Celtic language decline in England facts for kids

The decline of Celtic languages in England was a historical process. It's about how the Brythonic languages spoken in early medieval England were replaced by West Germanic dialects. These dialects later became what we know as Old English.

Before the 5th century AD, most people in Great Britain spoke a Brythonic language. But this changed a lot during the Anglo-Saxon period (from the 5th to the 11th centuries). Experts still discuss if this change happened because many people moved or if it was a smaller military takeover. This situation was different from other places like France or Spain, where Germanic invaders slowly started speaking the local languages. So, understanding this language change helps us understand the big cultural shifts in post-Roman Britain, the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, and how the English language grew.

There were a few exceptions. The Cornish language was still spoken until the 18th century. Also, a form of Welsh was commonly used in the English counties along the Welsh border until the late 19th century.

Contents

How Languages Changed Over Time

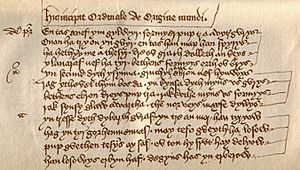

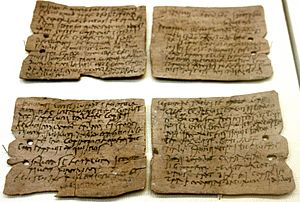

We have a good amount of information about languages in Roman Britain. This comes from Roman documents, place names, and personal names. We also have archaeological finds like coins and ancient writing tablets. These show that most people spoke British Celtic or British Latin, or both. The importance of British Latin decreased when the Roman economy and government structures collapsed in the early 5th century.

There isn't much direct information about languages in Britain for the next few centuries. However, by the 8th century, it was clear that Old English was the main language. Old English was brought to Britain mainly in the 5th and 6th centuries. It came with settlers from what is now the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark. These settlers spoke different Germanic languages and became known as Anglo-Saxons. The language that grew from their dialects is Old English. Some Britons moved west and across the channel to form Brittany. But those who stayed in what became England switched to speaking Old English. Celtic languages continued to be spoken in other parts of the British Isles, like Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and Cornwall. Only a few English words seem to have come from Brittonic into Old English.

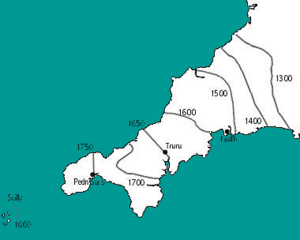

It's hard to know the exact timeline of how Old English spread. This is because the main evidence from 400–700 AD is archaeological, which doesn't often show language details. Also, written evidence after 700 AD is still limited. However, a scholar named Kenneth Jackson combined historical texts, like Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People, with evidence from river names. He suggested a timeline that is still widely accepted today (see map):

- In Area I, Celtic names are rare. This area became English-speaking around 500–550 AD.

- Area II shows English as the main language around 600 AD.

- In Area III, even many small streams have Brittonic names. English became dominant here around 700 AD.

- In Area IV, Brittonic remained the main language until at least the Norman Conquest. River names here are mostly Celtic.

While Cumbric in the north-west seems to have died out by the 11th century, Cornish continued to be strong until the early modern period. It retreated at about 10 kilometers per century. However, from about 1500, people started speaking both Cornish and English more often. Then, Cornish retreated faster, at about 30 kilometers per century. Cornish stopped being used entirely during the 18th century, though there has been an attempt to bring it back in recent decades. Welsh continued to be spoken in some western parts of Herefordshire and Shropshire into modern times.

During this period, England also had important communities speaking Latin, Old Irish, Old Norse, and Anglo-Norman. However, none of these languages seemed to be a major long-term rival to English or Brittonic.

Was Latin Replacing Celtic Before English Arrived?

There's an ongoing discussion about how much British Celtic was spoken and how much Latin was used in Roman Britain. It's now agreed that British Latin was spoken as a native language. Also, some big changes in Brittonic languages around the 6th century might have happened because Latin speakers switched to Celtic. This could have happened as Latin speakers moved away from Germanic-speaking settlers.

It seems likely that Latin was the language of most townspeople, government officials, the ruling class, the military, and the church. However, British Celtic probably remained the language of farmers, who made up most of the population. Wealthy people in the countryside were probably bilingual (spoke both languages). Some even suggest that Latin became the main language in lowland Britain. If so, the story of Celtic languages dying out in England started with Latin replacing them a lot.

One idea is that if people in Roman Lowland Britain already spoke both Brittonic and Latin, they might have found it easier to learn a third language, like the one spoken by the Germanic Anglo-Saxons.

Why So Little Celtic Influence on English?

Old English shows very little clear influence from Celtic or spoken Latin. There are extremely few English words that came from Brittonic.

The old explanation for this lack of Celtic influence was that Germanic-speaking invaders killed, chased away, or enslaved the previous inhabitants. This idea came from early historical accounts. In recent years, some experts still support similar ideas.

However, new studies of how languages interact today have given scholars new ways to understand the situation in early medieval Britain. Also, archaeological and genetic research suggests that a complete population change probably didn't happen in 5th-century Britain. Old texts even hint that people seen as Anglo-Saxon actually had British connections. For example, the West Saxon royal family was supposedly started by a man named Cerdic. His name comes from the Brittonic word Caraticos (like the Welsh Ceredig). His supposed descendants, Ceawlin and Caedwalla, also had Brittonic names. Other early Anglo-Saxon leaders and churchmen also had Brittonic names.

So, a different idea has been suggested: that a small number of politically powerful Old English speakers caused many Britons to adopt Old English. In this theory, if Old English became the most important language in an area, speakers of other languages would have tried to become bilingual. After a few generations, they would have stopped speaking the less important languages (like British Celtic or British Latin).

The collapse of Britain's Roman economy meant that Britons lived in a society similar to their Anglo-Saxon neighbors. This meant Anglo-Saxons didn't need to borrow words for new things. Sub-Roman Britain saw a bigger collapse of Roman systems compared to other places. This might have led to a dramatic drop in the importance of Roman culture in Britain. So, the Anglo-Saxons had little reason to learn British Celtic or Latin. Local people were more likely to give up their languages for the now more important language of the Anglo-Saxons. In these situations, Old English would borrow few words from the less important languages.

However, critics of this idea point out that usually, a small ruling class cannot force their language on a settled population. Also, archaeological and genetic evidence doesn't fully support either the idea of complete expulsion or just simple cultural change by a ruling class. In fact, many early migrants seem to have been families, not just warriors.

The current understanding among historians, archaeologists, and linguists is that the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain wasn't just one event. So, it can't be explained by just one idea. In the main settlement areas in the south and east, large-scale migration and population change seem to be the best explanations. In the areas to the northwest, a model where a powerful group influenced others might fit best. So, the decline of Brittonic and British Latin in England can be explained by a mix of migration, displacement, and cultural change in different places and times.

Some scholars have tried to find signs of Brittonic influence on English, especially in how English sounds, its grammar, and sentence structure. However, there is no clear agreement on these findings. Many of the suggested influences are also found in other Germanic languages or appeared much later in English history. It's a complex topic that linguists are still studying.

Why So Few Celtic Place-Names in England?

Place-names are important clues for understanding the history of language in post-Roman Britain for three main reasons:

- Even if recorded later, many names were probably created during the settlement period.

- Place-names might show how a wider group of people spoke, not just what was written down.

- They give us language evidence for areas where we don't have written records.

Place-names in England after the Roman period started to be recorded around 670 AD. Except in Cornwall, most place-names in England can easily be traced back to Old English (or Old Norse from later Viking influence). This shows how dominant English became across post-Roman England. This was often seen as proof of a huge cultural and population shift where Brittonic and Latin languages, place-names, and even speakers were swept away.

In recent decades, new research on Celtic toponymy has made this picture more complex. More names in England and southern Scotland have Brittonic or sometimes Latin origins than once thought. Earlier scholars often didn't notice this because they weren't familiar with Celtic languages. For example, Leatherhead was once thought to be Old English, but it's more likely from Brittonic lēd-rïd meaning 'grey ford'. There are also groups of Cumbric place-names in northern Cumbria. Even so, Brittonic and Latin place-names are very rare in the eastern half of England. They are more common in the western half, but still a tiny minority.

Also, some Old English names clearly refer to Roman structures or the presence of Brittonic-speakers. Names like Wickham came from the Latin word vicus (a type of Roman settlement). Others end in elements like -caster, from Latin castra (forts). There are many names like Walton or Walcot. Many of these likely include the Old English word wealh, which meant 'Celtic-speaker'. Names like Comberton probably include Old English Cumbre meaning 'Britons'. These names likely marked areas where Brittonic-speakers lived, but again, they are not very common.

In the last ten years, some scholars have pointed out that Welsh and Cornish place-names from the Roman period didn't survive much better than Roman names in England. This suggests that names were lost in Roman Britain, not just because of Anglo-Saxon arrivals. Other ideas for why Roman period place-names were replaced, which suggest a less dramatic shift to English naming, include:

- Adaptation instead of replacement: Names that look like Old English might actually come from Roman ones. For example, the Old English name for York, Eoforwīc, means 'boar-village'. We know the first part came from the earlier Roman-Celtic name Eburacum only because that name was recorded. Otherwise, we would think the Old English name was brand new.

- Invisible multilingualism: Place-names that only survive in Old English form might have had Brittonic versions for a long time, even if those weren't recorded. For example, the Welsh name for York, Efrog, comes from the Roman Eboracum independently. Other Brittonic names for English places might have continued alongside the English ones.

- Later evidence: Place-name records from later periods might not perfectly show what names were used right after the Roman period. Settlements and land ownership might have been unstable then, leading to many names being replaced. This allowed names created in the growing English language to quickly replace older Roman period names.

So, place-names are important for showing how quickly English spread across England. They also give us important clues about the history of Brittonic and Latin in the region. But they don't require a single, simple explanation for how English spread.

See also

- Sub-Roman Britain

- Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain

- History of English

- Brittonicisms in English

- List of English words of Brittonic origin

- Brittonic languages

- Last speaker of the Cornish language

- Language shift

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |