Camp Douglas (Chicago) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Camp Douglas |

|

|---|---|

| Chicago, Illinois, US | |

Union soldier training camp and the largest prisoner of war camp for detaining military personnel of the Confederate States of America

|

|

| Type | Training Camp and Union Prison Camp |

| Site information | |

| Owner | U.S. Government |

| Controlled by | Union Army |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1861 |

| In use | 1861–1865 |

| Demolished | 1865 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders |

Brigadier General Daniel Tyler

Brigadier General Jacob Ammen Brigadier General William W. Orme Colonel Joseph H. Tucker Colonel Arno Voss Colonel James A. Mulligan Colonel Daniel Cameron Colonel Charles V. DeLand Colonel James C. Strong Colonel Benjamin J. Sweet Captain J. S. Putnam |

| Occupants | Union soldiers, Confederate prisoners of war |

Camp Douglas was a very important place in Chicago, Illinois, during the American Civil War. It was one of the biggest Union Army camps for holding Confederate soldiers who were captured. It was also used as a training camp for Union soldiers.

The Union Army first used Camp Douglas in 1861 to organize and train new volunteer soldiers. Then, in early 1862, it became a prison camp for captured Confederates. Later in 1862, it was used again for training. In the fall of 1862, it even held Union soldiers who had been captured by the Confederates and then released under a special agreement, waiting to be officially exchanged.

Camp Douglas became a permanent prisoner-of-war camp from January 1863 until the war ended in May 1865. After the war, in the summer and fall of 1865, it was used to send Union Army volunteers home. The camp was then taken apart, and the land was sold and developed.

After the war, Camp Douglas became known for its tough conditions and a high death rate. About 4,275 Confederate prisoners who died at the camp were later moved from the camp cemetery to a large grave at Oak Woods Cemetery.

Contents

Building Camp Douglas

Choosing the Location

When the Civil War began in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln asked for many volunteers to join the army. Thousands of volunteers from Illinois gathered in Chicago. They first stayed in buildings and then set up makeshift camps on the prairie south of the city.

Senator Stephen A. Douglas owned land nearby and had given some land just south of these camps to the Old University of Chicago. The state of Illinois chose this area for a permanent army camp because it was close to downtown Chicago, surrounded by open land, near Lake Michigan for water, and had a railroad line nearby.

However, the person who chose the site didn't realize it was a bad choice. The land was low and wet, and it flooded easily when it rained. For over a year, the camp didn't have proper sewers, and waste from thousands of people and horses made the ground very dirty. In winter, it was a sea of mud. There was also a big shortage of toilets and medical help.

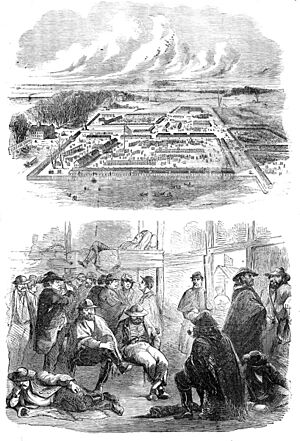

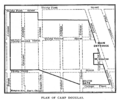

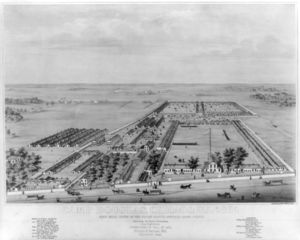

Camp Layout

The camp stretched about four blocks west from Cottage Grove Avenue. Its northern edge was near what is now East 31st Street, and its southern edge was near East 33rd Place. A gate on the south side led to land donated by Senator Douglas, where a smallpox hospital, barracks, and a railroad station were built.

The camp changed over time, but it had main areas. "Garrison Square" had officers' living areas, the main office, a post office, and a parade ground. "White Oak Square" housed both Union soldiers and prisoners. It had the first prison and a small, dark room called the "White Oak Dungeon" where prisoners were punished. This room was very small and dirty, with poor air.

Later, "Prison Square" was built in the western part of the camp. It had 64 barracks, each designed for about 95 men, but often held about 189 men when the prison was full.

Building the Camp

Colonel Joseph H. Tucker was put in charge of building and commanding the camp. Carpenters from the state militia built the barracks in late 1861. These workers had a disagreement with the state about their pay and caused some trouble before being allowed to go home.

By November 1861, Camp Douglas held about 4,222 Union volunteer soldiers. By February 1862, 42 recruits had died from disease. About 40,000 Union Army recruits passed through the camp for training before it became a permanent prison. Colonel Tucker had a tough job keeping order among the recruits.

Becoming a Prisoner of War Camp (1862)

First Prisoners Arrive

In February 1862, the Union Army captured Fort Donelson and Fort Henry, taking about 12,000 to 15,000 Confederate prisoners. The army wasn't ready for so many prisoners and looked for places to hold them. Colonel Tucker said Camp Douglas could hold 8,000 or 9,000 prisoners.

About 4,459 of these prisoners were sent to Camp Douglas. On February 20, 1862, the first prisoners arrived. They found a camp, but not a real prison. For the first few days, they stayed in the White Oak Square section with Union soldiers. Many sick prisoners were sent to the camp, even though it had no medical facilities.

On February 23, 1862, most Union troops left, leaving only a small guard force. A few days later, Confederate officers were moved to another camp, making Camp Douglas a prison only for enlisted men. In just over a month, by the end of March, more than 700 prisoners had died. About 77 prisoners escaped by June 1862.

Colonel James A. Mulligan in Command

Colonel James A. Mulligan took command of the camp in late February 1862. At first, prisoners were treated fairly well, considering the poor state of the camp. They received enough food, cooking supplies, and clothing.

However, sickness and death became very common among prisoners and even some guards. Frozen water pipes caused water shortages. One out of eight prisoners from Fort Donelson died from pneumonia or other diseases. Colonel Mulligan later allowed only doctors and ministers to visit prisoners to help stop the spread of illness.

Colonel Mulligan worked with local people who formed a relief committee to help the prisoners after they heard about the bad conditions.

After Union victories in the spring of 1862, Camp Douglas held 8,962 Confederate prisoners. Conditions got worse due to overcrowding, and more prisoners escaped. Some escapes were helped by Southern supporters in Chicago.

Improving Conditions (Slowly)

To manage the large number of prisoners, the Army created the Office of the Commissary-General of Prisoners in June 1862. Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman took over this office in August 1862 and set rules for all prison camps.

Colonel Hoffman quickly saw that Camp Douglas was not good enough for a prison. He suggested building better barracks, but the Army only approved simple, single-story buildings. Commanders tried to get money for better sewers and new barracks, but it was hard. It wasn't until June 1863 that a new sewer system was approved.

Some historians have said that commanders didn't provide a good enough diet for the prisoners, which could have prevented diseases like scurvy (caused by lack of vitamins).

Colonel Joseph H. Tucker's Second Command

Colonel Tucker returned to command the camp in June 1862. To stop local people from helping prisoners escape, he declared a special rule on July 12, 1862, that allowed the military to take over some civilian functions. When 25 prisoners escaped, Tucker arrested some citizens he thought had helped. He also brought in Chicago police to search the camp, and they took many valuables from the prisoners.

Conditions improved that summer as almost all prisoners left by September 1862. About a thousand prisoners promised loyalty to the United States and were set free. Other prisoners were exchanged with the Confederate army. By October 1862, nearly all prisoners were gone. By this time, 980 Confederate prisoners and 240 Union soldiers and guards had died at Camp Douglas, mostly from disease.

Training Camp and Union Parolee Camp (1862)

In the fall of 1862, Camp Douglas briefly became a training camp again for Union Army volunteers. Then, it was used for a very unusual purpose.

Union Soldiers Held at Camp Douglas

Union soldiers who were captured by Confederate General Stonewall Jackson in September 1862 were sent to Camp Douglas. Under the prisoner exchange rules, they had to stay there until they were officially exchanged. About 8,000 of these Union soldiers arrived at Camp Douglas starting September 28, 1862. Brigadier General Daniel Tyler took command of the camp.

These Union soldiers had to live in conditions similar to what the Confederate prisoners had faced. The camp was even dirtier and more run down. The Union soldiers were lucky to stay for only about two months. They were also better dressed and in better physical shape than the previous prisoners. Still, the damp conditions and bad food caused sickness.

The Union soldiers became restless, started fires, and tried to escape. General Tyler brought in regular U.S. troops to stop the unrest. The Secretary of War told Tyler to ease up on his strict rules, which helped calm the soldiers. Most of these Union soldiers left by the end of November 1862.

Prison Camp (1863–1865)

New Prisoners and Harsh Winter

In January 1863, new Confederate prisoners from the Battle of Stones River and Arkansas Post were sent to Camp Douglas. About 1,500 arrived on January 26, 1863, and thousands more followed. Many of these prisoners were sick and poorly clothed. The Army didn't make immediate improvements to the camp.

During February 1863, 387 out of 3,884 prisoners died. This was the highest death rate for any Civil War prison camp in one month. Temperatures were very low, sometimes −20 °F (−29 °C). Smallpox and other diseases spread quickly. By March 1863, many prisoners and guards had died from smallpox.

By April 1863, about 784 prisoners from this group had died. Many deaths were caused by typhoid fever and pneumonia. The prisoners arrived weak and then suffered from dirty conditions, a poor sewer system, very cold weather, and not enough heat or clothing.

Improvements and More Prisoners

In the summer of 1863, the army made some improvements to the camp, planning to use it for training new Union recruits again. However, Union victories led to many new prisoners, so Camp Douglas became a POW camp again until the end of the war.

The first new prisoners, 558 guerrilla fighters led by Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan, arrived in August 1863. Colonel Charles V. DeLand took command. By September 1863, Camp Douglas held 4,234 Confederate prisoners, and by October, that number rose to 6,085.

Conditions were still difficult. There were only two water spouts for prisoners, so they waited hours for water. Open sewers ran through the camp, and buildings were in bad shape. Hospitals were too small for all the sick.

Colonel DeLand tried to improve things. He had prisoners build a new sewer system (they were paid in tobacco and clothing). He also had them build a stronger fence. He provided cooking tools and cleaning supplies. The new sewers were finished by November 1863, but they were still not perfect. Floors were put back in barracks, and buildings were raised off the ground, which helped with cleanliness and prevented tunneling.

However, discipline became very strict. Prisoners who tried to escape were put in the "White Oak Dungeon," a tiny, foul-smelling room. More than 150 prisoners escaped during DeLand's time in command.

There were also problems with food quality. Some suppliers gave poor quality meat to the camp.

General William W. Orme Takes Command

In December 1863, Brigadier General William W. Orme took over as commander. He tried to fix the food problems and other issues. He also got more guards for the camp.

A severe blizzard hit in January 1864. General Orme managed to get some Union army overcoats and gave them to prisoners, even though it was against the rules.

An inspection in January 1864 found the barracks still very dirty, muddy, and full of bugs because there were no floors. Cooking was poor, and garbage was everywhere. Old sewers were leaking. The hospital was good, but it was full, and 250 sick men had to stay in the barracks. Thirty-six percent of prisoners were sick, and 57 had died in December 1863. The guards also suffered from the bad conditions. The inspector said the camp was not fit for use, but it remained open.

Prisoners were moved to a new "Prisoner's Square" area. Floors were put back in all barracks by February 1864, and the buildings were raised off the ground. This helped with cleanliness and made it harder to dig tunnels. More water spouts were added, and fences were completed. Bright lamps were put on the fences to light the area at night.

A new hospital with modern features was built in April 1864, but it was still too small. Strict discipline and harsh treatment of prisoners increased.

In April 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant stopped all prisoner exchanges. This meant both Union and Confederate armies had to hold many more prisoners for longer periods.

Colonel Benjamin J. Sweet in Command

In May 1864, Colonel Benjamin J. Sweet became the camp commander. He was known as a very strict leader. He increased punishments and cut food portions, following new War Department rules. He was a better organizer than previous commanders.

Sweet made changes to the food, removing some items he thought were wasted. He used forced labor to build new barracks and organized them into parallel streets. Guards searched prisoners daily for hidden money that could be used for bribes.

The ground in the camp became very dusty. Sweet ordered more toilets built and pine boards delivered for repairs. He also tried to make prisoners keep the camp clean.

As more prisoners arrived in the summer of 1864, the War Department cut food rations again. Some prisoners reported eating rats because food was so scarce. Guards punished prisoners caught taking bones from the garbage. Fights between prisoners also increased.

Guards also used a device called "the mule" or "wooden horse" as punishment. Prisoners were forced to sit on a thin, sharp edge, sometimes with weights tied to their feet, in any weather.

The 1864 'Camp Douglas Conspiracy'

In November 1864, there was a supposed plot to attack Camp Douglas and free the prisoners. Historians still debate if this plot was real or if it was made up by people trying to gain something.

In the spring of 1864, Confederate agents were sent to Canada to plan prison escapes and attacks in the North. One agent, Captain Thomas Hines, believed he could gather about 5,000 Confederate supporters in Chicago to free the prisoners. However, there's little proof of detailed planning before August 1864, and he only found 25 volunteers.

Colonel Sweet, the camp commander, kept the idea of the plot alive, telling his superiors he was about to stop a dangerous uprising.

On November 6, 1864, Colonel Sweet was allowed to arrest two Confederate agents in Chicago. Sweet claimed that Confederate officers were in town planning to release the prisoners. Without a warrant, Sweet's men searched the home of Charles Walsh, a leader of a group called the "Sons of Liberty," who were sympathetic to the South. They found some guns and ammunition, but not enough to arm 2,000 men as the plot supposedly required.

Sweet arrested 106 men, including Walsh and a judge. Over half of them were quickly released. Sweet claimed to have stopped a big plot. The Secretary of War approved Sweet's actions, and he received more troops.

Sweet's main informer was a Confederate prisoner who testified against the arrested people. Many were convicted. President Lincoln promoted Sweet to a higher rank for his actions.

Final Months (1864-1865)

Late 1864 and 1865

By late 1864, doctors refused to send recovering prisoners back to the barracks because of widespread scurvy, a disease caused by lack of vegetables. In October 1864, 984 out of 7,402 prisoners were reported sick. In November 1864, water was cut off to the camp and even the hospital. Prisoners had to risk being shot to gather snow for water.

In December 1864, new prisoners from Confederate General John Bell Hood's army arrived. These prisoners were weak and had their belongings taken by guards. Food rations were just enough to keep men "tolerably hungry."

New, larger water pipes helped the toilets work better. With bathing and laundry facilities available, prisoners themselves made sure others washed their clothes and bathed. Mail was sent and delivered regularly, even to prisoners in the dungeon. While conditions were harsh, there is little evidence that prisoners "often" froze to death, though some sick prisoners likely died from the cold.

Many dead prisoners were first buried in unmarked graves in Chicago's City Cemetery. In 1867, their bodies were moved to what is now called Confederate Mound in Oak Woods Cemetery, about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the old Camp Douglas site.

End of the War

When Robert E. Lee's army surrendered in April 1865, the war was almost over. On May 8, 1865, Colonel Sweet received orders to release all prisoners except high-ranking officers. Those who promised loyalty to the United States were given transportation home. About 1,770 prisoners refused to take the oath.

On July 5, 1865, the guards left the camp. Only 16 prisoners remained in the camp hospital. Colonel Sweet resigned from the army in September 1865. About 26,060 Confederate soldiers had passed through Camp Douglas by the end of the war.

After the war, the camp was closed. The barracks and other buildings were taken down by the end of November 1865. The land was sold or returned to its owners.

Aftermath

Deaths at Camp Douglas

The official number of Confederate prisoners who died at Camp Douglas is about 4,454. The worst time for deaths was in 1865, when 867 prisoners died before the war ended and the remaining prisoners were released.

After the war, Camp Douglas was sometimes called the "Andersonville of the North" because of its poor conditions and high number of deaths. Camp Douglas was one of the longest-running and largest prisons in the North. While many prisoners died there, the percentage of deaths was similar to most other Union prisoner of war camps. The death rate at Camp Douglas was actually lower than at Andersonville, a famous Confederate prison. If any Northern camp was like Andersonville, it would be Elmira Prison in New York, which had a much higher death rate.

Camp Douglas Today

Today, most of the land where Camp Douglas stood is covered by modern buildings like condominiums. For many years, a local funeral home on the site kept prisoner records and flew a Confederate flag at half-staff. The business closed in 2007.

Since 2012, archaeological digs have been happening at the site with the help of college students and local volunteers. A group called the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation, started in 2010, hopes to create a permanent museum on the site to tell its story.

Images for kids

-

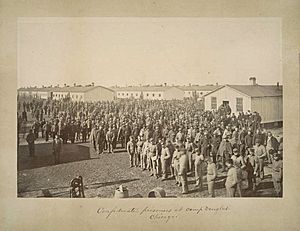

Union soldier training camp and the largest prisoner of war camp for detaining military personnel of the Confederate States of America

-

Union prisoner of war camp in Chicago during the American Civil War

-

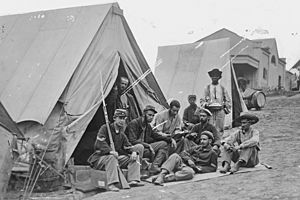

Five unidentified prisoners of war in Confederate uniforms in front of their barracks at Camp Douglas Prison. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs

-

Oak Woods Cemetery, Chicago

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |