Chevalier de Saint-Georges facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

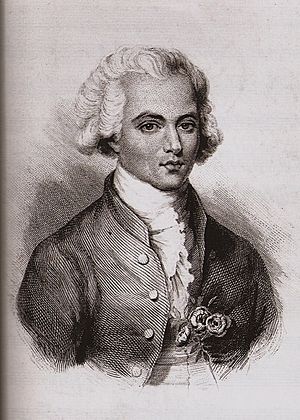

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

|

|

|---|---|

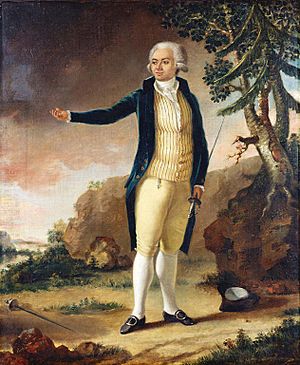

Saint-Georges, posing with his fencing foil, by Mather Brown, 1787

|

|

| Born | 25 December 1745 Baillif, Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe

|

| Died | 10 June 1799 (aged 53) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Académie royale polytechnique des armes et de l'équitation |

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (born December 25, 1745 – died June 10, 1799) was a famous French musician. He was a talented violinist and composer. He also led a major symphony orchestra in Paris.

Saint-Georges was born in Guadeloupe, which was a French colony then. His father was a rich plantation owner named Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges. His mother was an enslaved African woman named Nanon. When he was seven, he moved to France. At thirteen, he trained to be a gendarme, a type of police officer for the King.

He learned music from François-Joseph Gossec and probably violin from Jean-Marie Leclair. He also kept practicing fencing, where he was very skilled.

In 1769, he joined a new orchestra. Two years later, he became its concertmaster, which is the lead violinist. Soon after, he started composing his own music. By 1773, he was the conductor of "Le Concert des Amateurs."

He introduced a new type of music called the symphonie concertante. In 1776, he was considered to lead the Paris Opera. However, some singers protested because of his mixed race, and he was not given the job.

Saint-Georges was friends with many famous composers. These included Antonio Salieri, François-Joseph Gossec, Gretry, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Christoph Willibald von Gluck. He became the conductor of "Le Concert de la Loge Olympique." This orchestra was very large. In 1784, he asked Joseph Haydn to write six symphonies for them. These are now known as Haydn’s "Paris" symphonies.

In 1787, he traveled to London. There he met the Prince of Wales and King George III.

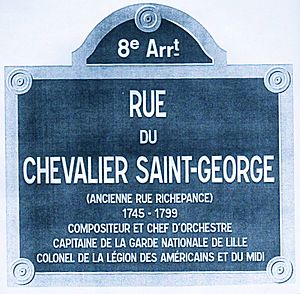

When the French Revolution began in 1789, Saint-Georges was almost 45. He became a colonel in the Légion St.-Georges. This was the first all-black regiment in Europe. They defended the new French Republic.

Today, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges is remembered as one of the first European musicians of African descent to become famous. He was a leading figure in Parisian music. He wrote many string quartets, sonatas, and symphonies. He also composed several violin concertos and operas. He even wrote a children’s opera.

Contents

Early Life and Fencing

Joseph Bologne was born in Baillif, Basse-Terre. His father, Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges, was a planter. His mother, Nanon, was an enslaved African servant. Even though his father was married to another woman, he recognized Joseph as his son. He gave Joseph his last name.

His father was called "de Saint-Georges" after one of his plantations. In France, laws like the Code Noir made it hard for people of color. They faced racism and could not easily marry into high society.

In 1753, Joseph's father brought him to France for school. Joseph was seven years old. Two years later, his mother Nanon also came to Paris. They lived in a large apartment.

At 13, Joseph joined a fencing school. His progress was very fast. By 15, he was beating top swordsmen. At 17, he was incredibly quick. He famously beat a fencing master who had insulted him. This victory was a big deal. His father was proud and gave him a horse and buggy.

In 1766, Joseph graduated. He became a Gendarme du roi, an officer in the king's bodyguard. He was also made a chevalier, which means knight. From then on, he was known as the "Chevalier de Saint-Georges."

When his father died in 1774, he left Joseph money. Joseph's mother also made sure he was taken care of. Saint-Georges was admired for his fencing and riding. He was a role model for young athletes. He was also a good dancer and was invited to many fancy parties.

Revolution and Later Life

Saint-Georges faced racism because of his mixed race. When the French Revolution began, he supported it. The revolution declared equal rights for all French people. In 1791, he was the first to volunteer for the French National Guard in Lille.

In 1792, a special cavalry unit was formed. It was for volunteers from the West Indies and Africa. It was often called the "Légion St-Georges" because of Colonel Saint-Georges's great leadership.

Later, Saint-Georges was criticized for being involved in non-revolutionary activities. He was dismissed from his command and put in prison for 18 months. Even though his soldiers supported him, he was not allowed to lead them again after his release.

He went to Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) for a while. There was a civil war there. Disappointed, he returned to France. In 1797, he tried to rejoin the army but was refused.

On June 10, 1799, Saint-Georges died from an illness.

Musical Life and Career

We don't know much about Saint-Georges's early music lessons. But he must have practiced a lot to become so skilled. In 1764, violinist Antonio Lolli wrote two concertos for him. In 1766, composer François-Joseph Gossec dedicated six string trios to him. Lolli might have taught him violin, and Gossec might have taught him composition.

In 1769, Saint-Georges surprised everyone by playing violin in Gossec's new orchestra, Le Concert des Amateurs. Four years later, he became its leader. In 1772, he played his first two violin concertos as a soloist. People loved his performances and compositions.

Saint-Georges's first published works were six string quartets. These were among the first in France. He wrote more string quartets, sonatas for piano and violin, and violin duets. He also wrote 12 more violin concertos, two symphonies, and eight symphonie-concertantes. These were a new type of music in Paris, and he was a master of them.

In 1773, Gossec left the Concert des Amateurs. He chose Saint-Georges to take over as director. Under Saint-Georges's leadership, the orchestra became known as the best symphony orchestra in Paris, and maybe all of Europe.

In 1781, Saint-Georges's orchestra had to stop because of money problems. But his friend, Philippe D'Orléans, helped. He restarted the orchestra as part of a special group called the Loge Olympique.

The orchestra was renamed Le Concert Olympique. In 1785, Saint-Georges asked Joseph Haydn to write six new symphonies for them. Saint-Georges conducted these "Paris" symphonies. They were very popular. Even Queen Marie Antoinette attended some of his concerts.

Operas

In 1776, the Paris Opera was having problems. Saint-Georges was suggested as the new director. He was a great choice because he had built a very good orchestra. However, some leading singers protested. They said they could not work for a "mulatto."

To avoid a scandal, the King took control of the Opera. Queen Marie-Antoinette then preferred to have music at her palace. Saint-Georges was invited to play music with the Queen there. He probably played his violin sonatas with her playing the piano.

The singers' protest may have stopped Saint-Georges from getting higher musical positions. But he continued to compose. He wrote two more violin concertos and symphonies. After that, he focused more on writing operas.

His first opera, Ernestine, was performed in 1777. Critics liked the music but not the story. The Queen attended, but the audience's reaction led her to leave early.

After this, the Marquise de Montesson hired Saint-Georges. She made him music director of her private theater. He even got an apartment in her mansion. For a time, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart also stayed there.

Saint-Georges wrote his second opera, La Chasse, at the mansion. It was much more successful. His most popular opera was L'amant anonyme.

In 1785, the Duke of Orléans died. Saint-Georges lost his positions and apartment. His friend, Philippe, the new Duke of Orléans, gave him a small flat. Saint-Georges became involved in the political activities around Philippe.

The Duke's plans for the Palais-Royal left the Orchestre Olympique without a home. Saint-Georges was unemployed. Philippe then sent Saint-Georges to London. He wanted Saint-Georges to meet the Prince of Wales. This was to get the Prince's support for Philippe.

London and Lille

In London, Saint-Georges stayed with fencing masters Domenico Angelo and his son Henry Angelo. They arranged fencing matches for him. One match was at Carlton House before the Prince of Wales. He even fenced with the famous La Chevalière D'Éon.

Saint-Georges also played one of his concertos at a music society. He met with British leaders who were against slavery. He delivered a request from a French anti-slavery group. Before he left England, Mather Brown painted his portrait.

Back in Paris, he produced his opera La Fille Garçon. Critics still found the story weak, but they liked his music. The Duke of Orléans opened new theaters. Saint-Georges wrote music for a children's puppet theater. This was for an opera called Le Marchand de Marrons (The Chestnut Vendor).

In 1789, Saint-Georges attended a meeting where the slave trade was called "barbarous." He was strongly against slavery.

In London, Saint-Georges continued his anti-slavery work. He helped translate British anti-slavery writings into French. He was once attacked by several men. Some believed it was an assassination attempt because of his work against slavery.

In 1790, Saint-Georges went to Lille for a fencing tournament. He was ill but still performed with great skill. He then became very sick for six weeks. While recovering, he composed an opera for Lille's theater company. It was called Guillome tout Coeur, ou les amis du village. This was his last opera.

He continued to face racism. In one town, a hotel refused to serve him because he was a person of color. He remained calm despite this.

Tired of politics, Saint-Georges decided to serve the Revolution directly. In 1790, he joined the Garde Nationale in Lille. He also continued to give concerts. The mayor of Lille honored him with a crown of laurels.

In 1792, France declared war. Captain Saint-Georges, who had been promoted, commanded a company of volunteers. They bravely held their ground in a battle near the Belgian border.

Saint-Domingue and Final Years

News of the French Revolution reached Saint-Domingue. This led to a slave revolt. Toussaint Louverture became the leader of the revolt. In 1796, a French commission sailed to Saint-Domingue to end slavery. Saint-Georges, as an experienced officer, likely went with them.

After this difficult journey, Saint-Georges returned to Paris. He started a new symphony orchestra called Le Cercle de l'Harmonie. This group aimed to bring back the elegance of his old orchestra. Despite some claims that he lived in poverty, he was still leading a respected musical group.

Saint-Georges said that towards the end of his life, he was especially dedicated to his violin. He felt he played it better than ever.

In 1799, bad news came from Saint-Domingue. A war had started between different groups. This news affected Saint-Georges, who was already ill. He died on June 10, 1799, at the age of 53. His friend, Captain Nicholas Duhamel, cared for him until the end.

Works

Operas

- Ernestine, a comic opera in 3 acts (1777). Most of it is lost.

- La Partie de chasse, a comic opera in 3 acts (1778). Most of it is lost.

- L'Amant anonyme (The Anonymous Lover), a comic opera in 2 acts (1780). The full music for this opera still exists.

- La Fille garçon, a comic opera in 2 acts (1787). Lost.

- Aline et Dupré, ou le marchand de marrons, a children's opera (1788). Lost.

- Guillaume tout coeur ou les amis du village, a comic opera in one act (1790). Lost.

Symphonies

- Deux Symphonies à plusieurs instruments, Op. XI, No. 1 in G and No. 2 in D.

- Note: No. 2 is the same as the overture to his opera, L'Amant anonyme.

Concertante

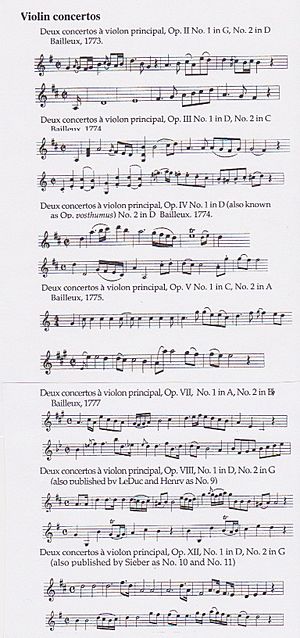

Violin concertos

Saint-Georges composed 14 violin concertos. Here are some of them:

- Op. II, No. 1 in G and No. 2 in D (1773)

- Op. III, No. 1 in D and No. 2 in C (1774)

- Op. IV, No. 1 in D and No. 2 in D (1774)

- Op. V, No.1 in C and No. 2 in A (1775)

- Op. VII, No. 1 in A and No. 2 in B-flat (1777)

- Op. VIII, No. 1 in D and No. 2 in G (published later)

- Op. XII, No. 1 in E-flat and No. 2 in G (1777)

Symphonies concertantes

- Op. VI, No. 1 in C and No. 2 in B-flat (1775)

- Op. IX, No. 1 in C and No. 2 in A (1777)

- Op. X, for two violins and viola, No. 1 in F and No. 2 in A (1778)

- Op. XIII, No. 1 in E-flat and No. 2 in G (1778)

Chamber music

Sonatas

- Trois Sonates for keyboard with violin (c. 1770, published 1781).

- Sonata for harp with flute (undated).

- Six Sonatas for violin accompanied by a second violin (published 1800).

- Cello Sonata (lost).

String quartet

- Six quatuors à cordes (Six string quartets), Op. 1 (1773).

- Six quartetto concertans "Au gout du jour" (Six concertante quartets "In the style of the day") (1779).

- Six Quatuors concertans, oeuvre XIV (Six concertante quartets, Op. 14) (1785).

Vocal music

He also wrote several songs and duets for voice and orchestra. Many of these came from his operas.

Discography

Many of Saint-Georges's works have been recorded. You can find recordings of his symphonies, violin concertos, and chamber music.

Symphonies concertantes

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. IX No. 1 in C

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. IX No. 2 in A

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. X No. 1 in F

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. X No. 2 in A

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. XIII in G

Symphonies

- Symphony Op. XI No. 1 in G

- Symphony Op. XI No. 2 in D

Violin concertos

- Concerto Op. II, No. 1 in G

- Concerto Op. II, No. 2 in D

- Concerto Op. III, No. 1 in D

- Concerto Op. III, No. 2 in C

- Concerto Op. IV, No. 1 in D

- Concerto Op. IV, No. 2 in D

- Concerto Op. V, No. 1 in C

- Concerto Op. V No. 2 in A

- Concerto Op. VII No. 1 in A

- Concerto Op. VII No. 2 in B-flat

- Concerto Op. VIII, No. 1 in D

- Concerto Op. VIII, No. 2 in G

- Concerto Op. XII, No. 1 in D

- Concerto Op. XII, No. 2 in G

Chamber music

- String Quartets: Op. 1, "Au gout du jour", and Op. 14.

- Three keyboard and violin sonatas (Op. 1a).

Miscellaneous

- Adagio in F minor

- Airs from his opera Ernestine

- Excerpts from his opera L'Amant anonyme

Images for kids

-

Portrait of George IV as Prince of Wales in 1785 by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

-

Charlotte-Jeanne Béraud de la Haie de Riou, marquise de Montesson, after Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun

See also

In Spanish: Chevalier de Saint-Georges para niños

In Spanish: Chevalier de Saint-Georges para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |