Augustan literature facts for kids

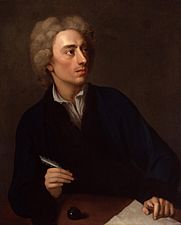

Augustan literature is a special style of British literature from the first half of the 18th century. It happened during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II. This period ended around the 1740s, with the deaths of famous writers like Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.

This time was important for many reasons. The novel grew very quickly, and satire (writing that makes fun of things to show their flaws) became very popular. Plays changed from being about politics to focusing more on strong emotions. Poetry started to explore personal feelings. In thinking, people began to focus on empiricism, which means learning from experience. In economics, ideas about capitalism and trade became very strong.

The name "Augustan" comes from the idea that this time was like the age of Augustus, a Roman emperor known for supporting arts and literature. Writers of this period often used clever, ironic language to hide sharp criticisms.

Contents

Historical Context

Alexander Pope, a famous poet, wrote a poem called Epistle to Augustus. This poem was actually for George II of Great Britain. It suggested that his time was like the Roman Augustan age, where poetry became more political and satirical. Later, other thinkers like Voltaire also used the term "Augustan" for the literature of the 1720s and 1730s.

Outside of poetry, this period is also called the Age of Reason. This is because people started to use reason and logic more to understand the world. They moved away from old traditions and focused on clear, rational ways of thinking.

One big change in the 18th century was that printed materials became much easier to find. Books became cheaper, and people could buy used books at fairs. Small, inexpensive books called chapbooks and broadsheets spread news and trends from London across the country. New magazines like The Gentleman's Magazine also started. This meant people in different parts of the country knew more about what was happening everywhere else.

Before copyright laws, it was common for people to make copies of books without permission. This helped spread books even faster. Also, a law that controlled printing presses ended in 1693. This allowed printing presses to open in more towns, not just London. This meant the government had less control over what was printed.

All kinds of writing spread quickly. Newspapers started and grew in number. However, these newspapers were often influenced by political groups. Politicians would create their own papers, plant stories, and even pay journalists. Religious leaders also printed their sermons, which sold well. This spread different religious ideas and helped people think more openly.

Magazines were very popular, and essay writing was at its peak. News from the Royal Society (a group for science) was published regularly. People also made "keys" and "digests" of scholarly books. These summaries helped explain complex ideas to a wider audience. Books on manners, letter writing, and morals also became common. Even economics started as a serious subject, with many ideas for solving problems in England, Ireland, and Scotland.

This explosion of information meant that more people in the 18th century were educated than ever before. Education was not just for the rich. Anyone who could read and get books could learn. It was an "age of enlightenment" because people really wanted logical explanations for nature and humans. It was an "age of reason" because clear, rational methods were seen as better than old traditions. However, this also meant that false information and strange ideas could spread more easily. It became harder to trust everything you read, just like it can be on the internet today.

Political and Religious Context

The period before this, called the Restoration, ended with big changes in how England was ruled. Parliament decided that only Protestant rulers could be on the throne. This brought William III and Mary II to power instead of James II. Later, Queen Anne became queen. Her reign saw two wars and great victories by John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough.

During this time, political parties, the Whigs and Tories, fought fiercely. They believed that real power was with the leading ministers. This led to the rise of the prime minister position, with Robert Walpole becoming very powerful. When Queen Anne died without children, George I from Hanover became king. He didn't speak much English, which meant Parliament gained more power. His son, George II, spoke more English, but Parliament's power continued to grow.

London's population grew a lot during this time. Many people from the countryside moved to London looking for work because farming was changing. This led to more poor people and more crime in the city. Writers often wrote about these fears of crime and poverty.

New, inexpensive drinks became popular, and some people worried about their effects. Religious groups who were not part of the official Church of England also grew. They often preached to the poor in the city. While Queen Anne favored the traditional church, King George I and II were more open to other Protestant groups. They were also worried about supporters of the old Stuart royal family, who wanted to take back the throne.

History and Literature

Literature in the early 18th century was very political. Writers of poems, novels, and plays were often involved in politics or funded by political groups. They didn't try to be separate from the world. Instead, they wrote about the problems and wrongdoings of their time.

Satire was the most popular type of writing. It appeared in prose, plays, and poetry. These satires sometimes gently made fun of human flaws. But often, they were sharp criticisms of specific policies, actions, and people. Even works that seemed general often had hidden political messages.

Because of this, to understand 18th-century literature, you need to know about the history of the time. Writers were writing for people who knew what was happening. They were often responding to or commenting on other writers. For example, novels were written against other novels, and plays made fun of other plays. So, history and literature were closely connected. Writers were trying to figure out new ways of government, new technologies, and new challenges to old ideas about philosophy and religion.

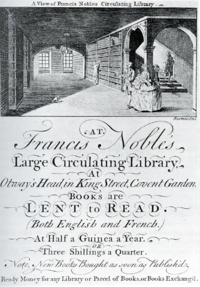

Prose

The essay, satire, and dialogue (in philosophy and religion) were very popular. The English novel also truly began as a serious art form. More people from all social classes learned to read. Libraries where people could borrow books, called circulating libraries, started in England during this period. These libraries were open to everyone, but they were especially popular with women and for reading novels.

Essays and Journalism

English essayists developed their own style. Magazines and newspapers grew between 1692 and 1712. They were cheap to make, quick to read, and a good way to influence public opinion. Many were run by a single writer with help from others.

One magazine, The Spectator, was more popular than all others. It was written by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele. They created fictional characters, like "Mr. Spectator," to comment on manners and events. This calm, observing viewpoint was important for the English essay. Samuel Johnson also wrote over 200 essays, sharing his wisdom about human flaws and moral strength.

After The Spectator became successful, more political magazines appeared. Political groups quickly realized how powerful these publications were. They started funding newspapers to spread rumors and support their views. Politicians wrote for papers, and some magazines were known to be mouthpieces for certain parties.

Dictionaries and Lexicons

The 18th century was a time of great progress in many areas. However, the English language was becoming a bit messy. A group of London booksellers asked the famous essayist Samuel Johnson to create rules for the English language.

After nine years, the first edition of A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755. Johnson's deep knowledge of words and literature made his dictionary special. Each word was defined in detail, with examples of its different uses and many quotes from famous writers. This was the first dictionary of its kind, with 40,000 words and nearly 114,000 quotes.

Johnson's Dictionary was very well received. People enjoyed reading it because the definitions were witty and thoughtful. They were supported by passages from beloved poets and philosophers. Johnson's way of organizing and presenting the dictionary greatly influenced how future English dictionaries were made.

Philosophy and Religious Writing

The Augustan period had less religious conflict in its literature than the previous era. However, Daniel Defoe, a famous writer often linked with the novel, was also a prominent Puritan writer. After Queen Anne became queen, Protestants who disagreed with the official church became less aggressive in their writings. Defoe's famous satirical work, The Shortest Way with the Dissenters, made fun of the worries of the official church about these dissenting groups.

Later, one of the most important religious works of the time was William Law's A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728). Both Law and Robert Boyle (whose Meditations were also popular) called for a revival of religious feeling. Their works focused on the individual's spiritual journey, not just the community's.

Unlike the previous century, where John Locke dominated philosophy, the 18th century saw many thinkers building on Locke's ideas. Bishop Berkeley argued that things only exist if they are perceived. He believed that God perceives things humans don't, which explains why things continue to exist. So, for Berkeley, doubt leads to faith.

David Hume, on the other hand, took doubt to its extreme. He questioned many assumptions, even those that other thinkers took for granted. Hume focused on what could be proven and experienced. His ideas later influenced utilitarianism, which focuses on actions that bring the greatest good to the greatest number of people.

In social and political thinking, economics became very important. Bernard de Mandeville's The Fable of the Bees (1714) caused a lot of discussion about trade and morals. Mandeville argued that things like wastefulness and pride, which seem like "private vices," could actually be good for society. This is because they made people spend money and employ others, helping the economy. Mandeville's ideas were often quoted by economists who wanted to separate trade from moral questions.

After 1750

Adam Smith is known as the father of capitalism. His book Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) explored new ideas about moral behavior. He emphasized "sympathy" between people as the basis for good actions. These ideas influenced the sentimental novel and even the early Methodist movement.

Smith's most famous work was An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Like other thinkers of his time, he looked at the history of trade without focusing on morals. Instead of starting with ideal morals, he examined real-world situations to find rules about how economies work.

The Novel

Newspapers, plays, and satires helped set the stage for the novel. Long prose satires, like Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726), had a main character who went on adventures and learned lessons. The Spanish novel Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605, 1615) was also a very important influence. These three types of writing—drama, journalism, and satire—blended to create different kinds of novels.

Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719) was the first major novel of the century. Defoe was a journalist, and he heard about a real person, Alexander Selkirk, who was stranded on an island. Defoe used parts of this true story to create his fictional tale. In the 1720s, Defoe also interviewed famous criminals and wrote about their lives. From this, he might have gotten the idea for Moll Flanders (1722), a story about a woman's life.

Defoe's works often had a Puritan theme. They usually involved a character falling into trouble, experiencing a spiritual change, and then rising again, wiser than before. This structure meant that each character had to learn important lessons about themselves.

After 1740: Sentimental Novel

The sentimental novel became popular after 1740. Famous examples include Samuel Richardson's Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740) and Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy (1759–67).

Samuel Richardson's Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740) was a major step forward for the English novel. Pamela Andrews is a young servant girl who writes letters to her mother. The novel ends with her marrying her employer, Mr. B, and becoming a lady. Pamela showed the rise of different social classes. The book quickly led to many satires, like Henry Fielding's Shamela (1742). Fielding also wrote Joseph Andrews (1742), about Pamela's brother. Fielding believed in "good nature," an inner goodness that can overcome social class.

From 1747 to 1748, Samuel Richardson published Clarissa. This novel is a sad story about a young girl forced into a marriage she doesn't want. She falls into the hands of a tricky man named Lovelace and eventually dies. It's a masterpiece of psychological realism and emotion. Even Henry Fielding, who had satirized Richardson, begged him not to kill Clarissa.

Fielding's Tom Jones (1749) offered a different view. It also explored whether a person can choose their own partner. But it emphasized how family and society affect individual choices.

Two other important novelists were Laurence Sterne and Tobias Smollett. Sterne's Tristram Shandy (1759–1767) was a very unusual autobiography. The narrator tries to write his life story but keeps going backward in time to explain things. It's full of humor, digressions, and parodies.

Tobias Smollett, a journalist and historian, wrote more traditional novels. He focused on picaresque stories, where a character from a lower class goes on many adventures. Smollett's novels were known for their detailed descriptions of everyday life. In the 19th century, many novelists would follow Smollett's style of long, linear plots.

Many women also wrote novels during this time. They moved away from old romance stories. Examples include Sarah Scott's utopian novel Millennium Hall (1762) and Frances Burney's autobiographical works. These novels showed diverse stories and styles.

Satire

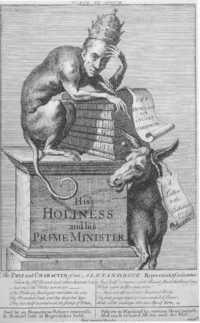

The Augustan era is famous for its excellent satirical writing. Masterpieces include Swift's Gulliver's Travels and A Modest Proposal, Pope's Dunciads, and Fielding's Shamela. Many other satirical works were written, though they are less known today. A group of writers called the "Scriblerians"—Pope, Swift, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot—shared similar goals in their satire.

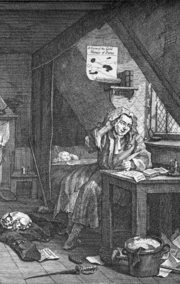

Many experts believe that Jonathan Swift was the most important prose satirist of the 18th century. Swift wrote both poetry and prose, and his satires covered many topics. Swift was especially good at combining parody (imitating someone's style to make fun of them) with satire. He would pretend to be an opponent and imitate their writing style, making the parody itself the satire.

Swift's first major satire was A Tale of a Tub (1703–1705). It talked about the difference between "ancients" and "moderns." "Moderns" valued trade, science, and individual reason. "Ancients" believed in old traditions and society over individual ideas. Swift's satire made the "moderns" seem foolish and proud of their foolishness.

Swift's most important satire is Gulliver's Travels (1726). It mixes autobiography, allegory, and philosophy. The main theme is a critique of human pride. Gulliver travels to different lands, each showing a different aspect of humanity. For example, in the land of the Houyhnhnms, horses ruled by pure reason, humans are shown as dirty, animal-like creatures. Swift suggests that even too much reason can be bad, and humans need to find a balance.

Other satirists were less harsh. Tom Brown, Ned Ward, and Tom D'Urfey wrote humorous satires in prose and poetry. Tom Brown's Amusements Serious and Comical (1700) and Ned Ward's The London Spy (1704–1706) offered entertainment rather than specific political attacks.

After Swift's success, parodic satire became very popular. The political situation, especially Robert Walpole's strong influence in Parliament, led to a lot of political writing and satire. Parodic satire was a good way to criticize policies without offering new solutions. It was ideal for those who wanted to point out flaws in current changes. Satire was everywhere in the Augustan period, in all forms of writing. It was so common and powerful that some literary historians call this time the "Age of Satire."

Poetry

In the Augustan era, poets often wrote in response to each other, using satire when they disagreed. There was a big debate about the role of pastoral poetry (poems about shepherds and country life). This reflected two ideas: the growing importance of the individual's feelings and the idea that art should be a public performance for society's benefit.

Poetry forms gradually changed. Odes stopped being just praises, and ballads stopped being only stories. Elegies became less about sincere memorials. Satires became less specific, and lyric poems started to celebrate the individual rather than just a lover's complaints. These changes might be linked to the rise of Protestantism or the growing power of the middle class. Whatever the reason, there was a clear split between those who supported a social view of people and those who championed the individual.

Alexander Pope was the most important poet of the Augustan age. Many of his lines became common sayings. Pope had few poetic rivals but many personal enemies, and he often argued in print. Pope and his enemies (whom he called "the Dunces") debated what poetry should be about and how a poet should sound.

The debate about pastoral poetry was significant. After Pope published his Pastorals in 1709, a review praised Ambrose Philips's pastorals over Pope's. Pope responded with a sarcastic praise of Philips's poems, pointing out their weaknesses. Pope believed that pastoral poems should show an ideal, "Golden Age" version of shepherds, not how they really were. Philips, however, wanted to "update" the pastoral. Both poets were changing the traditional form, but in different ways.

Pope's friend John Gay also adapted the pastoral. He wrote a parody called The Shepherd's Week. He also imitated the Roman satirist Juvenal in his poem Trivia. In 1728, his play The Beggar's Opera was a huge success. These works often showed compassion. In Trivia, Gay writes as if he feels for Londoners dealing with city dangers. The Shepherd's Week shows the funny parts of everyday life. Even The Beggar's Opera, which satirizes Robert Walpole, shows its villains with some sympathy.

Throughout the Augustan era, it was common to "update" Classical poets. These were not direct translations but "imitations." This allowed poets to express critical ideas without taking full responsibility. For example, Alexander Pope could criticize the King by "imitating" Horace in his Epistle to Augustus. Similarly, Samuel Johnson wrote London, an "imitation of Juvenal," to complain about the political situation. These imitations were conservative in that they valued classical education, but they were used for progressive political purposes.

Pope wrote his most famous attack on his enemies in The Dunciad. The poem tells the story of the goddess Dulness choosing a new leader. She picks one of Pope's enemies, Lewis Theobald, and the poem describes his coronation and games held by all the "dunces" (fools) of Great Britain. When his enemies responded, Pope added more "learned" commentary to his poem. In 1743, he added a fourth book and changed the hero to Colley Cibber. In this new book, Pope suggested that darkness and foolishness would eventually win over light and knowledge.

John Gay and Alexander Pope represented different ideas. The Dunciad attacked figures Pope saw as dangerous and "antisocial" in literature. They were vain and greedy, caring nothing for morals. Gay also wrote about social dangers and follies that needed to be fixed for the good of society. His characters often represented society as a whole.

On the other side were poets who agreed with the politics of Gay and Pope but had a different approach. These included James Thomson and Edward Young.

Precursors of Romanticism

In 1726, two poems appeared that described landscapes from a personal viewpoint. They drew feelings and moral lessons from direct observation. These were John Dyer's "Grongar Hill" and James Thomson's "Winter" (part of The Seasons). Unlike Pope's ideal pastoral, these poems had little mythology and didn't celebrate Britain or the crown. Dyer's poem celebrated natural beauty, while Thomson's was melancholic. This sadness became a proper emotion for poetry.

A notable successor was Edward Young's Night Thoughts (1742–1744). This poem was even more about deep solitude, melancholy, and despair. These poems show the beginnings of the Romantic style: celebrating the private individual's unique feelings about the world.

These ideas about the solitary poet were further developed by Thomas Gray. His Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard (1750) started a new trend for poetry about sad reflection. It was set in the "country," not London. The poem suggests that only by being alone can the poet speak a truth that is truly personal. After Gray, a group called the Churchyard Poets imitated his style. Other conservative poets like Oliver Goldsmith (The Deserted Village) also adopted this new poetry of solitude and loss.

When the Romantics appeared later in the 18th century, they were not inventing the idea of the individual self from scratch. They were just formalizing what had already begun. Also, the late 18th century saw a revival of old ballads, with Thomas Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Many of these ballads were not very old, but this movement helped create an interest in folk culture. When this folk-inspired idea combined with the individualistic ideas of the Churchyard Poets, Romanticism became almost certain.

Drama

The Augustan era in drama ended clearly in 1737 with the Licensing Act. Before 1737, English plays were changing quickly. They moved away from the Restoration comedy and Restoration drama (which focused on noble characters) towards melodrama (plays with strong emotions and clear good/evil characters).

George Lillo and Richard Steele wrote influential plays in the early Augustan period. Lillo's plays focused on everyday people like shopkeepers and apprentices, not kings. They showed drama on a family scale, not a national one. The problems in his tragedies were common flaws like giving in to temptation. The plays ended with Christian forgiveness. Steele's The Conscious Lovers (1722) was about a young hero avoiding a duel. These plays set new values for the stage. They aimed to teach and inspire the audience, not just amuse them. They were popular because they seemed to reflect the audience's own lives.

Joseph Addison also wrote a play called Cato in 1713. It was about the Roman statesman Cato the Younger. This play was important because Queen Anne was very ill, and people were worried about who would be the next ruler. Both the ruling Tory party and the opposition Whig party saw Cato as a symbol of integrity. Both sides cheered the play, even though Addison was a Whig.

Just like during the Restoration, money influenced the stage in the Augustan period. Before, royal support meant success. But after William and Mary, the royal court lost interest in plays. Theaters had to earn money from city audiences. So, plays that showed city worries and celebrated the lives of ordinary citizens became popular.

This led to many plays that were not very literary but were staged often. Theater managers like John Rich and Colley Cibber competed with special effects. They put on plays that were mostly spectacles, with the text being less important. Dragons, whirlwinds, thunder, ocean waves, and even real elephants appeared on stage. Battles and explosions were common. Rich was famous for his pantomimes. These plays are not often studied today, but they made established writers very angry.

Also, opera came to England during this time. Opera combined singing and acting, which went against the strict rules of neoclassicism. Satirists saw opera as something very bad. Pope wrote in Dunciad B:

- "Joy to Chaos! let Division reign:

- Chromatic tortures soon shall drive them [the muses] hence,

- Break all their nerves, and fritter all their sense:

- One Trill shall harmonize joy, grief, and rage,

- Wake the dull Church, and lull the ranting Stage;

- To the same notes thy sons shall hum, or snore,

- And all thy yawning daughters cry, encore." (IV 55–60)

John Gay made fun of opera with his satirical Beggar's Opera (1728). It also parodied Robert Walpole's actions during the South Sea Bubble (a financial crisis). The play was a huge hit. However, when Gay wrote a sequel called Polly, Walpole had the play banned before it could be performed.

Playwrights faced difficulties. Theaters were putting on pantomimes instead of well-written plays. And if a satirical play appeared, the government would ban it. Henry Fielding took on Walpole. His play Tom Thumb (1730) made fun of all the tragedies written before it. It was also an attack on Robert Walpole, who was sometimes called "the Great Man." In the play, the "Great Man" is a tiny midget, showing his flaws. Walpole responded, and Fielding's revised play was only printed, not performed.

A play of unknown authorship called A Vision of the Golden Rump was mentioned when Parliament passed the Licensing Act of 1737. This Act required all plays to be approved by a censor before they could be performed. The first play banned was Gustavus Vasa by Henry Brooke. Samuel Johnson wrote a satirical piece making fun of the censors.

The Licensing Act made people suspicious of any play that was approved. So, theaters had to perform old plays or pantomimes with no political content. This meant that William Shakespeare's plays became much more popular. Sentimental comedies and melodramas were also the main choices.

Later in the 18th century, Oliver Goldsmith tried to bring back satirical comedy with She Stoops to Conquer (1773). Richard Brinsley Sheridan also wrote several satirical plays after Robert Walpole's death.

See also

- Augustan drama

- Augustan poetry

- Augustan prose

- Jonathan Wild

- The Mint

- Novel

- Restoration literature

- Romantic poetry

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |