Civil Directory of Primo de Rivera facts for kids

The Civil Directory was the second and final part of Primo de Rivera's rule in Spain. It started in December 1925, replacing the Military Directory that had been in charge since his takeover in September 1923. Primo de Rivera wanted to make his government more stable by getting support from civilians. However, his plan didn't work. He resigned in January 1930, and King Alfonso XIII also stopped supporting him. This led to a new government called Berenguer's "dictatorship".

Contents

How the Civil Directory Started

After the parliament was closed in November 1923, Primo de Rivera decided his rule would not be short. By April 1925, he was already thinking about a new government. This would happen once the war in Morocco was settled.

After the successful Alhucemas landing, Primo de Rivera decided to create the Civil Directory. This success made him very popular. It allowed him to move the army back to their barracks. He wanted to start a more civilian phase of his government.

On December 3, 1925, Primo de Rivera formed his first civilian government. But important jobs like President, Vice-President, Interior, and War were still held by military officers. He made it clear that the Constitution would remain suspended. He also said there would be no elections. His goal for the new Civil Directory was to improve the economy. He also wanted to prepare new laws. These laws would help Spain return to normal political life later.

The Civil Directory brought back the Council of Ministers. It had traditional government roles. The group was half civilian and half military. The civilians were part of the Patriotic Union. Important civilian ministers included José Calvo Sotelo in Finance and Count of Guadalhorce in Public Works. José Yanguas Messía was also a key minister in the State department. However, Primo de Rivera only discussed big political decisions with General Severiano Martínez Anido.

With the Civil Directory, Primo de Rivera showed he wanted to stay in power. He did not set a clear date for ending his rule.

Trying to Make the Regime Permanent

The first step to make his government permanent was creating the "single party," the Unión Patriótica, in April 1924. The second step was forming the Civil Directory. Next, he set up the National Corporate Organization. He also called for the National Consultative Assembly. This assembly was supposed to write a new Constitution.

Calling the National Consultative Assembly in September 1927 was a big change. It showed the dictatorship was moving away from the old parliamentary system. The Patriotic Union rejected the ideas of the 1876 Constitution. Instead, they wanted a system based on corporations. This meant they were against traditional politics and parliaments. They also wanted a strong central government.

The National Corporate Organization (OCN)

The dictatorship tried to find a middle ground for workers' groups. It was between free unions and the single, required unions of totalitarianism. Primo de Rivera wanted to replace traditional class unions. He aimed to create "unions" that focused on welfare, education, and rules for their members. These unions would also help choose worker representatives. These representatives would work in joint committees for different jobs. Primo de Rivera clearly stated his goal: workers' groups should focus on culture and protection, not on fighting with employers.

The National Corporate Organization (OCN) was created in November 1926. Its main goal was to keep peace in society. It did this by getting involved in labor issues. The OCN had three levels. The first level had joint committees. The second had provincial Mixed Commissions. The highest level was the corporation councils for each trade. Employers and workers had equal representation at each level. The local Joint Committees were very important. They were meant to manage the rules for each profession.

Primo de Rivera invited the socialist union, the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), to join the OCN. This caused a big split within the UGT. Some, like Francisco Largo Caballero, wanted to work with the dictatorship. Others, led by Indalecio Prieto, were against it. Those who wanted to collaborate won. The UGT joined the OCN. They said it didn't stop the right to strike. They also liked that worker representatives were chosen democratically. The UGT held about 60% of the worker representation in the OCN. Their membership grew slightly during this time.

The Joint Committees helped reduce labor conflicts. But in the last two years of the dictatorship, strikes started again as the economy worsened. The government responded with force. Even UGT centers were closed.

Employers and the Free Trade Unions began to criticize the OCN from 1928. They called it too "state-controlled." By the end of the year, employer groups openly opposed it. They wanted the Joint Committees to be dissolved or only handle disagreements. This meant the OCN lost the support of conservative groups. They saw Primo de Rivera's policies as a threat to their interests.

The Patriotic Union

In July 1926, the National Assembly of Patriotic Unions met in Madrid. They approved the party's rules. They also elected members for the party's leadership. Primo de Rivera was confirmed as the National Chief. A National Board of Directors was appointed. This board was like the Grand Council of Fascism. However, it only met once after the assembly. At the local level, civil governors controlled the Patriotic Union. They appointed the local leaders.

In February 1927, Primo de Rivera ordered civil governors to appoint Patriotic Union members to city councils. This was viewed with suspicion by some of his own ministers. They noticed that many old politicians were joining the Patriotic Union. They just wanted to stay in power.

The Patriotic Union reached its highest number of members in July 1927. Official figures showed over 1.3 million members. But this number dropped significantly by late 1929. This showed that many Spanish people were not very excited about Primo de Rivera's movement. The party's newspaper, La Nación, also had low circulation.

The Patriotic Union became a tool for the government's propaganda. It always followed the orders of its chief. For example, it organized a large demonstration in Madrid in September 1928 to support the regime. In February 1929, Primo de Rivera also made it a kind of police helper. It was given tasks to investigate and gather information. It worked with the Somatén, forming a "patriotic league." When the new Constitution draft was rejected in July 1929, the Patriotic Union campaigned to defend it. They attacked the 1876 Constitution. A big rally was held in Madrid in September 1929.

Mobilizing the People

The dictatorship was the first in Spain to use mass propaganda. It tried to bring people together for the nation. The government understood that guiding the demands of the people was key to its survival. But this wasn't like the mass rallies of fascism. Traditional groups like the Church and the Army were always present. They promoted traditional, religious values. However, there was also a desire to create a "new man." This new person would be hardworking, moral, and healthy. The regime tried to teach these values in military barracks, churches, and schools.

Mass mobilization involved large "patriotic" demonstrations. These were organized by the Patriotic Union and the government. For example, in 1924, a rally was held in Madrid. It was a response to a book criticizing the dictatorship and the King. Primo de Rivera received an album with millions of signatures of support. Half a million medals honoring the King were given out.

One of the most important demonstrations was on September 13, 1928. This was the fifth anniversary of Primo de Rivera's takeover. The dictator wanted to show what the Patriotic Union was. He wanted people to compare the "embarrassing" old system with the "satisfactory" new one. There were parades and demonstrations across Spain. On September 13, groups from different provinces paraded in Madrid. They wore traditional costumes and had music. Primo de Rivera watched from a special stand. A large rally followed in the Plaza de Oriente, with about 100,000 people. Airplanes flew overhead.

Other tools for teaching people were "patriotic" ceremonies. These were organized by military government officials. They happened on special days like the Fiesta de la Raza. They also included events honoring troops and flag swearings. "Patriotic" talks were also given. These talks promoted Spanish virtues and traditions. They also stressed defending the homeland and respecting authority. These talks were meant to "sow moral and patriotic ideas" among peasants. For children, a "Catechism of the Citizen" was published. It aimed to improve the race and give young people patriotic education. It wanted to create new generations with strong morals and bodies.

To prepare young people for military service, the National Service of Physical, Civic and Pre-military Education (SNEFCP) was created in January 1929. Its goal was to make society more like the military. It wanted to create a "new citizen" with military values. It also aimed to "improve the race." The SNEFCP taught civic duties and pre-military training to young people aged 19 and older. Army commanders led these programs. They also gave patriotic talks.

Physical education followed Army rules. It included games and sports. Military training focused on using terrain for combat and shooting. Those who passed tests got special benefits in military service. The goal of "moral education" was to make young people proud of being Spanish.

Local governments were asked to provide places for the SNEFCP. But many mayors said they didn't have enough money. So, the dictatorship changed the plan. Military chiefs became "inspectors" for teachers. These teachers then handled physical and pre-military education. The SNEFCP stopped in January 1931, after the fall of the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. The Second Spanish Republic later ended it completely.

The 1929 Draft Constitution

When drafting the new Constitution, there were two main ideas. Some, like Juan de la Cierva, wanted to keep parts of the 1876 Constitution. Others, like Ramiro de Maeztu, wanted a completely new one. They believed that rights should be limited. José María Pemán, a key thinker of the dictatorship, supported a new Constitution.

Primo de Rivera also wanted a new Constitution. He believed it should be based on the "sovereignty of the State." This idea came from fascism. It was different from the liberal idea of national sovereignty. He also saw the Army as the "arm of the State," above the government. The new government would have only one chamber. Its members would be chosen by corporate suffrage. The Patriotic Union would be the only party.

The idea for a completely new Constitution won. The final draft was released on July 5, 1929.

The famous lawyer Mariano Gómez called it a charter granted. He said it broke completely with Spain's past constitutions. Conservatives, liberals, republicans, and socialists all rejected it. Even the National Consultative Assembly criticized it.

In the end, no one was happy with the draft. Not even Primo de Rivera. He thought it gave too much power to the King. On September 13, 1929, Primo de Rivera shared his concerns. He pointed out the "imbalance of powers" favoring the Crown.

So, the new Constitution plan quickly stalled. The political discussion then shifted to creating a truly new constitution. The dictatorship failed because it couldn't find a new way to govern. This, along with other problems and a money crisis, led to the regime's collapse.

Policies of the Civil Directory

Education

The Civil Directory continued the education policies of the Military Directory. These policies had two main goals. First, they wanted to lower the high rate of illiteracy. Second, they aimed to make schools more "national." The dictatorship was very successful in reducing illiteracy. The rate dropped from 52.35% in 1920 to 42.33% in 1930. This was possible because the budget for public education increased. Between 1924 and 1930, it was 5.74% of the national budget. This allowed for 8,000 new schools to be built. These schools welcomed 300,000 new students. The number of primary school teachers also grew.

To "nationalize the school," new rules were made. They ensured that Castilian Spanish and Catholic religion were taught. In June 1926, a rule said teachers who didn't teach in Castilian could be suspended or moved. Schools could even be closed. In 1927, attending mass became required for teachers and students.

For high school education, the dictatorship mostly left it to religious schools. It didn't build many public high schools. In August 1926, the Minister of Public Instruction, Eduardo Callejo de la Cuesta, reformed high school studies. More focus was put on science and Spanish history. Religion also became a required subject. The number of high school students grew by 20%. This was due to better economic times for middle-class families.

The number of university students grew a lot. It doubled between 1923 and 1930. In May 1928, a new law reformed university studies. This "Callejo reform" allowed degrees from two private Church-owned universities to be recognized. This caused huge protests from university students. Even when Primo de Rivera removed the article, the protests continued. They lasted until the dictatorship fell in January 1930. They even continued until the monarchy fell in April 1931.

Religious Policy

The dictatorship wanted to strengthen the Catholic Church's influence on society. It supported groups like the League against Immorality. These groups aimed to stop bad behavior and promote Sunday rest. This created a very strict atmosphere. It promoted a "good citizen" who was patriotic, Catholic, and very moral. This was a step towards the national-Catholicism of Franco's later dictatorship. The Church's support for the dictatorship had bad consequences later.

Primo de Rivera had only one conflict with the Catholic Church. This was when Catalan bishops refused to order priests to preach in Spanish. Primo de Rivera wanted to stop the use of the Catalan language, even in church. This made the Catalan clergy become defenders of regional freedoms.

Foreign Policy

After the success in Morocco, Spain's foreign policy became more active. Primo de Rivera wanted Spain to have a permanent seat on the Council of the League of Nations. He also wanted Tangier, a city in Morocco, to be part of the Spanish Protectorate. Mussolini of Italy supported him at first. This made France and Great Britain suspicious. They were also responsible for Tangier's international status. This led to a closer relationship between Fascist Italy and Spain. They signed a friendship treaty in August 1926.

Spain was already a member of the League of Nations Council. But it was elected for temporary seats. Primo de Rivera wanted a permanent seat for prestige. In March 1926, Spain tried to explain its reasons. But it didn't succeed. To force the League to accept, Primo de Rivera brought up the Tangier issue again. He asked for it to be part of Spain's protectorate. France and Great Britain offered to make Spain a permanent member in practice. They would re-elect Spain to temporary seats forever. But Primo de Rivera refused. He threatened to leave the League of Nations. However, he didn't follow through. In March 1928, Spain returned to its activities. It was re-elected to the council in September 1929. Primo de Rivera only managed to have a League of Nations meeting in Madrid. Spain also got to appoint the chief of police in Tangier. But Tangier's international status remained.

These failures made Primo de Rivera change his foreign policy. He focused on Portugal and Latin America. This was helped by a military takeover in Portugal in 1926. The dictatorship supported the flight of the Plus Ultra seaplane. It flew from Spain to Buenos Aires in January 1926. The Ibero-American Exposition of Seville, opened in May 1929, had a similar goal. It aimed to strengthen ties between Spain and American republics. Other examples of this policy were the Cervantes Monument in Madrid and restoring the mausoleum of the Catholic Monarchs.

Primo de Rivera wanted to improve relations with former Spanish colonies in America. He said he wanted to "increase and strengthen the flows of love between Spain and America." He wanted to treat Americans as brothers. This policy focused on cultural and spiritual ties, not just economic ones.

In the end, this focus on Latin America helped distract people from problems in Morocco. It also gave the controlled press something positive to report.

Economic Policy

The dictatorship often talked about its economic successes. But the good international economy of the "Roaring Twenties" played a big part. Primo de Rivera's economic policy involved more government control. For example, new industries needed government permission. It also protected "national production." Two important achievements were creating CAMPSA (a oil monopoly) in June 1927. Also, the Compañía Telefónica Nacional de España (a phone company) was formed. It had mostly American capital.

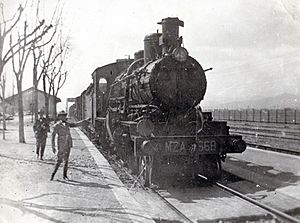

The government's economic involvement was most clear in public works. This included water projects, roads, and railroads. Electricity was also brought to rural areas. However, these policies were not new. Spain had a long history of economic nationalism and government involvement. Primo de Rivera just made them more intense.

To pay for the big increase in public spending, the government didn't raise taxes. Instead, it borrowed money. This led to heavy debt, both foreign and domestic. It also put the peseta (Spain's currency) at risk.

One of the dictatorship's main claims was that it had made the peseta stronger. When Primo de Rivera took power, the dollar was worth 7.50 pesetas. In the following years, the peseta gained value against the dollar and the pound. In 1927, the dollar was 5.18 pesetas. But this was mostly artificial. It was due to foreign money coming in because of high interest rates. This worried exporters, especially in Catalonia. They said a stronger peseta made it harder to sell goods abroad.

In 1928, foreign money started leaving the country. The peseta began to lose value. This was due to doubts about the regime and a large government budget deficit. The Minister of Finance, José Calvo Sotelo, tried to stop the fall. He created a committee to buy pesetas in the London market. But this wasn't enough. Calvo Sotelo even blamed "enemies" of the regime. He then tried to raise interest rates and limit imports. These measures also failed.

In October 1929, the policy of supporting the peseta was stopped. The money used for it was gone, and the peseta kept falling. The next month, they decided to fix the budget deficit. But Calvo Sotelo still refused to devalue the peseta. He thought it was "unpatriotic." He tried to get Spanish banks to lend money, but this failed. Facing these problems, Calvo Sotelo resigned in January 1930. Primo de Rivera resigned just a few days later.

Historians say the dictatorship was a key time for Spain's economy. Industrial production grew a lot. However, some believe that government control and protectionism stopped even greater growth. But these policies were common in Europe between the wars.

Social Policy

In 1924, Primo de Rivera appointed Eduardo Aunós to organize a new system for labor relations. This led to the National Corporate Organization in November 1926. He also introduced many social measures. While some started during the Military Directory, most were adopted during the Civil Directory. In July 1926, subsidies were given to large families of workers and civil servants. Rules for workers' retirement and home work were also set. In December, the Sunday Rest Law was passed. The next year, measures against women working at night were approved. In 1928, wages under 8.5 pesetas were made tax-free. In March 1929, pregnant women were included in welfare insurance. During these years, the number of people receiving workers' pensions tripled. This was thanks to a big increase in funds for social welfare.

The Fall of the Dictatorship

Groups that first supported the dictatorship slowly stopped. Regional groups were unhappy because the dictatorship didn't keep its promise to give them more power. Business groups didn't like the UGT getting involved in their companies. Intellectuals and universities were disappointed. Liberal groups saw that the dictatorship wanted to stay in power forever. The King also started to worry that his own position was at risk if he kept supporting the dictator.

There were two attempts to overthrow Primo de Rivera and bring back the old system. The first was called the Sanjuanada in June 1926. The second happened in January 1929 in Valencia. Its main leader was José Sánchez Guerra. Artillery officers were also involved. Between these two attempts, there was the Prats de Molló plot. This was an attempt to invade Spain from France. It was led by Francesc Macià and his party Estat Catalá, with help from anarcho-syndicalist groups.

As the dictatorship lost support, opposition groups grew. Some old politicians, like José Sánchez Guerra, openly opposed the dictatorship. He went into exile and later joined the January 1929 coup attempt. Other politicians, like Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Miguel Maura Gamazo, joined the Republican side. They formed the Liberal Republican Right. Republicans also grew stronger with Manuel Azaña's new group. They formed the "Republican Alliance" in February 1926.

Primo de Rivera was losing support from society and politicians. His health was also getting worse. He tried to get more support from the Army, which was another key part of his power. But the Army's response was not strong enough. So, he resigned to the King on January 28, 1930. The King accepted immediately. Alfonso XIII then appointed General Dámaso Berenguer to lead the government. The goal was to return to a normal constitutional system.

See also

In Spanish: Directorio civil de Primo de Rivera para niños

In Spanish: Directorio civil de Primo de Rivera para niños