Camp Grant massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Camp Grant Massacre |

|

|---|---|

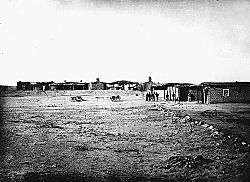

Camp Grant, photographed by John Karl Hillers in 1870 |

|

| Location | near Camp Grant, Arizona Territory |

| Date | April 30, 1871 |

| Attack type | Mass murder |

| Deaths | 144 |

| Perpetrator | O'odham warriors, Mexican and American civilians |

The Camp Grant massacre happened on April 30, 1871. It was a surprise attack on Pinal and Aravaipa Apaches who had given up to the United States Army at Camp Grant, in Arizona. This camp was located along the San Pedro River.

This terrible event led to many more fights between the Americans, the Apache people, and their Yavapai allies. These conflicts continued until 1875. One of the most well-known of these was General George Crook's Tonto Basin Campaign in 1872 and 1873.

Contents

Why Did the Camp Grant Massacre Happen?

Some historians believe that when there was less fighting with Native American groups, people in Tucson worried about their money. The government was spending less on keeping peace with tribes like the Apaches. Businesses that made money from these peace efforts feared they would lose their income.

In early 1871, some people in Arizona supposedly faked attacks on small towns. They did this to get more public support for fighting and to get more money from the government to give "gifts" to the Apaches. One of these towns was in Aravaipa Canyon.

During the early 1870s, the situation with Native Americans in Arizona kept changing between peace and war. Each new fight caused more problems between the settlers and the soldiers. A group called the Board of Indian Commissioners was created in 1869 to look into problems within the government's Native American affairs office. This group helped start a movement for Native American rights, which was supported by President Ulysses S. Grant.

A big challenge for the military in Arizona was that they had too few soldiers for such a huge area. Many people at the time thought Apaches were the biggest threat. However, Yavapai people, who spoke a different language and were sometimes called Apache Mohaves, also attacked settlers often. The Yavapais lived across a large area, from the Colorado River to the Tonto Basin. Like the Apaches, they moved around a lot and were very independent. They only had war chiefs and advisors chosen by local groups. This made it very hard for the U.S. Army to catch or talk with more than one Yavapai group at a time. Soldiers had to chase the Yavapais across rough desert terrain. Many soldiers even ran away from places like Camp Grant, which was a hot, dusty collection of adobe buildings.

Camp Grant's Role in the Peace Efforts

In early 1871, a 37-year-old first lieutenant named Royal Emerson Whitman took charge of Camp Grant, Arizona Territory. This camp was about 50 miles (80 km) northeast of Tucson. In February 1871, five older Apache women came to Camp Grant looking for a son who had been captured. Whitman was kind to them and gave them food. Because of this, other Apaches from the Aravaipa and Pinal groups soon came to the camp to get food like beef and flour.

That spring, Whitman created a safe place for nearly 500 Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches, including their Chief Eskiminzin. This refuge was along Aravaipa Creek, about five miles (8 km) east of Camp Grant. The Apaches started cutting hay for the camp's horses and harvesting barley in nearby farms.

Whitman might have worried that this peace would not last. He asked Eskiminzin to move his people to the White Mountains near Fort Apache, which was built in 1870, but Eskiminzin said no. During the winter and spring, two men, William S. Oury and Jesús María Elías, formed a group called the Committee of Public Safety. This group blamed every attack in southern Arizona on the Camp Grant Apaches. After Apaches took livestock from San Xavier on April 10, Elías contacted his friend Francisco Galerita, who was the leader of the Tohono O'odham people at San Xavier. Oury also gathered weapons and ammunition from his supporters.

The Attack Itself

On the afternoon of April 28, six Anglo Americans, 48 Mexican Americans, and 92 Tohono O'odham people gathered near Rillito Creek. They then marched towards Aravaipa Canyon. William S. Oury, one of the Americans, was the brother of Granville Henderson Oury.

At dawn on Sunday, April 30, they surrounded the Apache camp. The O'odham people did most of the fighting, while the Americans and Mexicans shot at Apaches who tried to run away. Most of the Apache men were away hunting in the mountains. All but eight of the people killed were women and children. Twenty-nine children were captured and sold into slavery in Mexico by the Tohono O'odham and the Mexicans. In total, 144 Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches were killed.

What Happened Next?

Lieutenant Whitman looked for wounded people and found only one woman. He buried the bodies and sent interpreters into the mountains to find the Apache men. He wanted to assure them that his soldiers had not been part of the "vile transaction" (the massacre). The next evening, the surviving Aravaipa Apaches slowly started to return to Camp Grant.

Many settlers in southern Arizona thought the attack was justified and agreed with Oury. However, this was not the end of the story.

Within a week of the killings, a local businessman named William Hopkins Tonge wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He stated, "The Indians at the time of the massacre being so taken by surprise and considering themselves perfectly safe with scarcely any arms, those that could get away ran for the mountains." He was the first person to call what happened a massacre.

The military and newspapers in the Eastern part of the country also called it a massacre. President Grant told Governor A.P.K. Safford that if the people who did this were not put on trial, he would place Arizona under martial law (military rule).

In October 1871, a grand jury in Tucson accused 100 of the attackers of 108 counts of murder. The trial, two months later, focused only on past Apache attacks. It took the jury just 19 minutes to say the attackers were not guilty.

Because of fear of more attacks, Western Apache groups soon left their farms and gathering places near Tucson. As pioneer families moved into the area, Apaches were never able to get back much of their traditional lands in the San Pedro River Valley. Many Apache groups joined with the Yavapais in Tonto Basin. From there, a guerilla war (a type of fighting where small groups use surprise attacks) began, which lasted until 1875.

Where Was the Camp Grant Massacre Site?

The massacre happened near Camp Grant. In 1871, Camp Grant was located on a high area on the east side of the San Pedro River, just north of where it met Aravaipa Creek. The camp was around 32°50'51.22"N, 110°42'11.91"W.

The Camp Grant site was near what is now the Aravaipa Campus of Central Arizona Community College. This college is between the towns of Mammoth and Winkelman on Arizona State Route 77. Not much is left of the original camp site today.

Experts today believe the actual massacre site was south of Aravaipa Creek and about five miles upstream from Camp Grant. There is no marker at the massacre site, and its exact location is only generally known.

In 2021, descendants of those who were killed in the massacre were fighting against a very large copper mine being built at Oak Flat, which is close to the massacre site.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |