Burns Bog facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Burns Bog |

|

|---|---|

Aerial view of Burns Bog from the northeast

|

|

| Location | Delta, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 49°07′15″N 122°58′25″W / 49.12083°N 122.97361°W |

| Area | 3,500 hectares (8,600 acres) |

| Formed by | Sphagnum moss |

| Age | ~3,000 years |

Burns Bog is a special type of wetland called a raised peat bog. You can find it in Delta, British Columbia, Canada. It's the biggest raised peat bog and the largest undeveloped natural area in a city on the West Coast of North and South America.

Burns Bog was once much larger, but now about 3,500 hectares (8,600 acres) of it remains. This amazing place is home to over 300 kinds of plants and animals. It also hosts 175 different bird species. Some of these animals are rare or endangered. The bog is a very important stop for many birds flying along the Pacific Flyway during their long migrations.

This bog also helps control water. It acts like a giant sponge, preventing floods. It keeps nearby rivers cool and releases water during dry times. Because it's near the Fraser River and the Pacific Ocean, it's also known as an estuarine bog.

Contents

Discover the Unique Ecology of Burns Bog

What Makes Burns Bog Special?

Burns Bog is unique because it is very wet, acidic, and forms peat. It's a wetland full of different plants, animals, and insects. A key plant here is sphagnum moss. This moss can hold about 30 times its own weight in water! It loves wet, acidic places and is the main ingredient for the peat in Burns Bog.

Dead plants and other organic stuff break down very slowly in the bog. This is because there isn't much oxygen in the water, and it's very acidic.

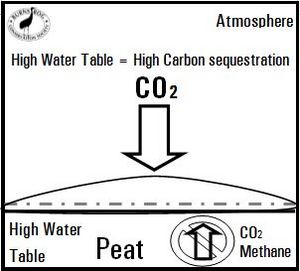

Burns Bog also helps control our climate. It cleans and cools rainwater before it flows into nearby creeks. These creeks are vital homes for salmon. The bog is also a huge "carbon sink." This means it stores a lot of carbon. Since plants break down so slowly, the carbon stays trapped in the peat. This stops it from going into the air and adding to climate change. Scientists say a peatland the size of a soccer field can store as much carbon as a family car driving around the world three times!

How Burns Bog Was Formed

Burns Bog started forming about 10,000 years ago. This was right after the last ice age ended. Back then, huge glaciers covered the area. As the Earth got warmer, these glaciers melted. They left behind layers of sand, silt, and clay. This made it hard for water to drain away. So, a big pool of glacial water formed with nowhere to go.

About 6,000 years later, the watery environment could preserve dead plants. These plants turned into an early form of peat. At first, there was no sphagnum moss. It appeared about 3,000 years later. As more peat built up, the bog's water source changed. It went from nutrient-rich floodwater to nutrient-poor rainwater. The surface of the wetland slowly became separate from groundwater. This changed the area from a fen (which has more nutrients) into a bog. Today, you can find 12 different kinds of sphagnum moss in Burns Bog.

How Water Works in the Bog

Burns Bog gets most of its water from rainfall. Plants use this water, and some of it goes back into the air through transpiration. Having the right amount of water is super important for the bog to survive. The water level needs to be high enough for sphagnum moss to grow. If the water level drops too low, the bog can dry out forever, which harms its ecosystem.

The water level in Burns Bog changes throughout the year. It's usually high in the fall and winter. But it drops during the drier summer months.

Amazing Plants and Animals

Burns Bog has over 14 different plant groups. The most important ones are "peat-forming" plants. These plants, like sphagnum mosses, grow where the water level is high.

Some rare plants found here include cloudberries, crowberry, velvet-leaf blueberry, and bog-rosemary. You can also find carnivorous plants! Sundew plants, which eat insects, live in the conservancy area. Many skunk cabbage plants also grow in the Delta Nature Reserve during summer.

Burns Bog is a busy home for many animals. The City of Delta says it supports 175 bird species, 11 amphibian species, 41 mammal species, 6 reptile species, and over 4,000 kinds of insects. You might see the Greater Sandhill Crane, black-tailed deer, dragonflies, and eagles living here.

Beavers also live in Burns Bog. They make their homes in the banks of waterways. Other animals you might spot include the redback vole, pacific water shrew, barred owl, great blue heron, snowshoe hare, great horned owl, coyote, geese, ducks, California gull, painted turtle, red-legged frog, and woodpeckers.

Fish have been seen near the edges of Burns Bog. However, they don't live inside the bog itself. The water is too acidic and doesn't have enough oxygen for fish to survive.

The History of Burns Bog

First Nations and the Land

For thousands of years, First Nations groups used the land in Burns Bog. These groups included the Tsawwassen, Semiahmoo, Katzie, and Musqueam peoples. They would sometimes burn small areas of land. This helped different berries grow, like bog blueberries and cranberries, which were an important part of their food.

Animals from the bog also provided food. They hunted black bears, black-tailed deer, elks, and ducks. Fishing in nearby creeks added to their diet. In fact, the oldest known fishing site near Burns Bog is about 4,500 years old.

Cedar trees from the region were used by First Nations to build homes, boats, and clothing. Even totem poles were made from cedar.

First Nations people also used some plants from Burns Bog for medicine. Labrador tea, western bog-laurel, sundew plants, and sphagnum moss helped treat different health problems. For example, Labrador tea was used for sore throats and coughs. Sphagnum moss was even used as diapers and bandages.

Modern History and Protection Efforts

In 1905, two brothers, Dominic and his brother, bought the bog. They wanted to raise cattle and sheep. But the cows were too heavy and got stuck easily. Some even ate poisonous plants. So, the farm closed, and the bog was later named after Dominic Burns.

Peat mining started in Burns Bog in the 1930s. The mined peat was used for farming, making weapons, and heating homes. Two peat factories were built in the bog.

During World War II, the US Government bought peat from Burns Bog. They used it to help make firebombs. Over 100,000 bales of peat were sent to Las Vegas during the war. By the early 1940s, 70% of the bog was affected by peat mining.

Railways were also built for peat harvesting. In the 1950s, a company called Western Peat built 16 kilometers of railway. Parts of it are still there today.

Over the years, many plans were made to build on Burns Bog. In 1988, a company wanted to build a deep-sea port. But many people spoke out against it, and the plan was stopped. They tried again in 1990 and 1991, but both times the plans were rejected.

In 1995, a famous British bog expert, David Bellamy, visited Burns Bog. He was amazed by its unique ecosystem and told everyone it needed to be protected. He said if it were in Europe, it would already be safe.

In 1999, 75% of voters in Delta agreed that the government should buy Burns Bog to protect it. This led to taxpayers helping to pay for its possible purchase.

More development plans came up in 1999. This led to a big study of Burns Bog's ecosystem. The study showed that 73% of the bog needed to be protected to keep it healthy.

After a lot of public effort, four levels of government worked together. They bought 2,024 hectares (5,000 acres) of land from Western Delta Lands. This was a huge step for conservation!

Fires in Burns Bog

Dry peat can catch fire very easily and spread quickly. Fires in Burns Bog can burn underground for months because the peat is rich in methane gas. There have been large fires in Burns Bog in 1977, twice in 1990, 1994, 1996, 2005, 2007, and 2016.

The 1996 fire covered the city of Vancouver in smoke and ash for two days. It destroyed 200 hectares (490 acres) of land and cost over $200,000 to put out.

Another big fire happened on September 11, 2005. It started near the southeast edge of the bog. Smoke and ash covered the entire Lower Mainland and even reached Nanaimo on Vancouver Island. The fire grew to 200 hectares (490 acres) in three days. Firefighters used huge methods to stop it. They bulldozed firebreaks and built dikes to raise the water level. This helped put out the underground fires. Air tankers, including the world's largest water bombers, helped fight the blaze from the sky. Eight days later, the fire was mostly out.

On July 3, 2016, another fire started. It grew to 78 hectares (190 acres) in three days. More than 100 firefighters, helicopters, and air tankers worked together to fight it.

Protecting Burns Bog

The Delta community and environmental groups like the Burns Bog Conservation Society have fought to protect the bog since 1988. In 1991, they first asked for Burns Bog to be made an ecological reserve. By 1999, hundreds of letters were sent to the Delta Council asking them to save the bog.

In 2004, four levels of government teamed up. They bought 2,025 hectares (5,000 acres) of land for $73 million. These governments were the federal government, the provincial government, Metro Vancouver, and The Corporation of Delta.

Burns Bog was officially named an Ecological Conservancy Area in 2005. The main goal for this area is conservation, not public use. You need a special permit from Metro Vancouver to enter this protected part of the bog.

On September 22, 2012, Burns Bog was recognized as a Ramsar Wetland of International Significance. This means it's considered important worldwide. It's part of the Fraser River Delta Ramsar site, which is a major stop for migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway. About 250,000 migratory and wintering waterfowl, and 1 million shorebirds use this area for feeding and resting. The bog is also home to many endangered and vulnerable animal species.

What Still Threatens Burns Bog?

Today, about 525 acres (212 ha) of Burns Bog is still private land. This land isn't protected by the conservancy plan. So, it could still be used for new building projects.

New roads and buildings have cut off Burns Bog from other natural areas. Roads make it harder for animals to move safely in and out of the bog. This can lead to more injuries or deaths for animals. Highways like Highway 91 have also stopped the natural flooding and drainage that used to feed the bog. A study found that the building of Highway 91 and 99 made Burns Bog much smaller. Burns Bog acts like one big living thing. The smaller it gets, the harder it is for the whole bog to survive.

The Vancouver Landfill also poses some risks. When garbage breaks down, it creates more nutrients. This is the opposite of what a bog needs. There's also a risk that polluted water from the landfill could leak into the bog. However, engineers have designed the landfill to reduce these risks.

While logging and peat mining have stopped, the damage from the past is still felt. The City of Delta is working hard to help Burns Bog recover. Metro Vancouver and the City of Delta also work with university students to check on the bog's health.

A company called MK Delta Lands Group wants to build an industrial park in Burns Bog. Their plans include building an overpass and a new water pump to drain parts of the bog. They are offering to give other parts of their land in Burns Bog to the City of Delta. But the drainage, construction, and noise from this project could harm the bog's natural ecosystem. This proposal is still in its early stages.

Visiting Burns Bog: The Delta Nature Reserve

Most of Burns Bog is closed to the public. This is for safety and to protect the bog. But a small part of Burns Bog is open for everyone to visit! This area is called the Delta Nature Reserve, and it's about 148 acres (60 ha) big.

The Delta Nature Reserve lets you see the bog's lagg zone. This is the special area where the bog slowly changes into the surrounding ecosystems. The lagg zone is super important for keeping the bog's water level high. It's the transition between the low-nutrient bog and the more nutrient-rich areas outside. Different ecosystems work together to keep the bog healthy.

The Burns Bog Conservation Society has built over 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) of boardwalks in the Delta Nature Reserve. These boardwalks make it safe and easy for everyone to explore the bog. Since February 2017, the City of Delta has been in charge of keeping these boardwalks in good shape.