Caroline Shawk Brooks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

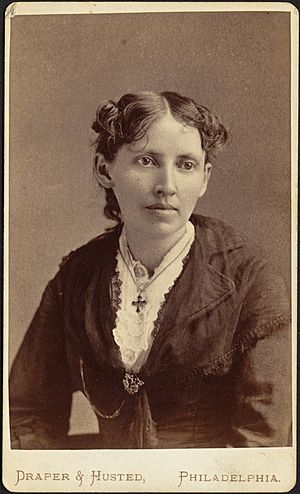

Caroline Shawk Brooks

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Caroline Shawk

April 28, 1840 Cincinnati, Ohio

|

| Died | 1913 (aged 72–73) St. Louis, Missouri

|

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture |

|

Notable work

|

Dreaming Iolanthe |

| Spouse(s) | Samuel H. Brooks |

Caroline Shawk Brooks (born April 28, 1840 – died 1913) was an amazing American sculptor. She became famous for her unique art: sculpting with butter! But she also created beautiful works using traditional materials like marble.

Contents

Early Life of Caroline Shawk Brooks

Caroline Shawk was born on April 28, 1840, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her father, Abel Shawk, built fire engines and steam locomotives. He even invented the first successful steam-powered fire engine. From a young age, Caroline loved art. She enjoyed painting and drawing. Her very first sculpture was Dante's head, which she made from clay found in a creek.

When she was twelve, Caroline won a medal for her wax flowers. She graduated from the St. Louis Normal School in 1862. Later that year, she married Samuel H. Brooks, who worked for the railroad. The couple first lived in Memphis, Tennessee. Then they moved to Mississippi for a short time. In 1866, they settled on a farm near Helena, Arkansas. Caroline and Samuel had one daughter named Mildred.

The Art of Butter Sculpting

Caroline Shawk Brooks was the first known American artist to sculpt with butter. People often called her "The Butter Woman." She made her first butter sculpture in 1867. This was after her family's cotton crop failed, and she needed a way to earn extra money.

Many farm women at that time used butter molds to shape butter. But Caroline didn't just mold it; she sculpted it! She created shapes like shells, animals, and even faces. Instead of regular sculpting tools, she used "common butter-paddles, cedar sticks, broom straws and camel's-hair pencils." Her customers loved her detailed butter art. She made these sculptures for about a year and a half. Then she took a break for a few years.

Dreaming Iolanthe: A Famous Butter Sculpture

Caroline started making butter art again in 1873. She created a bas-relief (a sculpture that sticks out slightly from a flat surface) portrait. She gave it to a church fair. Her husband carefully carried it seven miles on horseback to the fair. The portrait sold and helped the church fix its roof. A man from Memphis saw her work and was so impressed. He asked her to create a butter portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots for his office.

In late 1873, Brooks read a play called King René's Daughter. It was written by a Danish poet, Henrik Hertz. The play is about a blind princess named Iolanthe. Her parents hid her blindness from her. She only learned the truth on her sixteenth birthday. Caroline was so inspired by Iolanthe's story. She created a butter sculpture called Dreaming Iolanthe. It showed the innocent girl just before she found out she was blind.

This sculpture was shown in a Cincinnati gallery in early 1874. It was a huge success! About two thousand people paid to see it during its two-week display. The New York Times newspaper wrote that the butter's "translucence" (how light shines through it) made the face look "rich" and "soft." They said "no other American sculptress has made a face of such angelic gentleness as that of Iolanthe."

The Centennial Exposition Demonstration

Brooks made other versions of Iolanthe. One was an alto-relievo (a sculpture that sticks out a lot from a flat surface). It was shown at the Centennial Exposition in 1876. This was a big world's fair held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her butter sculpture was in the Women's Pavilion and drew huge crowds.

She was asked to move to the main exhibit hall to show her sculpting skills. This was a great honor. But there was another reason for the invitation. Sometimes, people doubted if female artists truly created their own works. To prove she was the artist, Caroline sculpted another head in about 90 minutes. She did this in front of fair officials and reporters. Everyone was amazed by her speed and skill. She used simple tools and an unusual material. One guidebook called Dreaming Iolanthe the "most beautiful and unique exhibit in the Centennial."

Even though it was a demonstration, Caroline Brooks was seen as a serious artist. People believed her creations should be valued like sculptures made from traditional materials. One comment said that "the difficulties attached to the employment of such a material should be taken into account." It also praised her "high degree of talent" and "fine ideal feeling."

Life After the Centennial Exposition

After her success at the Centennial, Caroline Brooks traveled to many cities. She gave lectures and showed how she sculpted with butter. She visited New York, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Des Moines. In 1877, she demonstrated her art in Boston at Amory Hall. There, she created Pansy and The Marchioness. The Marchioness was her first full-length butter sculpture. Her daily shows in Boston helped her earn money for a trip to Europe.

Around this time, Caroline and her husband separated. Samuel stayed in Arkansas and became a state legislator in 1882. Caroline opened a studio in Washington, D.C. In 1878, she sculpted a life-size version of Dreaming Iolanthe in butter. She shipped it to be shown at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. She found it funny that customs officials listed her sculpture as "110 lbs. of butter" instead of a work of art.

Caroline later opened a studio in New York. From 1883 to 1886, she sculpted many portrait busts (sculptures of a person's head and shoulders). She finally had enough money to buy marble. She used marble to sculpt famous people like Thomas Carlyle, George Eliot, and James A. Garfield. She also created a group sculpture of Alicia Vanderbilt La Bau and her four children. Alicia was the daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Brooks showed her work at the Palace of Fine Arts and the Woman's Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Her exhibits included a butter bas-relief of Christopher Columbus. She also showed four marble sculptures: Lady Godiva Departing, Lady Godiva Returning, the Vanderbilt family portrait (renamed La Rosa), and a marble version of Dreaming Iolanthe.

She lived in San Francisco from 1896 to 1902. Not much is known about her last years. She kept a studio in her home after moving to St. Louis, Missouri. Caroline Shawk Brooks died in St. Louis in 1913. Very few of her artworks are still in public collections today. She is remembered as the "Centennial Butter Sculptress" and also as a pioneer for women artists.

Butter as an Art Medium: Challenges and Innovations

Working with, moving, and showing butter sculptures was very challenging for Caroline Brooks. To keep her delicate butter sculptures from melting, she made them in flat metal milk pans. These pans were placed in larger pans filled with ice. By adding more ice, she could keep her butter sculptures in good condition for months.

When she tried to sail from New York to France with a life-size butter sculpture, she had to wait. She needed to find a ship that had enough ice to keep her artwork cold for the whole journey. Then, she faced the problem of finding a train car with enough ice to safely transport the sculpture from Le Havre to Paris.

Brooks said she preferred butter over clay for sculpting. Clay had to be kept wet and wrapped to stop it from cracking. It was also not as easy to shape as butter. Plus, it was harder to make molds from clay. Caroline solved butter's main problem by using ice. She even found a way to use butter for casting.

After keeping her original butter Dreaming Iolanthe for six months, she wanted a way to preserve it without constant refrigeration. She poured plaster onto the butter sculpture. The plaster quickly hardened. She then cut a hole in the bottom of the milk pan holding her sculpture. She placed the pan over boiling water. The butter melted and drained out of the hole. She removed the rest of the pan, leaving a greased plaster mold. She put more plaster inside this mold. After some effort, she had a successful plaster copy. Caroline Brooks received a patent in 1877 for her method of making lubricated plaster molds. However, she preferred to sculpt a new butter piece for each exhibit instead of using plaster casts to reproduce them.

Other artists were inspired by Brooks to create butter displays. But most of them worked with dairy companies to promote their products at fairs. Caroline Brooks, however, dedicated her work to creating butter art purely for its artistic value.

See also

In Spanish: Caroline Shawk Brooks para niños

In Spanish: Caroline Shawk Brooks para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |