Chartwell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chartwell |

|

|---|---|

View of Chartwell from the north-east

|

|

| Type | Country house |

| Location | Westerham, Kent, England |

| Built | Early modern period |

| Rebuilt | 1922–24 |

| Architect | Philip Tilden (1920s) |

| Architectural style(s) | Vernacular |

| Owner | National Trust |

|

Listed Building – Grade I

|

|

| Official name: Chartwell | |

| Designated | 16 January 1975 |

| Reference no. | 1272626 |

| Official name: Chartwell Garden | |

| Designated | 1 May 1986 |

| Reference no. | 1000263 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Chartwell is a beautiful country house located near Westerham, Kent, in South East England. For over 40 years, it was the beloved home of Sir Winston Churchill, a famous British leader. He bought the house in September 1922 and lived there until just before he passed away in January 1965.

During the 1930s, when Churchill was not in a government role, Chartwell became the most important place in his life. He invited many people to his dining table to discuss how to stop German re-armament and the British government's policy of appeasement (trying to avoid war by giving in to demands). In his study, he wrote speeches and books. In his garden, he even built walls and lakes with his own hands, and he loved to paint.

During the Second World War, the Churchill family mostly stayed away from Chartwell for safety. They returned after Churchill lost the 1945 election. In 1953, when he was again prime minister, the house became a peaceful retreat for him after he had a stroke. He left Chartwell for the last time in October 1964 and passed away in London in January 1965.

The Chartwell estate has a long history, dating back to the 14th century. It was sold many times before Churchill bought it. Between 1922 and 1924, the house was rebuilt and made larger by the architect Philip Tilden. From the garden, the house has amazing views over the Weald of Kent. Churchill said it was "the most beautiful and charming" view he had ever seen, which helped him decide to buy the house.

In 1946, Churchill faced money problems and thought about selling Chartwell. However, a group of his friends, led by Lord Camrose, raised money to buy the house for the National Trust. This allowed the Churchills to continue living there for the rest of their lives. After Churchill's death, Lady Churchill gave up her rights, and the National Trust opened Chartwell to the public in 1966 as a historic house museum. Chartwell is a Grade I listed building, meaning it's very important historically. It has become one of the National Trust's most popular places to visit. In 2016, 232,000 people visited the house.

History of Chartwell

Early Days to 1922

The land where Chartwell stands was first mentioned in records in 1362. The name "Chart Well" comes from a spring near the house, with "Chart" being an old English word for rough ground. A house has been on this site since at least the 16th century. It was once called Well Street. Some people say Henry VIII stayed here when he was trying to win over Anne Boleyn at nearby Hever Castle. You can still see some 16th or 17th-century brickwork in the walls today.

For many years, the house was a farmhouse and changed owners often. In 1848, John Campbell Colquhoun bought it. His family made the house much bigger, adding features like stepped gables, which are common in Scottish buildings. By the time Churchill bought it, the house was described as a large, imposing mansion.

Churchill's Time at Chartwell

1922 to 1939: Making it Home

Winston Churchill first saw Chartwell in July 1921. He loved the location and the views. In September 1922, he bought the house for £5,000. He knew the house needed a lot of work because of "dry rot" and other issues. The seller was Captain Archibald John Campbell Colquhoun, who had been to school with Churchill. Churchill wrote to him, "I am very glad indeed to have become the possessor of 'Chartwell'. I have been searching for two years for a home in the country and the site is the most beautiful and charming I have ever seen."

The years before buying Chartwell had been tough for Churchill. His mother passed away, then his youngest child, Marigold. He also lost his political seat in Dundee.

Churchill hired Philip Tilden to rebuild the house in 1922. The family rented a nearby farmhouse while the work was done. The building project took two years and cost much more than expected, going from £7,000 to over £18,000. This caused some arguments between Churchill and the architect. Churchill's wife, Clementine, also worried a lot about the costs. In September 1923, Churchill wrote to her, "My beloved, I beg you not to worry about money, or to feel insecure. Chartwell is to be our home (and) we must endeavour to live there for many years." Churchill finally moved into the house in April 1924.

Chartwell was not just a holiday home for Churchill. He often invited friends and political colleagues to visit. He used these visits to discuss important political matters. For example, in 1926, his colleague Sir Samuel Hoare visited and noted Churchill was more interested in building ponds than anything else. In 1928, James Lees-Milne described Churchill using decanters and wine glasses to explain the Battle of Jutland after dinner, making "barking noises in imitation of gunfire."

Churchill also loved to paint at Chartwell. He wrote long letters to Clementine, called Chartwell Bulletins, describing the work on the house and gardens, and his new interest in painting. He even had the artist Sickert visit to give him lessons.

In the late 1930s, Chartwell became a hub for Churchill's efforts to warn Britain about the dangers of Hitler and German rearmament. Many people, including friends, government officials, and foreign visitors, came to Chartwell to share information and support Churchill's fight against appeasement. The house became like his own "little Foreign Office." He used the information he gathered to form his opinions and write his speeches.

1939 to 1965: Wartime and Later Years

During the Second World War, Chartwell was mostly empty. Its location made it unsafe from German air attacks or commando raids. The lakes were even covered with brushwood to hide the house from the air. Churchill and his wife spent most weekends at other secure locations like Ditchley House or Chequers.

However, Chartwell remained a place of comfort for Churchill during difficult times. He spent the night there before the fall of France in 1940. He also visited in June 1941 after a military failure in North Africa, where he thought deeply about the war. His secretary noted him feeding his goldfish, even during such serious moments.

After VE Day in May 1945, the Churchills returned to Chartwell. A large crowd greeted them. But soon after, Churchill lost the general election in July 1945. He again thought about selling Chartwell because it was expensive to run. But his friends, led by Lord Camrose, raised £55,000 to allow the National Trust to buy the house. This meant the Churchills could live there for the rest of their lives for a small rent, and after their deaths, it would become a public museum.

In 1953, while he was prime minister again, Churchill suffered a stroke. He was taken to Chartwell to recover. His friends worked together to keep his illness a secret from the press, which was very unusual. Hidden and protected at Chartwell, Churchill made an amazing recovery. During this time, he also finished writing Triumph and Tragedy, the last book in his war memoirs.

On April 5, 1955, Churchill led his last government meeting. The next day, he drove to Chartwell. When a journalist asked how it felt not to be prime minister, Churchill replied, "It's always nice to be home." For the next ten years, he spent much of his time at Chartwell, writing, painting, playing cards, or feeding his golden orfe fish in the pond. His daughter, Mary Soames, remembered him in his later years, "contemplating the view of the valley he had loved for so long."

Churchill's last dinner guests at Chartwell were in October 1964. The following week, he left the house for the last time, as he was becoming weaker. He passed away in January 1965. After his death, Lady Churchill gave Chartwell to the National Trust, and it opened to the public in 1966.

National Trust: 1966 to Today

The National Trust has carefully restored Chartwell to look as it did in the 1920s and 1930s. Churchill had wanted it to be "furnished so as to be of interest to the public." The rooms are filled with his belongings, gifts, original furniture, books, and the awards he received.

The house is very popular. In 2016, 232,000 people visited Chartwell. That year, the National Trust started an appeal to buy hundreds of Churchill's personal items that were on loan from his family. These items include his Nobel Prize in Literature, which he received in 1953. The award was given to him for his amazing writing and powerful speeches. The Nobel medal is displayed in the museum room at Chartwell.

Inside and Outside Chartwell

The Chartwell estate is on a high point, about 650 feet above sea level. From the house, you can see wide views across the Weald of Kent. This view was very important to Churchill. He once said, "I bought Chartwell for that view."

Outside the House

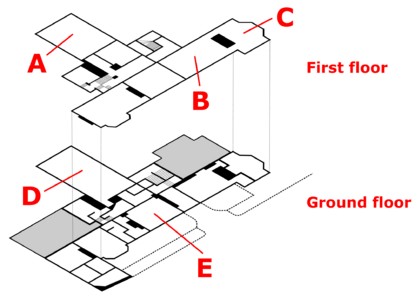

Churchill hired architect Philip Tilden to update and expand the house from 1922 to 1924. The house is built of red brick and has two main floors, plus a basement and attics. The front entrance has an 18th-century doorway that Churchill bought from an antique dealer. On the garden side, Tilden added a large, three-story section with stepped gables, which Churchill called "my promontory." This part of the house holds the dining room, drawing room, and Lady Churchill's bedroom.

Inside the House

The inside of Chartwell has been set up by the National Trust to welcome visitors and display many items related to Churchill. Some guest bedrooms have been combined to create the Museum room and Uniform room. However, most of the main rooms look just as they did in the 1920s and 1930s and are open to the public.

Entrance Hall, Library, and Drawing Room

The entrance halls lead to the library, drawing room, and Lady Churchill's sitting room. The library has important items, including a portrait of Churchill from 1942 and a model of Port Arromanches, showing the Normandy landing site during World War II. The drawing room was mainly used for guests and playing cards. It has a famous painting of Charing Cross Bridge by Claude Monet.

Dining Room

The dining room is in the lower part of the "promontory" extension. It has the original dining table and chairs designed by Heal's to Churchill's exact wishes. A painting study by William Nicholson hangs here, showing the Churchills having breakfast, which they rarely did together. The painting also shows Churchill's marmalade cat, Tango. The National Trust continues the tradition of having a marmalade cat at Chartwell, just as Churchill wanted.

Churchill himself painted the dining room in one of his pictures, Tea at Chartwell: 29 August 1927. It shows him with his family and friends. Above the dining room is the drawing room, and above that, Lady Churchill's bedroom, which Churchill called "a magnificent aerial bower."

Churchill's Study

Churchill's study, on the first floor, was his "workshop for over 40 years" and "the heart of Chartwell." In the 1920s, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he planned budgets here. In the 1930s, he wrote speeches warning about Hitler and dictated books to earn money. After losing the 1945 election, he came here to write his histories. And in his final retirement, he spent much of his old age here.

The study has three banners hanging from the ceiling: Churchill's flags as a Knight of the Garter and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, and the Union Flag that flew over Rome when it was freed in 1944. This flag was a gift from Lord Alexander of Tunis. The study also has portraits of Churchill's parents. The floor is covered with a beautiful carpet, a gift from the Shah of Iran in 1943.

Next to the study are Churchill's bedroom and bathroom. These rooms were not open to the public for many years, but Churchill's daughter, Mary, gave permission for them to be opened before she passed away in 2014.

Architectural Style

Chartwell is not famous for its architectural beauty, but for its historical importance. The house is a Grade I listed building because of its connection to Winston Churchill. The gardens are also very important and are Grade II* listed.

Gardens and Estate

The gardens around the house cover about 8 hectares (20 acres), with another 23 hectares (57 acres) of parkland. The Churchills created most of the gardens you see today. The garden side of the house opens onto a terraced lawn. To the north is the rose garden, designed by Lady Churchill. The nearby Marlborough Pavilion was decorated with paintings by Churchill's nephew in 1949. Beyond the rose garden is the water garden, which includes the golden orfe pond where Churchill loved to feed his fish. There's also a swimming pool built in the 1930s.

To the south is the croquet lawn. Churchill loved to build things. He became interested in bricklaying after buying Chartwell and built walls, a summerhouse, and some small houses on the estate. He even joined a builders' union in 1928! Near the kitchen garden is the golden rose walk, with 32 types of golden roses, a gift for the Churchills' 50th wedding anniversary in 1958. Churchill's painting studio, built in the 1930s, now holds many of his artworks.

South of the terrace lawn are the upper and lower lakes, which were part of Churchill's big landscaping projects. He created the island in the lower lake and built the upper lake himself. He even used a large mechanical digger to help with the work.

On the lakes lived Churchill's collection of wildfowl, including black swans, which were a gift from the Australian Government. Churchill loved the animals at Chartwell. His friend Violet Bonham Carter remembered him being delighted to see two Red Admirals (butterflies) on the Buddleia bushes he had planted to attract them.

Farms and Stables

After the war, Churchill bought more land around Chartwell, including Chartwell Farm and Parkside Farm. By 1948, he was farming about 500 acres. His son-in-law, Christopher, managed the farms. Churchill kept cattle and pigs and grew crops. However, the farms didn't make money, and he eventually sold them.

A more successful hobby for Churchill was owning and breeding racehorses. In 1949, he bought a horse named Colonist II, who won many races and earned Churchill a lot of money. By 1961, his total prize money from racing was over £70,000. He once said that perhaps his horse was a comfort to him in his old age.

See also

- 28 Hyde Park Gate (Churchill's home in London)

- Blenheim Palace (Churchill's birthplace in Oxfordshire)

- Churchill Archives Centre (Cambridge)

- Churchill War Rooms (London)

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |