Brother Jonathan (steamer) facts for kids

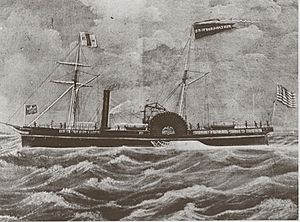

Brother Jonathan after the 1861 refit

|

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Owner |

|

| Completed | 1851 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 1359 52/95 tons burthen |

| Length | 220 ft 11 in (67.34 m) |

| Beam | 36 ft (11 m) |

| Depth | 21 ft (6.4 m) |

| Sail plan | barkentine |

|

Brother Jonathan (Shipwreck Site)

|

|

Brother Jonathan in 1851

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | About 4.5 mi (7.2 km) SW of Point St. George |

| Nearest city | Crescent City, California |

| NRHP reference No. | 02000535 |

| Added to NRHP | May 21, 2002 |

The Brother Jonathan was a large paddle steamer that sank off the coast of Crescent City, California, on July 30, 1865. It hit a hidden rock near Point St. George. The ship was carrying 244 people and a lot of gold. Only 19 people survived the disaster. This made it the deadliest shipwreck on the Pacific Coast of the United States at that time. Experts believe 225 people died. The ship's location was a mystery until 1993. Some of its valuable gold was found in 1996.

Contents

Building a Ship for the Gold Rush

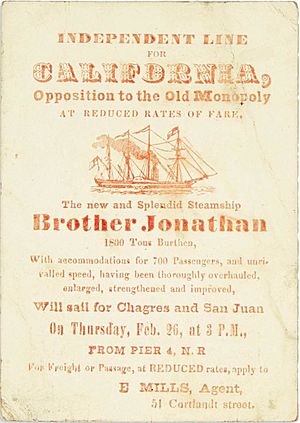

The Brother Jonathan was built in 1851 for Edward Mills. He was a businessman from New York. Mills wanted to run a shipping business during the California Gold Rush. The ship was named after Brother Jonathan, a character who represented the New England area.

When it was built, the ship was about 220 feet long and 36 feet wide. Its first route was from New York to Chagres, Panama. On its first trip, it set a record for the fastest round-trip, taking only 31 days. Passengers would then cross the Isthmus of Panama. From there, they would take another ship north to California.

In 1852, a famous businessman named Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the ship. He owned a rival shipping company. Vanderbilt needed a new ship because one of his had been wrecked. He had the Brother Jonathan sail all the way around Cape Horn to the Pacific side. Vanderbilt also changed the ship to carry even more passengers.

The Ship's Many Journeys

Vanderbilt's company had a special deal to carry passengers across Panama through Nicaragua. But in 1856, the Nicaraguan government ended this agreement. The ship was then sold to Captain John Wright. He renamed it Commodore. It started sailing on West Coast routes. This included trips from its new home port of San Francisco to British Columbia. Many gold miners were traveling there for the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush.

The ship also played a small but important part in Oregon's history. On February 14, 1859, President James Buchanan signed a bill making Oregon a state. The news was sent by telegraph to St. Louis. Then it traveled by stagecoach to San Francisco. On March 10, the news was loaded onto the Commodore. The ship arrived in Portland on March 15. It delivered the official news that Oregon was now a state.

By 1861, the ship was getting old and needed repairs. It was sold again to the California Steam Navigation Company. They fixed it up and gave it back its original name, Brother Jonathan. It continued sailing north from San Francisco to Vancouver, stopping in Portland. This route helped miners reach the Salmon River Gold Rush. For several years, the Brother Jonathan was known as one of the best ships on the Pacific Coast. It was the fastest, completing the trip in just 69 hours each way.

However, in the summer of 1865, the ship crashed into another vessel on the Columbia River. This damaged its hull. Captain Samuel DeWolf, who had just taken command, suggested the ship be repaired in a dry dock. But the company decided to fix it while it was still in the water. They had too much business and cargo waiting.

The Tragic Shipwreck

On its final trip, the ship was very heavily loaded. Captain DeWolf's widow later said he felt the ship was sitting too low in the water. He was told he would be fired if he didn't sail. When it was time to leave, the ship was stuck in the mud. They had to wait for high tide and a tugboat to pull it out. However, later historians found that the actual load was not as heavy as thought. It was well below the ship's carrying limit.

Just hours after leaving San Francisco Bay for Portland and Victoria, British Columbia, the ship sailed into a strong storm. Most passengers felt seasick and stayed in their cabins. Early on Sunday morning, July 30, 1865, the ship stopped in Crescent City harbor. This was the first part of its journey. After leaving the safety of the bay that afternoon, the storm got worse. The waves were so bad near the California-Oregon border that the captain decided to turn back. He wanted to return to Crescent City harbor.

Fifty-five minutes later, as the ship was close to port, it hit a hidden rock. This tore a big hole in the hull. A heavy ore crusher in the cargo hold also crashed through the already damaged part of the hull. Within five minutes, the captain knew the ship was sinking. He ordered everyone to leave the ship.

There were enough lifeboats for everyone on board. But only three boats could be launched in the rough seas. People showed great bravery and desperation. The first lifeboat was overturned by waves. The second was smashed against the ship's side. Only one surfboat made it safely to Crescent City. It carried eleven crew members, five women, and three children. Four other boats in the harbor tried to reach the sinking ship. But the storm was too strong, and they had to turn back.

Many important people were among the victims, including:

- Brigadier General George Wright, a high-ranking Union Army officer.

- Dr. Anson G. Henry, a government official and a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln.

- James Nisbet, a well-known publisher. He wrote a love note and his will while waiting for the ship to sink.

- William Logan, who was supposed to run a mint (a place where coins are made) in Oregon. His death contributed to the mint never opening.

For its last trip, the ship carried many crates of gold coins. This included money for Indian tribes, Wells Fargo shipments, and gold carried by passengers. A large ship's safe held jewelry, more gold coins, and gold bars. The gold alone was worth about $50 million in today's money. People started searching for the sunken treasure two weeks after the disaster. But for over 125 years, the gold and other items were not found. A fisherman in the 1930s claimed to have found 22 pounds of gold bars in his nets. He kept it a secret until 1974 because it was illegal to own gold bars then.

Finding the Lost Treasure

The Brother Jonathan sank only 8 miles from Crescent City. But storms, rocky areas, strong currents, and dark underwater conditions made it impossible to find. Technology needed to improve, and explorers had to change their ideas about where the ship might be. On the last day of their 1993 search, a group called Deep Sea Research (DSR) decided the ship had drifted underwater. They thought it landed 2 miles from where it hit the rock.

Led by Donald Knight, whose father had found a piece of the wreck, a mini-sub found the ship on October 1, 1993. It was exactly where they predicted. Over time, the team began bringing up artifacts from a depth of 275 feet.

In 1996, a mini-sub saw something shiny on the seabed. On August 30, 1996, divers found 875 gold coins from the 1860s. They were in almost perfect condition. Eventually, the salvors (people who recover sunken items) found 1,207 gold coins. Most were $20 double eagles.

Thousands of other items were also brought up. These included 19th-century sherry glasses, porcelain plates, beer mugs, and terracotta containers. There were also glass containers, cruet bottles, and wine bottles. Crates of goods like axe handles and doorknobs were found too.

While the recovery was happening, there were many lawsuits. The salvors, the State of California, and coin experts argued over who owned the treasure. California said it owned the wreck and everything near its shores. The state had a law that gave it rights to "historical shipwrecks." It fought against the salvors' claims. Many judges disagreed with California. Other states with similar laws joined the legal fight. Finally, in 1998, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that federal law was more important. They said California's law was unconstitutional and ruled for the salvors. However, California officials still wanted to fight. In the end, the state received 20 percent of the recovered gold. It also gained ownership of the wreck itself.

The first legal sale of gold from a sunken treasure ship happened on May 29, 1999. More than 500 people attended the auction in Los Angeles. The sale of 1,006 coins brought in a total of $6.3 million.

The Ship's Lasting Impact

The sinking of the Brother Jonathan led to new laws. These laws aimed to make passenger ships safer. They included rules about how lifeboats could be launched from a sinking ship.

The shipwreck also led to the approval of the St. George Reef Lighthouse. This lighthouse was built to warn ships away from dangerous rocks. Its construction was finished in 1892.

A memorial for those who died is located at Brother Jonathan Vista Point in Crescent City. It is registered as California Historical Landmark No. 541. The shipwreck itself is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Deep Sea Research set up a special lab to preserve the recovered items. The local historical society in Crescent City, the Del Norte County Historical Society, runs this lab. They have been cleaning and taking care of the artifacts. They also have an exhibit about the Brother Jonathan and the items found. The ship's wheel can be seen in a restaurant in Portland.

Even though many gold coins have been found, more treasure from the Brother Jonathan is still hidden. The large safe, with its millions of dollars in jewels, gold bars, and more gold, was never found. The salvors believe that about four-fifths of the treasure is still waiting to be discovered, just a few miles from land.

In 2010, a folk singer named John Donovan released an album called Bells Will Ring. This title comes from his song about the shipwreck, "Brother Jonathan."

On the 150th anniversary of the shipwreck, a group called the Idaho Civil War Round Table held a special event. They honored the victims and survivors of the tragedy. A website for the Brother Jonathan 150th anniversary was also launched.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |