British expedition to Tibet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids British expedition to Tibet |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Game | |||||||

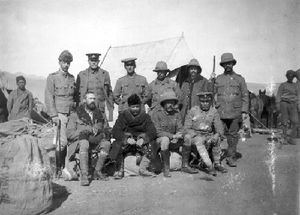

British and Tibetan officers negotiating |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| 13th Dalai Lama Dapon Tailing |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,000 soldiers 7,000 support troops |

Unknown, several thousand peasant conscripts | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 202 killed in action 411 non-combat deaths |

2,000–3,000 killed | ||||||

The British expedition to Tibet, also known as the Younghusband expedition, was a journey by the British Indian Army into Tibet. It started in December 1903 and ended in September 1904. This expedition was like a temporary invasion by British forces. Their goal was to set up diplomatic ties and solve a border problem between Tibet and Sikkim.

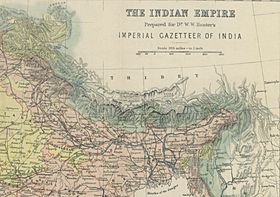

In the 1800s, Britain had taken control of Burma and Sikkim. This meant the entire southern part of Tibet was now next to the British Indian Empire. Tibet was ruled by the Dalai Lama and was under the protection of the Chinese Qing dynasty.

The British government in India, led by Lord Curzon, started this expedition. They were worried about Russia trying to gain influence in Central Asia and possibly in Tibet. Lord Curzon feared a Russian invasion of British India. Even though Russia said it had no interest in Tibet, Curzon pushed for the mission to go ahead.

The British forces fought their way to Gyantse and then reached Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, in August 1904. The 13th Dalai Lama had already left for safety. The Tibetan fighters were not well-trained or equipped. They could not stand against the modern British Indian forces. In Lhasa, the British made Tibetan officials sign the Convention of Lhasa. The British then left for Sikkim in September. The agreement stated that China would not let any other country interfere with Tibet.

The British Indian government saw this as a military mission. They even gave out a special medal, the Tibet Medal, to everyone who took part.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

The British Empire in India first met Tibet after taking over areas like Kumaon in 1815. Their influence grew as they expanded into Punjab and Kashmir. However, the British found it hard to trade or talk with Tibet. After Sikkim became a British protectorate in 1861, its border with Tibet needed to be clearly marked. Sikkim also seemed like a good way for Britain to trade with Tibet.

Chinese officials called ambans were present in Tibet. This made the British think China had power over Tibet. So, they started talking with China about relations with Tibet. But the Tibetans did not accept these agreements. This included a border settlement and a trade deal. Tibetan troops even built a fort on Sikkimese land. Protests to China did not help. The Tibetans removed border markers put up by British and Chinese officials. A British trade officer was told that Tibet did not recognize China's promises. British attempts to talk directly with Tibetans were also rejected. China's inability to make Tibet follow the agreements showed its weakness in Tibet. The British Governor-General realized that China's power over Tibet was mostly just on paper.

Also, the British government heard rumors that China had a secret deal with Russia about Tibet. They suspected Russia was sending weapons and fighters to Tibet. Russian influence in Tibet would give them a direct path to British India. This would break the chain of buffer states that separated British India from Russia. These rumors were supported by Russian explorers in Tibet. A Russian advisor, Agvan Dorjiyev, was also with the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama avoided talking with the British. But he was in touch with the Tsar of Russia through Dorjiyev. He even asked for Russian protection in 1900.

These events made Lord Curzon believe the Dalai Lama wanted Tibet to be under Russian influence. This would end Tibet's neutral position. In 1903, Curzon asked China and Tibet for talks. These talks were to happen at Kampa Dzong, a small Tibetan village. The goal was to set up trade agreements. China agreed and ordered the Dalai Lama to attend. But the Dalai Lama refused to go. He also refused to provide transport for the Chinese Amban to attend.

The Tibet Frontier Commission

Governor-General Curzon got permission from London to send a Tibet Frontier Commission. Colonel Francis Younghusband led this group. On July 19, 1903, Younghusband arrived in Gangtok, Sikkim. He began preparing for his mission.

In August 1903, Younghusband and his escort commander tried to make the Tibetans fight. The British took a few months to get ready. The expedition moved into Tibetan lands in early December 1903. This happened after a small "Tibetan hostility." This was later found to be just some Nepalese yaks and their herders being moved back across the border. Younghusband sent a telegram to the Viceroy. He claimed Russian weapons had entered Tibet. This was to get more support for the invasion. But Curzon told him to keep quiet. Curzon reminded him that the British were advancing because Tibet had broken agreements and ignored their mission.

The Two Sides

The Tibetan soldiers were mostly peasants forced into service. They lacked organization, training, and motivation. Only a few dedicated monk units fought well. But they were too few to make a difference. Their generals also seemed afraid of the British. They often fought in open areas. This allowed the British to use their modern machine guns and rifles, causing many casualties.

In contrast, the British and Indian troops were experienced. They had fought in mountainous border wars before. Their commanding officer was also very skilled.

The British force had over 3,000 fighting men. They also had 7,000 support staff like porters. This force included soldiers from the Gurkhas, Pathans, Sikhs, and Royal Fusiliers. They also had mountain artillery, engineers, and Maxim machine guns. Many Gurkha and Pathan troops were chosen. This was because they came from mountainous regions like Nepal and were used to high altitudes.

Getting Ready

The Tibetans knew about the expedition. To avoid fighting, the Tibetan general at Yatung promised not to attack if the British did not. Colonel Younghusband replied on December 6, 1903. He said they were not at war and would not attack unless attacked first. No Tibetan or Chinese officials met the British at Khampa Dzong. So, Younghusband moved forward with about 1,150 soldiers and many pack animals. They went to Tuna, 50 miles beyond the border. After waiting months there, hoping for talks, the expedition got orders in 1904 to continue towards Lhasa.

The Tibetan government, led by the 13th Dalai Lama, was worried. A foreign power was sending a military mission to its capital. So, they began gathering their armed forces.

The Expedition Begins

The British army left Gnathong in Sikkim on December 11, 1903. They were well-prepared for battle. Their commander, Brigadier-General James Ronald Leslie Macdonald, spent the winter training his troops. They had good supplies of food and shelter. In March 1904, they began their main advance. They traveled over 50 miles before meeting their first big challenge. This was at the Guru pass on March 31.

The Chumik Shenko Clash

A military clash happened on March 31, 1904. It became known as the Chumik Shenko incident. A Tibetan force of 3,000 men blocked the road. They had old matchlock muskets and were behind a 5-foot-high rock wall. On the slope above, they had small forts. Younghusband was asked to stop, but he said the advance must continue. He would not let Tibetan troops stay on the road. The Tibetans would not fight, but they also would not leave their positions. Younghusband and Macdonald decided to disarm them.

A fight started between Sikh soldiers and Tibetan guards. A Tibetan general fired a pistol, hitting a Sikh in the jaw. British accounts say this made the Sikh soldiers react violently. Soon, fire came from three sides on the Tibetans behind the wall. Some accounts from the Tibetan side say the British tricked them or fired without warning. However, there is no proof of trickery. The old Tibetan weapons were not very useful in this situation. The British, Sikh, and Gurkha soldiers were protected by a high wall. None of them were killed.

The Tibetan forces reached safety about half a mile from the battlefield. Brigadier-General Macdonald allowed them to leave. They left behind between 600 and 700 dead and 168 wounded. Most of the wounded became prisoners in British hospitals. British casualties were 12 wounded. During this battle, Tibetans wore amulets. Their lamas had promised these would protect them. After the battle, surviving Tibetans were confused about why the amulets did not work. Younghusband sent a message to his superior. He hoped the "tremendous punishment" would stop further fighting and make them negotiate.

Moving Towards Gyantse

After the first barrier, Macdonald's force moved quickly. They crossed abandoned defenses at Kangma a week later. On April 9, they tried to go through Red Idol Gorge. This gorge was fortified to stop them. Macdonald ordered his Gurkha troops to climb the steep hillsides. They were to drive out the Tibetans on the cliffs. A fierce blizzard started, stopping all communication with the Gurkhas. Hours later, the Gurkhas had found a position above the Tibetans. Faced with fire from both sides, the Tibetans retreated. They came under heavy fire from British artillery. They left behind 200 dead. British losses were very small again.

After this fight, the British military pushed on to Gyantse. They reached it on April 11. The town's gates were open, as the Tibetan soldiers had already left. Francis Younghusband wrote to his father, "As I have always said, the Tibetans are nothing but sheep." The townspeople continued their daily lives. The British explored the monastic complex, the Palkor Chode. The main building was the Temple of One Hundred Thousand Deities. It was a nine-story stupa. Officers shared out small statues and scrolls. Younghusband's team stayed in a country house called 'Changlo Manor'. This became their headquarters. They even planted a vegetable garden. The mission's doctor helped local people, performing operations for cleft palates. Five days after arriving, Macdonald ordered the main force to go back to New Chumbi. This was to protect the supply line.

Younghusband wanted to move the mission to Lhasa. He asked London for permission but got no reply. In Britain, people were shocked and worried about the events at Chumik Shenko. Magazines like The Spectator and Punch criticized the killing of "half-armed men" with modern weapons. Meanwhile, Younghusband learned that Tibetan troops had gathered at Karo La, 45 miles east of Gyantse.

Lt. Colonel Herbert Brander, commander at Changlo Manor, decided to attack the Tibetan force at Karo La. He did this without asking Brigadier-General Macdonald. Brander asked Younghusband, who supported the attack. Perceval Landon, a reporter for The Times, thought it was a bad idea to attack. Brander's plan reached Macdonald on May 3. He tried to stop the attack, but it was too late. The battle at Karo La on May 5–6 was fought at a very high altitude (over 5,700 meters). Gurkha and Sikh soldiers won this battle.

Mission Under Attack

Meanwhile, about 800 Tibetans attacked the Changlo garrison. The British staff had time to get ready and push back the attackers. The Tibetans lost 160 dead. Three British men were killed. An exaggerated story of the attack made Younghusband seem like a hero. But Younghusband's own account showed he had hidden for safety. The Gurkhas' light mountain guns and Maxims were needed to defend the fort. But Brander's Karo La party had taken them. Younghusband told Brander to finish his attack at Karo La and then return to help the garrison. The unprovoked attack on the mission and the Tibetans taking back the Gyantse Dzong actually helped Younghusband's goal. He wrote privately that the Tibetans had "played into our hands." He told Lord Ampthill that the need to go to Lhasa was now clear.

After the May 5 attack, the mission was constantly fired upon from the Dzong. The Tibetan weapons were not very effective. But they kept up pressure, and British soldiers were killed regularly. The garrison fought back. Some mounted infantry returned from Karo La with new rifles. They chased Tibetan horsemen. A Maxim machine gun was placed on the roof. It fired short bursts at targets on the Dzong walls.

The attack on Changlo Manor made the British and Indian Governments send more help. British troops from Lebong, the 1st battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, were sent. Also, six companies of Indian troops, a party with two Maxim guns, and mountain artillery were sent. They also sent two field hospitals. The Royal Fusiliers joined Macdonald at New Chumbi in early June.

Events at Gyantse and Beyond

Important events during this time included fighting on May 18–19. The British tried to take a building from the Tibetans between the Dzong and the mission post. They succeeded. About 50 Tibetans were killed. The building was renamed the Gurkha House. On May 21, Brander's fighters went to Naini village. The Tibetans occupied a monastery and a small fort there. There was heavy fighting. But Brander's men had to return to defend the mission. The mission was under attack from the Dzong. This attack was stopped by the mounted infantry. It was the last serious attempt by the Tibetan commander to take Changlo Manor. On May 24, a company of Sikh pioneers arrived. Captain Seymour Shepard, a respected officer, also reached Gyantse. This raised British morale. On May 28, he was involved in an attack on Palla Manor. 400 Tibetans were killed or wounded. No more attacks were planned until Macdonald returned with more troops. Brander focused on strengthening the three British positions. He also reopened the supply line to New Chumbi.

By now, Lord Kitchener, the Commander-in-Chief in India, wanted Brigadier-General Macdonald to be in charge of the mission at all times. People in Simla felt Younghusband was too eager to go straight to Lhasa. Younghusband left for New Chumbi on June 6. He sent a telegram saying, "we are now fighting the Russians, not the Tibetans." He also sent many letters claiming strong evidence of Russian support for Tibet. These claims were not true. Lord Ampthill, acting as Viceroy, ordered Younghusband to restart talks with the Dalai Lama. Younghusband reluctantly sent an ultimatum to the Dalai Lama and the Chinese amban. He arrived at New Chumbi on June 10. Macdonald and Younghusband discussed their differences. On June 12, the Tibet Field Force marched out of New Chumbi.

Once Gyantse Dzong was cleared, the road to Lhasa would be open. Gyantse Dzong was a very strong fortress. It was too strong for a small force to capture. Since it overlooked British supply routes, it became Macdonald's main target. On June 26, a fortified monastery at Naini was taken by Gurkha and Pathan soldiers. Tibetan forces in two forts in the village were caught between two fires. The garrison at Changlo Manor joined the fight. On June 28, the Tsechen monastery and its fort were cleared. This removed the last obstacle to attacking Gyantse Dzong. Since the monastery resisted, it was looted. Valuable artworks were later sold.

So far, Tibetan responses to the invasion were mostly static defenses and sniping. Neither tactic worked well. Besides the failed attack on Changlo two months earlier, the Tibetans had not attacked British positions. This was due to fear of the Maxim Guns and faith in their strong defenses. But in every battle, they were let down by their poor weapons and inexperienced officers.

On July 3, a formal meeting was held. The Tibetan delegation was told by Younghusband to leave the Dzong in 36 hours. Younghusband did not try to negotiate. Meanwhile, General Macdonald was criticized. Some officers wanted him replaced by a "fighting general."

Storming Gyantse Dzong

The Gyantse Dzong was a very strong fortress. It was defended by the best Tibetan troops and their only artillery. It stood high over the valley. Macdonald made a fake attack on the western side of the Dzong. This was to draw Tibetan soldiers away from the south side, which was the main target. Artillery would then create a hole in the wall. The main force would then storm this hole. The old Tsechen monastery was burned to prevent Tibetans from using it again.

The main attack on July 6 did not go as planned. The Tibetan walls were stronger than expected. Macdonald's plan was for infantry to attack in three groups. But at the start, two groups accidentally ran into each other in the dark. It took eleven hours to break through. The hole in the wall was not ready until 4:00 pm. This left little time before nightfall. As Gurkhas and Royal Fusiliers charged the broken wall, they faced heavy fire and suffered casualties. Gurkha troops climbed the rock directly under the upper walls. Rocks rained down on them. Some Gurkhas were even hit by friendly fire from a Maxim gun. After several failed attempts, two soldiers broke through a narrow spot. They were both wounded but gained a foothold. Other troops followed, allowing them to take the walls. The Tibetans retreated in an orderly way. This gave the British control of the road to Lhasa. But it meant the Tibetans remained a threat behind the British lines.

The two soldiers who broke the wall at Gyantse Dzong were rewarded. Lieutenant John Duncan Grant received the only Victoria Cross of the expedition. Havildar Pun received the Indian Order of Merit first class. A medical officer said the Gurkhas' storming of the breach was an amazing feat.

Soldiers looted Palkor Chode, Dongtse, and other monasteries after Gyantse Dzong fell. Even though rules said not to, looting seemed acceptable if the army felt they had been resisted. Some looting was even officially approved.

Reaching Lhasa

On July 12, engineers tore down the Tsechen monastery and fort. On July 14, Macdonald's force marched east towards Lhasa.

At the Karo La pass, Gurkhas fought a determined group of Tibetans. But resistance mostly faded. The Tibetans used a scorched earth tactic. They removed all food and supplies and emptied villages. Still, the troops could fish in the lakes. They passed along the shores of the Yamdok Tso. They reached the fortress of Nakartse, which was empty except for some delegates from Lhasa. Macdonald urged Younghusband to settle things. But Younghusband would only negotiate in Lhasa. By July 22, the troops camped near another ruined fortress. Mounted infantry went ahead to take the crossing at Chushul Chakzam, the Iron Bridge. On July 25, the army began crossing the Tsangpo river. This took four days.

The force arrived in Lhasa on August 3, 1904. They found that the 13th Dalai Lama had fled to Mongolia. The Chinese Amban escorted the British into the city. But he said he had no power to negotiate. The Tibetans told them only the absent Dalai Lama could sign any agreement. The Amban advised the Chinese emperor to remove the Dalai Lama from power. The Tibetan Council of Ministers and the General Assembly started to give in to pressure on the treaty terms in August. But they found the demand for payment impossibly high for a poor country. Eventually, Younghusband pressured the regent and the Tibetan National Assembly. They signed a treaty on September 7, 1904. This was known as the Convention of Lhasa. It was signed at the Potala Palace, as Younghusband insisted. He wrote to his wife that he had forced the whole treaty on them.

The Anglo-Tibetan Convention of Lhasa

The main points of the Convention of Lhasa of 1904 were:

- The British could trade in Yatung, Gyantse, and Gartok.

- Tibet had to pay a large amount of money (7,500,000 rupees). This was later reduced by two-thirds. The Chumbi Valley would be held by Britain until the money was paid.

- The border between Sikkim and Tibet was recognized.

- Tibet was not allowed to have relations with any other foreign powers.

The amount of money Tibet had to pay was the hardest part for the Tibetan negotiators. The British Secretary of State for India had said the amount should be "within the power of the Tibetans to pay." Younghusband had the freedom to decide the amount. He raised the demand from 5,900,000 to 7,500,000 rupees. He also demanded that a British trade agent at Gyantse could visit Lhasa for "consultations." It seems he wanted to extend British influence in Tibet by keeping the Chumbi Valley. Younghusband wanted the payment to be made yearly. It would have taken about 75 years for Tibet to pay. Since Britain would occupy the Chumbi Valley until payment was complete, the valley would stay in British hands. Younghusband wrote to his wife after signing, "I have got Chumbi for 75 years. I have got Russia out for ever."

The Chinese Amban later publicly rejected the treaty. Britain said it still accepted China's claims of power over Tibet. The acting Viceroy, Lord Ampthill, reduced the payment by two-thirds. He also made the terms easier in other ways. The terms of this 1904 treaty were changed in the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906. The British agreed not to take Tibetan land or interfere in Tibet's government. This was for a fee from China. China, in turn, promised not to let any other foreign country interfere with Tibet.

What Happened Next

The British mission left in late September 1904. Britain had "won" and got the agreements it wanted. But they did not get any real, lasting results. The Tibetans lost the war. But they saw China humbled by its failure to protect Tibet. They calmed the British by signing a treaty that was hard to enforce and not very important. Captured Tibetan troops were released without conditions after the war. Many received medical treatment.

The reaction in London was very critical of the war. By the early 1900s, colonial wars were becoming unpopular. People and politicians were unhappy about fighting a war for such minor reasons. They also criticized the first battle, calling it a deliberate massacre of unarmed men. Only with support from King Edward VII were Younghusband, Macdonald, and others praised for the war. The British lost 202 men killed in action and 411 to other causes like disease. Tibetan casualties are estimated at 2,000 to 3,000 killed or fatally wounded.

Younghusband became the head of Kashmir after the campaign. But his judgment was no longer trusted. Political decisions were made without him. Once Lord Curzon's protection was gone, Younghusband had no future in Indian politics. He retired from India at age 46.

Aftermath

The Tibetans were not only unwilling to follow the treaty, but they also could not meet many of its demands. Tibet did not have much international trade. It already accepted its borders with neighbors. Still, the terms of the 1904 treaty were confirmed by the 1906 Anglo-Chinese Convention between Britain and China. The British agreed not to take Tibetan land or interfere in Tibet's government. This was for a payment from China. China, in turn, promised not to let any other foreign country interfere with Tibet.

The British invasion helped trigger the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion at Batang monastery. In this revolt, anti-foreign Tibetan lamas killed French missionaries, Chinese officials, and Christian converts. China later crushed the revolt.

The British continued to occupy the Chumbi Valley until February 8, 1908. This was after China paid the full amount of the indemnity.

In early 1910, Qing China sent its own military expedition to Tibet to rule directly. However, the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution in 1911. Chinese forces left in 1913. But World War I and the Russian Revolution isolated Tibet, which was now independent. This reduced Western influence. Ineffective regents ruled during the 14th Dalai Lama's childhood. China began to regain control. This led to the Chinese invasion of Tibet by Communist China in 1950–1951.

The position of British Trade Agent at Gyantse existed from 1904 until 1944. It was not until 1937 that a British officer had a permanent post in Lhasa itself.

The British seemed to have misunderstood the situation. Russia did not have the plans for India that the British imagined. The campaign was not really needed before it even began. Russian weapons in Tibet were only about thirty rifles. The whole idea of Russian influence and the Tsar's plans was dropped. Russia's defeats in the Russo-Japanese war in 1904 also changed how power in Asia was seen. However, some argue that the campaign had a "profound effect upon Tibet." It changed Tibet forever, and not for the better. It contributed to Tibet losing its innocence.

See also

- Tibetan Expedition of Islamic Bengal

- Tibet under Qing rule

- Chinese expedition to Tibet (1720)

- Chinese expedition to Tibet (1910)

- The Great Game

- Perceval Landon

- John Duncan Grant

- Frederick Percival Mackie

- Sikkim Expedition

- Red River Valley, a 1997 Chinese movie about the events of the British expedition to Tibet

- Sinicisation of Tibet

- Tibetan government in exile

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |