Bussell Island facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Bussell Island Site

|

|

Ceramic bowl unearthed from the "Round Grave" on Bussell Island, 6.2" diameter

|

|

| Location | Loudon County, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Lenoir City, Tennessee |

| NRHP reference No. | 78002606 |

| Added to NRHP | March 29, 1978 |

Bussell Island, once called Lenoir Island, is an island in Loudon County, Tennessee. It sits where the Little Tennessee River meets the Tennessee River, near Lenoir City, Tennessee. For thousands of years, different Native American groups lived on this island before Europeans arrived.

Today, the Tellico Dam and a fun recreation area are on part of the island. In 1978, a section of the island was added to the National Register of Historic Places. This was because of its important archaeological sites.

People first lived on Bussell Island around 3000–1000 BC, during the Late Archaic period. Experts believe the island was once the main village of Coste. This was a Mississippian-period chiefdom. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto visited it in 1540. Later, the island was part of the land of the Overhill Cherokee people.

Archaeologists dug up many artifacts on Bussell Island in 1887 and 1919. These digs showed how important the island was for history. In the 1970s, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) built the Tellico Dam. This project changed the island a lot.

Contents

Where is Bussell Island?

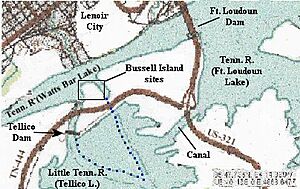

Bussell Island is located where the Little Tennessee River flows into the Tennessee River. This spot is about 601 miles (967 km) upstream from where the Tennessee River ends. The island used to stretch about a mile (1.6 km) up the Little Tennessee River.

However, the Tellico Dam was built in the 1970s. It was placed across the island's west river channel. This created a large lake that covered the southern two-thirds of the island. To hold back the water, a large dirt wall, called an earthen levee, was built. This levee runs along the island's new south shore. It also crosses the island's east river channel, connecting the island to the mainland.

The TVA also built a canal connecting two lakes: Fort Loudoun and Watts Bar. This canal cut off a part of the mainland. Now, Bussell Island is about a mile (1.6 km) long from east to west. It touches three TVA lakes: Fort Loudoun, Watts Bar, and Tellico.

Lenoir City is across the Tennessee River from Bussell Island. U.S. Route 321 (Lamar Alexander Parkway) crosses the island's new eastern part. State Route 444 (Tellico Parkway) goes through the middle of the island. These two roads meet at the island's eastern tip. US-321 crosses over the J. Carmichael Bridge, which goes over both Fort Loudoun Dam and the canal.

In 1887, an archaeologist named John W. Emmert studied the island. He said the original island was about 200 acres (81 hectares) in size. It rose up to 15 feet (4.6 m) above the river. Emmert described the island's edges as "steep" with "heavy timber and much cane growing along them." He also noted that the island would sometimes flood. One flood even stopped his work, covering the island with up to 12 feet (3.7 m) of water.

Island's Past: A Timeline

Early People: The "Round Grave" Culture

The first known people to live on Bussell Island were from the Late Archaic period. This was around 3000 to 1000 BC. They lived on the island off and on through the Woodland period (1000 BC – 1000 AD).

Archaeologist Mark R. Harrington dug here in 1919. He worked for the Heye Foundation. He called these early people the "Round Grave" people. This was because they buried their dead in small, round graves. These people used tools made from animal bones and stone. They also used bowls made of steatite and simple pottery.

The Mississippian Culture

After the "Round Grave" people, another group lived on Bussell Island. Harrington called them the "Second Culture." We now know they were part of the Mississippian culture. This culture was very active in the upper Tennessee Valley between 900 and 1600 AD.

The Mississippian people in this area built large earth mounds. These included flat-topped platform mounds and cone-shaped burial mounds. Several of these mounds were found on Bussell Island and nearby land. The Mississippian people on Bussell Island used triangular flint arrowheads and celt axes. They also wore jewelry made from copper and seashells. The seashells suggest they traded with people living near the coast.

The Village of Coste

In 1540, the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto led an expedition. He traveled across what is now the Southeastern United States, looking for a route to Mexico. De Soto traveled north from Florida. He went through modern South Carolina and North Carolina. Then, he turned west and crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains. He entered East Tennessee through the Nolichucky Valley.

After resting at a large village called Chiaha (near modern Douglas Dam), De Soto continued his journey. He followed the French Broad River and Tennessee River. He reached the village of Coste, which was centered around Bussell Island, on July 1, 1540.

De Soto had a friendly meeting with the chief of Coste on July 2. But things quickly went wrong. The Spanish took supplies from the Costeans' storage buildings. Then, some Costeans attacked the Spanish with clubs. De Soto tricked the chief and held him hostage for several days. The chief then promised to give guides and porters to the expedition. De Soto left on July 9. The expedition continued up the Little Tennessee River to the village of Tali (near modern Vonore). They eventually went south to Coosa, a chiefdom in northern Georgia.

The people of Coste spoke a Muskogean language. This language was similar to what the later Muscogee (Creek) and Koasati tribes spoke. Some experts think the name "Koasati" might come from "Coste." Coste was likely part of the Coosa chiefdom's area of influence. This area stretched from the upper Tennessee Valley south into central Alabama. In 1567, another Spanish explorer, Juan Pardo, visited other villages further up the Little Tennessee Valley. However, he turned back before reaching Coste.

Cherokee and Later History

In the mid-1700s, more than a dozen Cherokee villages grew along the lower 55 miles (89 km) of the Little Tennessee River. English colonists called these the Overhill towns. Some famous ones were Chota and Tanasi. The village of Mialoquo, the lowest of the Overhill towns, was about 17 miles (27 km) upstream from Bussell Island.

In 1761, an Anglo-American named Henry Timberlake traveled up the Little Tennessee River on a peace mission. He met a Cherokee leader near the mouth of the Little Tennessee. While Timberlake's writings and map were very detailed, he did not mention Bussell Island by name.

For most of the 1800s, Bussell Island was known as "Lenoir Island." It was named after William Ballard Lenoir. He started a large farm and a cotton mill in what is now Lenoir City. In 1887, John W. Emmert did the first big archaeological digs on Bussell Island. He worked for the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology.

By the time Mark Harrington dug on the island in 1919, the Bussell family owned it. They ran a ferry service from the opposite river shore in Lenoir City. Harrington found many Cherokee graves. These graves were rectangular and contained European trade goods, like glass beads. This showed they were from the time when Native Americans traded with European settlers. However, there were no known major Cherokee villages on the island itself.

The Tellico Dam Project

In the 1930s, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was created. Its job was to build dams to make electricity and control floods. The TVA first planned to build Fort Loudoun Dam downstream from the Little Tennessee River's mouth. This would create a lake that would cover parts of both the Tennessee and Little Tennessee rivers. But engineers could not find a good spot for a dam there.

Instead, they built the dam about a mile (1.6 km) upstream. They planned to build another part at the mouth of the Little Tennessee. This was called the Fort Loudoun Extension. It would send water to the Fort Loudoun lake and help the dam make more power. But they didn't have enough money, so the project was put on hold until the 1960s.

The TVA became interested in the Fort Loudoun Extension again in 1964. They renamed it the Tellico Dam project. But many people were against it. These included environmental groups, people who wanted to save historical sites, and Native Americans. They all had different reasons for their opposition.

Construction of the dam started in 1969. But lawsuits stopped its completion until 1979. The University of Tennessee was hired to do many archaeological digs. They explored sites all over the Tellico Basin. Because of this work, several sites were added to the National Register of Historic Places. Bussell Island, known as 40LD17, was one of them.

Archaeological Digs

John W. Emmert's Work (1887)

John W. Emmert's digs for the American Bureau of Ethnology happened in 1887. His findings were written about in the bureau's 12th Annual Report in 1894. Emmert focused on two mounds on the north end of the island. They were called Mound 1 and Mound 2.

Mound 1 was 100 feet (30 m) across and 6.5 feet (2.0 m) high. Emmert found 14 skeletons there. He also found pottery pieces, flint chips, glass beads, and an iron bracelet. Mound 2 was a bit bigger than Mound 1. It had a diamond-shaped terrace next to it, which was 570 feet (170 m) long and 8 feet (2.4 m) high. Emmert thought this terrace was man-made. Diggers found 67 skeletons in Mound 2. They also found a burnt-clay mound surrounded by cedar posts.

Mark R. Harrington's Work (1919)

In 1919, Tennessee state archaeologist Mark Harrington traveled down the Tennessee River. He was looking at mounds along the river between Lenoir City and Hiwassee Island. Like Emmert, Harrington focused on the north end of Bussell Island. He noticed that the mounds Emmert had dug up were now flat.

Harrington found 41 burials. Nine of these belonged to the older "Round Grave" culture. He believed the rest were from the later Cherokee people. Harrington thought the large diamond-shaped terrace Emmert mentioned was actually a huge pile of ancient trash. This pile had built up over many centuries.

Harrington described the "Round Grave" burials as 2 to 3 feet (0.6 to 0.9 m) across. The bodies were folded to fit inside. Common items found with these burials included bone tools, steatite bowls, and animal teeth. In contrast, the Cherokee graves were rectangular. The bodies were laid in a bent position. Typical Cherokee burial items included pottery vessels, glass beads, and pipes.

See also

In Spanish: Isla Bussell para niños

In Spanish: Isla Bussell para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |