Chilocco Indian Agricultural School facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School

|

|

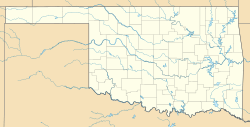

One of the abandoned buildings at Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, a school for Native Americans that operated from 1884 to 1980 located approximately 20 miles north of Ponca City, Oklahoma.

|

|

| Location | US 77 and E0018 Rd., Newkirk, Oklahoma |

|---|---|

| Area | 288 acres (117 ha) |

| Architect | Bidwell, Edmund; Pauley, Hoyland & Smith |

| Architectural style | Romanesque, Colonial Revival, et al. |

| NRHP reference No. | 06000792 |

| Added to NRHP | September 08, 2006 |

Chilocco Indian School was a special school for Native American students. It focused on agricultural training. The school was located on reserved land in north-central Oklahoma. It operated for many years, from 1884 until 1980.

Chilocco was about 20 miles north of Ponca City, Oklahoma. It was also seven miles north of Newkirk, Oklahoma, close to the Kansas border. The name "Chilocco" comes from the Creek word tci lako. This word meant "big deer" but often referred to a horse.

In the early 1900s, there was a legal case about whether the Chilocco land was part of Kay County. The U.S. Supreme Court decided that the school land was not an "Indian Reservation" in the usual sense. This meant the school was considered separate from traditional Indian Territory.

Contents

Why Chilocco School Was Created

In 1882, the U.S. Congress decided to create five special boarding schools for Native American children. These schools were not located on reservations. Chilocco was one of these five schools.

Other similar schools included Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas. Major James M. Haworth, who was the first Superintendent of Indian Schools, chose the spot for Chilocco. President James Garfield officially approved the school's establishment.

Chilocco was built in an area known as the Cherokee Outlet. The Cherokee Nation provided a large amount of land, about 8,640 acres (35 square kilometers). This land helped Chilocco carry out its main goal of teaching farming skills.

What Students Learned at Chilocco

Chilocco Indian School offered both regular school subjects and vocational education (job skills training). Students came from many different Native American tribes across the United States. The main goal of the school was to help Native American students learn skills for life in the wider American society.

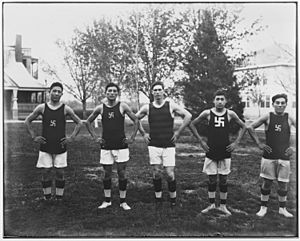

Until the 1930s, the school had a very structured and disciplined environment. Students wore special uniforms and followed a strict daily schedule. Some students found the conditions challenging, with simple meals and limited personal attention.

The school focused mostly on teaching job skills rather than academic subjects. Students were required to do manual labor and domestic chores. This was called "actual work" and helped maintain the school. For girls, the training often prepared them for jobs in other homes or at boarding schools. Students also had to attend Christian religious services once a week.

In 1928, a report criticized how Indian boarding schools were run. This led to some changes at Chilocco in the 1930s. Boys and girls were allowed to sit together during meals. More attention was given to academic studies. The amount of daily work students had to do for school upkeep was also reduced.

The school's curriculum included many agricultural trades, like horseshoeing and blacksmithing. It also taught building trades, printing, shoe repair, tailoring, and leather work. In later years, students could learn plumbing, electrical work, welding, auto mechanics, food services, and office skills.

Chilocco's History and Growth

Chilocco School first opened its doors in 1884 with 150 students. These first students came from tribes like the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Wichita, Comanche, and Pawnee. The first class graduated in 1894, with 15 students earning their diplomas.

As the school grew, more buildings were added over the years. By one point, the school had over 100 buildings. These included a large dining hall and a hospital. Many buildings were made from a unique yellow limestone found nearby. Students sometimes helped by breaking large rocks into smaller pieces for construction.

Student numbers went down in the 1920s, and the elementary school section closed. However, during the Great Depression in 1929, more students enrolled. This was because many Native American families faced hardship, and Chilocco offered education, food, clothing, and shelter. One graduate said, "It meant we were educated, clothed, fed, and had a roof over our head."

In 1949, a special program for Navajo youth began. Enrollment at Chilocco reached its highest point in the 1950s, with about 1,300 students. After that, enrollment slowly dropped. More Native American students could attend public schools, so a boarding school was no longer as necessary.

In the 1970s, some Native American groups raised concerns about conditions at the school. By the late 1970s, only about 100 students remained at Chilocco.

After Chilocco Closed

Chilocco Indian School officially closed on June 3, 1980. This happened because the U.S. Congress stopped providing money for it. The school's superintendent wrote in the 1980 yearbook that Chilocco was "another in a long list of broken promises."

During its history, nearly 18,000 students from 126 different Native American tribes attended Chilocco. A total of 5,542 students earned high school diplomas. Many graduates were from the Cherokee, Choctaw, Navajo, and Creek tribes.

After the school closed, its land was given to five local tribes. These tribes formed the Chilocco Development Authority. The tribes involved were the Kaw Nation, the Otoe-Missouria Tribe, the Pawnee Nation, the Ponca Nation, and the Tonkawa Tribe. The Cherokee Nation also holds a share of the mineral rights to the land.

From 1989 to 2001, a rehabilitation center used the property. In 2000, the Council of Confederate Chilocco Tribes was formed. This group of tribes works together to manage the former school campus.

In 2006, Chilocco Indian Agricultural School was added to the National Register of Historic Places. This recognizes its importance in history.

In 2011, the Chilocco campus was closed to the public. It began to be used as a training area for federal law enforcement officers.

In 2016, the Cherokees announced plans to lease over 4,000 acres of Chilocco land for a wind energy project. Other parts of the land continued to be used for ranching.

In 2017, the Department of Homeland Security announced they would conduct tests at Chilocco. These tests involved releasing harmless particles onto buildings. The goal was to see how well certain agents might enter homes. The Council of Confederate Chilocco Tribes gave permission for these tests.

In 2021, after discoveries at Canadian residential schools, the Chilocco Alumni Association asked for a search for unmarked graves outside the school's cemetery.

Famous Chilocco Alumni

Many notable people attended Chilocco Indian School:

- Ernest Childers – A Medal of Honor recipient from World War II, a Creek tribal member.

- Woody Crumbo – A famous artist, from the Potawatomi tribe.

- William Henry "Lone Star" Dietz – A football player and coach, from the Sioux tribe.

- Durbin Feeling – A Cherokee linguist, known for his work with the Cherokee language.

- Charles George – A Medal of Honor recipient from the Korean War, a Cherokee tribal member.

- Marlene Riding In-Mameah – A skilled silversmith, from the Pawnee tribe.

- Jack C. Montgomery – A Medal of Honor recipient from World War II, a Cherokee tribal member.

- Bertha Shipley – The first Navajo student to graduate from Chilocco in 1915.

- Wes Studi – A well-known actor, from the Cherokee tribe.

- Johnny Tiger Jr. – An artist.

- Moses J. Yellow Horse – A professional baseball pitcher, from the Pawnee tribe.

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |