Channel Dash facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Channel Dash(Unternehmen Zerberus/Operation Cerberus) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Atlantic Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

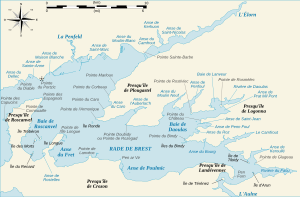

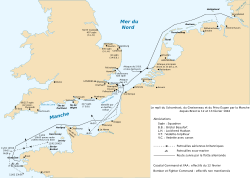

Diagram of the course taken by Operation Cerberus (in French) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2 battleships 1 heavy cruiser 6 destroyers 14 torpedo boats 26 E-boats 32 bombers 252 fighters |

6 destroyers 3 destroyer escorts 32 motor torpedo boats c. 450 aircraft |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 battleships damaged 1 destroyer damaged 1 destroyer lightly damaged 2 torpedo boats lightly damaged 22 aircraft destroyed (7 fighters) 13 sailors killed 2 wounded 23 aircrew killed (4 from JG 26) |

1 destroyer severely damaged Several MTBs damaged 42 aircraft destroyed 230–250 killed and wounded |

||||||

| Channel Dash (Unternehmen Zerberus/Operation Cerberus) |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Atlantic Campaign of the Second World War | |

| Type | Naval operation |

| Location | English Channel |

| Planned | late 1941 to February 1942 |

| Planned by | |

| Commanded by | |

| Objective | To reposition Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen from Brest to German ports |

| Date | 11–13 February 1942 |

| Executed by | Kriegsmarine Luftwaffe |

| Outcome | Success |

The Channel Dash (also known as Unternehmen Zerberus, or Operation Cerberus, named after a three-headed dog from Greek mythology) was a daring German naval operation during Second World War. It happened in February 1942. Three large German warships, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, along with their escort ships, sailed right through the English Channel. They moved from Brest in France to safe German ports.

These ships had been a big threat to Allied convoys (groups of supply ships) crossing the Atlantic Ocean. The British RAF Bomber Command had been trying to bomb them in Brest since March 1941. Both Gneisenau and Scharnhorst had been damaged by these attacks. In late 1941, Adolf Hitler ordered the German Navy to bring the ships back home. He wanted them closer to Norway, fearing a British invasion there. The shortest route was through the English Channel, which was risky but offered good air cover from the German air force, the Luftwaffe.

The British knew about the German ships because they could read secret German radio messages using the Enigma machine. They also used spy planes and agents in France to watch the ships. The British had a plan called Operation Fuller to stop the German ships if they tried to move. However, on February 11, 1942, the German ships left Brest and were not spotted for over 12 hours. They got very close to the Strait of Dover before the British realized what was happening.

The Luftwaffe provided strong air cover for the German ships. When the British finally reacted, their attacks by the RAF, Fleet Air Arm, Royal Navy, and coastal guns were mostly unsuccessful. Although Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were damaged by mines in the North Sea, they still reached German ports by February 13. This was seen as a big failure for the British. Winston Churchill ordered an investigation, and newspapers criticized the British response. The German Navy considered the operation a success because the ships reached their destination. However, it was a strategic failure because the ships were no longer a threat to Atlantic convoys. Later, Prinz Eugen was torpedoed off Norway, and Gneisenau was bombed and never sailed again. Scharnhorst was sunk in 1943.

Contents

Why the Ships Were in Brest

After Germany captured Norway and France in 1940, it became easier for their ships to attack British convoys in the North Atlantic. The cruiser Admiral Hipper arrived in Brest in December 1940. After being bombed by the RAF, it left in February 1941, sank many ships, and then returned to Germany by sailing around Britain.

The battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau also attacked British shipping in the Atlantic during the winter of 1940–1941. They sank many British ships. These two battleships arrived in Brest on March 22, 1941.

British Air Attacks on Brest

From January to April 1941, the RAF Bomber Command dropped many bombs on the German ships in Brest. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill made stopping German attacks on Atlantic convoys a top priority. British spy planes found Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in port on March 28.

The RAF flew many missions against the ships. Gneisenau needed engine repairs and entered a dry dock. An unexploded bomb was found under the ship, causing delays. Later, Gneisenau was torpedoed by a British aircraft, causing serious damage.

Gneisenau went back into dry dock and was hit by more bombs. These hits damaged its guns and crew quarters. Scharnhorst was not hit, but its repairs were delayed. This meant it missed a big German naval operation called Operation Rhine Exercise. During this operation, the German battleship Bismarck was sunk. After this loss, Hitler ordered his large warships to be much more careful.

During the summer, new British heavy bombers attacked the German ships. Prinz Eugen was hit and put out of action. Scharnhorst moved to La Pallice, another French port, to avoid attacks. However, it was still attacked by British bombers and hit five times.

The British continued to bomb and lay mines near Brest. From March to July, they dropped tons of bombs and laid many mines. They lost 34 aircraft in these attacks. Even though the British caused damage to the docks, the ships themselves were not hit again for a while.

Secret Intelligence: Ultra

The British used a secret system called Ultra. This system allowed them to read German radio messages that were encrypted (coded) by the Enigma machine. This information, along with spy plane photos and reports from agents, helped the British keep track of the German ships in Brest.

By April 1941, the British knew the ships had been hit, but not how badly. In December, Ultra messages showed that the German gunners were training in the Baltic Sea. This made the British suspect a breakout attempt was coming. In January 1942, photos showed the ships in the harbor. More German ships, like destroyers and torpedo boats, joined the big ships. This, plus news that the battleship Tirpitz had moved in Norway, made the British Admiralty (Navy headquarters) believe the three ships would try to sail through the Channel. They gave the order to start "Executive Fuller," their plan to stop the German fleet.

Hitler's Plan for Norway

In 1941, Hitler decided the Brest ships should return to Germany. He wanted them to help defend Norway from a possible British invasion. The German Navy leaders thought sailing through the English Channel was impossible. Hitler, however, wanted a "surprise break through the Channel." He ordered the operation to happen during bad weather, when most of the RAF planes would be grounded.

Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax planned for the ships to leave at night to surprise the British. They would pass through the narrowest part of the Channel, the Strait of Dover, during the day. This would allow them to have fighter plane cover from the Luftwaffe. Even though the Luftwaffe couldn't promise full protection, Hitler approved the plan. He also ordered the battleship Tirpitz to move south in Norway.

Getting Ready for the Dash

Operation Cerberus: The German Plan

Hitler chose the Channel route. Admiral Alfred Saalwächter was in charge of planning the operation. Vice Admiral Ciliax commanded the Brest Group. They planned the best route to avoid British minefields and sail at high speed. German minesweepers cleared paths through the mines and marked them with buoys.

U-boats (submarines) were sent to check the weather. More destroyers joined the escort ships. To have the longest period of darkness, the ships would leave four days before the new moon. They would also use the incoming tide to gain speed and possibly pass over mines.

The Luftwaffe was to provide air cover. Six destroyers would escort the ships at first, joined by more torpedo boats and smaller craft later. The German Navy and Luftwaffe practiced for the operation. By February 9, the ships were ready to sail on February 11. The crews were confident, and false rumors were spread to trick the British.

Operation Thunderbolt: Air Cover

Adolf Galland was put in charge of the air operation, called Unternehmen Donnerkeil (Operation Thunderbolt). The Luftwaffe brought in training units to make up for fighter planes fighting in the Soviet Union. They also tried to jam British radar and radio signals.

German bombers were ready to attack RAF bases and British naval forces. Reconnaissance planes watched both ends of the Channel. A special fighter controller was placed on Scharnhorst to talk to the Luftwaffe units. They practiced the operation eight times. Fighters were to fly high and low cover, with at least 16 fighters always on patrol. Each fighter sortie was timed to give 30 minutes of cover over the ships.

Operation Fuller: The British Plan

In April 1941, the Royal Navy and RAF created Operation Fuller. This plan was for combined attacks if the German ships left Brest. Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay was in charge of stopping a German squadron in the Channel. Coastal Command, the Navy, and the RAF would attack together.

British radar could detect ships far away, and air patrols were always flying. As soon as the alarm was raised, the plan would begin. British Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) would launch torpedo attacks. Fairey Swordfish and Bristol Beaufort torpedo-bombers would follow. Coastal guns at Dover would fire at the ships. If any ship was damaged and slowed down, Bomber Command would attack it.

As the German ships moved past Dover, destroyers from Harwich would attack with torpedoes. The RAF would continue bombing and lay mines. Bomber Command kept 100 aircraft ready. Fighter Command would provide escorts for the torpedo-bombers. All British forces had liaison officers to work together, but they didn't share a common communication system.

British Readiness

The British noticed German minesweeping and destroyers moving to Brest. This made the Admiralty think the German ships would try to dash through the Channel. They ordered six destroyers to be ready in the Thames and more torpedo boats to reinforce Dover. Two fast minelayers were sent to lay mines near Brest and Dover.

A British submarine, Sealion, was sent to patrol Brest Roads. Six Swordfish torpedo-bombers were moved closer to Dover. The RAF put its forces on alert. Coastal Command began night patrols with radar-equipped planes. On February 5, Enigma messages showed that Vice Admiral Ciliax had joined Scharnhorst, suggesting a departure was near.

On February 8, spy plane photos showed the ships still in harbor. Air Chief Marshal Philip Joubert de la Ferté, head of Coastal Command, warned that a sortie could happen any time after February 10. On February 11, Sealion found nothing and returned to recharge batteries. The German ships were supposed to leave at 7:30 p.m. but were delayed by a British bombing raid. However, Enigma messages had already revealed the German route, which was passed on to the British Navy.

The Battle Begins

Night of February 11/12

A British agent in Brest couldn't send a signal about the German ships leaving due to German radio jamming. The submarine Sealion had left its patrol to recharge. A British patrol plane was flying near Brest when the German ships gathered outside the port at 10:45 p.m. The plane's radar had a limited range and missed the ships. Another patrol plane also missed them.

A third patrol line, from Cherbourg to Boulogne, was called back at 6:30 a.m. because of fog. The German ships were still west of this line. This meant the German fleet was able to sail undetected for many hours.

February 12: Morning

The only British patrol over the Channel was a routine dawn flight. The German ships passed this patrol line at 10:00 a.m. From 8:25 a.m. to 9:59 a.m., RAF radar operators noticed German aircraft circling north of Le Havre. At first, they thought it was air-sea rescue. But at 10:00 a.m., they realized the radar plots were moving northeast.

Two Spitfire planes were sent to investigate. At 10:50 a.m., they landed and reported seeing a flotilla of ships off Le Touquet. At 11:05 a.m., news of the sighting reached British headquarters. By coincidence, two senior fighter pilots flew their own mission and spotted two large German ships, destroyers, and E-boats. They were attacked by German fighters but escaped. After landing at 11:09 a.m., they reported the German ships' exact position. By 11:25 a.m., the alarm was fully raised: the German fleet was entering the Straits of Dover with air cover.

At 11:27 a.m., Bomber Command was alerted. They had about 250 aircraft ready. However, many were loaded with bombs that needed to be dropped from high altitude, which was impossible due to poor visibility and low clouds. The commander ordered general-purpose bombs to be loaded, which would only cause surface damage. The goal was to distract the German ships for torpedo attacks.

February 12: Noon

Dover had powerful coastal guns. At 12:19 p.m., the Dover guns fired their first salvo. But visibility was poor, and they couldn't see where the shells landed. They hoped radar would detect the shell splashes, but it didn't work. The guns fired 33 rounds at the German ships, which were moving at 30 knots (about 35 mph). All shells missed. German sources said the fleet had already passed Dover when the guns opened fire. The coastal guns stopped firing when British naval forces and torpedo-bombers began their attacks.

February 12: Afternoon Attacks

The six Swordfish torpedo-bombers of 825 Squadron took off at 12:20 p.m. They were supposed to meet Spitfire escorts, but the escorts were late or missed them. The Swordfish, led by Lieutenant-Commander Eugene Esmonde, pressed on. Esmonde's plane was shot down before he could launch his torpedo. The other two planes in his section continued through heavy German anti-aircraft fire, dropped their torpedoes, and then crashed. The second section of three Swordfish also disappeared in the smoke and clouds. While German fighters were busy, some Australian Spitfires attacked German ships.

Five British Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) left Dover at 11:55 a.m. They spotted the German warships at 12:23 p.m. Their fighter cover was not ready. One MTB had engine trouble. The others found their path blocked by 12 German E-boats. The MTBs fired their torpedoes from far away, mistakenly claiming a hit on Prinz Eugen.

Seven Beaufort torpedo-bombers were closest to the German ships. Four of them took off at 1:25 p.m. They were late to meet their fighter escorts. The torpedo-bombers didn't receive updated orders because their radios were set up differently for this operation. Two Beauforts flew to the French coast, found nothing, and landed. The other two eventually attacked Prinz Eugen at 1,000 yards but had no effect.

More Beauforts from Scotland had to divert due to snow. Nine of them took off at 2:25 p.m. They reached Manston at 2:50 p.m. and tried to form up with other planes, but there was confusion. The Beaufort commander eventually set off alone. Six Hudson planes followed and attacked the German ships, but two were shot down. Six Beauforts also attacked through heavy fire, but their torpedoes had no effect.

The first wave of 73 heavy bombers took off from 2:20 p.m. Most found the target area, but thick clouds and rain hid the ships. Only ten crews could see the ships well enough to bomb. The next wave of 134 bombers also faced bad weather. Only about 20 managed to bomb. The last wave of 35 aircraft also had limited success. In total, only 39 aircraft managed to attack, and 15 bombers were shot down. No hits were achieved.

Six British destroyers from Nore Command were practicing gunnery when alerted at 11:56 a.m. They sailed south to intercept the German fleet. To catch up, they sailed over a German minefield. At 2:31 p.m., Scharnhorst hit a mine north of the Scheldt Estuary. It stopped for a short time but then continued at 25 knots.

At 3:17 p.m., the destroyers made radar contact. At 3:43 p.m., they saw the German ships. One destroyer had engine trouble and dropped out. The other five attacked. They were immediately fired upon by the German ships. Two destroyers fired torpedoes. Worcester closed in further and was hit by fire from Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen. The last two destroyers attacked, but all their torpedoes missed. Worcester was badly damaged but managed to limp back to port.

Night of February 12/13 and February 13

Scharnhorst had fallen behind after hitting a mine. At 7:55 p.m., Gneisenau hit a magnetic mine off Terschelling. The explosion caused a small hole and temporarily stopped a turbine. After 30 minutes, the ship continued. As Scharnhorst sailed through the same area, it hit another mine at 9:34 p.m. Both main engines stopped, and steering was lost. The ship got moving again at 10:23 p.m. and arrived at Wilhelmshaven at 10:00 a.m. on February 13. Its damage took three months to repair.

Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen reached the Elbe river at 7:00 a.m. and docked at Brunsbüttel. The British had laid many magnetic mines along the German route after getting intelligence from Enigma. The fact that the German ships hit mines was kept secret by the British to protect their intelligence source.

What Happened Next

Losses

The British lost many aircraft during the Channel Dash. These included Blenheims, Whirlwinds, Wellingtons, Hurricanes, Hampdens, and Spitfires. German gunners shot down all six Swordfish and a Hampden bomber. The British destroyer Worcester lost 23 men killed, and 45 were wounded. The ship was out of action for 14 weeks. In total, about 230–250 British personnel were killed or wounded.

The German torpedo boats Jaguar and T. 13 were damaged by bombing. Two German sailors were killed, and several were wounded. The Luftwaffe lost 17 aircraft and 11 pilots.

Later Operations

Gneisenau entered a dry dock at Kiel. It was hit twice by RAF bombers on the night of February 26/27. One bomb caused a fire that detonated a magazine, blowing off a forward gun turret. The damage was so severe that the German Navy decided to rebuild Gneisenau with larger guns, but this work was later stopped. The ship never sailed again.

On February 23, Prinz Eugen was torpedoed by a British submarine off Norway. It was out of action until October. It spent the rest of the war in the Baltic Sea. On March 28, the British raided St Nazaire in Operation Chariot and destroyed a large dry dock. This dock was the only one in France big enough for the largest German warships. Scharnhorst later took part in an operation against Spitzbergen in September 1943. It was eventually sunk at the Battle of the North Cape on December 26, 1943.

Remembering the Channel Dash

A granite memorial was put up in Marine Parade Gardens in Dover. It honors all Britons involved in Operation Fuller. This happened for the 70th Anniversary of the event in 2012. Sailors from HMS Kent provided a Guard of Honor during the unveiling ceremony.

On February 10, 2017, a ceremony and flypast took place at the Fleet Air Arm memorial church. Four Wildcat HMA2 helicopters from 825 Naval Air Squadron flew over. This marked the 75th anniversary of Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde and 825 Naval Air Squadron's brave attack.

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |