Joseph H. Tucker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph H. Tucker

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1819 New York |

| Died | October 22, 1894 (aged 74–75) New York City |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

Illinois militia |

| Years of service | 1861–1862 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Other work | Businessman, stockbroker |

| Signature | |

Joseph H. Tucker (1819 – October 22, 1894) was a successful businessman and a military leader from Illinois. He served as a colonel in the Illinois militia during the first two years of the American Civil War. Colonel Tucker was given the important job of building Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois. He was also the first person in charge of this camp.

Camp Douglas started as a training place for new soldiers joining the Union Army. Later, in 1862 and 1863, it became a prison camp for soldiers from the Confederate States Army who were captured by the Union Army. Colonel Tucker led the camp from when it started in October 1861 until September 28, 1862. During this time, the camp was used for both training and holding prisoners of war. Joseph Tucker was never officially part of the Union Army; he remained a colonel in the Illinois militia throughout his service in the Civil War.

Contents

Early Life and Business

Joseph H. Tucker was born in New York in 1819. His father was a Baptist minister. Before moving to Chicago, Illinois, in 1858, Tucker worked as a banker and businessman in Cumberland, Maryland. He was very good at business, banking, and trading stocks.

Service During the Civil War

Why Camps Were Needed

The Civil War began on April 15, 1861, after Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter. The very next day, President Abraham Lincoln asked for 75,000 state militia members to join the fight for ninety days. He asked for more volunteers later in May 1861. The U.S. Congress then agreed to Lincoln's actions and allowed for one million more volunteers to serve for three years.

At first, each state and local area had to organize and equip their own volunteer groups. This continued until the federal government was ready to take over later in 1861. Many volunteers from Illinois gathered in Chicago. They filled public buildings and then set up makeshift camps on the edge of the city. Senator Stephen A. Douglas owned land nearby and gave some of it to the original University of Chicago.

Building Camp Douglas: Tucker's First Command

Illinois Governor Richard Yates chose a judge named Allen C. Fuller to pick the best spot for a permanent army camp in Chicago. Judge Fuller picked the area where the temporary camps already were. This spot was good because it was close to downtown Chicago, had open land around it, could get water from nearby Lake Michigan, and was near the Illinois Central Railroad.

However, Judge Fuller was not an engineer. He did not realize that the low, wet ground was a poor choice for a large camp. When the camp first opened, it did not have enough medical facilities, sewers, toilets, or proper drainage. It also had only one water faucet.

Governor Yates put Colonel Joseph H. Tucker in charge of building Camp Douglas. He also made Tucker the camp's first commander. State militia troops, who were skilled carpenters, built the barracks in October and November 1861. There were some problems, like construction workers rioting when the state tried to change their roles and not pay them extra as promised. Colonel Tucker had to deal with these issues.

By November 15, 1861, Camp Douglas held about 4,222 volunteer soldiers. Even these healthy recruits suffered. Forty-two of them died from disease by February 1862. This showed how difficult conditions were at the camp, even before it became a prison.

On February 16, 1862, the Union Army, led by Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, captured Fort Donelson in Tennessee. They took about 12,000 to 15,000 Confederate soldiers as prisoners. The army was not ready for so many prisoners. Colonel Tucker told Major General Henry Halleck, Grant's superior, that Camp Douglas could hold 8,000 or 9,000 prisoners. However, the camp and its staff struggled to handle even the 4,459 prisoners who were sent there.

The first Confederate prisoners arrived at Camp Douglas on February 20, 1862. They found a camp, but not a proper prison. For their first few days, they stayed in the same area as newly trained Union soldiers. The army also sent sick prisoners to the camp, even though there were no medical facilities at the time. On February 23, 1862, most Union troops left the camp, leaving only a small guard force. About 77 prisoners escaped from Camp Douglas by June 1862.

On February 26, 1862, General Halleck ordered Colonel Tucker to report to Springfield, Illinois. Another Union Army officer, Colonel James A. Mulligan, took command of the camp until June 14, 1862. Colonel Daniel Cameron, Jr. was in charge for a few days after that.

Colonel Mulligan's Time in Command

The first group of prisoners was treated fairly well, considering the poor conditions of the camp's grounds, barracks, and water systems. They received enough food, cooking supplies, and clothing. However, many prisoners, and even some guards, became very sick and died. Frozen water pipes caused a water shortage. One out of every eight prisoners from Fort Donelson died from pneumonia or other diseases.

After the Union Army won the battle of Shiloh and captured Island No. 10 in the spring of 1862, Camp Douglas held 8,962 Confederate prisoners. The camp became even more crowded, and conditions got worse. More prisoners escaped. Some escapes were helped by people in Chicago who supported the South. Others happened because Colonel Mulligan and the guards were not strict enough.

Tucker's Second Command

Even though he was still in the Illinois militia, Colonel Tucker returned to command Camp Douglas on June 19, 1862. To stop local people from helping prisoners escape, Colonel Tucker declared martial law on July 12, 1862. This meant military rules were in effect. When twenty-five prisoners escaped on July 23, 1862, Tucker arrested several citizens he believed had helped them. He also brought in Chicago police to search the camp. This made the prisoners very angry because the police took many of their valuable items. The police also found five pistols and many bullets. Twenty of the escaped prisoners were caught again within two weeks.

In the summer of 1862, Henry Whitney Bellows, who led the U.S. Sanitary Commission, visited the camp. He wrote to Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman, who was in charge of Union prison camps. Bellows said the camp was in terrible condition with standing water, dirty grounds, bad toilets, crowded barracks, and a lot of filth. He believed the camp was so unhealthy that it should be completely abandoned. He thought only fire could truly clean it. Hoffman had already asked for improvements, but he kept Bellows' report a secret. He did not want to disagree with his superiors who opposed spending money on the camp. The camp was so unhealthy that one of Colonel Tucker's sons, Captain Lansing Tucker, who served with him at the camp, became ill and died in the summer of 1862.

Conditions at the camp got better that summer as almost all the prisoners left by September 1862. About one thousand prisoners promised loyalty to the United States and were set free. All prisoners who were healthy enough to travel were exchanged. This happened because of an agreement between the Union and Confederate armies called the Dix–Hill prisoner cartel. By October 6, 1862, the few remaining prisoners who had been too sick to leave earlier were also gone. By September 1862, 980 Confederate prisoners and 240 Union Army trainees and guards had died at Camp Douglas. Almost all of these deaths were from disease.

In the fall of 1862, Camp Douglas briefly became a training camp for Union Army volunteers again. Then, the Union Army used the camp for a very unusual purpose.

End of Tucker's Service

Union soldiers who were captured by Confederate Lieutenant General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson at the Battle of Harpers Ferry on September 15, 1862, were sent to Camp Douglas. These soldiers were "paroled," meaning they promised not to fight again until they were officially exchanged for Confederate prisoners. They had to wait at the camp until this exchange happened.

About 8,000 paroled Union soldiers began arriving at Camp Douglas on September 28, 1862. Brigadier General Daniel Tyler took over command of the camp from Colonel Tucker. These Union soldiers had to live in conditions similar to those the Confederate prisoners had faced. In fact, the conditions were worse because the camp had become very dirty and run down. The paroled soldiers were lucky that their stay was only about two months. They handled the conditions a bit better than the Confederate prisoners because they were dressed more warmly and were in better physical shape. Still, the dampness and bad food made many sick. By November, forty soldiers from the 126th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment had died, and about sixty more were ill with fevers. Soon after Tucker left the Illinois militia, Brigadier General Jacob Ammen became the camp commander.

Later Life

Joseph H. Tucker lost two of his sons during the war. He left Chicago in 1865 and never returned. He continued his career as a businessman and was a member of the New York and Consolidated Stock Exchanges in New York City. He became ill and unable to work by 1887.

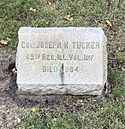

Joseph H. Tucker died in New York City on October 22, 1894, when he was 74 or 75 years old. He was buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |