California agricultural strikes of 1933 facts for kids

The California agricultural strikes of 1933 were a series of worker protests. These strikes mainly involved Mexican and Filipino farm workers. They took place across the San Joaquin Valley in California.

More than 47,500 workers joined about 30 strikes between 1931 and 1941. The Cannery and Agricultural Workers' Industrial Union (CAWIU) led 24 of these strikes. These involved 37,500 union members. The strikes are grouped because CAWIU organized most of them.

The protests began in August among workers picking cherries, grapes, peaches, pears, sugar beets, and tomatoes. They became biggest in October with strikes against cotton growers in the San Joaquin Valley. The cotton strikes involved the most workers. Some reports say 18,000 workers joined. Others say 12,000, with 80% being Mexican.

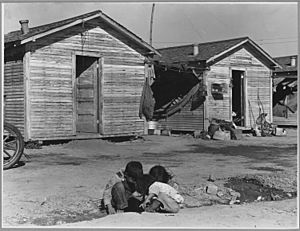

During the 1933 cotton strikes, workers were forced out of their company homes. Farm owners and managers were made special police officers by local law enforcement. Attacks on peaceful striking workers were common. Local bankers, merchants, ministers, and even Boy Scouts encouraged these attacks.

A sheriff once said, "We protect our farmers here. But the Mexicans are trash. They have no good way of life." In Pixley, California, two strikers, Dolores Hernàndez and Delfino D'Ávila, were killed. Eight others were hurt. This happened after local sheriffs gave out 600 permits for people to carry hidden weapons. Eight farm owners were charged in the shootings, but all were found not guilty.

Another worker, Pedro Subia, was killed near Arvin, California. Workers from camps around Bakersfield gathered to remember him. They met at Bakersfield City Hall. CAWIU organizers Pat Chambers and Caroline Decker were arrested. They were charged under the California Criminal Syndicalism Act for their organizing work. This act made it illegal to promote certain political changes.

Contents

Why Workers Went on Strike

Cotton growers in the San Joaquin Valley became top producers in the country. They grew more cotton per acre than the Old South. This was because they paid very low wages to workers. Even though California cotton growers paid a little more than those in other states, wages had dropped a lot.

In 1928, workers earned $1.50 for every hundred pounds of cotton picked. By 1932, this fell to just 40 cents. Sometimes the rate could go up to 60 cents. This higher rate was for ground picked a second or third time. The Agricultural Labor Bureau, a group of employers, set these wages.

The Great Depression started in 1929. This lowered the demand for cotton. Many small farmers lost their land to banks like Bank of America. In 1933, the U.S. government helped the growers with money. This was called a subsidy or bailout. Workers hoped the growers would share this money with them. But this did not happen, which led to the strike.

The Cannery and Agricultural Workers' Industrial Union (CAWIU) was a workers' organization. It had been organizing in the cotton fields for some time. By 1933, it became the main leader for the cotton pickers. Most of these workers were Mexican.

The CAWIU made strong demands. They threatened a strike across the entire valley if their demands were not met. They wanted $1.00 for every hundred pounds of cotton picked. They also wanted the CAWIU to be recognized as the workers' official voice. They also wanted to end "contract labor." This was when a large group of workers was hired for a short time.

These demands were made in almost every cotton strike in 1933. On September 18, a group of 78 men and women organized the cotton strikes. They figured it took a worker 10 hours to pick 300 pounds. Growers offered 40 cents per hundred pounds. This was not enough for food and gas to get to the next job. So, workers demanded a dollar per hundred pounds. Growers later offered 60 cents due to public pressure. But this was still not enough, so the strike began.

The Cotton Strikes of October 1933

The cotton strikes started on October 4, 1933. Workers set up picket lines at their workplaces. At one ranch, workers wore signs saying "This ranch under strike." They organized shifts to picket 24 hours a day. Women played a key role in organizing the strike. They used their social networks to share information across worker camps. This helped them decide when and where to strike.

The Los Angeles Times reported the reason for the strikes. Workers wanted a 40-cent increase per hundred pounds. This was above the 60-cent rate set by the San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Bureau. Cotton growers in Kern County had agreed to this lower rate.

When growers first heard about the strike, they reacted strongly. Seventy-five growers in Kings County gave pickers and their families five minutes to pack. They then dumped their belongings on the highway. The Kings County District Attorney said, "The sheriff and I told the growers not to worry about the pickers' rights anyway."

Luckily, the Cannery and Agricultural Workers' Industrial Union had rented camp spaces. These were close to the cotton-picking areas. The most important camp was in Corcoran, California. The people in Corcoran barely tolerated the Mexican workers. It was hard for workers to get basic things like health care.

On the first day of the strike, a California Highway Patrol vehicle drove through Corcoran. It had a machine gun mounted on it. A witness, Rudy Castro, said they were ready to shoot the strikers. This was just because the workers asked for more money. There were almost 3,800 strikers at the Corcoran camp. The workers outnumbered the townspeople almost two to one. A tent school was set up at the camp for about 70 children. Lino Sànchez, a Corcoran resident, led nightly meetings in another part of the camp.

Three days into the protests, cotton growers worried their crop would not be picked at its best value. They also feared angry workers might damage their crops. They worried about harm to workers who did not strike. Two days later, the strike became violent. Workers were forced out of company housing.

In Tulare County, armed men hired by growers fought with striking workers. CAWIU organizers were forced out of the county. Growers in Kings, Fresno, Madera, Merced, Stanislaus, and San Luis Obispo counties armed themselves and their employees. They announced they would drive away any "troublemakers." In Kern County, about 200 strikers and their families were evicted from their employer-owned homes. Their belongings were left on the road. They were told to leave the county or face trouble.

Tensions reached a high point on October 10 in Pixley. About 30 ranchers surrounded a meeting of striking workers. The ranchers fired at the strikers, killing three and wounding others. That same day, striking grape pickers faced armed growers' men. This happened at a farm near Arvin, California, about 60 miles (97 km) south of Pixley. After hours of facing each other, the two sides began fighting. Workers used wooden poles, while the growers' men used their rifle butts. A shot was fired, and a striking worker, Pedro Subia, was killed. A sheriff's deputy threw a tear gas grenade. The growers' men then opened fire. Several strikers were wounded.

Ending the Cotton Strikes

The cotton strikes ended in late October. The killings in Pixley and Arvin led to public anger against the growers. The California Highway Patrol sent many officers to the area to restore order. Federal and state officials arrived to help end the strikes. Government welfare and public works officials also came. They wanted to see how to fix the economic problems causing the strikes.

Angry workers wanted to fight back against the growers. But CAWIU leaders stopped them. Public opinion now strongly supported the strikers. California Governor James Rolph agreed to meet with union leaders. He heard their demands. Governor Rolph did not send more police or disarm the growers. But he did announce that the State Emergency Relief Administration would use federal money. This money would help striking workers.

George Creel, who led the Regional Labor Board, stepped in. This board was part of the National Labor Board, a federal agency for worker relations. Creel began to actively help settle the strikes. He did not have official power, but his confidence impressed both growers and workers. He warned growers that the Roosevelt administration would stop federal farm help to California if the violence continued. He suggested a three-person group to find facts and settle the strike. The growers agreed.

Creel told the growers that workers would return to work for 60 cents per hundred pounds while the group did its work. So, the federal and state governments tried to get workers back to work on October 14. This effort failed. State officials said workers would only get relief payments if they returned to work. But striking workers refused. The state then started giving payments again without conditions on October 21.

The fact-finding group held its meetings on October 19 and 20. Creel pushed the group. On October 23, they announced that growers should offer 75 cents per hundred pounds. The growers accepted this on October 25. CAWIU asked for 80 cents per hundred and for the union to be recognized. But Creel said all relief payments would stop if workers did not agree to the group's rate.

Workers seemed to want to continue the strikes. But CAWIU leaders agreed to the group's solution on October 26. They called an end to all cotton strikes happening in California.

See also

In Spanish: Huelgas agrícolas de California de 1933 para niños

In Spanish: Huelgas agrícolas de California de 1933 para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |