Christopher Smart facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Christopher Smart

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 11 April 1722 Shipbourne, England |

| Died | 20 May 1771 (aged 49) King's Bench Prison, London |

| Pen name | Mrs Mary Midnight, Ebenezer Pentweazle |

| Occupation | Actor, Editor, Playwright, Poet, Translator |

| Literary movement | The Augustans |

| Spouse |

Anna Maria Carnan

(m. 1752) |

| Children | 3; including Elizabeth |

Christopher Smart (born April 11, 1722 – died May 20, 1771) was an English poet. He wrote for popular magazines like The Midwife and The Student. He was also friends with famous people such as Samuel Johnson and Henry Fielding. Smart was well-known in London.

Smart was famous for using the funny pen name "Mrs. Mary Midnight." Many people also knew that his father-in-law, John Newbery, had him stay in a hospital for people with mental health issues. This happened because of Smart's strong religious beliefs. Even after he was released, he had a difficult reputation. He often owed more money than he could pay back. This led to him being held in a prison for people who couldn't pay their debts, where he stayed until he died.

His two most famous works are A Song to David and Jubilate Agno. People think he wrote these while he was in St. Luke's Asylum. However, no one knows for sure when he wrote them. Jubilate Agno was not even published until 1939, when it was found in a library. A Song to David got mixed reviews at first. During his lifetime, Smart was mostly known for his writings in The Midwife and The Student. He was also known for his "Seaton Prize poems" and his funny poem The Hilliad. While he is mostly seen as a religious poet, his poems also covered other topics. These included his ideas about nature and his support for English nationalism.

Contents

Who Was Christopher Smart?

His Early Life

Christopher Smart was born in Shipbourne, Kent, England, on April 11, 1722. He was born on the Fairlawne estate, which belonged to William Vane, 1st Viscount Vane. His nephew said he was "of a delicate constitution," meaning he was a bit fragile. He was baptized on May 11, 1722. His father, Peter Smart, worked as a manager for the estate. His mother, Winifred, was from Wales. Christopher had two older sisters, Margaret and Mary Anne.

When he was young, Christopher Vane, 1st Baron Barnard and Lady Barnard lived at Fairlawne. Lady Barnard left Smart £200 in her will. This was likely because his father was close to the Vane family. Christopher was even named after Christopher Vane. In 1726, after Christopher Vane died, Peter Smart bought Hall-Place in East Barming. This property included a house, fields, orchards, and woods. It was important in Smart's later life. From age four to eleven, he spent a lot of time around the farms. Some people think he had asthma attacks, but not everyone agrees he was a "sickly youth." The only story from his childhood is a short poem he wrote at age four. In it, he challenged another boy for the attention of a twelve-year-old girl.

While at Hall-Place, Smart went to Maidstone Grammar School. His teacher, Charles Walwyn, was a scholar from Eton College. Smart learned a lot about Latin and Greek there. He did not finish school in Maidstone because his father died on February 3, 1733. His mother then moved Christopher and his sisters to live near relatives in Durham. She had to sell much of their property to pay off his father's debts.

Smart then went to Durham School. It is not known if he lived with his uncle or a teacher. He spent holidays at Raby Castle, owned by Henry Vane, 1st Earl of Darlington. Henry Vane's children were close in age to Smart. Anne Vane was traditionally described as his "first love." Smart wrote many poems for Henrietta, the Duchess of Cleveland, who was also part of the Vane family. Because of his closeness to the Vane family and his learning skills, Henrietta gave him £40 a year. Her husband continued this after her death in 1742. This money allowed Smart to attend Pembroke College, Cambridge.

College Days

Smart started at Pembroke College on October 20, 1739. He was a "sizar," meaning he sometimes had to do small jobs like serving meals. On July 12, 1740, he received a scholarship that paid him six pounds a year. He also got four pounds a year for his studies. Even though he did well in school, he started to get into debt. He spent a lot of money on a fancy lifestyle.

At Pembroke, Smart borrowed many books about literature, religion, and science. These books helped him write poems for the "Tripos Verse" at the end of each year. These Latin poems, along with his Latin translation of Alexander Pope's Ode on St. Cecilia's Day, helped him win the Craven scholarship. This scholarship paid £25 a year for 14 years. With these scholarships and becoming a "fellow" in 1743, Smart could call himself a "Scholar of the University."

In 1743, Smart published his translation of Pope's Ode on St. Cecilia's Day. He paid for it himself. He wanted to impress Pope and translate Pope's Essay on Man. But Pope suggested he translate An Essay on Criticism instead. Smart treasured the letter Pope sent him. To honor this, the Pembroke Fellows had a portrait painted of Smart holding Pope's letter. They also let him write a poem for Pembroke's 400th anniversary in 1744.

In October 1745, Smart was chosen as a philosophy teacher and a keeper of the college's money. The next year, he became a Master of Arts. He was again chosen for these roles. However, he had run up debts of more than twice his yearly income. So, in 1747, he was not re-elected to these positions. But he was made a "Preacher before the Mayor of Cambridge." This suggests he became a priest in the Anglican church.

In 1746, Smart became a tutor to John Delaval, 1st Baron Delaval. But this job ended quickly because Delaval broke many rules. Smart then went back to studying. In April 1747, a play he wrote, A Trip to Cambridge, was performed at Pembroke College Hall. Smart played many parts, including female roles. The play was very popular.

In his last years at Pembroke, Smart wrote and published many poems. In 1748, he planned to publish a collection of his poems. This collection, called Poems on Several Occasions, was finally printed in 1752.

Around 1749, Smart fell in love with Harriot Pratt. He wrote many poems about her. But by 1752, he wrote a poem called "The Lass with the Golden Locks" that suggested he was done with Harriot and other women. The "lass with the golden locks" was Anna Maria Carnan, who would become his wife. She was the stepdaughter of John Newbery, who would become Smart's publisher.

Life in London

Smart slowly left college life for London. By 1750, he was living near St. James's Park and getting to know the writing world of Grub Street. This year, he started working with John Newbery. He worked for Newbery and married his stepdaughter, Anna, in 1752. Smart's daughter said that Charles Burney introduced them. Newbery was looking for writers for his magazines, The Midwife and The Student. Smart had won Cambridge's "Seatonian Prize" on March 25, 1750, which likely caught Newbery's attention.

The "Seatonian Prize" was a yearly contest for an English poem about "the Perfections or Attributes of the Supreme Being" (God). Smart won in 1750 with his poem On the Eternity of the Supreme Being. The prize was worth £17 a year. After his poem was published, Smart became a regular writer for The Student magazine.

Before Smart joined, The Student was a serious magazine. But once he started writing for it under many fake names, it became full of jokes and funny essays. He wrote most of the poems and 15 essays for the magazine. He also added funny news reports called The Inspector. These reports promoted Smart's works and included stories by his friends, like Henry Fielding, Samuel Johnson, William Collins, and Tobias Smollett.

While in London, Smart also created Mother Midnight's Oratory. These were "wild tavern entertainments" where Smart wrote and performed.

The Midwife Magazine

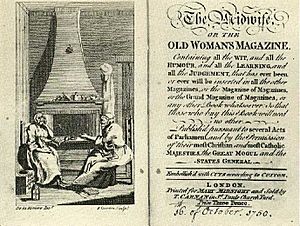

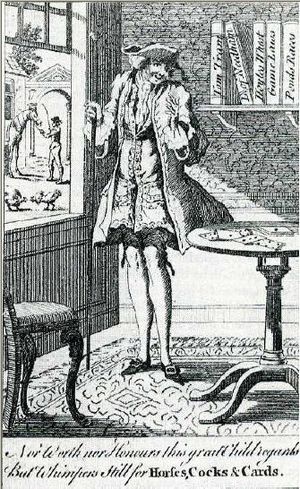

The Midwife magazine was mainly produced by Smart. It was first published on October 16, 1751, and ran until April 1753. It was so popular that it had four editions. To keep his identity a secret, Smart pretended to be a midwife, using the name "Mrs. Mary Midnight."

When his poem "Night Piece" was criticized, Smart used The Midwife to respond. He even promised to write a poem against his critic. This argument lasted for a few issues of The Midwife. But it ended when Smart focused on writing for a play and promoting it in the magazine.

Smart's focus slowly moved away from The Midwife when he won the "Seatonian Prize" again. He also started working on Newbery's children's magazine, The Lilliputian Magazine. However, Smart fully returned to his Mrs. Midnight character in December 1751. He started The Old Woman's Oratory, a show where he played Mrs. Midnight. It included songs, dances, and animal acts. The show was successful. But not everyone liked it. Horace Walpole called it "the lowest buffoonery." In late 1752, Smart published a collection of his works called Poems on Several Occasions. This led to the end of the Oratory and The Midwife.

Later Career and Challenges

In 1752, Christopher Smart became part of a "paper war" among London writers. After his book Poems on Several Occasions was published, a writer named John Hill strongly criticized Smart's poetry. Smart responded with his funny poem The Hilliad. This argument between writers may have been just for publicity. Smart's Hilliad was a very strong attack in this "war."

Smart was getting into a lot of debt. He started publishing as much as he could to support his family. He married Anna-Maria Carnan around 1752 or 1753. They kept their marriage a secret so Smart could keep getting money from his Cambridge scholarship. By 1754, they had two daughters, Marianne and Elizabeth Anne. Once his marriage was known, he could no longer get money from Pembroke College. Newbery let Smart, his wife, and children live at Canonbury House. Newbery was known for being kind, but he liked to control his writers. This likely caused problems between them by 1753.

Between 1753 and 1755, Smart published or republished at least 79 works. But even with money from these, it was not enough to support his family. He wrote a poem each year for the "Seatonian Prize," but this was only a small part of his writing. He had to do a lot of "hack work," which meant writing quickly for publishers to earn money. In December 1755, he finished The Works of Horace, Translated Literally into English Prose. This translation of Horace was widely used but didn't make him much money.

In November 1755, he signed a long contract to write a weekly paper called The Universal Visitor or Monthly Memorialist. But the stress of publishing made Smart unwell, and he couldn't keep up. Friends like Samuel Johnson helped him by writing for the magazine. In March 1756, Newbery published Smart's last "Seatonian Prize" poem, On the Goodness of the Supreme Being, without his permission. Later, on June 5, Newbery also published Smart's Hymn to the Supreme Being, again without permission. This poem thanked God for recovering from an illness, possibly a mental health issue. This hymn marks the time when Smart's mental health struggles began to improve. It also shows the start of his strong focus on religion and constant prayer.

His Time in the Asylum

Smart was admitted to St Luke's Hospital for Lunatics, a hospital for people with mental health issues, on May 6, 1757. Some believe Newbery had him confined because of old debts and a bad relationship. Newbery had even made fun of Smart in one of his books. However, there is also a story that Smart started praying loudly in public in St. James's Park, which caused people to leave.

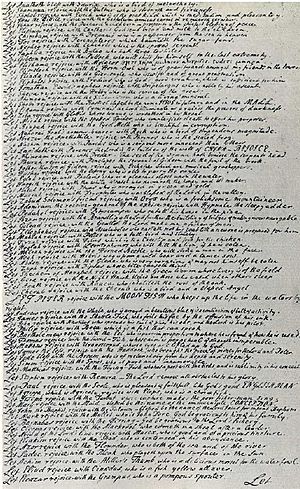

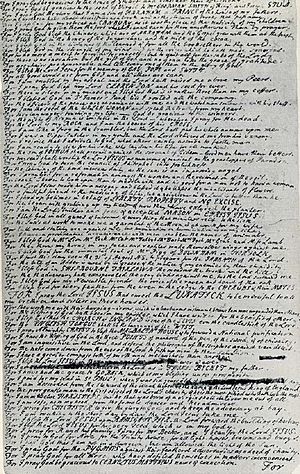

We don't know exactly what happened during his time there. But Smart did work on two of his most famous poems, Jubilate Agno and A Song to David. He may have been in a private hospital before St. Luke's. He was later moved from St. Luke's to another hospital for financial reasons. While he was there, his wife Anna left and took their children to Ireland. Being alone led him to write religious poetry. He stopped using the usual poetry styles of his time when he wrote Jubilate Agno. His poems from this time show a strong desire for a direct connection with God. He believed in an "inner light" that connected him to God.

Smart was left alone, except for his cat Jeoffrey and occasional visitors. He likely felt "homeless" and "in between public and private space." In London, only a few of his works were still published. Not everyone saw Smart's mental health struggles as a problem. Samuel Johnson often defended him. A century later, Robert Browning said that A Song to David was great because Smart was struggling, and that the poem made him as good as famous poets like Milton and Keats.

He was released from St. Luke's hospital after one year. People thought he was confined elsewhere for the next seven years, during which he wrote Jubilate Agno. His daughter, Elizabeth, said that friends invited him to dinner after he got better, and he never returned to confinement. Smart left the hospital on January 30, 1763.

Later Years and Legacy

A Song to David was printed on April 6, 1763, along with a plan for a new translation of the Psalms. People say Smart wrote the poem during his second time in a hospital for mental health issues. The poem was not well-received at first. This might have been because of personal attacks against Smart for being released from the hospital. However, Kenrick, Smart's old rival, praised the poem. Other writers also wrote poems praising Smart's work. Smart responded to his critics, and they said they would "say no more of Mr. Smart."

After A Song to David, Smart tried to publish his translations of the Psalms. Newbery tried to stop him by hiring another writer, James Merrick, to do his own translations. Newbery then hired Smart's new publisher, which forced Smart to find another publisher. This delayed the printing of his Psalms. Finally, on August 12, 1765, he printed A Translation of the Psalms of David. This book also included Hymns and Spiritual Songs and a second edition of A Song to David. This work was criticized, and Newbery's version by Merrick was often compared to Smart's. However, today, Smart's version is seen more positively. While working on this, he also translated the Phaedrus and a verse translation of Horace. His verse Horace was published in July 1767. It included a preface where he criticized Newbery, but Newbery died soon after.

On April 20, 1770, Smart was arrested for debt. On January 11, 1771, he was sent to the King's Bench Prison. Even though he was in prison, Charles Burney bought him some freedom. Smart's last weeks might have been peaceful, though sad. In his last letter, Smart asked for money, saying he was recovering from an illness and had nothing to eat. On May 20, 1771, Smart died from liver failure or pneumonia. This was shortly after he finished his last work, Hymns, for the Amusement of Children.

Death

Christopher Hunter, Smart's nephew, wrote after his uncle's death, "I trust he is now at peace; it was not his portion here."

On May 22, 1771, a group of twelve other prisoners declared that Smart "died a Natural Death within the Rules of the Prison." He was buried on May 26 in St Paul's Covent Garden.

What Did He Write About?

Christopher Smart's works were not widely studied until Jubilate Agno was found in 1939. Many recent experts look at Smart's work from a religious point of view. Others use psychology to understand his writings.

Religion in His Poetry

Smart's early religious poems were different from his later, more intense ones. In his first "Seatonian Prize" poem, On the Eternity of the Supreme Being, he combined traditional religious poetry with more personal thoughts. He believed that all of creation constantly praises God. A poet's job, he thought, was to "give voice to mute nature's praise of God."

Jubilate Agno shows Smart moving away from traditional poetry styles. He explored complex religious ideas. His "Let" verses connect all of creation, almost like his own version of the Bible. Smart played with words and their meanings to connect with the divine power in language. The original manuscript had "Let" and "For" verses on opposite pages. But experts found that they were meant to be read together. The "For" verses are more personal, while the "Let" verses are about public matters.

Smart believed that words and language connect poets to God. He saw God as the "great poet" who used language to create the universe. Smart tried to capture this creative power in his words. He also believed that every part of nature is alive because it is connected to God. He criticized scientists who described nature in a cold way, ignoring God's glory.

Smart's A Song to David tries to connect human poetry with Bible poetry. The Biblical David is important in this poem. In Jubilate Agno, David represents the creative power of poetry. But in A Song to David, he becomes a perfect example of a religious poet. By focusing on David, Smart could use "heavenly language." Many experts have looked at David's role as the planner of Solomon's Temple and his possible connection to the Freemasons. The poem's true power comes when Christ is introduced. The final parts of the poem, according to Neil Curry, show a "final rush for glory."

Smart's Psalms and Hymns tried to make the Old Testament more Christian. They also allowed Smart to relate to David's suffering. He used them to strengthen his own religious beliefs. In Smart's "Christianizing" of the Psalms, Jesus becomes a divine example of suffering. Smart and David both praise God for Jesus's sacrifice and for the beauty of creation. The Hymns and Psalms create their own kind of worship. They try to change Anglican worship by showing God's place in nature.

Smart's Hymns also show English patriotism and England's special favor from God. They express a "delight in creation" that other hymn writers of his time did not often show. His second set of hymns, Hymns for the Amusement of Children, was for younger readers. But Smart cared more about teaching children to be good than just being innocent. These works were sometimes seen as too complex for "amusement" because they had difficult ideas. They were meant to teach children specific good qualities. Like these hymns, Smart's The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ also taught morals. He changed the original Bible stories to make them simpler and easier to understand.

His Use of Language

Smart's use of language in Jubilate Agno is very important. Some experts believe he tried to connect to an "Ur language," a very old, original language. This would allow him to connect to "the Word calling forth the world." This is like how David and Orpheus could create things through their songs. Smart tried to create a poetic language that would connect him to "the one true, eternal poem." This language was related to Adam's "onomathetic" tradition. This is the idea that names have great power, and Adam could join in creation by naming things.

In Jubilate Agno, he said his writing created "impressions." He used puns and sounds that imitate what they describe (onomatopoeia). This helped him show the religious meaning of his poetic language. He also repeated words and referred to traditional works and the Bible for authority, especially in his Hymns. He used prophetic language to get his audience's attention.

In the 18th century, there was a debate about poetic language. Smart's translations, especially of Horace, showed that he wanted to bring back traditional forms of language. He believed language was important. He constantly revised his poems to make them better. Many of Smart's poems had two purposes. When they were set to music, they were changed to fit the music. By always revising, he made sure his poems were always the "authentic" version.

His View on Gender

Smarts role as Mrs. Midnight and his comments on gender in Jubilate Agno help us understand his views. As Mrs. Midnight, Smart challenged the usual social rules of 18th-century England. Some experts think the Mrs. Midnight character shows that Smart felt split between male and female roles. Others believe Mrs. Midnight proves that Smart saw a female connection to poetry. This character helped him use humor to talk about social issues.

Nature and the Environment

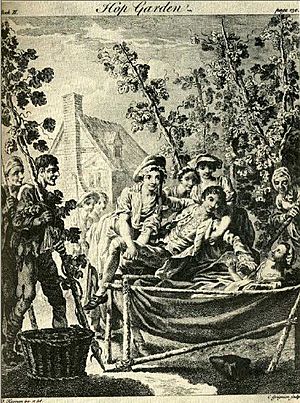

Smart was known as a "dedicated gardener." His poem The Hop-Garden helped this reputation. Even in the hospital, he convinced others of his connection to nature. Samuel Johnson saw Smart in the hospital and said, "he digs in the garden." For Smart, gardening was a way for humans to interact with nature and even "improve" it.

Smart wrote about more than just gardens. His focus on his cat Jeoffry is well-known. His interest in nature connects him to those who were mistreated in 18th-century society. The first part of Jubilate Agno is like a poetic "Ark." It pairs humans with animals to make all of creation pure. The whole work uses his deep knowledge of plants and how to classify them. He used the classification systems of Carl Linnaeus. However, Smart also added old myths from Pliny the Elder to his view of nature.

By using this knowledge, Smart gave a "voice" to nature. He believed that nature, like his cat Jeoffry, always praises God. But it needed a poet to bring out that voice. So, in Jubilate Agno, themes of animals and language are combined. Jeoffry becomes a symbol of the power of poetry.

Freemasonry

Many experts have looked at David's role as the planner of Solomon's Temple and his possible connection to the Freemasons. It is not known for sure if Smart was a Freemason. But there is evidence that he knew a lot about their beliefs. He admitted to writing for A Defence of Freemasonry. There are also stories of him attending Masonic meetings. This has led some to believe he was involved with Freemasonry. However, other experts say that since his name is not in their records, it is unlikely he was a member.

Smart's connection to Masonry can be seen in his poems, like Jubilate Agno and A Song to David. He often refers to Masonic ideas and praises Freemasonry. In Jubilate Agno, Smart writes, "I am the Lord's builder and free and accepted MASON in CHRIST JESUS." This line suggests a connection to a Christian version of Masonry. He also calls himself "the Lord's builder," linking his life to the building of King Solomon's Temple, which is an important Masonic idea. In A Song to David, Smart returns to the building of Solomon's Temple and uses many Masonic images.

This detail encouraged many experts to try to understand the "seven pillar" section of A Song to David using Masonic ideas. The poem follows two movements common in Freemason writing, like Jacob's Ladder: moving from earth to heaven and from heaven to earth. This image connects to Freemason beliefs about David and Solomon's Temple.

Based on this idea, the first pillar, the Greek letter alpha, represents the mason's compass and "God as the Architect of the Universe." The second, gamma, represents the mason's square. The third, eta, represents Jacob's ladder. The fourth, theta, is "the all-seeing eye." The fifth, iota, represents a pillar and the temple. The sixth, sigma, is an incomplete hexagram, known to Freemasons as "the blazing star." The last, omega, represents a lyre and David as a poet.

His Famous Works

Christopher Smart published many works during his life. Here are some of his most famous and important publications:

- A Song to David

- Poems on Several Occasions (which included The Hop-Garden)

- The Hilliad

- The Hop-Garden

- Hymns and Spiritual Songs

- Epistle to Mrs. Tyler

- Psalm 58

- Psalm 114

- On A Lady Throwing Snow-Balls At Her Lover

- For I Will Consider My Cat Jeoffry

- On My Wife's Birth-Day

- The Sweets Of Evening

- Where's The Poker?

- The Pig

- The Long-Nosed Fair

- Hymns for the Amusement of Children

- The Oratorios Hannah and Abimelech

- The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ

- A Poetical Translation of the Fables of Phaedrus

- The "Seatonian Prize" poems

- A Translation of the Psalms of David

- The Works of Horace Prose and Verse

One of his most famous poems, Jubilate Agno, was not published until 1939. This was done by William Force Stead. In 1943, parts of this poem were set to music by Benjamin Britten with the translated title Rejoice in the Lamb.

Smart is also believed to have written A Defence of Freemasonry (1765). This book responded to another work called Ahiman Rezon. Even though Smart's name is not on the title page, it has been known as his work since it was published. It includes a poem directly written by him.

A two-volume collection called Complete Poems of Christopher Smart was published in 1949. Penguin also published Selected Poems in 1990.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Christopher Smart para niños

In Spanish: Christopher Smart para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |