal was to capture airfields at Tebessa and Youks el-Bain.

The 1st Parachute Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel James Hill, was chosen for this mission. Hill objected. His battalion had to unload their own supplies and find their own transport to Maison Blanche. They had also been attacked by German planes at the airfield. Hill argued his men were tired. He didn't think all their equipment could be ready in 24 hours. He asked for a delay, but it was denied.

Hill faced more problems. The American pilots flying the Dakota planes had no experience with parachute drops. There was no time for practice. Also, there were no photos of the airfield or the area. Only one small map was available. To make sure the planes found the right spot, Hill decided to sit in the cockpit of the lead Dakota. He would help the pilot. The battalion's parachutes only arrived at 16:30 on November 14. They were packed 12 to a container and had to be repacked. But the battalion was ready by November 15. They took off at 07:30.

Four American P-38 Lightning fighters escorted the Dakotas. They fought off two German fighters. But as the Dakotas neared the Tunisian border, they hit thick clouds. They had to turn back, landing at Maison Blanche at 11:00. It was decided the battalion would try again the next day. This gave the paratroopers a night to rest. Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion of the 509th PIR successfully dropped at Tebessa. They captured their targets and secured the area. They then left the 1st Parachute Brigade's control.

The 1st Parachute Battalion took off on the morning of November 16. The weather was excellent. The planes dropped the battalion accurately around the airfield at Souk el-Arba. Most paratroopers landed well. One man died accidentally. One officer broke his leg. Four men were wounded when a Sten gun fired by mistake. The battalion's second-in-command, Major Pearson, stayed at the airfield. He collected equipment and oversaw the burial of the dead soldier.

Lieutenant Colonel Hill led the rest of the battalion, about 525 men, in borrowed trucks to Béja. This was an important road and railway center, about 40 miles from the airfield. The battalion arrived around 18:00. The local French garrison, 3,000 strong, welcomed them. Hill convinced the French to work with the paratroopers. To make it seem like he had more troops, Hill had the battalion march through town several times. They wore different hats and carried different gear each time. Soon after they entered Béja, German planes bombed the town. But they caused little damage and no injuries.

The next day, 'S' Company and some engineers went to Sidi N'Sir village, about 20 miles away. They were to contact local French forces, thought to be pro-British, and bother German forces. They found the village and the French, who let them pass towards Mateur. By nightfall, they hadn't reached the town and camped. At dawn, a German convoy of armored cars passed them. They decided to set an ambush if it returned. They laid anti-tank mines on the road. They set up a mortar and Bren guns in hidden spots.

When the convoy returned around 10:00, the lead vehicle hit a mine and exploded. This blocked the road. The other vehicles were disabled with mortar fire, Gammon bombs, and more anti-tank mines. Many Germans were killed, and the rest were captured. Two paratroopers were slightly wounded. The group returned to Béja with prisoners and some damaged armored cars. After this successful ambush, Hill sent another patrol to bother German forces. But it was called back after meeting a larger German force that caused British casualties. Béja was also bombed by Stuka divebombers. This caused civilian casualties and destroyed houses.

On November 19, Hill visited the French commander guarding a vital bridge at Medjez el Bab. He warned that his battalion would fight any German attempt to cross the bridge. Hill attached 'R' Company to the French forces to help protect the bridge. German forces soon arrived. Their commander demanded to take control of the bridge and cross it. The French refused. With 'R' Company, they fought off German attacks for several hours. The battalion got help from the American 175th Field Artillery Battalion and parts of the Derbyshire Yeomanry. But the German forces were too strong. By 04:30 on November 20, the Allies lost the bridge and the area to the Germans.

Two days later, Hill learned that a strong Italian force, including tanks, was at Gue Hill. Hill decided to attack them and try to disable the tanks. The next night, he moved the battalion, except for a small guard at Béja, to Sidi N'Sir. There, they joined French Senegalese infantry. Hill planned for the battalion's 3-inch mortars to cover 'R' and 'S' Companies as they attacked Gue Hill. A small group of sappers would mine the road behind the hill. This would stop Italian tanks from retreating.

The battalion reached the hill without problems and got ready to attack. But just before the attack, there were loud explosions from behind the hill. The anti-tank grenades carried by the sappers had accidentally exploded. All but two of them were killed. The battalion lost the element of surprise. Hill immediately ordered the two companies to advance up the hill. They reached the top and fought a mix of German and Italian soldiers. Three Italian light tanks supported the enemy.

Hill drew his revolver. With his adjutant and a few paratroopers, he advanced on the tanks. He fired shots through their viewing ports to make the crews surrender. This worked on two tanks. But when they reached the third tank, its crew fired at Hill and his men. Hill was shot three times, and his adjutant was wounded. The tank crew was quickly killed with small arms fire. Hill survived because he got quick medical help. Major Pearson took over as battalion commander. He oversaw the defeat of the remaining German and Italian soldiers. Two days later, the battalion moved from Beja to an area south of Mateur. They joined Allied ground forces and came under the command of 'Blade Force', an armored group. The battalion stayed with 'Blade Force' until December 11.

Depienne and Oudna Missions

On November 18, the 1st Parachute Brigade was ordered to prepare the 2nd Parachute Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel John Frost. They were to drop near the coastal city of Sousse. The goal was to stop the Axis from using the nearby port and airfield. Only a few transport planes were available. So, two companies would take off from Maison Blanche at 11:00 on November 19. The rest of the battalion would follow the next day. The mission was expected to last ten days.

However, the operation was delayed for 24 hours on November 18, and again on November 19. During this time, the 3rd Parachute Battalion arrived at Maison Blanche. The airfield itself was attacked by Axis planes. This caused casualties among the paratroopers and damaged several aircraft. Finally, on November 27, the brigade was ordered to prepare the 2nd Parachute Battalion for a parachute drop near Pont du Fahs. They were to stop the Axis from using it. They would also raid airfields at Depienne and Oudna to destroy enemy aircraft. The battalion would then link up with ground forces from the British First Army. These forces would be advancing towards the battalion's position.

At 23:00 on November 27, the operation was delayed for 48 hours. On the night of November 28, the brigade learned that Pont du Fahs was already occupied by parts of the 78th Infantry Division. Despite this, and problems getting aerial photos of the landing zones, the brigade was ordered to drop the 2nd Battalion at Depienne airfield. The battalion was to destroy all aircraft there and at Oudna airfield. They were also to cause 'fear and despair' among nearby Axis troops. Then, they would link up with British First Army ground forces advancing towards Tunis.

On the morning of November 29, the 530-strong battalion boarded 44 transport planes and took off for Oudna. There hadn't been enough time to scout the airfield from the air. So, Lieutenant Colonel Frost had to choose a landing zone from his lead aircraft. Luckily, he found a clear, open space near the airfield. The airfield had been left by the Germans. The landing for the battalion was spread out but unopposed. Seven men were injured during the drop, and one died.

The airfield was secured after the battalion gathered. A platoon from 'C' Company stayed at the airfield to guard the wounded and the parachutes. At midnight, the rest of the battalion moved towards Oudna. They only had a few hand-drawn mule carts for transport. By 11:00 on November 30, the battalion could see the Oudna airfield. At 14:30, they advanced and reached the airfield. But it too had been abandoned. The battalion was then attacked by German tanks, supported by fighters and Stuka divebombers. The Germans were pushed back. But at dusk, Frost pulled the battalion back west to a better defensive spot. He hoped to wait for British First Army units to arrive.

However, these units did not arrive. In a radio message received at dawn on December 1, Frost learned that the Allied push towards Tunis had been delayed. A short while later, a German armored column was seen advancing from Oudna. Frost decided to set an ambush. But the lead German vehicles surprised some paratroopers filling water bottles at a well. The ambush started too early, causing only one German casualty. The battalion was short on men after losses at Oudna. They were also low on ammunition. But they managed to drive off the column with mortar fire. This was only a brief break.

Two armored cars and a tank were seen moving towards the battalion from a different direction. They reportedly had British First Army markings. Frost sent a group to greet the vehicles. But they were taken prisoner. It turned out the vehicles were German with captured equipment. The German commander sent one of the captured paratroopers with a message demanding Frost surrender. Frost refused. Instead, he ordered the radios and mortars destroyed. The battalion would retreat west towards Allied lines, about 50 miles away.

The battalion managed to retreat to higher ground. But they suffered many casualties from the German armor as they moved. Now on high ground, a ridge with two small hills, the paratroopers were attacked by tanks and infantry. Heavy mortar fire supported the attack. The battalion suffered many losses. But they were saved by German aircraft. The German planes mistakenly attacked their own troops, thinking they were paratroopers. They knocked out several tanks and caused heavy German casualties.

The battalion had now lost about 150 men. Frost decided the battalion would retreat west again. The wounded would be left behind with a small guard. At nightfall, each company would try to reach Massicault village. On the night of November 31/December 1, the battalion began its retreat. They moved as fast as possible. But many paratroopers got lost and were captured by German forces chasing them.

By December 2, Battalion Headquarters, Support Company, and attached sappers, led by Frost, reached an Arab farm. They joined 'A' Company, forming a group of about 200 men. However, many paratroopers were still missing. German forces soon found and surrounded Frost and his men. A fierce battle began. Because the paratroopers were so low on ammunition, Frost knew the farm couldn't be held. During the night, he led a charge through the weakest part of the German defenses. Once they broke through, Frost used his hunting horn to gather the remaining paratroopers. They then marched towards the Allied-held town of Medjez el Bab. After stopping at one last farm for supplies, the group reached the town on December 3. They linked up with American patrols.

Stragglers continued to reach Allied lines over the next few days. Units from the 56th Reconnaissance Regiment helped them. But the battalion ultimately lost 16 officers and 250 other ranks killed, captured, or wounded during the mission. Historians have commented on the operation. Rick Atkinson called it a foolish mistake due to bad intelligence. Peter Harclerode made a similar point, saying the mission was "a disastrous episode, badly planned and based on faulty intelligence." For Otway, the mission "suffered from a lack of information, and from a lack of adequate arrangements for a link-up between the ground forces and too lightly armed and comparatively immobile airborne troops."

Fighting as Ground Troops

New soldiers for the 2nd Parachute Battalion arrived from Britain to replace their losses. On December 11, the battalion moved to Souk el Khemis. There, it joined the rest of the Brigade. As Frost and his men retreated from Oudna, the Brigade learned it would be used as infantry. On December 11, it came under the control of British V Corps. It moved to positions near Beda. When it arrived, No. 1 Commando and a French unit, 2e Bataillon 9e Regiment de Tirailleurs Algeriennes, were added to its command.

The brigade took up defensive positions around Beda. They sent out patrols nearby. But they stayed in a static role. On December 21, it was placed under the command of the 78th Infantry Division. The plan was to attack towards Tunis. But heavy rain canceled this operation. When it was decided that bad weather made any further attack on Tunis impossible, Brigadier Flavell asked for the brigade to be moved to the rear. He wanted it to be used again in an airborne role.

His request was denied. V Corps said there weren't enough troops to replace the brigade. So, it stayed in its positions, defending the entire Beda area. The brigade then became heavily involved in fighting across its front. The 3rd Parachute Battalion, especially, launched several attacks on a hill called 'Green Hill'. In multiple attacks, several companies from the battalion reached the top of the hill. But they were driven back by enemy counter-attacks.

On the night of January 7-8, the brigade was relieved from the front line. It was moved to Algiers. The 2nd Parachute Battalion stayed with the 78th Infantry Division because there were no troops to replace it. Plans were made to use the brigade with US II Corps. The goal was to cut Axis supply lines around Sfax and Gabes. But these plans were never completed.

On January 24, the brigade was moved back to V Corps. It came under the command of the 6th Armoured Division. But it didn't stay there long. Two days later, it came under the command of XIX French Corps, near Bou Araba. There, it was given command of several French units. It was placed between the 36th Infantry Brigade and the 1st Guards Brigade.

On February 2, the 1st Parachute Battalion was ordered to attack the mountains of Djebel Mansour and Djebel Alliliga. A company from the French Foreign Legion supported them. The battalion attacked during the night. By the next morning, they had captured both areas against strong resistance. However, heavy losses meant the battalion had to retreat from Djebel Alligila. They focused on Djebel Mansour. There, they were cut off from supplies and almost all reinforcements. Counter-attacks by the 6th Armoured Division failed to reach the battalion.

A battalion from the Grenadier Guards captured most of Djebel Alliliga on February 4. But both battalions faced increasingly heavy attacks. By 11:00 the next day, it was decided to pull both battalions back.

On February 8, the 2nd Parachute Battalion rejoined the 1st Parachute Brigade. The whole formation then came under the command of the 6th Armoured Division. Then, it was under British Y Division, a temporary division that replaced the 6th Armoured Division in mid-February. The brigade stayed in defensive positions for the rest of February. They fought off several small enemy attacks. Then, a major offensive happened on February 26. During this, they caused about 400 enemy casualties and took 200 prisoners. This cost them 18 killed and 54 wounded paratroopers.

On March 3, the brigade was replaced by the 26th US Regimental Combat Team. It marched to new positions along the road between Tamara and Sedjenane. The brigade then held these positions against several attacks on March 8-9. They took almost 200 prisoners. On March 10, Brigadier Flavell was given command of all forces in the brigade's area. This included the 139th Brigade and No. 1 Commando. The entire force fought off several more attacks.

On the night of March 17, however, the entire force had to retreat several miles to new positions. A very strong attack broke through the positions held by the 139th Brigade and several French battalions. These new positions were held against more enemy attacks and secured by March 19. The 2nd and 3rd Parachute Battalions were put in reserve on March 20. Brigadier Flavell asked for this, saying the brigade was tired and needed rest.

However, the 3rd Parachute Battalion was ordered back to the front on March 21. They were tasked with attacking a feature called 'The Pimple'. A previous attack had failed with heavy losses. They attacked that night. But they had to pull back by dawn the next day after running out of ammunition and suffering many casualties. 'The Pimple' was seen as a vital position for a big Allied attack. So, the brigade was ordered to attack it again. The 1st Parachute Battalion did so on the night of March 23. They successfully captured it after several hours of fighting.

On March 27, the entire brigade took part in a general Allied attack. The goal was to take control of the area around Tamera. The 1st and 2nd Parachute Battalions attacked at 23:00 that day. They took many prisoners and secured their objectives. Then, they fought off a German counterattack, but with heavy losses. More heavy and confusing fighting continued. Several companies of the 3rd Parachute Battalion had to be attached to the 2nd Parachute Battalion to reinforce it. The 1st Parachute Battalion also captured its own objectives. By the end of March 29, the brigade had secured all its objectives. They had taken 770 German and Italian soldiers as prisoners.

On March 31, the brigade took up positions covering the left side of the 46th Division. For the next two weeks, they stayed in the area. They conducted many patrols but met little resistance. On April 15, the brigade was replaced by the 39th US Regimental Combat Team. It moved to the rear. Then, it traveled to Algiers on April 18 and stayed there. Brigadier Flavell left for England for a new command. Brigadier Gerald Lathbury replaced him. Soon after, the brigade rejoined the 1st Airborne Division. They began training for the airborne landings that would happen during Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

What Happened After

During its time in North Africa, the 1st Parachute Brigade captured over 3,500 enemy soldiers as prisoners of war (POWs). They also suffered more than 1,700 casualties. For example, Lieutenant Colonel John Frost's 2nd Parachute Battalion started with 24 officers and 588 other ranks. They got about 230 new soldiers in January 1943. But they left in April with only 14 officers and 346 other ranks. This means 80% of their soldiers were lost. In the 1st Parachute Battalion, only four officers stayed with the battalion through the entire Tunisian Campaign without being killed or badly wounded.

The German troops they fought gave the brigade the nickname 'Rote Teufel' or 'Red Devils'. This was a special honor. The 1st Airborne Division commander, Major-General Frederick Browning, pointed this out. He said, "Such distinctions given by the enemy are seldom won in battle except by the finest fighting troops." This title was later officially confirmed by General Sir Harold Alexander. He commanded the 18th Army Group. From then on, all British airborne troops were called 'Red Devils'.

Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway wrote the official history of the British Army's airborne forces in World War II. He looked closely at the brigade's actions. He said the airborne missions by the 1st and 2nd Parachute Battalions faced big problems. They lacked aerial photos and good maps. Also, the American air crews who dropped them were not experienced. This led to very inaccurate and scattered drops. He also believed that "a lack of an expert in airborne matters at either Allied Forces Headquarters or First Army" meant the 1st Parachute Brigade was not used as well as it could have been. This lack of knowledge meant planning and supplies before each mission could have been better.

He also argued that the brigade lacked light anti-tank weapons. And each battalion didn't have a fourth company. Not having this extra company was a "serious handicap" for each battalion, especially when surrounded by enemies. Otway thought the brigade did well in its ground role, especially with day and night patrols. But they were not used to working with other army branches, like artillery and tanks. This was because they hadn't trained together. They had to learn these skills during combat.

The brigade also suffered from a lack of new soldiers. Airborne training had very high physical and mental standards. This meant there were few new soldiers available, and the supply quickly ran out. They also didn't have their own transport. This forced the brigade to rely on captured enemy vehicles and pack animals. Finally, Otway argued that "it was most uneconomical and inefficient to employ a parachute brigade in ground operations." He felt they should only be used this way if they had enough transport and extra soldiers. Also, they needed a senior officer who understood their special role and could advise on how to use them effectively.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |