Chicano Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chicano Park |

|

|---|---|

| Parque Chicano (Spanish) | |

The Chicano Park kiosko, designed by architect Alfredo Larín.

|

|

| Location | Logan Heights, San Diego, California |

| Area | 7.9 acres (32,000 m2) |

| Created | April 22, 1970 |

| Operated by | Chicano Park Steering Committee |

|

Chicano Park

|

|

| NRHP reference No. | 12001192 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 23, 2013 |

| Designated NHL | December 23, 2016 |

Chicano Park (in Spanish: El Parque Chicano) is a special park in Barrio Logan, a neighborhood in central San Diego, California. This area is home to many Chicano and Mexican American families. The park covers about 7.9 acres (32,000 square meters).

It is located right under the San Diego–Coronado Bridge. The park is famous for having the largest collection of outdoor murals in the United States. It also features sculptures, earthworks, and a unique building called a kiosko. All these artworks celebrate the community's rich cultural heritage.

Chicano Park became an official historic site in San Diego in 1980. Its murals were recognized as important public art in 1987. Because of its connection to the Chicano Movement, the park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. It was then named a National Historic Landmark in 2016.

Like Berkeley's People's Park, Chicano Park was created after people took over the land in a peaceful way. Every year on April 22, or the closest Saturday, the community celebrates this day. It's called Chicano Park Day.

Contents

History of Chicano Park

How the Park Started

The area was first called the East End. In 1905, it was renamed Logan Heights. The first Mexican families moved there in the 1890s. More people came after 1910, escaping the Mexican Revolution. So many Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans settled there that the southern part became known as Barrio Logan.

The neighborhood used to reach all the way to San Diego Bay. Residents could easily get to the waterfront. But this changed during World War II. Naval bases blocked access to the beach, which made the community upset.

This feeling grew in the 1950s. The area was changed to allow both homes and factories. Junk yards and repair shops moved into the neighborhood. This caused air pollution, loud noise, and made the area less pleasant for living. The community felt even more ignored when Interstate 5 cut through the barrio in 1963. Then, in 1969, the elevated ramps for the San Diego–Coronado Bridge divided it further.

At that time, Mexican-Americans were often left out of decisions about their communities. They felt their leaders didn't represent them. So, they didn't make formal complaints at first. But this started to change with the Civil Rights Movement. As different community efforts came together under the Chicano Movement, people in Barrio Logan became more aware of their rights. They also felt more powerful.

The Chicano Movement worked to support Mexican-American rights. This included the right to organize and bargain for better working conditions. Leaders like César Chávez and Dolores Huerta of the United Farm Workers fought for these rights. Other groups worked for equal education and for the rights promised to Mexicans under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. They also wanted recognition for Mexican-American history and culture.

Community residents had been asking for a park for a long time. The City Council had promised to build one. This was to make up for losing over 5,000 homes and businesses. These were removed to build the freeway and bridge. The overhead freeways, with their many gray concrete pillars, also made the area look worse. In June 1969, the park was officially approved, and a spot was chosen. But nothing was done to start building it.

The Community Takes Action

The community's patience ran out on April 22, 1970. Mario Solis, a student and Brown Beret member, was on his way to school. He noticed bulldozers near the area chosen for the park. He asked what was happening. He was surprised to learn they were building a parking lot for a California Highway Patrol station, not a park.

Mario Solis quickly went door-to-door to share the news. At school, he told students in Professor Gil Robledo's Chicano studies class. They printed flyers to get more attention. At noon that day, Mexican-American high school students walked out of their classes. They joined other neighbors who were already at the site. Some protesters linked arms around the bulldozers. Others planted trees, flowers, and cactus. Mario Solis reportedly used a bulldozer to flatten the land for planting. The flag of Aztlán was also raised on an old telephone pole. This was a symbol of reclaiming land that was once part of Mexico.

Many young people and families joined the protest. When the crowd grew to 250 people, construction was stopped. The community stayed at Chicano Park for twelve days. During this time, community members and city officials met to discuss creating the park. Groups from Los Angeles and Santa Barbara came to support the occupation. The Chicano Park Steering Committee was formed by Josephine Talamantez, Victor Ochoa, Jose Gomez, and others.

The community didn't fully trust the city. They feared that leaving the land would mean giving up. An agreement was finally reached. The Steering Committee asked people to end the occupation but kept informal picketers on the sidewalks. These picketers shared information about the project. They warned that the park would be re-occupied if talks failed.

At a meeting on April 23, a young artist named Salvador Torres shared his idea. He had just returned to the barrio from art school. He imagined decorating the freeway pillars with beautiful artworks. He also wanted a green area with trees and plants that would reach the waterfront. Because of this vision, he is sometimes called "the architect of the dream." Finally, on July 1, 1970, about $21,815 was set aside to develop 1.8 acres of land for the park.

Building the Park and Murals

The park's creation began on the day of the takeover. The occupiers made small improvements to the land. But the famous murals didn't start until 1973. However, artists like Guillermo Aranda, Mario Acevedo, Victor Ochoa, and Tomas Castaneda began adding unplanned murals and colors to the freeway walls and pillars in 1970.

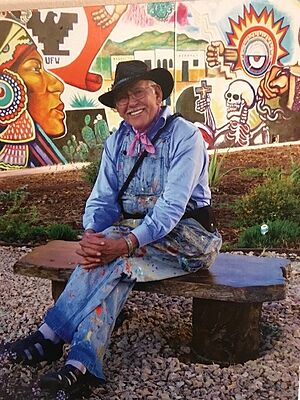

Most artists and their groups raised money themselves. They bought acid to clean the columns, conditioner to prepare them, and paints. Victor Ochoa, a founding member of the Chicano Park Steering Committee, remembers a big painting event on March 23, 1973. He brought 300 brushes, and nearly 300 people helped paint that weekend. The Centro Cultural de la Raza in San Diego's Balboa Park helped train many of the muralists. Many non-Chicanos, like Anglo artist Michael Schnorr, also took part. Eventually, about 16 artists dedicated themselves to finishing the murals. Many well-known Chicano artists and groups, such as members of the Royal Chicano Air Force, participated. Over time, more plants were added to create a cactus garden.

The first group of murals took almost two years to finish. The murals at Chicano Park tell the history and culture of Mexican-Americans and Chicanos. They cover many topics, including immigration, women's rights, and feature historical and civil rights leaders.

In 1978, there was a "Mural Marathon" from April 1 to April 22. During those 21 days, artists painted about 10,000 square feet of murals.

Other additions to the park happened bit by bit. The artists' big "Master Plan" was never fully adopted by the city. The park has grown and now almost reaches "all the way to the bay." This phrase was a rallying cry in a 1980 campaign to expand the park. The Cesar E. Chávez Waterfront Park was started in 1987 and finished in 1990. This finally gave the community access to the beach again. Except for three city blocks not part of the park, the original goal of a community park with waterfront access has been achieved.

In the mid-1990s, Caltrans decided to make the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge safer for earthquakes. The community worried the murals would be damaged. They worked to stop the project to protect the art. They felt officials didn't understand the history and culture the murals represented. A solution was found: the murals would be covered with plywood to protect them during the work. Afterward, they would be restored.

Recent Times

In 2003, a plan to fix up the park was delayed. This happened because Caltrans didn't like the word "Aztlán," which had been spelled out in rocks on the park grounds for years. They called the term "militant," meaning it was seen as aggressive. They claimed using federal money for the project would go against the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This act prevents showing favoritism to certain groups.

However, after talking with civil rights experts, Caltrans decided the word did not break the law. The $600,000 grant was then allowed to go through. Aztlan is believed to be the ancient homeland of the Aztecs. Historians have wondered where Aztlán might have been. Some think it includes the lands the United States took from Mexico in the Mexican-American War (the Southwestern United States). This is how Chicanos, and some murals at Chicano Park, identify it. Whether Aztlán was a real place or a mythical one is still debated. In the Plan Espiritual de Aztlan, a goal was stated to make this territory an independent Chicano nation.

Chicano Park was added to the list of National Historic Landmarks on December 23, 2016.

On September 3, 2017, a group called "Patriot Fire" organized a "Patriot Picnic" in the park. This was a protest against what they called "anti-American" murals. Over 500 community members and supporters gathered to block the center of the park. Police saw the crowd becoming a threat. They escorted the "Patriot Fire" group out of the park for their safety. On February 3, 2018, another "Patriot Picnic" was planned by a group called "Bordertown Patriots." They wanted to take down the Aztlán flag in the park and replace it with a U.S. flag. Many far-right figures tried to enter the park. But hundreds of Barrio Logan residents and supporters were already in the central area, preventing them from entering. Police directed the protesters to a special "free speech zone" in another part of the park to avoid a conflict. Four people were arrested during this protest.

Landmark Status

Because of the size and historical importance of its murals, Chicano Park was named an official historic site by the San Diego Historical Site Board in 1980. Its murals were officially recognized as public art in 1987. Josephine Talamantez and Manny Galaviz submitted the proposal that successfully added Chicano Park to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. This was due to its strong connection with the Chicano Movement.

In 1997, Josephine Talamantez started the process to get Chicano Park and its artwork listed on the National Register. Her goal was to prevent the city of San Diego from damaging the murals while fixing the Coronado Bridge. After many years of work, Chicano Park was officially named a National Historic Landmark in December 2016. Talamantez also helped open the Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center. It is located in a nearby city-owned building that used to be the Cesar Chavez Continuing Education Center.

Chicano Park Museum

The Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center in Logan Heights, San Diego, opened on October 8, 2022. Its first main exhibit was called "Stories of Resilience and Self-Determination." Like the park, the museum is a community space. It often works with other local non-profit groups.

Inside the museum, there is a gallery for local Chicano artists. They can show and sell their artwork there. The museum also has a main exhibit area, a room for historical records, a community room, and a gift shop. In the gift shop, visitors can look at or buy various art pieces made by local California artists.

The museum's first exhibition ran until September 9, 2023. It highlighted groups and ideas important to the Chicano Park Movement. These included: The Brown Berets, Centro Cultural de la Raza, the Chicano Park Steering Committee, Danza Azteca (Aztec dance), Danza Folklorica (folk dance), Kumeyaay Story, Lowriders, Música, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Teatro (theater), Unión del Barrio, and the Youth. The exhibition also featured an installation by the respected artist Salvador “Queso” Torres. The exhibits aim to teach people about "Chicana/o, Latina/o, and Indigenous culture and history."

Murals of Chicano Park

Projects to restore the murals began in 1984. The murals have been restored almost continuously since then. A large restoration project happened in 2012. Many of the original artists came back to work on the art. Twenty-three murals were restored. Artists like Victor Ochoa took part in the Chicano Park Mural Restoration Project, which lasted 13 months. Ochoa was well-known for helping organize local artists to paint murals at Chicano Park in the 1970s. He also edited a guide on how to restore the murals. The murals were fully restored by 2013, just in time for the park's 43rd Anniversary Celebration.

On June 25, 2023, a new mural was revealed in Barrio Logan. It honored a 1975 ruling by the Supreme Court of California that banned "el cortito." "El cortito" was a short-handled hoe that made many farm workers bend down for hours. This caused spinal problems later in life. This mural honors the hard work and sacrifices of those who worked in the fields. It shows images of farmworkers. The mural was created by artists Mario Chacon, Ariana Arroyo, and Gary Hartbur.

Events at the Park

Chicano Park hosts many different events and groups throughout the year. Various groups who practice and perform Aztec dance use Chicano Park to get ready for ceremonies and other events.

Every year around April 22, Chicano Park holds an anniversary celebration. This event celebrates the day the community took over the area. The park features traditional music as well as modern bands. Ballet folklorico (folk dance), lowrider car shows, and art workshops are also part of these celebrations.

- 40th Anniversary Theme: 40 Años de the Tierra Mia: Aquí Estamos y No Nos Vamos (40 Years of My Land: We Are Here and We Are Not Leaving)

- 43rd Anniversary Theme: Chicano Park: Aztlan's Jewel & National Chicano Treasure

- 44th Anniversary Theme: La Tierra Es De Quien La Trabaja: The Land Belongs To Those Who Work It...

See also

In Spanish: Parque Chicano para niños

In Spanish: Parque Chicano para niños

- List of parks in San Diego

- Carmen Linares-Kalo

- Chicano murals

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |