Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal |

|

|---|---|

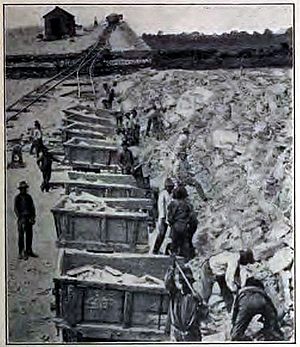

Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (at the time named the Chicago Drainage Canal) being built

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 28 miles (45 km) |

| Locks | 1 |

| Status | Open |

| History | |

| Former names | Chicago Drainage Canal |

| Date completed | January 2, 1900 |

| Date extended | 1907 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Des Plaines River north of Joliet, Illinois (41°33′19″N 88°04′40″W / 41.5552°N 88.0778°W) |

| End point | South Branch Chicago River in Chicago, Illinois (41°50′41″N 87°39′53″W / 41.8447°N 87.6648°W) |

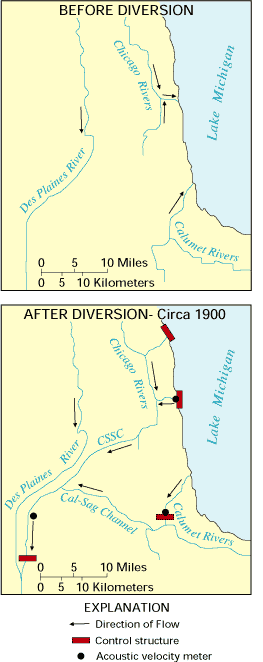

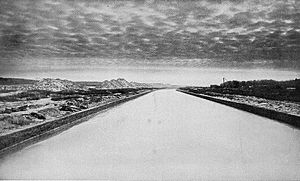

The Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, also known as the Chicago Drainage Canal, is a 28-mile (45 km) long waterway. It connects the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River. This amazing canal actually changed the direction of the Chicago River. Now, the river flows out of Lake Michigan instead of into it!

Another channel, the Calumet-Saganashkee Channel, does the same for the Calumet River nearby. These two canals are super important. They are the only way for ships to travel between the Great Lakes Waterway and the Mississippi River system.

The main reason for building this canal was to help with sewage treatment. Before 1900, Chicago's sewage went right into the Chicago River. This meant it flowed into Lake Michigan, which was also where the city got its drinking water. People worried that sewage could mix with drinking water and make everyone sick. So, engineers decided to reverse the river's flow. This sent the sewage away from the lake, towards the Des Plaines River, where it could be treated.

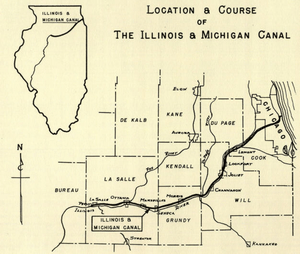

The canal also had another big goal. It was built to replace an older, smaller canal called the Illinois and Michigan Canal (I&M). The I&M Canal had connected Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River since 1848. The new canal was made much wider and deeper. It is 202 feet (62 meters) wide and 24 feet (7.3 meters) deep. This is more than three times bigger than the old I&M Canal! The I&M Canal was used less after the new one opened. It closed completely in 1933.

Building the Chicago canal was a huge learning experience for engineers. Many of them later used their skills to build the famous Panama Canal. Today, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago manages the canal. In 1999, it was even named a "Civil Engineering Monument of the Millennium." This means it's one of the most important engineering projects of its time!

Contents

Why Was the Canal Built?

Chicago faced a big problem with its water. Early sewage systems sent waste directly into Lake Michigan. This was also where the city got its drinking water. The water came from special "cribs" located two miles offshore. People were very worried that sewage would get into the drinking water. This could cause serious illnesses like typhoid fever.

In 1885, a huge storm washed a lot of waste from the river far into the lake. This caused a panic. People feared a similar storm could lead to a terrible sickness outbreak. Luckily, the weather was cooler than usual, which helped prevent a disaster. Because of this close call, the Sanitary District of Chicago was created in 1889. This group was in charge of fixing the problem.

The canal was also built to improve shipping. The older Illinois and Michigan Canal (built in 1848) was too small and shallow for modern ships. It was also very polluted from city sewers and industries. In 1871, the old canal was deepened to try and reverse the river's flow. But this only worked for one season. The new, bigger Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was designed to solve both the pollution and shipping problems.

Building the Canal: A Huge Project

By 1887, engineers decided the best way to fix Chicago's water problem was to reverse the flow of the Chicago River. Engineer Isham Randolph noticed a low ridge about 12 miles from Lake Michigan. This ridge separated the Mississippi River's water system from the Great Lakes' system. Native Americans had known about this low spot for a long time. They used it as a portage, carrying their canoes between the Chicago River and the Des Plaines River.

The Illinois and Michigan Canal had already been cut through this ridge in the 1840s. The new plan was to cut through the ridge even deeper. This would send wastewater away from the lake, through the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers, all the way to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. In 1889, the Illinois General Assembly created the Sanitary District of Chicago (SDC) to make this plan happen.

Isham Randolph became the Chief Engineer for the SDC. He helped solve many problems during construction. One challenge was a strike by about 2,000 workers in 1893. They were protesting a wage cut. The strike caused some trouble, and the Governor even called in the Illinois National Guard. The strike was settled within two weeks.

The new Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal opened on January 2, 1900. It connected the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River at Lockport, Illinois. By January 17, the full flow of water was released. More construction from 1903 to 1907 extended the canal to Joliet, Illinois. This was done to fully replace the old Illinois and Michigan Canal. The amount of water flowing through the canal is controlled by the Lockport Powerhouse and other gates.

Building the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was the largest earth-moving project in North America at that time. It also helped train many engineers. These engineers later used their skills to build the Panama Canal. In 1989, the Sanitary District of Chicago was renamed the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago.

Water Diversion from the Great Lakes

The Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal works by taking water from Lake Michigan and sending it into the Mississippi River system. When the canal was built, the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) allowed a certain amount of water to be diverted. However, over the years, this limit was not always followed.

While more water helped flush out sewage, it also affected the water levels of the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River. This led to legal battles. States downstream of the canal supported the diversion, while states upstream of Lake Michigan and Canada opposed it. The Supreme Court made decisions about this in 1925 and 1929.

In 1930, the USACE took over managing the canal. They reduced the amount of water taken from Lake Michigan but kept the canal open for ships. This pushed the sanitary district to improve how they treated sewage. Today, how much water is taken from the Great Lakes is managed by an international agreement with Canada and by the governors of the Great Lakes states.

Pollution in the Canals

Even today, Chicago's sewage treatment system doesn't fully clean the water before it goes into the canals. Unlike many other big American cities, Chicago doesn't use a final cleaning step with chlorine. This means the canal water still contains bacteria. Signs along the canals warn people that the water is not safe for "any human body contact."

Asian Carp and the Canal

A big concern for the canal is the presence of Asian carp. These fish were brought to the U.S. in the 1970s to help clean algae from catfish farms. But they escaped! They have spread through the Mississippi River system. People worry they could get into the Great Lakes through the canal. Asian carp, especially the silver carp (also called "flying carp"), eat a lot of the food that native fish need. This can harm the natural fish populations.

In November 2009, scientists found DNA from Asian carp above an electric barrier in the canal. This barrier was built to stop the carp from moving into the Great Lakes. In December 2009, the canal was closed. Officials used a fish poison called rotenone to try and kill Asian carp north of Lockport. They found only one carp during this effort.

In December 2009, Michigan's Attorney General filed a lawsuit with the Supreme Court. He wanted the canal closed immediately to keep Asian carp out of Lake Michigan. Illinois and the Army Corps of Engineers were named in the lawsuit.

Illinois argued that closing the canal would stop millions of tons of important shipments. This includes things like iron ore, coal, and grain, worth over $1.5 billion a year. It could also cause many people to lose their jobs. However, Michigan and other Great Lakes states argued that the fishing and tourism industries in the Great Lakes are worth $7 billion a year. They said these industries would be badly hurt if Asian carp got into the lakes.

In January 2010, the Supreme Court did not agree to close the canal right away. In August 2011, another court also rejected the request to close it.

|

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |